COMMENT: Is Shell Report 2000's sustainable development focus an anomaly or sign of the future?

A sea change is occurring in the way that petroleum companies report results.

No longer are annual reports merely the province of financial and operating data. Increasingly, they cover initiatives in the areas of social responsibility and health, safety, and the environment (HS&E).

While discussion of such initiatives long has been included in annual reports, it was usually relegated to pages near the back. But the revival of activist environmentalism in the 1990s increased the importance to companies of communicating their HS&E efforts to the public. Consequently, some companies now issue separate reports focusing on such issues as environmental concerns and social responsibility.

Shell Report 2000

Royal Dutch/Shell has taken the communications effort to a new level with its latest annual report, Shell Report 2000 (SR2000). Shell pioneered the concept of issuing a separate report on its activities in support of sustainable development and then seeking to measure progress. SR2000 not only covers sustainable development, it makes related efforts the dominant features.

The document is remarkable as much for what it leaves out as for what it puts in. Readers interested in detail about, say, exploration results, must look elsewhere. Beyond a snippet, there is almost nothing on operating results. There is a bit of discussion about financial results and how they compare with those of Shell's peers. But everything about operating and financial results in SR2000 is couched in the context of Shell's commitment to and performance on sustainable development.

Each of the operating segments is viewed through this prism and its performance judged accordingly. And the company has taken pains to devise a comprehensive series of measurements by which to gauge its HS&E performance, creating quantifiable parameters it calls "key performance indicators" (KPIs) and then implementing ways to verify those parameters (see table). The latter involved verification of 25 parameters and visits to 40 operating units around the world. It then focused on the 12 HS&E parameters that Shell and the verifiers believe have the most significant impacts at the corporate level.

Shell then attempted the same effort with social responsibility performance, although it and the verifiers acknowledged a lack of generally accepted standards for reporting or verifying such things. The verifiers, KPMG Accountants NV, The Hague, and PricewaterhouseCoopers, London, instead concluded, "We have adopted a verification approach that reflects emerging best practice, using a framework based on the principles underpinning international standards on financial auditing and reporting."

Shell sees the KPIs as the logical basis for that verification effort: "Our ultimate ambition is to achieve a level of public trust and respect that will reduce the need for formal verification.

"This might be some years away, but we hope that widespread efforts to build better relationships between companies and civil society will lead to the emergence of trust through alliances and greater involvement."

Good business strategy?

Shell believes that incorporating values of sustainable development makes good business sense.

It defines "sustainable development" as the world's approach to tackling some of society's most pressing concerns-extremes of poverty and wealth, population growth, abuses of human rights, environmental destruction, climate change, and loss of biodiversity.

"Our success as an organization is intimately linked to that of society," Shell said in SR2000. "We wish to play our part responsibly-by maintaining and enhancing natural and social capital, as well as contributing to the global economy's capacity to generate and distribute wealth."

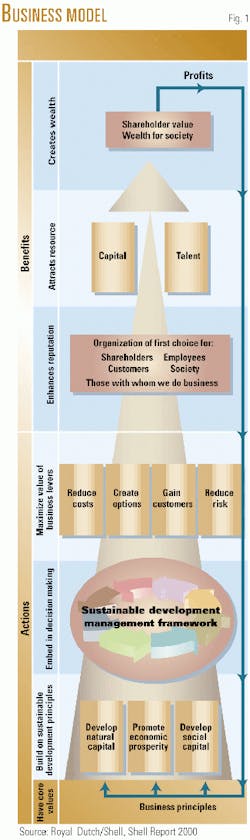

It says sustainable development "provides the best model to see these elements together in an integrated way while creating business value (Fig. 1)."

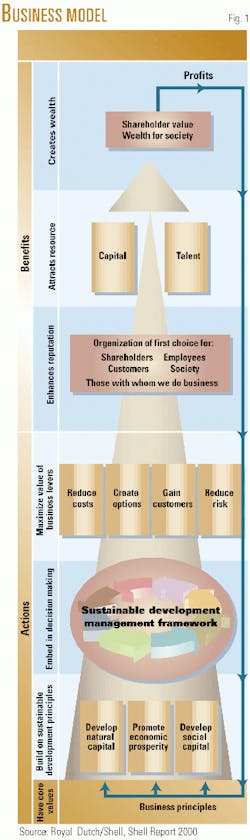

Shell has designed a sustainable development management framework (SDMF) to help it "achieve the necessary integration and create the conditions for building long-term value and a strong brand in line with our business principles and society's expectations (Fig. 2)."

A key driver of the SDMF is engagement, but Shell also seeks to derive value through implementing four key levers:

- Reducing costs. In the short term, this would be achieved by becoming more environmentally efficient-which Shell defines as doing more with less-and, in the long term, by working with others to eliminate waste.

- Creating options. This would come about by anticipating new markets "driven by people who want a more sustainable world" and spurring the evolution of business portfolios and supply-chain relationships to match."

