Flat Asia-Pacific markets to deflect Middle East products westward

Petroleum products from the Middle East are moving westward more and more frequently. This trend is likely to continue and even increase, because Middle East producers will face the choice of either exporting westward or running at low rates.

Product demand in the Middle East, which is easily unsettled by a variety of circumstances, is unpredictable from year to year.

Over the longer term, however, growth has occurred at a fairly steady rate, averaging increases in about the same increments annually. In the 2000-05 period, however, demand is likely to take a big jump based on chemical projects using naphtha and LPG.

But, because there is no certainty that these projects will come on stream, there is some doubt as to the level and timing of these demand increases. This uncertainty is magnified by the fact that some plants are being built with greatly enhanced feedstock flexibility.

Although many refining projects have been canceled, those now under construction and those few likely to be built lead toward a huge increase in products export potential from the Middle East-far in excess of the increases in domestic demand. The bulk of this capacity is already nearing completion.

Because most of the new capacity is either in the form of cracking refineries or condensate splitters, the products slate that will be available is sophisticated, with large amounts of middle distillates for export.

Unfortunately, the Asia-Pacific region's need for imports of such products has been sharply curtailed and shows little potential for recovery; indeed, because of new projects given the go-ahead in Asia, the outlook is even grimmer than it appeared to be a few months ago.

Although there are still markets for fairly low-specification products in Latin America, the volumes of surplus the Middle East refiners will have is too large to be absorbed without significant expansions in exports to North America and Europe. This means that, although there have been many upgrading projects undertaken in the Middle East for quality improvement, there probably will be a spate of additional specification-improvement projects undertaken in the next few years.

Historical Middle East demand

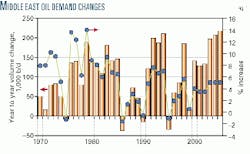

Growth in Middle East oil demand-entailing demand in the "Middle East Nine": Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Yemen-fluctuates far more widely each year than growth in Asia, as Fig. 1 illustrates. Much of this results from the relative size of their economies; the Asia-Pacific region has a more massive population, larger economies, and more countries than the Middle East.

The region also is proportionately more subject to political upheaval than Asia; i.e., turmoil in Iran is equivalent, in Asian terms, to turmoil in China and India simultaneously. The economies are linked to oil revenues, which makes economic growth and government finance inherently volatile.

Introduction of a single new industrial project can have a perceptible effect on the oil demand of the whole region, because most of the economies are relatively small. There are large unharnessed resources in these relatively small economies, so they can implement fuel-switching projects that move the bulk of a country's demand in one sector from, say, oil to gas, in just a few years.

Despite this inherent volatility, however, Middle East increases in oil demand have been remarkably steady when spread out over a number of years. The average increase in demand for 1970-2000 was 95,000 b/d each year. For 1980-2000, the annual average was 101,000 b/d; and for the decade of the 1990s, it was 105,000 b/d. In other words, Middle East oil demand historically has increased in increments of about 100,000 b/d, but it does so in jumps and spurts.

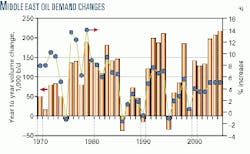

Some of the factors and events that affect Middle East growth are clearly visible in Fig. 2. In 1985, the oil price collapse curtailed demand growth, which resulted in slashed government spending, cuts in salaries, and negative gross domestic product growth.

In 1990-91, the Persian Gulf war caused stock builds on an emergency basis, followed by drops in demand as consuming facilities in Iraq and Kuwait were shut down (or in some cases, destroyed).

Iran and Saudi Arabia raised their low domestic oil product prices in 1995 for the first time. Other price increases have followed in both countries; in Iran it has been an annual affair.

Finally, in 1999, the Fujairah bunker market suddenly shrank-for reasons that still remain obscure.

In the Middle East, the regional market is small enough for such individual events to be seen in the overall total (Fig. 2).

New oil products demand

If one should draw a line across the top of the demand curve in Fig. 2 from 1973 to 2010, it would indicate that the general growth pattern has been almost a straight line, with substantial downward dips and a sudden acceleration after 2000.

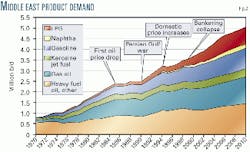

Yet, it can be argued that much of the Middle East's (projected) oil demand growth is seen as slowing down after 2000. These seemingly contradictory views are explained by the difference between traditional fuel demands and the emergence of new uses in greenfield industries now under development.

