Middle East Update: Iran expands Middle East influence into Caspian Sea

Iran's strategic position between the Persian Gulf, Caspian Sea, and the Indian subcontinent continues to play a pivotal role in securing oil and natural gas export outlets for Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to outside markets.

As synergies among these Caspian Sea countries develop into closer working relationships, the politically charged issue of where to place regional petroleum export routes will soon come to closure as economic drivers decide the final outcome.

Much of the recent activity involving Iran and Caspian hydrocarbon exports has focused on swap arrangements between countries.

Meanwhile, the focus on Caspian pipeline exports is beginning to shift from oil to gas with a push to transport Turkmen gas to Turkey via pipe line.

Looming over these developments is the continuing debate over US sanctions targeting Iran and how promising signs indicate US companies may yet be allowed to return to that country.

Iran oil swaps

In January, the first of several anticipated "oil swap" pipelines came into play as Iran finished linking up a new line at the south Caspian Sea port of Neka with its refinery at Rey, located south of Tehran (Fig. 1).

Because of Iran's large resource base, extensive pipeline network, and large-scale refining capacity (Tables 1-3), the country now has the necessary infrastructure to:

- Swap Caspian crude for equivalent quantities at Persian Gulf ports.

- Transport Caspian crude directly onward "as is" to southern ports.

- Transport Caspian crude to Iranian refineries and use the resulting products internally.

- Transport Caspian crude to Iranian refineries and ship those products to outside markets.

"The Iran option offers a much lower cost as compared with existing routes to the Black Sea and especially those proposed to the Mediterranean," said Brooks Frazier, president of Caspian Steppes, a Houston consultancy focused on Caspian energy issues. "While presenting a major challenge to US policy, these lower rates are extremely attractive to Caspian producers."

Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan are pursuing oil swap arrangements because they provide economic alternatives to pipeline proposals such as the Baku-Ceyhan and TransCaspian routes (promoted by the administration of former President Bill Clinton) that shaves off hundreds of miles in transit for Caspian exporters.

In addition, this transport route allows those countries' state oil firms to bypass restrictions imposed by the US Iran and Libya Sanctions Act of 1996 (ILSA), which targets foreign companies with mandatory or discretionary sanctions if investments exceed $20 million annually.

The Iran oil swap arrangement, however, sidesteps this restriction, because such deals involve the direct purchase of oil at Caspian Sea ports and does not involve capital investments from non-US companies.

Neka-Rey

According to Wood Mackenzie, infrastructure development to support a swap capacity of 350,000 b/d was $360 million, of which $240 million was targeted for construction of 243 miles of 32-in. pipeline and three pumping stations. A further $120 million is required for modifications to the refineries and for storage and blending facilities at Neka.

As of mid-February, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan supplied the Neka-Rey Oil Swap line with about 50,000 bo/d from the ports of Turkmenbashy and Aqtau. As the frequency of shipments increases, with future contributions from Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and possibly Azerbaijan, Iran says that this swap line will soon handle 315,000 b/d, to be increased to more than 425,000 b/d if the existing pipeline between Neka and Rey is upgraded.1

Furthermore, Iran may expand the oil swap network to 700,000 b/d by the addition of three new routes.

The first such route, which begins at the port of Anzali located on the southwestern coast of the Caspian Sea, would require construction of a 100 mile trunk line to the Tabriz and Rey pipelines. By some estimates, this line could feed Rey with 100,000 b/d while providing a similar amount to Tabriz. The second route would entail a similar line but begin at the Port of Noshahr, located due north of Tehran. The third option considers the conversion of a Soviet-era gas pipeline from Astara, located on the coast at the Azerbaijan border, to the Tabriz refinery.

Turkmenistan swaps

Iran has already conducted several pilot runs with the oil swap concept, using various combinations of sea transport, rail, and an existing pipeline between Neka and Rey.

In 1995, Bridas Corp. became the first foreign operator in Turkmenistan to agree to a swap deal with Iran. "But due to nonrelated legal wrangling, Turkmenistan suspended this export license," Frazier said.

In 1998, Monument Resources Petroleum Co. (now Lasmo Oil PLC) began to swap 4,000 b/d from its Burun field in Turkmenistan to the port of Neka. This is expected to increase to 70,000 b/d by 2005. "Such swaps were cheaper as compared with rail," Frazier noted. "Furthermore, the crude is being refined and consumed inside Iran, clearly demonstrating the option for the seller to access refineries close to the source."

