Investment Opportunities Starting To Open Up In Iran's Petroleum Sector

Despite a major opening in the Iranian oil industry in the past few years, Iran still is a mystery to the international investor.

Years of isolation, bad press, and TV images of the hostage situation continue to loom in the minds of many investors. Iran is still seen by many as anti-Western (particularly, anti-American), run by religious mobs, and even unsafe for outside visitors. For us as expatriate Iranians living in the US and the UK, such superficial views have little validity. While we both feel that Iran has much to do to improve the environment for private investment, we believe there is a genuine desire to open up the economy in general and the oil industry in particular to the outside world.

While the rhetoric may sound harsh, the reality is that there are no real anti-Western or anti-American sentiments. Indeed, the Westerners who have visited Iran are often shocked by the warmth and welcome of the ordinary people. Everyone in Iran from almost every political persuasion knows the path to the future is through opening up the economy and reaching out to the world. Nowhere is this conviction stronger than it is in the Petroleum Ministry and affiliated companies National Iranian Oil Co., National Iranian Gas Co., and National Petrochemical Co.

Translating the convictions to realization of practical objectives has not been easy, due both to the volatile internal politics and to the lack of experience. Mistakes have been made, and there is room for a great deal of improvement. But the intention to reach out is there. With the intention will come practical measures to correct past errors and to improve contracts and procedures. We remain optimistic that the future will be positive, but there are no quick fixes. Patience is of the essence.

What are the opportunities in the oil and gas sectors in Iran? What kind of vision is needed to get there? We would like to focus on several key issues that are by no means exhaustive, but may provide a snapshot of the potential that may lay ahead. These issues center on key upstream issues that are of the highest priority but also include other issues that are much less talked about. Because of a lack of space, we will discuss the upstream issues in more detail and will briefly touch on the other subjects.

- Buy-back contracts vs. product-sharing contracts (PSCs).

- Central Asian swaps.

- Natural gas export issues: long vs. short pipelines vs LNG.

- Condensate splitting and private refining.

- Bunkering outlook.

Investment environment

First, a comment is warranted on Iran's general investment environment.

In Iran, the role of the government in the oil industry has been paramount-even before the revolution. The government has controlled all aspects of the oil industry, from the large upstream projects to service stations and even to lube oil sales. There has been no history of private sector involvement in the oil industry.

Although things are changing slowly, the need to get the private sector involved is urgent. First and foremost, there is a need for domestic private sector involvement, to be followed by alliances, partnerships, and direct investments by foreign companies. The oil industry is starved of investments because of the massive competition for access to oil revenues that account for about 90% of foreign exchange income in Iran. Much of the oil revenues continue to be directed toward subsidies in the food and agriculture sector, followed by the industrial sector and defense. The oil industry, the lifeblood of the economy, has to struggle to gain access to funds. Iran's legislation gives NIOC and other affiliates very little flexibility compared with national oil companies in the other Persian Gulf countries. Lack of funds, bureaucratic obstacles, and lack of an enterprise culture within the government is a fundamental problem that can be resolved only by passing on some of the responsibilities to the private sector.

However, in order to attract greater foreign investment, there is a need for much clearer and decisive domestic legislation in favor of the private sector. (The big problem in Iran is the domestic jockeying for position among different factions. This sends a very mixed message to the outside world and is negative for potential investors.) Above all, there must be a clear, long-term program for encouraging private individuals and institutions to buy bonds or shares in all major sectors of oil and gas activity. The idea that oil and gas activities should be kept essentially as a state monopoly should be questioned, given the many benefits that have been gained in other countries where such private sector activity has been encouraged.

In encouraging private sector investment in the oil and gas sector, emphasis must first be placed on encouraging the domestic private sector. Foreign private investment can never take the place of domestic private investment. It must be seen as complementary to and not a substitute for the domestic sector.

New opportunities

Iran's upstream sector is the most important producer of foreign exchange for the Iranian economy and thus represents the best opportunity for investment.

