Remote-controlled operations to benefit drilling industry

Drilling contractors expect to drastically reduce cycle times as operators gain experience handling the automated drilling equipment installed during the current deepwater construction cycle.

By yearend 2001, 29 new or refurbished semisubmersibles and 16 drillships will have been added to the deepwater fleet, many of which have advanced pipehandling systems, automated fingerboards, top drives, multiplexed blowout preventers, and integrated drill floors.

Yet industry leaders feel innovation will continue forward as telecommunications and internet technologies provide enhanced means to monitor, maintain, and even operate drilling equipment from remote locations.

Evolution

Past trends in modern technology development provide insights as to where the industry is headed. According to Phil Vollands, product manager of pipehandling for Varco International Inc., the drilling sector has undergone three eras of technology evolution: mechanization, semiautomation, and local automation.

The first era, which began in the 1970s, can be portrayed through components used to reduce physical labor on the rig floor. Much of this equipment, which is located near the rotary table, included power slips, iron roughnecks, and top drives.

The era of semiautomation, which began in the mid-1980s, then expanded to include components used away from the rotary table. This equipment included piperacking and pipehandling systems that assemble single drill pipe joints from a horizontal position then rack them back in the derrick as doubles and triples.

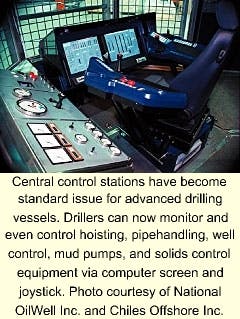

By the end of the 1990s, with the delivery of the new deepwater drilling vessels, technologies from both eras finally came together as manufacturers used programmable logic circuits (PLC) as a point of integration for all drilling components. With this technology, personnel could handle drillstrings, bottomhole assemblies, and casing without interrupting the drilling process while operating mud pumps and solids control equipment through central control systems.

As this has occurred, work roles have changed as drilling and technical personnel learned to operate, maintain, and repair the advanced hydraulic and electronic components.

On the more advanced vessels, for example, drillers handle the drillstring from an computerized cabin from which they can communicate instructions to the hoisting system and iron roughneck via joystick. Simultaneously, assistant drillers perform stand-building operation in preparation for the next connection or trip without shutting down the drilling process.

In exploration scenarios, drilling contractors are already enjoying cycle time improvements by as much as 15% with these new systems, with further efficiencies expected as time goes on (OGJ, Dec. 18, 2000, p. 32).

A problem of people

Yet personnel shortages expected in the near future-a result of declining petroleum graduates, a "lost generation" of petroleum professionals, noncompetitive wages, and a surge of retirements-may force the industry to find new means to share human resources, reduce direct labor, and attract prospective employees.

"We know we can retain and hire better-trained people in the office than in the field because of the hard life style," said Varco CEO George Boyadjieff. "Because of this, we want to see if we can operate the equipment remotely."

Steps are already being taken so that technicians can manipulate machine settings and analyze equipment performance from the comfort of an office rather than the field. For example, PLC-enabled centrifuges used in solids control activities may soon be controlled from a distant location through the internet.

By making decisions based on rheological properties and formation type, conveyor differential and particle retention time will then be altered without human intervention on the rig. "This work does not require 24-hr/day supervision," Boyadjieff said, "but if we send a person to a rig, he becomes dedicated to that rig and will not be available for other work."

Furthermore, top drive, drawworks, and mud pump performance may be improved as remote monitoring allows technicians to track bearing wear, torque, input and output power, and oil temperature.

"Rigs are getting so sophisticated and large that the two or three maintenance personnel on the rig cannot do it all," said Mark Sorensen, vice-president of National OilWell. "They are too busy just checking out systems."

Remote control

Boyadjieff says that four areas of activity can be conducted through remote technologies:

- Remote operators will be able to monitor activities in real time. With this data, it will be possible to analyze performance from an historical perspective and use this information to detect problems and enhance operating efficiencies.

For example, it will be possible to monitor how long it takes to pull a stand, so this information can be compared with similar units on other rigs. By looking at the workflow procedures from unit to unit, it will then be possible to make recommendations as how to best use the equipment. - Second, maintenance personnel will be able to detect problems that affect "the health of the system." In this way, diagnostic and predictive measures can be performed and provided to field personnel so that they can concentrate on the drilling operation instead of maintenance activities.

- Third, remote operators will be able to change system parameters through the internet or other telecommunications technologies, i.e., satellite.

- Finally, programming engineers will be able to remotely update systems with new versions of software that provide new or enhanced functional capabilities. Obvious analogies include virus and application updates that can be downloaded online.

A new era

All of the technologies detailed here can be built today. For example, Caterpillar Inc. utilizes smart chips in its engines to monitor wear and tear. And several office-based operators are already plumbed into the rig through National OilWell's web-enabled system in order to monitor and analyze drilling parameters in real time.

Finally, integrated PLC systems have proven to be viable tools for direct machine control over hoisting, pipehandling, and well-control activities. Thus, it becomes a matter of linking all these technologies together.

Unfortunately, many barriers exist that can prevent the introduction of remote-controlled machine operation. For example, how will a service company ensure the information remains classified? And what kind of redundant telecommunications technologies need be installed to ensure 100% connectivity between the control center and rig?

Yet in the end, the ultimate question will focus on whether these technologies will trickle down to the shallow-water and onshore markets so that the industry as a whole will benefit.