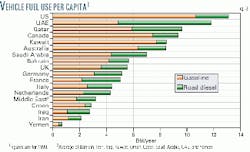

As Fig. 3 shows, in some Middle East countries, consumer transport fuel use per capita has already begun to approach, or even surpass, levels commonly seen in Organization for European Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Although in some Middle East countries there is still tremendous growth potential, in many of the richer states, per capita consumption has already reached high levels.

Coupled with natural gas substitution and continuing price increases in Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the use of oil for many traditional operations is leveling off or even-in a few cases-shrinking.

In 2000-05, annual increases in oil demand are projected to suddenly soar to 170,000 b/d each year, compared with the average 100,000 b/d increases of the past 30 years. But if naphtha and LPG are excluded, the annual increase tapers off to about 80,000 b/d of new demand each year. The difference is attributable to the third boom in petrochemical projects in the Middle East.

The Middle East countries experienced one colossal wave of petrochemical construction beginning in the late 1970s. This was development based on gas and ethane feedstocks, producing mainly ethylene and ammonia-urea.

A second boom was the construction of butane-based methyl tertiary butyl ether plants in the mid-1990s, which made Saudi Arabia and Dubai major exporters of oxygenates.

The new projects are more diverse. They include a continued focus on olefins but with plants using heavier feeds, mostly LPG but some naphtha as well. Many of these plants have high feed flexibility and can mix ethane, propane, butane, mixed LPGs, or naphtha as desired, depending on price and availability. There also is a new emphasis on aromatics-some from naphtha but a great deal of new production from LPG via UOP's Cyclar process.

These projects account for the apparent regional surge in demand; other than LPG and naphtha, growth is restrained. But these projects also introduce endless uncertainties into the demand forecast; cancellation or speedups of single plants can affect the regional outlook. In addition, the new penchant for feedstock flexibility introduces uncertainties in and of itself, as a plant may have very different feed consumption from year to year.

Refinery additions

Market conditions have slowed or derailed many of the overly ambitious plans for refinery additions in the Middle East, at least in the near term.

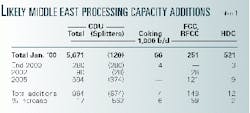

In the next 5 years, crude distillation unit (CDU) capacity is expected to expand by only 17% at most; the only large projects are in the UAE and Qatar. As Table 1 shows, 75% of all the new CDU capacity likely to come on stream before the end of 2005 is made up of condensate splitters in Qatar, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and possibly Iran. In terms of their impact on the output of light and middle distillates, use of condensate splitters is equivalent to fully upgrading a refinery of similar size.

In addition to this increase in condensate splitting, cracking is also set to increase substantially. Catalytic cracking will jump by almost 60% if planned projects for mid-decade are completed, the biggest increase coming from Oman's Sohar project, which is a zero-CDU refinery that will take long resids as the primary feedstock.

Between condensate splitting and cracking expansions, the equivalent sophistication of the Middle East refining system is taking a major jump forward. If Saudi Aramco decides to upgrade its Rabigh refinery, the increase in sophistication will be even greater than that shown here.

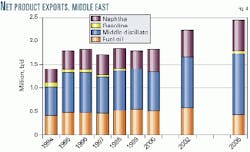

The effect of these changes (not including Rabigh, the configuration of which has not yet been decided) is shown in Fig. 4.

The increases in output, even under these scaled-back plans, still outpace the growth in regional demand and result in an increase in exportable surpluses.

More importantly, the cuts of the barrel hitting the export market will also undergo substantial changes. In 1999, net exports of products (excluding LPG) were two-thirds light and middle distillates and one-third fuel oil and other heavy products. By 2005, if present plans prevail, the light and middle distillates could make up 80% of the export barrel, and fuel oil exports would actually decrease. The Middle East has come a long way from the days when it was thought of primarily as a source of surplus fuel oil and naphtha.

On the face of it, this would seem to be a change for the better. Typically, the world tends to run short of light and middle distillates, while fuel oil and naphtha have often been a glut on the market. Extensive planning and billions of dollars have been devoted to investments in Middle East refining and upgrading to bring the output slate to one that produces far less than the traditional 40-55% fuel oil. The figure is now about 27%, and it is headed toward 23% or less in 2005.

Asian demand drop

Unfortunately, Asian demand for imports of these formerly desirable light and middle distillates (except for naphtha) has plunged to very low levels.

Taken together, gasoline, kerosine, jet fuel, and diesel imports into Asia were about 860,000 b/d net in 1995. By 1999, this figure had tumbled to about 140,000 b/d. Figures could drop further, to 120,000 b/d or less, in 2002.