In that same year, Dragon Oil PLC also began shipping 6,000 b/d to Iran from its Turkmenistan Cheleken operation in accordance with a 10-year swap arrangement. This volume is expected to rise to 85,000 b/d by early 2001. In 1999, the total amount shipped under this scheme was 1.2 million bbl.

In 1999, Burren Energy PLC also began exporting a portion of its Turkmenistan production from the Nebit Dag area via a swap arrangement with Iran. Finally, Larmag Energy Associates began a 23,000 bbl trial run that was shipped to the port of Noshahr from Cheleken, Turkmenistan.

Kazakhstan swaps

In 1996, Kazakhstan initiated its first swap exchange with Iran by sending shipments from the Aqtau port by marine tankers. Since then, the flow has been limited because of problems associated with contracts and the refining of complex Kazakhstan crudes. Initially, Iranian refineries could not process this crude due to high sulfur, mercaptans, and salt content levels, which has hindered the more-aggressive swap arrangements.

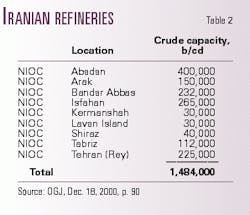

Currently, refineries at Rey and Tabriz are completing upgrades to their treatment facilities. After this work is finished, the Tabriz and Rey refineries could potentially handle 337,000 b/d of Kazakh crude, assuming current operating capacities (Table 2).

The Isfahan and Arak refineries may also be upgraded to handle these crudes with additional processing capacity. "The plan would be to feed the Rey refinery to maximum capacity before diverting to Tabriz, Isfahan, and Arak," Frazier said.

By agreement, the two countries plan to swap up to 20,000 b/d as soon as possible, then steadily increase volumes to 120,000 b/d by 2006. To reach this level, Kazakhstan will probably need to build a pipeline and has assigned some western oil companies to research this option.

Much of this volume would be consumed locally with the rest swapped in equal amounts throughout the Persian Gulf. "By being able to handle such volumes, Iran is demonstrating to Kazakh stan and others that no other export line is needed," Frazier said.

Clearly, Iran is targeting crude oil from the newly discovered Kashagan field in the northern Caspian Sea, perhaps one of the largest discoveries in recent times. TotalFinaElf SA, which recently announced its desire to become the operator at Kashagan, is openly in favor of utilizing Iranian routes.

Reuters news service quoted Reza Majedi, director of National Iranian Oil Co., as saying that crude deliveries from Kazakhstan and Turkmenstan would reach 60,000 b/d by midyear.

He pointed out that "some technical problems concerning the pour point of the Kazakh oil had prevented the swaps from starting already," but he added that those problems would be sorted out soon.2

Ports

The most important Iranian swap ports on the Caspian, from west to east, include those at Anzali, Noshahr, Gaz, and Torkeman near Turkmenistan.

"So far, the eastern ports have been the most important to the swap arrangments," Frazier said. In addition, Iran is building two new ports near Neka-the Amir Abadport and Fereydoon Kenarto-to provide improved oil unloading facilities for barge and tanker deliveries.

Anzali is becoming Iran's biggest northern port, as it is part of the important North-South Freight Corridor joining Russia to Iran and India via Astrakhan. Iran is also renovating the port of Noshahr so it can handle oil tankers.

Gas-oil swaps

The swap concept is not limited to crude.

"Ironically, Iran and Turkmenistan are swapping hydrocarbon types," Frazier said. "Eastern Turkmenistan is gas-rich and oil-poor, whereas Northeast Iran needs gas."

Thus, Iran partially pays for natural gas with oil shipped back across the border.

For the time being, Iran requires all of its Turkmenistan gas to be used for domestic consumption in its northern regions.

Under discussion, however, is the possibility of swap-like arrangements for Turkmenistan gas to serve Northeast Iran with possible equal volumes sold into Turkey and beyond.

By 2003, Turkmenistan plans to sell Iran 5 billion cu m/year of gas.

Gas conduit

Because Turkmenistan has no easy access points from which to market its gas reserves, a reasonable route is to transport it across Iran into Turkey, with a potential extension to Europe.

Iran has also discussed building a line across Armenia with potential market entry into Ukraine and Europe. Such an outlets could also bolster Turkmenistan's gas export plans.