Its production capacity has declined from a peak of 6.7 million b/d in 1978 to about 3.5-3.7 million b/d today, with peaks of around 4 million b/d possible. The natural decline has set in at many fields, and production declines are inevitable on a large scale without secondary recovery and additional drilling.

Offshore production has declined both due to the lack of investment as well as due to the war with Iraq, as compared with the pre-revolutionary volumes. Since 1992, offshore production has been rising slowly but is well below the targeted 1 million b/d set by the government in the early 1990s. Iran is offering both offshore and onshore buy-back contracts, hoping to be able to reverse the declining trend. If all goes according to the government's plans and expectations, production capacity may rise by about 2 million b/d by 2005-06, but capacity declines in the older fields of 0.5-1 million b/d may well offset some of the gains.

Given the critical importance of higher production to the future of Iran's economy, it is natural that much of the focus of the Ministry of Petroleum and NIOC has moved toward buy-back contracts.

It may be recalled that Iran offered about 43 onshore and offshore fields under the buy-back formula to foreign oil and gas companies at a conference in London in July 1998. Prior to that date, Iran had already concluded its first ever buy-back deal with TotalFina SA and Petronas covering the Sirri A and E structures in the Persian Gulf.

Table 1 shows the status of the existing buy-back contracts, the list of potential new contracts, and the potential impact on Iran's production capacity up to 2005. In most cases, the potential capacity of the fields in question is far higher than original NIOC estimates and is based on reported submissions by companies interested in signing buy-back deals as well as certain other industry sources. Total additional capacity by 2005 from these fields is expected to be about 1.8-1.9 million b/d.

In addition, recent additional discoveries have been made by NIOC. These cover two onshore oil fields near Ganaveh with combined reserves of over 100 million bbl, as well as other new reservoirs in existing fields-such as Bibi Hakimeh, which is currently producing 140,000 b/d, and Gachsaran, producing 500,000 b/d.

Iran has also reported a huge new discovery near the Iraqi border. The "Azadegan" field was announced by the Ministry of Petroleum to have a production potential of 400,000 b/d by 2003. Because the "Azadegan" discovery is based on a single well, "Nir Kabir," it may be premature to assess such a large production capacity to it at this moment.

NIOC is also keen to sign buy-back deals for new exploration areas. Some initial steps have been taken with regard to Caspian exploration, representing the first foreign involvement in Iran's Caspian waters and Royal Dutch/Shell's first oil contract in Iran since the overthrow of the Shah in 1979. Shell and Lasmo PLC announced that they had chosen the blocks they hope to develop with Iran as part of an exploration study. Under the accord with NIOC, the two companies now have to reduce the choice to two areas and have to negotiate buy-back agreements within a 12-month period. The accord also grants them preferential rights for up to two more blocks where seismic work had not previously been carried out.

According to recent reports, NIOC is also preparing to launch two new Caspian exploration tenders aimed at foreign oil companies over a 1,000 sq km area close to the Iran-Azerbaijan maritime border.

Iran is also expected to seek exploration contracts for at least some of the new acreage available in the Persian Gulf area and possibly new areas onshore as well.

Obviously, any new finds would add to the estimated 1.8-1.9 million b/d of additional capacity expected by around 2006. Foreign private activity in Iran's upstream would be boosted further if the country were to offer more flexibility in the buy-back concept and, even better, move towards PSCs that are inherently much more flexible than buy backs.

Since reopening to the outside world, Iran has employed the buy-back framework for upstream contracts. The first such contract was signed in 1995 in relation to the Sirri offshore oil field. The essential meaning of the word buy-back is a service contract in which one or more parties are contracted by the Ministry of Petroleum (NIOC, NIGC) to carry out necessary exploration and development work on a field, which once completed, reverts back wholly to the ministry. Buy-back contracts are generally designed by the Iranian side to last 5-7 years and are thus fairly short-term in the context of the traditional upstream contract. In return for its services, the contracting party or group is paid a guaranteed net rate of return that has so far tended to be about 15-18%.

