Balance needed in operating agreements as industry's center of gravity shifts to state oil firms

The oil and gas business has undergone a fundamental shift in industry structure in recent years. Peter A. Davies, chief economist at BP, recently observed: "The most remarkable characteristic relating to the oil industry is probably the fact that its industrial structure remained largely intact for some 70 years or so, despite a wide range of global changes in markets, geopolitics, and technology. This period of constancy appears to have come to an abrupt end during 1998-99."

As the economic forces driving this change continue, the industry as we have known it will become less and less recognizable.

Four main factors account for the change:

- The increasing difficulty of finding new reserves to replace declining production from mature producing areas.

- The concentration of worldwide reserves in a handful of state-owned companies and their gradual emergence as viable competitors-both as newly privatized entities and as expanding government operations.

- The spread of technology to developing countries.

- Deregulation of energy markets, with the resulting competitive pressure on prices and the integration with other energy commodities, particularly electricity.

There are some predictable consequences as these changes continue and quicken. One is that large integrated oil companies (majors) that have for many years served as operators on large projects will much more frequently be nonoperators on large international projects.

In that circumstance, they should be keenly interested in seeing that the operator-oriented Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) so widely used in their domestic projects does not become the standard governance vehicle for their international projects.

At present, the Joint International Operating Agreement (JIOA) adopts many of the JOA's operator-favoring provisions. Looking forward, we believe even majors will be better served by a revised JIOA that is more balanced.

Economic forces at work today

Perhaps the most obvious change in the oil and gas industry in recent years has been the flurry of mergers among the industry's largest firms. The past 3 years have witnessed the marriages of Amoco Corp. and Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) to British Petroleum Co. PLC (BP); Mobil Corp. to Exxon Corp.; and Petrofina SA and Elf Aquitaine SA to Total SA. Smaller mergers occurred between regional subsidiaries of Shell Oil Co. and Texaco Inc. and between Ashland Oil Co. and Marathon Oil Co.

The primary rationales for these combinations have been the desire to reduce costs and increase capital.

For the most part, these firms represent the historically dominant integrated firms. Along with consolidations, many have shed activities such as chemicals, coal, and minerals mining, and even downstream activities such as refining and gasoline retailing.

Clearly, such firms see the future of oil and gas exploration and production as one that will require focus and low costs to assure competitive viability.

They are right to adopt that belief. Exploration for oil and gas reserves has in recent years turned to ever more remote and costly locales. After more than a century of worldwide exploration, most of the low-cost fields have been discovered, and many are largely depleted.

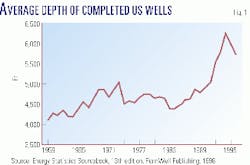

New, more-expensive production areas must replace mature fields. Today, wells are drilled in ever more difficult and inaccessible areas. Wells are deeper than a generation ago, and the cost of finding large, new reserves is rising accordingly. These trends can be seen in a gradual but long-term increase in US drilling depth and a sharper rise in US drilling costs over the last 6-7 decades (Fig. 1).

Technological advances, particularly 3D seismic imaging and horizontal drilling, have somewhat reduced cost and risk for any given well, but the overall trend is toward larger, deeper, and more-expensive projects (Fig. 2). Moreover, for US-based companies, the shift to exploration and marketing overseas means increased political risk.

In today's energy world, E&P companies compete with a growing number of newly privatized entities and government-controlled enterprises. In addition, prices and margins will be set in an international market that quickly incorporates and reflects supply additions and demand shocks, not only for oil and gas but also for related energy products such as electricity.

In that environment, not only must overhead costs be held to a minimum, but the consequence of errors will be magnified. Companies with large, expensive projects that fail to achieve expected reserve or cost targets will be penalized.

Increases in depth and finding cost, political risks, and competitive pricing all serve to make joint operations among several firms on a single project more attractive. Such joint operations serve to spread those risks and thereby reduce the impact of errors on any individual participant.

Such risk-sharing can only be accomplished, however, if the terms under which joint operations are carried out reflect a mutual, predictable balancing of obligations and rewards for the participants.

Domination of world reserves

A second key fact governing today's oil business is that non-US companies control the bulk of the world's known oil and gas reserves.

In the early days of the industry, US companies and a handful of European rivals explored and developed the world's oil fields. Many of the largest oil fields were developed through government concessions that brought the world's largest oil companies into cooperative ventures.

As host companies and governments prospered and matured, they became more sophisticated partners. The duration of large concessions generally has shrunk while the host country's share of production has risen, signs of the industry's gradually increasing competitiveness.

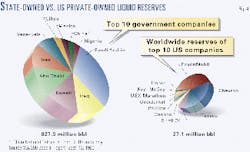

Today, 20 non-US companies control 87% of the world's proved reserves. When reserves held by US companies are considered, only 2-ExxonMobil Corp. and Chevron Corp-would make this top-20 list, and they would rank 12th and 19th, respectively (Fig. 3).