"Turkmenistan has already accomplished the first steps of this much-larger scheme by entry into Iran via two gas lines," Frazier said. The first line, Korpedzhe-Kurtkui, began operation in late 1997 and began transporting around 2 billion cu m/year, a volume expected to increase to 12 billion cu m/year by 2006.

The second gas line, Artik-Lotfabad, began operation in December 2000 and targets Iran's northern region. Initial volumes will be 180,000 cu m/day, increasing to 28 million cu m/year by 2004.

"Since Iran is just about to begin their own gas sales into Turkey, they are not allowing Turkmen gas to be included at this time," Frazier says. "Iran is also not willing yet to let Turkmen gas flow direct to customers acting strictly as a conduit." The near-term plan for Turkmenistan gas sales is for Iran to purchase the gas upon entry and then sell it themselves onward.

Another attraction to Turkmenistan is that Iran pays more than Russia for the gas it buys to satisfy sale obligations into Europe. And, eventually, Iran could also ship Turkmen gas to Pakistan and India, thus bypassing war-torn Afghanistan.

Soon, Iran will also provide an outlet to markets for LNG from Turkmenistan. "When you look at the combined leverage of these two gas-producing giants, it is possible to see why they are steadily aligning themselves ever closer on many major issues," Frazier said.

With present market demand and available pipelines, however, Iran and Turkmenistan remain competitors in the near term. "But if sufficient pipelines are built to reach the Turkish and European markets, their combined potential volumes of 20-25 billion cu m will be a powerful price driver."

"Obviously, this growing relationship is affecting the US-promoted TransCaspian Gas Pipeline," designed to carry Turkmenistan gas across the sea to Azerbaijan and then on in to Turkey. "Turkmenistan is not happy with Azerbaijan demands on how to share the pipeline capacity," Frazier noted. "They are also not accepting Azerbaijan claims to Caspian territory and thus seem to prefer bypassing Azerbaijan altogether by going across Iran into western markets."

Gas provider

On another front, Iran will begin affecting the region with its own gas exports. The 1,536-km Iran-Turkey pipeline, for example, is already complete on the Iranian side and has a 25-year deal in place to deliver 228 billion cu m/year. Deliveries are scheduled to begin first quarter of 2001 with an expected throughput of 350 billion cu m/year by 2007.

"This has been a controversial project, as the US has considered imposing ILSA sanctions while urging Turkey to get gas from any country other than Iran," Frazier said. "The US continues to lobby heavily for routes that completely avoid Iran and Russia."

Iran is also building the IGAT-3 gas pipeline north from South Pars field in the Persian Gulf to feed outlets west into Turkey or north to Europe through the Caucasus region. Apart from feeding Armenia, which has been isolated and neglected in most route scenarios, IGAT-3 could allow gas to reach European markets via Georgia-Russia-Ukraine.

"Basically, Armenia wants to reduce dependence on their 1960s-era nuclear plant," Frazier said. "They are trying to make this gas import line a reality by including [OAO] Gazprom, Iran National Gas, National Gas of Greece, Bridas, and Gaz de France."

Iran is also considering plans to build a 56-in., 2,760-km, $5 billion gas pipeline into India through Pakistan. " A key point to Iran's location on the map is proximity to the growing markets in Asia."

Currently, Azerbaijan relies on Russia for its gas supplies. "What is ironic is that Azerbaijan has a tremendous gas source just offshore in the Shah Daniz field, but its current domestic infrastructure is still set up for winter heating using fuel oil." At some stage in the future, Azerbaijan will switch fuel sources. "Iran wants to run gas through IGAT-1 into Azerbaijan through Astara for the near term, until Azerbaijan can fully utilize their own gas," he said.

US sanctions

While Iran continues to forge new relationships with its neighbors, improved US relations may also enter a new era with the election of President George W. Bush and Vice-Pres. Dick Cheney. In turn, US companies may yet gain access to a country that holds reserves totaling 90 billion bbl of oil and 812 tcf of gas.

Since Iranian President Mohammed Khatami came into power in mid-1997, he has announced intentions to improve relations with the West. "Iran is reaching out more assertively to build bonds and friends," said Amir Zamaninia, senior counsel of the Islamic Republic at Eurasia's Caspian Basin Forum last November. "We are determined to join the train of globalization."