We believe that the buy-back principle contains certain shortcomings that need to be addressed sooner rather than later. However, we would disagree with those who view the original adoption of the buy-back formula as a mistake. One needs to see its adoption in the Iranian political context-that is, in the context of repeated statements by senior Iranian leaders up to the early 1990s that foreigners must never be permitted to engage in oil and gas activities in Iran. Thus, we believe that the adoption of the principle represents a radical break with the past and was a courageous move that carried huge political risks for those who espoused it originally in Iran. However, it is now time for the Iranian authorities to move on. Otherwise, Iran could, over time, fall short of its expectations in terms of attracting sufficient foreign and domestic private capital to the sector.

Buy-back shortcomings

The key shortcomings of Iran's buy-back contracts are as follows:

- There is a fixed rate of return. This may be of advantage to the foreign party, especially at times of low oil prices. However, in general, it provides no incentive for the foreign party to improve total returns from a project. We are using this expression in a general sense to include discovering additional reserves, employing techniques to increase the recovery ratio, introducing cost-saving measures, and optimizing production targets.

- The life of the contract is too short. This is particularly true in the case of natural gas, which is far less developed in terms of an industry in this region of the world than oil. In addition to the factors mentioned above, the short duration of the contract provides little incentive for the foreign party to introduce measures to maximize the life of the field in question over, say, a 20-year period.

- The terms are inflexible and generally not subject to renegotiation. There is no room for adjusting the terms, for example, in the face of unforeseen developments. There is thus no sense of partnership. The foreign party is there to do its job over a short period of time and then is told to pack up its bags and go. Such a situation hardly creates mutual trust between the two sides. Once again, it needs to be stressed that gas is a long-term business that is not suited to short-term contracts.

- Transfer of capital and technology. The brief duration of buy-back contracts limits the extent to which foreign capital can be employed over time. It also acts as a disincentive for the transfer of technology on an ongoing basis. Why should the foreign party employ its latest state-of-the-art technology in a buy-back deal only to see it being taken over totally by the Iranian side once the development phase ends? Iran has a lot to learn in terms of the technology of gas, especially if it wants to get into the LNG export market.

- Transfer of management skills. This is where, we believe, the buy-back concept suffers from its greatest single shortcoming. We do not doubt the immense expertise existing within the Iranian oil and gas sector. However, that sector has been isolated from the tremendous changes in the international oil industry for the past 20 years and needs to get up to speed as soon as possible. Today, the key to optimal development of projects is the harnessing of human resources and skills. Transferring technology is one thing; utilizing it in an optimal manner is another. The transfer of such skills takes years and would be more likely if upstream contracts were signed for a longer period of time, thereby giving the foreign party an added incentive in agreeing to such a transfer of management skills and expertise.

Moving to PSCs

In recent months, some influential voices in Iran have been advocating the signing of PSCs for upstream schemes.

This is something that we have been advocating for some time. In our view, it would, over time, provide a significant boost to private sector activity in the Iranian oil and gas sector. The problem is that, up to now, there has been confusion among some senior Iranian officials about what production-sharing actually means. Some political circles in Iran have tended to confuse it with direct ownership of reserves. The latter is not an absolute necessity or condition for PCSs. The Islamic constitution bans direct ownership of the country's mineral wealth. However, Iran has no constitutional ban on PCSs that do not include entitlement to reserves in the ground. Besides, although in an ideal world, foreign oil companies would like to own reserves in the ground, this should not provide too much of a problem in Iran. The country's huge oil and gas reserve base is sufficient in itself to attract many potential foreign partners.

It sometimes comes as a bit of a surprise or disappointment to Iranian negotiators that foreign companies generally insist on a high rate of return from potential projects in Iran, partly to offset what they see as relatively high political risk. Such an assessment of Iran is not altogether unfair, given that the country has nationalized assets in the past, is a member of OPEC, generally prefers commercial disputes to be considered by Iranian courts rather than via international arbitration, and is located in an area that has seen repeated conflicts and instability in the past.

