Integration seen as best business model for US refining-marketing

Adapted from a presentation at the Sept. 13, 1999, National Petrochemical & Refiners Association board of directors meeting.

The current state of the US refining industry is well-documented and widely acknowledged by those who participate in it and by the array of observers and analysts that follow it.

Thus it could go without saying that refining of crude oil and marketing of related products is part of a changing energy culture. Words such as consolidation, chaos, and turbulence have become part of the standard glossary for discussing a downstream segment marked by low margins, alliances, and mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

It is not possible to correctly predict the nature of the successful business models over the coming decade. But it is undeniable that for every company in the midst of today's reality in US refining and marketing, not adapting to ongoing change is not an option.

While the history of most industries has provided a useful road map for the future, virtually every leader in today's energy environment agrees that the past no longer reflects the shape or direction of the future. In fact, the lessons of the recent past echo one message: the future will belong to those who are constantly aware of the changing business landscape, and are willing to adapt and change to compete in the evolving new marketplace.

More than ever, customers will shape the industry at every level. In the past, drivers with strong brand loyalty may have wanted their favorite gasoline and oil. Today, consumers want gasoline-quick and cheap-regardless of brand. In addition, they may even want their soft drink, chips, and an assortment of convenient services. Consumer demands and new consumer profiles have created a kind of change that not only impacts the retailer but can have a dramatic impact throughout the hydrocarbon supply chain.

To be sure, the refining and marketing of crude oil will remain a part of the new energy industry big picture. The downstream segment faces an array of well-known challenges, and many new areas are being pursued by modern energy companies. For example, deregulation of utilities promises to open potential new markets for many industry players-including products and services historically unrelated to this industry. We even see many energy segment companies going to market with financial and risk-management offerings.

Recognition of this continuing and frequently dramatic changing of the industry structure, environment, and operating modes leads the search for definitions of new business models. Many observers agree there is a growing gap between the haves and have-nots, with many of the stronger companies able to continue to expand the breadth and depth of their assets and operations. The concentration of refining capacity in the US reflects the corporate consolidations in recent years. It is fairly easy to conjecture that M&A consolidations may vest the top 12 companies with 80% of US crude distillation capacity.

Just defining the right questions to address through strategy-development exercises is as challenging as the subsequent development of viable answers. It is fairly straightforward to ask the first question, Where are we today?, as a precedent to the overriding question, Where do we want to be tomorrow? The obvious and difficult challenge however, lies in determining the set of responses to: How do we make the transition? What will it take to compete tomorrow in a world of deregulation, e-commerce, and a global marketplace?

Where are we now?

A look at the capacity groupings shown in Table 1 reveals the ever-growing size and complexity of US plants and points out the vast differences that exist between the largest refineries and those of smaller scale.

When only refineries with processing capacity of 200,000 b/d or more are considered, we find that just 27 such plants represent about 46% of total US distillation capacity. These refineries have an average Nelson's Complexity Index of 12.0 and an average capacity of 275,000 b/d.

If the 61 plants with 100,000 b/d or more are grouped, they contain a little over three fourths of US capacity. Those plants in the 100,000-200,000 b/d category average 140,000 b/d, about half the average size of the top category. From this level, the drop to the smaller-size groups, which contain 100 plants, is dramatic.

The theme of the larger, more-integrated players distancing themselves from the rest of the pack can also be noted when the publicly available financial data are compared. Those data show the integrated businesses attain higher performance levels than do the more-focused refining-marketing companies.

Performance differences observed among the downstream companies-and the overall performance of many energy companies compared with other industry groups-lead to contrasting the strategy drivers of the past with those that are coming into prominence today. Companies in the past based their strategies on set plans driven by regional divisions and business segments. These strategies were principally asset-based, built around independent, stand-alone plans and actions. Today, strategic thinking is best characterized as an ongoing experiment responding to a rapidly changing marketplace-as opposed to a precise science derived from historical performance data. Financial cash generation is now the prime focus, and return expectations are key motivators, as opposed to the stand-alone strategies of the past, and joint ventures in many forms are now being given broad consideration.

While refinery operators can find it disconcerting to follow the talk of unique business models, new marketing paradigms, evolving strategic approaches, et al., the critical need for the downstream industry cannot be diminished. Firms that have crude oil to sell or markets to serve could not achieve their business goals if refineries and related downstream assets were not available. The downstream remains a vital and necessary segment to complete the hydrocarbon value chain. It is the undeniable need for refining that leads industry players to continue the search for the most robust and successful new downstream business models.

Global competition models

The once political catch-phrase "global village" helps communicate one of the essential marketing realities of the 21st century: The domestic enterprise is no longer completely unique or distinct from the global marketplace.

Any attempt to exist as an island may eventually become more devastating to an oil company in the coming decade than it was during the latter part of the 20th century. Even those companies doing business only in the domestic market are touched by the global industry, and, because of their impact domestically, they can have a measurable effect on the global market.