Backing these words up with deeds, Khatami has set up several economic free trade zones and has initiated an ambitious program to build a free-market economy, including the privatization of certain petrochemical and upstream entities.

Furthermore, European and Asian companies now profitably work in Iran through buy-back contracts that allow them to take part in the development of this country's tremendous hydrocarbon resources.

From the US side, former President Clinton has made overtures to Iran in the last couple of years by easing sanctions in regards to the import and export of agricultural products, carpets, and caviar. And perhaps as important, the US government has yet to enforce ILSA against non-US companies.

For example, Royal Dutch/Shell continues to develop the Soroush and Nowruz offshore oil fields 50 miles west of Kharg Island under a buy-back contract.

And TotalFinaElf, which replaced Conoco Inc.'s involvement in Sirri A and E oil fields after the latter was forced abrogate a $550-million contract, has not been penalized either. Other companies that have received waivers include Gazprom and Petronas.

Some hope

Recent events, therefore, show some promise that ILSA may be allowed to expire in August. Although no official word has been released from President Bush, it appears that several key members of his staff, including Cheney and Sec. of State Colin Powell favor ILSA's expiration, at least in regards to Iran. When Cheney was CEO of Halliburton, for example, he called for ending Iranian sanctions, calling the policy a "mistake."

President Bush could therefore veto a renewal of ILSA or a similar proposal, especially as Congress remains equally divided. Nevertheless, strong opposition by key congressional leaders, including Senate foreign relations committee Chairman Jesse Helms, may not allow it to lapse without a fight.

Recent press reports of Sinopec's $150 million plans to upgrade the Neka-Rey oil swap facilities have angered some congressional members, as they do not like the idea of the Chinese communist government aiding and abetting a state the US government has branded as supportive of terrorism.

"People are probably more optimistic about ILSA expiring than they should be," said John Radsan, a counsel with Afridi, Angell & Pelletreau and Associates with the Eurasia Group.

ILSA, however, has failed to promote the "supposedly politically secure," yet costly, Baku-Ceyhan pipeline from the Caspian Sea. "The problem with the American-supported Baku-Ceyhan line is that it needs to be a big, one-time project," Frazier said. "In the meantime, a number of smaller projects have succeeded in carving away at the profitability of the Baku-Ceyhan line."

In turn, operating companies are questioning the practicality of becoming involved, as there probably will not be enough near-term crude throughput to achieve a reasonable rate of return.

Last December, Deputy Oil Minister Hosseim Hazempour Ardebili announced that Iran will reduce its charge for exporting oil for Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. As a result, the Iran oil swap line will become more competitive with Russian routes and will introduce a higher cost of entry for the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline. For Turkmenistan oil, the fee will fall to $16/tonne from $21/tonne. For Kazakhstan, the price will drop to as low as $13/tonne.

US oil returns

Yet even if ILSA expires, US companies will still be barred from conducting, or even discussing business deals in Iran. "If someone could point to particular progress in arms of mass destruction and terrorism, a case could then be made on Capitol Hill to relinquish US sanctions," Radsan said.

What US oil companies hope for is the removal of Executive Order 12957 (effective Mar. 16, 1995), which strictly prohibits US involvement in petroleum development (see related article, p. 00). "This can go away with the signing of a pen," he added.

Yet as bilateral relations improve, many analysts believe that US sanctions will be lifted eventually and US companies will be allowed to return. This optimism, however, may easily be short-circuited if there is further evidence of Tehran's efforts in support of terrorism, building arms of mass destruction, or unraveling the Arab-Israeli peace process.

Working in the favor of the US companies is Iran's decision to reevaluate terms for the buy-back contracts. "Everything is going to be delayed, which is good for the American companies, as it will give them some time," said Hossein Ebneyousef, president of International Enterprises at a Eurasia Caspian Sea forum. "This subject is being revisited, as the Iranian government feels the rate of return and length of contract may be too high."