However, there are many things that Iran can do to allay concerns about political risk. Fear of political risk on Iranian projects can be increasingly offset by Iran over time by the establishment of a sound track record on future upstream deals. A policy of accessing international capital markets, involving roadshows in which senior Iranian oil and gas officials and executives come face to face with leading international and regional financial institutions, will also prove of tremendous benefit to Iran. The outside world will become increasingly familiar with the Iranian oil and gas industry, and Iranian executives will in turn become more familiar with the hopes and fears of foreign investors. We are certain that in the end, as the saying goes, familiarity will breed success.

Greater familiarity between Iranian officials and potential investors should, it is hoped, pave the way for greater flexibility in upstream agreements. If there is one fundamental criticism of the buy-back concept, it is that it is totally inflexible. It locks both parties into a framework that is so rigid that there is no room for modification of the contract in the event of changing circumstances. On the negative side, unforeseen costs, reservoir performance, regional events, sudden changes in capital markets, etc., could place the foreign party under huge financial pressures, which might threaten the very deal in question. At the same time, the foreign party has no incentive to improve reservoir performance following signature of the deal and cannot seek better financial terms in line with packages that may become available elsewhere in the region and beyond.

We are not suggesting constant renegotiation but rather a flexible approach by both parties which, over time, will create greater confidence and promote a better climate for investment in Iran. Governments that take such issues into consideration during their negotiations with foreign companies can significantly reduce the possibility of future conflicts. Of course, no contract is perfect. Governments and oil and gas companies should view contracts as heralding the beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship between the parties. Such contracts could be subject to changing conditions that might at times require some alterations to the original agreement.

Our confidence that Iran's upstream reforms will deepen over time is underscored by the very nature of Iranian politics and religion. In Iran, there is an important principle called "Maslehat." The nearest English translation is "expediency," or perhaps in this case, "national interest." In other words, certain actions are permitted, even if they may seem to run counter to the Islamic constitution, provided they serve the greater national interest and well-being. Today, one of the highest wielders and arbiters of power and authority in Iran is suitably called the Council of Expediency. This council can intervene in the political process to prevent deadlock on key policy issues.

Certainly, as far as we know, the Islamic constitution does not prohibit equity ownership in oil and gas. What it prohibits is "emtiaz" or concessions. These were the types of agreements that were common in Iran before the Islamic revolution. Foreign companies were allowed unilaterally to explore for, develop, and produce oil in vast areas of Iran over a period of 2-3 decades and retain ownership of the oil and gas in the concession area. The world has moved on a long way since then. The operating word in the world of oil today is not concession, but partnership, or "mosharekat." In other words, it is based upon the principle of equity-an agreement among equals. This means equal rights but also equal responsibilities. Today, fewer and fewer countries continue to prohibit equity partnerships in the oil and gas sector.

Central Asia swaps

The issue of export pipelines from Central Asia and the opposition of the US government to any exports via Iran is well known and documented. We believe that the US government's policies so heavily focused on stopping swaps with Iran will go down in history as one of the biggest energy policy-foreign policy blunders of the Clinton administration. To try to oppose natural forces of economics and geography for dubious and unclear strategic goals is harmful to the US national interest and to the interest of Central Asian countries. The only winner from this blunder will be Russia.

The swap issue of great importance is the Neka pipeline connecting Iran's Caspian port of Neka to a pipeline grid taking Central Asian oil to the Tehran and Tabriz refineries. The pipeline will carry about 300,000 b/d of oil transported by tankers across the Caspian Sea to Neka. Currently, about 20,000-30,000 b/d is transported via older, smaller pipelines. Iran had intended to tender and award a construction contract for the pipelines to foreign companies. Due to a series of miscalculations, foreign contractors did not participate. The government brought in a local Iranian construction company that was later deemed to be unsuitable. The final stage of negotiations with Chinese state firms China Petroleum Corp. and China National Petrochemical Corp. did not end up in a firm contract. Iran's efforts to secure the lowest cost and squeeze the foreign operators prevented this, although negotiations were reported to have resumed in January (OGJ, Feb. 7, 2000, p. 42).