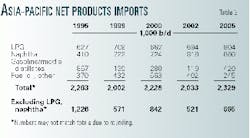

Table 2 shows net imports of refined products into the Asia-Pacific region in 1995 and 1999, with estimates for 2000, 2002, and 2005. Naphtha and LPG show continuing vigor throughout the period. Fuel oil peaks in 2000 and then will decline in 2005 to below the 1995 level. The "spec" fuels (gasoline and the middle distillates) experienced a general decline (with a slight revival in 2000) and, in 2005, will still be only about half of their 1995 level.

In general, total net imports into the region are relatively flat over the period, with downward wobbles in 1999 and 2002. When naphtha and LPG are excluded-much of this is supplied from gas processing in the Middle East rather than from refining-the picture is grim. Despite a brief peak in 2000 from fuel oil imports and delays in onstream dates for new refineries, the sag in imports is shown as improving only slightly; by 2005, net imports of products other than LPG and naphtha will still be only about half of their 1995 levels.

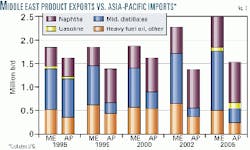

The dilemma this presents is shown in Fig. 5 (with LPG excluded). In 1995 the Middle East exports were a good match to Asian import needs (with a little fuel oil left to export west). By 1999 Middle East output has risen only slightly, but Asian imports had decreased significantly.

This year provides a lull, with some recovery in Asian imports and little increase in Middle East exports; but even now, the Middle East has a significant surplus of middle distillates that have to move to the Atlantic Basin. The situation will only worsen in 2002. And 2005 figures show increased import needs but also increased export potential for the Middle East, with the East-of-Suez surplus remaining about the same.

Movement to the west

Middle East products are already moving westward. Middle East suppliers have been pushing into East Africa for the last decade, and both Saudi Aramco and Kuwait Petroleum International are now suppliers of jet fuel on a global basis.

But the current situation has pushed Middle East exporters into markets that are far beyond previous frontiers; Middle East suppliers now contest traditional European exports to West Africa, and Latin America is now an important outlet for Middle East production.

For the time being, Latin America provides one of the few remaining markets where specifications are relatively lax, but the capacity of Latin America to absorb imports has limits. Western OECD markets offer larger opportunities in the longer term, but the specifications are stringent and are being tightened further.

Middle East refiners have been aware of the problem of tightening specs for some time, particularly tighter sulfur specs, and many upgrading projects are under way or have been completed, specifically for quality improvements.

Nonetheless, the quality hurdles that were anticipated were far lower than those presented by the emerging North American and European markets. As it becomes clear that Asian demand will not absorb much of incremental Middle East output, more refinery upgrade projects will certainly be launched. It is also likely that Middle East producers will push further downstream by orienting their refineries toward integration with the petrochemical industry to develop captive demand in their home countries.

The Middle East has long been the fulcrum between East and West in the crude market. The forced expansion into the Atlantic product markets will probably, in the longer term, lead to the Middle East becoming the arbitrage refining center between East and West as well. This was actually part of the Saudi concept when they launched their export refining drive back in the late 1970s; their avowed plan was called "40:40:20," that is, 40% of product exports to Asia, 40% to Europe, and 20% to North America.

Sometime late in this decade, that goal may be achieved, although no longer as a matter of planning but rather as a matter of circumstance.

The authors

David T. Isaak is vice-president of Fesharaki Associates Consulting and Technical Services Inc. (FACTS Inc.) and of East West Consultants International Ltd. His research focus is on computer modeling of energy systems, with emphasis on downstream hydrocarbon processing and transportation. Most of his work has been on the Middle East and Asia-Pacific regions. Issak received his MA and PhD in geography from the University of Hawaii, with theses on the world tanker market the Middle East petrochemical industry. Undergraduate work in physics and chemistry led to a photophysical chemistry research fellowship at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. He has coauthored three books and written numerous papers. He also has served as adviser to more than 30 governments worldwide.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc. Born in Iran, he received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran. He joined the East-West Center in 1979 and currently is a senior fellow and head of the Energy Project at the East-West Center. His area of specialization is oil and gas market analysis and the downstream petroleum sector, with special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region, Middle East, Latin America, and US. He is an adviser to numerous oil and gas and other energy companies, private and state-owned, and to governments in the Middle East, Pacific Basin, and Latin America, as well as to the US government.