According to the Iranian constitution, foreign companies are prohibited from obtaining petroleum rights on a concessionary basis. To bypass this law and promote foreign investment, the 1987 Petroleum Law permits the establishment of contracts between the Ministry of Petroleum, state companies, and local and foreign natural persons and legal entities.2

"Buy-back contracts are just service contracts where the oil companies act like service companies," Ebneyousef said. Thus, these contracts are set up so that the contractor funds all investments. In return, the contractor recovers its investment from a commercial field and receives remuneration from NIOC based upon a predetermined rate of return (currently 15-17%). "When NIOC did the original contracts (with Shell and Total), oil was cheap, and Iran accepted the price risk." Thus, as prices drop, NIOC has to sell more oil to comply with the compensation terms. On the other hand, foreign companies have no guarantee that they will be permitted to develop their discoveries.

US law permits American companies to buy the bid packages but not to submit proposals. Yet "if the sanctions are lifted, there is a very good chance they will be involved in some of the larger plays," Ebneyousef said.

Either way, the recent past shows that Iran can and will forge its own path regardless of US policy.

References

- Ghorban, N., "Neka-Rey Pipeline: Boosting Economic Integration of Caspian States," Economic Magazine: Iran Today, May-June 1998.

- Alison, S., "Oil diplomacy brings Kazakhstan, Iran closer," Reuters English News Service, Feb. 6, 2001.

- Energy Information Administration, www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/iran.html.

US sanctions on Iran: a primer for US companies

The following is a primer on rules and laws affecting the scope of US companies' involvement in any business dealings with Iran, which is restricted by US government sanctions and other considerations.

This material was adapted from a presentation by Afridi, Angell & Pelletreau LLP to the Eurasia Groups Caspian Basin Forum-Economic & Political Developments in Iran, Nov. 28, 2000.

Rules and exceptions

"United States persons" are generally prohibited from exporting goods or services to Iran and from investing in Iran. "United States person" is broadly defined to include US citizens, US permanent resident aliens, entities organized under US law, or any person located in the US There are narrow exceptions to this export ban. In July 1999, new regulations were issued to allow some exports of food, medicines, and medical equipment to Iran under specific conditions. However, export guarantees and trade financing are still not permitted.

Transactions related to Iranian-origin goods or services are also generally prohibited. There are narrow exceptions to this import ban. In April 2000, new regulations were issued to allow some imports of' Iranian-origin carpets, caviar, and nuts. The sanctions are complicated enough that, whether a US exporter or a US importer, one should consult with legal counsel before trying to take advantage of any of these exceptions.

Travel by US persons to Iran is not banned. Accordingly, US business representatives have been traveling to Iran to attend conferences and to assess the business climate. Because US law prohibits financial transactions that involve Iran, however, it is not permissible to use credit cards to pay for expenses in Iran.

Gray areas

The exchange of "informational materials" is an exempt transaction under the sanctions, while the conducting of technical or feasibility studies for Iranians or the government of Iran is probably not exempt even in cases where no payment is received.

A fine line therefore exists between providing public information (permissible) and providing value-added analysis (impermissible). Similarly, a fine line exists between meeting with Iranian officials and businessmen (permissible) and negotiating with them (impermissible). Negotiating deals or making executory agreements, that is, agreements that would only take effect when sanctions were removed, runs afoul of the sanctions. In short, when talking and exchanging of information drifts over into "dealing" or "transacting business," that discussion has gone too far.

US corporations may participate in conferences in Iran but may not cosponsor conferences with Iranian entities whether held in Iran or elsewhere. US business representatives giving presentations at such conferences should take care to limit the content of their presentations to publicly available information.

Sources of law

For US companies, the White House's executive orders and the Department of the Treasury's Iranian Transactions Regulations are more restrictive than Congress's Iran-Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA).

ILSA is thus most relevant to non-US companies, prohibiting investments of more than $20 million/year in Iran's petroleum resources. The US president may issue "national interest" waivers to ILSA, as was done in May 1998 with respect to the TotalFinaElf/OAO Gazprom/Petronas investment in South Pars field. Before its departure, the Clinton administration was still "studying" the effects of other investments in Iran, such as those proposed by TotalFinaElf predecessor Elf Aquitaine SA, Bow Valley Ltd., and Royal Dutch/Shell. Unless renewed, ILSA expires on Aug. 5, 2001.

Enforcement and licenses

The treasury department's Office of' Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is the lead agency in enforcing the sanctions.

OFAC has the authority, in response to written applications and after an interagency review, to issue "licenses" for specific exceptions to the sanctions.

For example, in December 1999, a license was issued to allow seven Iran Air 747 airliners to have their wings refitted for safety. OFAC will also issue advisory opinions.