Now, it seems that the government has adopted a more positive and constructive attitude. We believe there is now a reasonable opportunity in constructing this pipeline in a consortium involving some key Iranian companies as well as owners of oil in Central Asia. Iran's NICO (Naft Iran Co. and Dubai's Emirates National Oil Co. (owner of Dragon Oil in Turkmenistan) are potential joint-venture candidates for an international company to build the line. Other foreign companies may also be interested in participating in such a consortium. The logic of the line supersedes the short-term political difficulties.

Natural gas pipelines

Almost every discussion of natural gas exports in Iran is focused on long-term gas exports to Turkey and India and gas imports from Turkmenistan.

While Iran's exports to Turkey may shortly begin on the strength of imports from Turkmenistan, the fact remains that long-distance export to India may come at a very distant future, if ever. There is genuine intention both on the part of Iran and India to build such a pipeline, and there are high-level discussions under way between the two governments. However, the thorny problem of exports via Pakistan and the concerns of India on reliance of such a route is likely to delay such a project for sometime. Likewise, despite a genuine desire by Iran to export LNG, the realities of the oversupplied LNG market in Asia means that exports from Iran are 1 and possibly 2 decades away from reality, if ever.

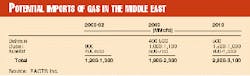

There are, however, closer markets that can buy Iranian gas. These are Dubai, Kuwait, and Bahrain. Gas import requirements in Dubai are urgent and in Kuwait of some importance, and in Bahrain, the need will emerge in a few years. Table 2 shows import requirements of about 1.2-1.3 bcfd in the near future, rising to about 2 bcfd by 2005 and 3 bcfd by 2010. To this, one can also add potential import needs in Abu Dhabi and Oman, if new gas is not found. This is a huge market next door to Iran that can be tapped, for suitable economic terms and within a short frame of time. However, the competition is stiff, particularly from Qatar. If the Dolphin Project materializes, all these gaps can be quickly filled by Qatar. If Iran is to take advantage of such opportunity, the time to act is now. Iran is best-served to shift focus from long-distance exports to short-distance prospects in its own backyard.

Private refining, condensate splitting

There has been much talk about private refining in Iran. There has even been a proposal for a buy-back project in refining. There have been discussions of private refineries in the northern tip of Iran to be supplied by Central Asian crudes and the products to be sold in Iran in return for crude-product swaps in the Persian Gulf.

These are far-fetched proposals with little realistic prospects. Not only are the domestic prices in Iran the lowest in the world-not conducive to private investments-but also refining as a whole is likely to remain oversupplied and depressed in the East of Suez markets for some time to come.

In contrast, condensate splitting may have some prospects. Iran's South Pars gas is very wet. Each 1 bcfd of gas is likely to also yield 35,000-40,000 b/d of condensate. With the eight phases planned for South Pars, Iran could be looking at 250,0000-300,000 b/d of condensate within a decade. Iran had envisaged a 70,000 b/d splitter at Bandar Asaluyeh, but it seems that the proposal did not make it to the third 5-year development plan.

By 2001-02, Iran will begin to have a bigger condensate surplus, and splitting projects based on the new output are likely to materialize. It is possible that foreign companies producing the gas might themselves wish to build the splitters. One way or the other, splitter projects in Iran will become inevitable.

Bunkering projects

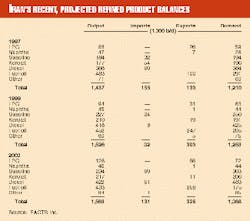

Iran's product balances have shifted significantly in the past few years (Table 3).

In 1997, Iran was a major importer, of about 155,000 b/d of products, and it exported about 100,000 b/d of fuel oil from Abadan.

The commissioning of the Bandar Abbas refinery has changed the picture dramatically. By 1999, Iran's imports had shrunk to only 32,000 b/d, and exports had escalated to over 300,000 b/d. By 2002, Iran's import requirements of diesel and gasoline will begin to increase again without additional refinery construction, but fuel oil exports will continue at a very high pace.

