Fresh opportunities arise in Russia as country's oil majors respond to lessons learned from the 1990s

A radical restructuring of Russian oil company assets, the continued movement towards competitive petroleum markets, and reduced risk through updated production-sharing agreements (PSAs) may at last provide Western operators with a successful means to invest in Russia.

Unfortunately, Western investors, at one time optimistic about the prospects of Russian investment, have become disenchanted with one of the largest remaining underexplored petroleum provinces in the world. As a result, some Russian oil companies have seriously evaluated the lessons learned throughout the 1990s, establishing new business models and making tough decisions with regard to organizational structure, asset development, social-industrial ties, deployment of human resources, and market strategies.

What follows is a case study of one Russian oil major, Yukos, that illustrates how such lessons were learned and how its business strategies were developed in response to that educational process. The second part of this series, scheduled for next week's issue, will focus on how joint-venture and other opportunities for investment in Russia are opening up for foreign oil companies.

A Russian company

Yukos provides a unique insight into the evolution of a Russian oil company, as it has dealt with problems related to organizational development, mergers, Western alliances, and social-industrial symbiosis.

This company, which now ranks among Russia's largest oil firms as No. 1 in terms of oil reserves (17.25 billion bbl comprising Russian reserves categories A + B + C1)1, No. 2 in terms of oil production (327 million bbl/year), and No. 1 in terms of refining (167.44 million bbl/year), became the first integrated oil company in Russia in April 1993 (Decree No. 534).

In the early days of its existence, the then-state-owned company consisted of one production entity, Yuganskneftegas; three refineries-Kuibishev, Novokuibishev, and Syzran; and eight petroleum product suppliers in the Russian regions of Samara, Penza, Voronezh, Oryol, Bryansk, Tambov, Lipetsk, and Ulyanovsk (OGJ, June 14, 1999, p. 21).

In September 1995, the company grew again by adding Samaraneftegas along with a number of product marketing and research and development organizations. With these business units in place, Yukos held enough assets in central European Russia to form a vertically integrated oil company.

Yet this initial transitional period created numerous challenges for Yukos and for all other state-owned companies struggling to adapt to a developing market economy. For example, although the company was new, it consisted of a number of older companies, each with its own management philosophy that often maintained Soviet-style strategies based on output quotas and barter economics rather than a focus on profitability.

Furthermore, Yukos's struggle to unite these disparate units into one company was complicated by an immature business model, mounting debts from its production enterprises, and the overall economic decline of the country.

Thus, by the end of 1995, the company underwent sharp declines in output, huge salary arrears, and the technical bankruptcy of its main production unit, Yuganskneftegas. At this time, its debt to the cash-strapped Russian treasury amounted to more than $3.5 billion.

It was under these circumstances that the government traded Yukos's state-owned shares to private investors-led by Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the Menatep bank-for hard currency, conducted through a series of tenders and auctions held in 1995-96. When the government was unable to repay the loans at the end of that period, Yukos subsequently became the first fully privatized Russian oil company.

As part of its purchase agreement, Yukos committed to a $350 million program that called for modernization of its oil refining capacity, investments in field development and remediation, and a comprehensive reconstruction of the existing oil sales network and tank farms.

In May 1996, Khodorkovsky replaced Sergey Muravlenko as CEO and proceeded to fully repay Yukos's debt to the federal and regional governments. In the first year following privatization, Yukos also received $1 billion in loans and investments, committing $900 million to drilling, capital construction, and field development to raise production capacity.

In December 1997, Yukos finally acquired a controlling stake in the Eastern Oil Co. (VNK), adding a third production entity (Tomskneft); the Achinsk refinery; the Tomsk, Novosibirsk, and Khakasia refined products supply companies; and several research, marketing, and transportation facilities.

Learning about mergers

Partly in response to the precipitous drop in world oil prices, Yukos next made an attempt to merge with Sibneft in January 1998, hoping this would cut costs and increase production rates in much the same way as the merger of Exxon Corp. and Mobil Corp. was intended.

In April 1998, however, the merger fell through as Sibneft's financial standing, as related to taxes and wage arrears, appeared to be worse than Yukos had expected (OGJ, June 1, 1998, Newsletter). Yukos also felt that future operations would be hampered by Sibneft's deteriorating relations with local authorities, further compounded by a power struggle with Sibneft shareholders who feared losing all control of the company.

Despite this setback, many Russian oil executives, including Khodorkov- sky, believe that the impulse to consolidate will continue, leaving four to six majors in place. Nontransparent asset valuations and cash flow problems among the more poorly run companies, however, may make further consolidation difficult.

On the other hand, friendly alliances, such as that between Orenburgneftegas and Yukos, where there is a long-standing work relationship and a good match along the supply chain, may lead to friendly mergers.

Unfortunately, from a macroeconomic perspective, further consolidation may actually hamper the industry's transition to a free market, as the process of demonopolization-with only 11 major Russian oil companies currently in business-seems to be reversing itself.

An early attempt

Yukos's first-hand experience with a major US oil company came early and evolved as an initial good working relationship that later turned sour.

Such stumbles were typical of initial relationships between Russian and Western oil firms during the 1990s, according to Thane Gustafson, research director for the Cambridge Energy Research Associates Eurasia team.

"We started out with two worlds of oil meeting one another," he said. "On one hand, you have Russia, which had been in isolation, while on the other hand, you have Western companies that had [developed a different set of technologies and procedures]. It's like two tribes that haven't met one another before."