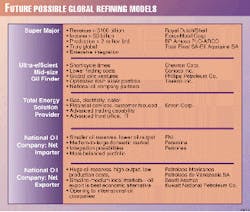

Five potential business models for global competitors are outlined in Fig. 1, along with examples of specific companies that may fit into each.

The ever-strengthening position of the Super Majors, each with annual revenues of more than $100 billion and oil production in excess of 2 million b/d, has been widely covered in the business press. These companies have achieved extensive integration and have largely become global "asset managers."

Smaller than the Super Majors, other substantial enterprises may find a new model we have styled as the Ultra-Efficient Mid-Size Oil Finder. Able to take advantage of short cycle times and lower finding costs, companies in this group may often find advantages through associating with national oil company partners. Their focus would be to maximize their flexibility and constantly optimize overall portfolios. The downstream sector of these companies would be a smaller portion of their overall enterprise and might frequently exist only to augment other segments such as production or chemicals.

The concept of becoming a Total Energy Solution Provider is perhaps the most unique of the prospective global models. Such companies would strive to offer a wide array of products and services from a single provider, effectively competing at the property line of their customers. Deregulated utilities and advanced technological capabilities are making real-time commodity management a present-day reality. The innovator Enron Corp. is widely considered as the initial architect and developer of this business model.

National Oil Companies account for the remaining two models defined in Fig. 1. We draw a distinction, however, between the traditional NOC that controls vast reserves and strives to maximize the financial benefits of production and exportation of oil and the NOC that operates in a country that has smaller reserves and often is an oil importer. While the exporting NOCs appear to be opening up for more international companies to enter, the importing NOCs may be prime candidates for further joint-venture activities with US or European companies.

US refining models

The results achieved by various US refining business models can be studied by dividing the operating companies into competitive groups. Table 2 suggests four categories for further consideration: Large Integrated Companies, Refiners with Production, Significant US Refiners, and Niche Players & Others.

For this discussion, we have chosen to compare the outcomes attained by each model-type through a historic tracking of the average firm value of the entities within each grouping. Firm value, the sum of equity market capitalization and long-term debt (less working capital), is an important factor in the analysis of most investment analysts, and it is an indicator of how companies are attaining their stated goals of value creation for their stakeholders.

Most striking, and in line with the previous discussion of the ever-growing influence of the large, fully integrated energy companies, is a comparison of the average firm values of each group. The chart provided in Fig. 2 makes the huge size discrepancy obvious. At nearly $130 billion, the average firm value from the group of Large Integrated Companies is an order of magnitude greater than that of the next highest group, the Refiners with Production. While the Significant US Refiners group has an average value that might be considered substantial at just under $3 billion, this is only a small fraction of the values for the top group. Refiners may have historically been able to think of their direct competition as the other plants in their vicinity or those with good logistical connections. The reality now is that the full scope of the Large Integrated Company is the true competitor. The colossal size of these businesses allows them the flexibility to experiment with any business strategies, any techniques of going to market, a wide array of product and service offerings, the latest technologies throughout their organization, and essentially any investment.

Firm-value trends since 1994 for the four groups are displayed in Fig. 3. While even the growth in value of the Large Integrated Companies has not kept pace with the climb of the Standard & Poor's 500 index, they have set the pace for the US refiner groups. During 1996-97, it appeared the Significant US Refiner group was achieving high stock market valuations; however, they were not able to sustain those levels in the face of the ongoing megamergers that have dominated the headlines. Those operations in the Niche Players & Others category offer mixed results depending on the characteristics of their business, and as a group, they began to show some encouraging improvement in the last two periods charted. Such operators always face concerns regarding the degree of protection their specific niche provides, their ability to make investments precipitated by regulatory compliance, and the possibility that others with an eye to increasing market share will eventually find ways to erode the features of the niche.

These value trends support integrated operations as a key for future business models. The Large Integrated Companies have E&P, refining, logistics, petrochemicals, and marketing and thus have a diverse risk profile as well as economies of scale and financial strength. The capital required to achieve this level of extended integration is huge and not available to every would-be player. Any consolidation must be carefully considered, with attention given to the specific goals and purposes of the companies involved. Just simply becoming a bigger company, with the same mix of assets, may not offer the desired level of improved appreciation from the investment community, and in fact may not lead to greater financial returns. Merger and acquisition opportunities certainly do not provide automatic answers. The search for the best business model will ultimately be fulfilled by those who are the most creative in their strategic approach. There is a growing, evident need for a willingness to experiment, test the market, and make real-time value decisions for strategic placement of products and services.

US downstream transactions

With the search for the best future business model for US refiners, the prospects of acquiring additional refining facilities will be frequently revisited.

The current conditions of the refining asset marketplace give mixed signals, as is shown by two quotes from a recent article printed in the Houston Chronicle:

"There are too many properties and not enough buyers," said the CFO of one Niche Refining company.

The chairman of a company in the Significant US Refiner group reported, "ellipseWe threw out what we thought was a good number, and we didn't even get in the data room."