- Gaining customers. This would result from Shell enhancing its brand by providing services and products built on "sustainability thinking" to create customer loyalty and market share.

- Reducing risk. Here, Shell would manage risks better by understanding what represents responsible behavior. It proposes to focus on "managing existing assets in the short term and evolving the business portfolio longer term" and thus garner recognition from financial institutions for success in this area.

"We believe that matching these levers to the strengths of our businesses, in ways that show commitment and responsible performance, will enhance our reputation and, in turn, attract and retain talent and capital.

"By these actions-which are aligned with and support the wider conditions required for sustainable development-we will generate short, medium, and long-term financial value, not just for shareholders but for society at large."

To implement this strategy, Shell has outlined a "road map" to guide its actions and for stakeholders to chart its progress (Fig. 3). The company then devotes the bulk of SR2000 to presentations of its performance to date under this sustainable development strategy across each operating unit, tracking that performance according to KPI data changes and inviting stakeholders to provide feedback via a variety of media.

In the operations section of SR2000, each operating unit subsection-including separate subsections on renewables and downstream gas-and-power units-carries sidebars highlighting specific initiatives on HS&E and social responsibility issues, from projects promoting biodiversity in Peru's rainforest to progress on diversity in executive staff makeup.

Such initiatives and such transparency are crucial to its future business success, Shell claims, even if the goals outlined seem fuzzy for a constituency more accustomed to gauging performance on reserves additions and retail market share gains.

As put by Mark Moody-Stuart, chairman of Shell's committee of managing directors, "I know that many who work at the sharp end of Shell companies-on the rigs, in the chemical plants, and on the forecourts-still find it difficult to understand what this means to them and how they can best contributeellipseThe changes to how we take decisions is part of the answer-for example, making it clear that, for project proposals to succeed, they must take into account environmental and social considerations as well as financial ones.

"Visible, clear leadership and support are essential. I am determined that we shall accelerate the drive to make sustainable development part of our culture and continue to meet the promise to live up to our business principles."

Some conclusions

Some cynics on both ends of the political spectrum might see Shell's bold departure from the norm in such an extreme emphasis of HS&E and social responsibility issues as a public relations response to controversies over disposal of the Brent spar and activities in Nigeria.

But close observers of Shell have said the company's reaction to those crises was not that they were temporary unpleasantries to be weathered but truly corporate culture-altering events that shook the staid old giant to its core.

In the broader context of long-term strategy, Shell has thus far not merged with another giant-as competitors British Petroleum PLC and Exxon Corp. have with, respectively, Amoco Corp. (plus ARCO later) and Mobil Corp.-to form a new breed of supermajor. The competitive pressure has intensified with the middle tier of major integrated companies joining together, such as Total SA with Fina SA and Elf Aquitaine SA to form TotalFinaElf SA, and Repsol SA with YPF SA to create Repsol-YPF SA. More recently, Chevron Corp. and Texaco Inc. have agreed to merge.

Some market analysts have, in recent years, faulted Shell for lagging behind its chief competitors in shareholder returns. This criticism intensified when the new supermajors suddenly burst upon the scene in the past 2 years. SR2000 thus makes repeated reference to new measurements for shareholder return and company performance that focus on sustainable development-while proceeding to gauge Shell's performance against those measurements. Shell seems to be attempting to stake out new territory here, proclaiming the efforts to be integral to a sound business strategy in a new world order. Through that prism, SR2000 can be seen as both a response to the megamerger trend and an assertion that a company's role in the social order, not just its size, is now central to competition.

How well Shell succeeds in this strategy may be reflected in the larger business world's efforts to market "green" and other politically correct themes. There is certainly a niche for such opportunities, but what happens when some of the world's largest and most powerful industrial companies reposition-indeed, even redefine-themselves in the context of sustainable development? Certainly BP is in this same camp, with its rebranding and corporate re-identification with the Helios logo and the slogan that positions its initials as representing "Beyond Petroleum." And the in-house publications of other Europe-based firms, such as TotalFinaElf and Statoil SA, are replete with similar sentiments.

Such repositioning and re-identification campaigns seem to be gaining acceptance among European companies, where promotion of the sustainable development ethos has been more politically entrenched than anywhere else in the world. That can be seen in Shell's and BP's embrace of the principle of ultimately moving away from high carbon-content fuels such as coal and oil as part of an effort to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. Such an embrace has generally been rejected by the US-based majors, many of whom still vigorously contest what they see as a less-than-rigorous application of scientific principles by the alarmists on climate change theory.

Is this growing schism just another reflection of the difference in corporate cultures of US and European companies? Does it more accurately reflect company-specific reactions to developments whose scope is unique to Europe?

Or are the European-based majors, in fact, instituting such campaigns as a warning shot across the bow of rivals about what constitutes the best business strategy in the new millennium?

John D. Rockefeller eliminated his rivals by oversupplying the market and undercutting them on prices-in his words, giving them "a good sweating." Will Shell and BP do the same with what is, at first glance, a business strategy based on altruism?