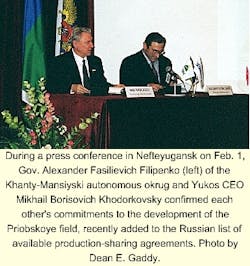

In September 1993, BP Amoco PLC forerunner Amoco Corp. was selected as winner of an international competitive bid round together with Yuganskneftegas to jointly develop the northern part of Priobskoye oil field in the Khanty-Mansiyski autono- mous okrug.

Since the bid award, these companies conducted a technical and feasibility study along with an extensive environmental assessment of the area, which was then submitted to the Priobskoye Bid Committee in June 1994.

With time, however, Amoco became disgruntled with the legislative obstacles imposed by the state Duma, while Khodorkovsky, who recently took over as Yukos CEO, sought to renegotiate more favorable terms. "We need an underlying legal framework to help protect our planned investment," said T. Don Stacy, then-chairman and president of Amoco Eurasia Petroleum Co., in an interview with the US-Russia Business Council.2

"For us to operate successfully in Russia, we must have stable, enforceable, long-term contracts that are beneficial to both parties." His prognosis foresaw the dissolution of the Yukos-Amoco Priobskoye alliance in March 1999.

At that time, Amoco said it had spent $140 million to explore and delineate the field, writing most of this off. Had the project continued, the company could have spent $8 billion to fully develop Priobskoye field, hoping to eventually produce 410,000 bo/d.

A new model

These events and the learning process that went along with them set the stage for major structural changes within Yukos in terms of technology management, corporate reorganization, and market focus.

In 1998, Yukos began to apply modern Western technologies by establishing a strategic alliance with Schlumberger, showing that Russian companies can successfully work with Western companies and that Western companies-albeit service-oriented-can make a profit in Russia.

Through this alliance, Yukos was able to outsource a significant part of its oil field operations in the Priraz- lomnoye field (OGJ, Feb. 7, 2000, p. 29). This helped Yukos to restructure and shed many of its own service enterprises, decreasing the cost of well servicing by 22%. Subsequently, in 1999, the alliance upgraded 104 electric submersible pumps, applied a reservoir waterflood program, and frac-treated numerous wells that added an additional 50,000 bo/d to field production.

Schlumberger also recently applied a multistaged frac in Priobskoye field, the first of its kind in Western Siberia, and has utilized advanced procedures to pump fluids downhole at different stages in order to identify frac-fluid behavior. For the past 3 years, Yukos has spent $1 billion/year on its oil field services.

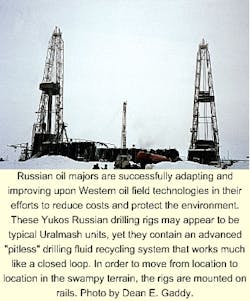

To protect the environmentally sensitive Ob River, Yukos engineers also designed an innovative "pitless" dril-ling-fluid recycling system integrating a combination of Western and Russian technologies including centrifuges and flocculators. This technology, typically found only offshore, has set a new world standard for onshore drilling operations.

A major restructuring

In late 1999, Yukos completed Phase II of its restructuring program (OGJ, June 14, 1999, p. 21).

Acting on what it learned from Amoco and the advice of Arthur D. Little and McKinsey & Co., Yukos realigned its upstream and downstream operations into two entities: Yukos Exploration & Production and Yukos Refining & Marketing. A third management entity, Yukos-Moscow, became responsible for strategic planning and management.

Seeking to absorb new thoughts and ideas into the company's business culture, Khodorkovsky also hired more than 20 middle and upper-level managers from a variety of companies, such as BP Amoco, Elf Aquitaine SA, and Kvaerner AS, an increasingly common practice among Russian majors (see related story, p. 28).

"There is a French chief financial officer, an American production manager, a Canadian service manager, a British training manager...," said Hubert Thouvenot, senior vice-president of Yukos Exploration & Production and former Schlumberger vice-president.

In general, Khodorkovsky has strategically placed key Western personnel in the functions related to reservoir-production management, finance, personnel, well-construction services, communications, business development, and exploration geology.

With regard to training, Yukos also breaks tradition by rotating personnel from business unit to business unit and from the field to the office.

Learning from the past

Khodorkovksy, who has placed a lot of thought on how to work with Western firms in the future, feels US and European companies must also reevaluate prior mistakes.

"If we analyze the reasons why Western oil companies have failed in Russia," he told OGJ, "we can arrive at one very simple answer. If you work in Russia, you must send in your top people-or don't come in at all." Khodorkovsky feels that the best Western specialists were instead sent to South America, the North Sea, and Middle East instead of West Siberia.

"Our industry is quite mature, and the people who work in it are quite good. Thus, Western graduates have nothing to teach us," he said. Although he acknowledges modern management practices are superior, he feels Western companies did not correctly apply them in Russia.

"The surprise that some of the Western companies felt when they had done everything according to American standards and rules-and failed-should not have [caught them off guard]," he said. "Russia is not ready to trade in its national language for investment, nor will it convert to Anglo-Saxon law, any more than America would [undertake the reverse]."

Instead, "They should have said, 'We are going to study Russian law and bring in people who can work within the framework of Russian law in compliance with Russian traditions and culture.'"

References

- For a description of updated Russian reserves definitions, see Eastern Bloc Energy, June 1998, p. 22.

- Russia Business Watch, Winter 1996.