The divergence of these observations is perhaps a reflection of the difference between the "good" refineries and the "less-desirable" ones-in a way, another take on the concept of the growing divergence of the "haves" and the "have-nots" within the industry itself. When 20 years of public data on refinery sales in the US are compiled and analyzed, we see that the average transaction has taken place at a value that is about 17% of the new replacement cost of the subject refinery. This figure clearly indicates the huge risk associated with making new investments in a plant; however, it does show how a new owner can start off with a much lower asset base on which to calculate economic returns.

It is important to note that many of the transactions that took place in the last 2 decades did not involve the best and most productive refineries. The time of refinery shutdowns, bankruptcies, and rationalization that followed decontrol prompted many sellers to divest at virtually any price. In contrast, some of the refineries that are now becoming available as split-offs from the large mergers may hold more attractive value than those available in the past. But in light of continuing weak refining economics and the availability of some more attractive facilities, there may be a group of refineries for which buyers simply cannot be found.

Future business models

Any new US refining business models will develop with time and experience and will not be consistent through time. Thriving will require continuous responsiveness. The already discussed role of the large global players will not be settled anytime soon, and regulators continue to promulgate new restrictions on operations and products. Research into new and different processing options continues, and may some day give refiners an entirely different way to turn crude oil into salable products.

The old, asset-based models were easy to understand but are not likely to continue to yield satisfactory, let alone exciting, results in the future. The big mergers are about expanding scope and reducing costs. Companies not involved in those transactions must embark on their own programs to compete in the new low-cost environment.

Many current business initiatives are being pursued throughout all industries. Certainly these have direct application to the refining and marketing business in the US. Such things as supply-chain optimization, post-enterprise resource planning integration, and outsourcing of support functions can provide real and sustainable benefits. The emergence of e-commerce methods and systems can lead to lower costs but is only one of the recent popular initiatives that also offer prospects for market growth.

It is worthwhile to briefly review two business model concepts that have been considered, and, to various extents, are being implemented in the downstream. One is the notion of the virtual refining company, or the use of toll processing to supply refined-product market channels. This is a popular and effective approach to some consumer products, but it has not proven to be a good, sustainable fit for petroleum refining.

In refining, the products are nonproprietary, there are many by-product disposition problems, and multiple supply alternatives are always available. Large capital infusions are typically needed to maintain the plants and meet tightening regulations. If these characteristics were not enough to render the model unstable, we have the added problem of a manufacturing segment that works with very low margins and thus has little upside to offer in return for another party taking some of the downside risk. While toll-processing arrangements for entire refineries have been put in place in the past, they have not proven to be sustainable over the longer-term.

The concept of refining as an extension of crude production costs is more interesting, and we have many examples of this already in place. We all are familiar with the array of deals that companies such as the national oil companies of Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico have completed in the US. While these arrangements allow the crude oil producers to share in refining profits when they exist, that is probably not the primary benefit achieved. From public information regarding one of the more-recent transactions in this category, we can determine the more-important economic attraction. A field expected to produce 165,000 b/d of heavy oil over the next 20 years will supply a new conversion facility being built at a Texas coastal refinery. The producer that will supply the crude oil will make an investment of about $250 million and have a 50% interest in the asset. Think of this investment in terms of an element of the production cost of the field.

Allocating the US investment over the barrels of oil produced over the life of the field gives an effective increment to production cost of 21¢/bbl. This is a small addition to the cost of producing the oil, and it will secure the outlet for oil that might otherwise be difficult to place. This analysis suggests that some future business models may be derived from further transactions involving US downstream operations and producers of less-desirable grades of crude oil.

Developing a business model

A one-line strategy definition is a quick way to start the thinking process that we have found useful in assisting oil companies in the early stages of strategy reconsideration exercises.

It is a simple concept, intended to be a method of distilling a business focus to its essence. When key executives reach agreement on basic principles, that can become a springboard to help define the specific strategic model to be pursued. The recommended exercise is to develop one-line descriptions of both the present state of a company and the preferred future description.

The exercise is intended to develop a one-line statement that realistically describes where a company is in the marketplace and the destination or level it plans to achieve. The follow-up to this exercise is to do the same for competitors. To be competitive, a company must have an understanding of who and what its competitors are if it is to be competitive. This one-liner should identify their fundamental strengths and weaknesses. What does the competitor do, and how does it impact what the company does? Many have found this to be a challenging, but surprisingly effective, method for beginning the derivation of viable, and, it is hoped, successful models.

Don't forget, however, that no model can be expected to last for extended periods. As the high-technology world continues to unfold, the half-life of a business model shrinks continuously, and successful companies will have to find a way to embrace change and take advantage of it.

The Author

Jim Dudley leads strategic advisory engagements for Ernst & Young. He focuses on the petroleum downstream and related manufacturing and service businesses. Prior to joining Ernst & Young, he was the Senior Managing Director for Wright Killen & Co. He began his career with the forerunners of Unocal Corp. and ExxonMobil Corp. and holds a BS in chemical engineering and an MBA.