Iran is a major fuel oil exporter. Indeed, Iran's fuel oil exports have reached about 250,000 b/d in 1999 and are likely to stay at that level for the medium term. Had it not been for the strong fuel oil import requirements from Asia, the Iranian fuel oil exports could have single-handedly depressed fuel oil prices east of Suez.

Next to Iran is the UAE sheikdom of Fujairah, which has a world-scale bunkering operation in full swing. Fujairah is bunkering about 200,000 b/d of fuel oil and has emerged as the second largest bunkering operation after Singapore in the East of Suez market. Ironically, UAE is a minor exporter of fuel oil. Most of Fujairah's bunkering supplies comes from Iran and is supplemented by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

Some have begun to ask the question, why should Iran not be able to build a major bunkering operation itself-given that most bunkering supplies originate from Iran. There is clearly room for a major bunkering operation in Iran, and there are several proposals under discussion. Whether the government can attract strong enough interest from the investors and provide the right economic environment for such a free trade zone remains to be seen, despite the obvious potential for such a facility. There is however, a clear opportunity in this area.

Conclusion

Iran is one of the few closed markets in the world. Iran has great upstream potential and a huge domestic market of over 60 million people.

The government intends to open the market, and the population intends to reach out to the globalized world, but there are structural and fundamental problems yet to be overcome. These problems range from political jockeying to the practical consequences of inexperience in a global market. Despite domestic political volatility and the US embargo, the walls that have separated Iran from the outside world will be crumbling over the next 2-3 years. We expect significant changes within Iran to speed up the openings in the oil industry. We also see the inevitable rise of the private sector in oil operations and the emergence of exciting opportunities for foreign companies in Iran.

The Authors

Fereidun Fesharaki is the president and founder of Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services (FACTS Inc.). Born in Iran, he received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran. He joined the East-West Center in 1979 and currently is a senior fellow and head of the Energy Project at the East-West Center. His area of specialization is oil and gas market analysis and the downstream petroleum sector, with special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region, Middle East, Latin America, and US. He is an advisor to numerous oil and gas and other energy companies, private and state-owned, and governments in the Middle East, Pacific basin, Latin America, as well as the US government. Fesharaki is the author of more than 70 papers, has authored or edited 23 books and monographs, and serves on the editorial board of a number of scholarly journals devoted to energy resources and economics. Fesharaki was the 1993 president of the International Association for Energy Economics. In 1989, he was elected a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Since 1991, he has been a member of the advisory board of Mitsubishi Oil Co. He is also an advisory board member of the Far East Oil Price Index, based in Singapore. Fesharaki is also a member of the Pacific Council on International Policy. In 1995, he was elected as a senior fellow of the US Association for Energy Economics for distinguished service in the field of energy economics. In 1998, Fesharaki joined the board of directors of the American-Iranian Council.

Born in Iran, Mehdi Varzi obtained a BSc in economics (special subject: international relations) from the London School of Economics and Political Science, London University. He obtained an MA in Area Studies (Politics and Economics of the Near and Middle East) from the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. Varzi was first employed as a senior analyst in the international affairs section of National Iranian Oil Co. during 1968-72. During 1972-81, he served as a diplomat in the Iranian Mnistry of Foreign Affairs. During this time, he was a personal assistant to the director general for economic affairs and a member of the secretariat of the minister for foreign affairs. Varzi was attached to the Iranian embassy in Ankara during 1977-81. During 1982-86, he worked as an oil consultant for stockbrokers Grieveson, Grant & Co., London, prior to their merger with Kleinwort Benson in 1986, when he was appointed assistant director (research) at Kleinwort Benson Securities. During 1987-95, Varzi served as director of Kleinwort Benson Securities' oil and gas research team, a title he has held since the firm's merger with the Dresdner Group in 1995. Since then, he has advised Dresdner Kleinwort Benson on potential opportunities in emerging markets and was instrumental in the firm's appointment as financial advisor to the National Petrochemical Co. of Iran-the first such appointment of a foreign bank in Iran since the 1979 Islamic revolution.