Moreover, these rankings vastly overstate the relative importance of US companies in the global reserves picture. The distribution of reserves among the top 20 companies is highly skewed toward the top. Saudi Arabian Oil Co. (Saudi Aramco) alone owns over 25% of world reserves, and together with Iraq, 36%. The top 5 companies, all state oil companies, own 63%.

The reserves of ExxonMobil, invariably among the largest corporations in the Fortune 500 (last year, No. 4), are not even 1/25th those of Saudi Aramco's reserves (10.9 billion bbl compared with Saudi Aramco's stratospheric 259 billion bbl). ExxonMobil's holdings are 1% of world reserves; the 11 companies that rank before it, all state companies, hold 81% of world reserves.

Even these stark figures understate the tilt away from US control because they exclude Russia's vast unproven reserves.

Fig. 3 shows at left the relative share of the top 20 non-US companies' liquids reserves (oil and NGL), and on the right, the holdings of the 3 US companies that would rank among these companies.

The difference is just as stark when comparing the 10 largest government entities and 10 largest private US companies (Fig. 4). Against this backdrop, US reserves have been declining, if gradually, over the last few decades.

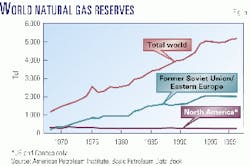

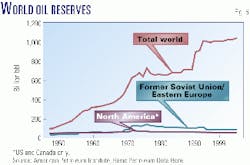

In contrast, world reserves have jumped sharply. Looking at natural gas, for instance, overseas reserves have grown sharply since the energy crises of the 1970s (Fig. 5, p. 77).

The story of US decline, and world increase, is even more pronounced in oil (Fig. 6, p. 78).

A striking fact about this dominance of world reserves by state-owned companies is that virtually none of them have become true players in world oil markets. The few national oil companies that play a major role outside their own countries are exceptions.

State-owned companies generally were formed to maximize revenues from state-owned resources and traditionally have not tried to become active competitors in world markets.

Yet it surely is only a matter of time before companies that manage production of so much wealth set their sights on the international business as well. With their vast reserves, they can easily afford to develop the necessary skills and expertise.

With finite producing horizons in their own reserves, they need to develop international operating expertise to survive and grow. In a world of increasingly mobile know-how as well as capital, some of these companies will probably become effective competitors in the years ahead.

Some companies also may be driven by necessity. For instance, of the list of state-owned companies, India and China are net importers of oil. It is no accident that they have sent the two largest groups of graduate students to the University of Texas Petroleum Engineering program in recent years.

These two countries have a strong incentive to develop a firm operating base because they must draw on foreign fields to serve their huge populations, and they will for the foreseeable future. Each step either takes to industrialize will only increase its energy needs and the likelihood that internal demand will continue to outpace domestic reserves.

Technology, expertise spreading

It is a source of great risk and uncertainty that the large traditional oil companies hold legal claims to only a tiny fraction of the reserves they need to stay in business. These companies traditionally have been able to exploit much of this wealth without owning it via a variety of concession agreements.

Yet it is inevitable that producing countries will ask why they can't rent or buy this expertise, paying a fee for modern technology and expertise rather than ceding control over their resources to outsiders.

Historically, established companies are hardly in a position to refuse. While they have a vast intellectual capital, it is capital with a peculiar limitation: it has no value unless applied in the exploration and production of oil and gas. It is not at all clear that US companies can continue to dominate markets for another generation without transferring skills and intellectual capital.

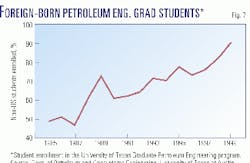

One can already find evidence of an international transfer of skill through another path: the education of the next generation's industry experts. Here, the US is exporting its technological lead in the oil and gas business.

At the University of Texas, the percentages of enrollment by non-US students in the graduate petroleum engineering program for the fall semester are as follows: 77% in 1997, 83% in 1998, and 81% in 1999 (Fig. 7, p. 79). Long-term figures for the Texas program show a stark increase in the last 15 years:

India provides the second largest contingent of these Texas graduate students, after US nationals, followed generally by China and then Taiwan.1

Similarly, in the Petroleum Engineering Department at Texas A&M University, 81% of the graduate students (83 of 103) were foreign nationals in 1997-98; 80% in 1998-99 (81 of 101), and 82% in 1999-2000 (113 of 138).2

The fact that the repositories of the US technological lead in the oil and gas industry are distributing their knowledge mainly to foreign nationals can only increase the likelihood that some state-owned companies will come to the fore within the next few decades.

The traditional oil companies thus far have counterbalanced weak reserve positions by their high level of skill and their ability to generate capital. Given the right incentives, these companies can find the money and have the skills to develop very large fields at their own risk.

But the fact that US companies own so little of their most vital resource suggests that, if they want to spread their risk and continue to participate in major developments worldwide, they are going to become nonoperators on projects with foreign operators more often than in the past.

Deregulation and privatization

It is important to understand the cultural and structural shift embodied in the last decade's wave of privatization and deregulation.

Country by country, large oil nations are opening their markets to competition, and many have already released state-owned firms into the private market.

Some formerly state-owned companies may become wholly or partially owned by management previously involved with large international companies. Some will be launched directly into the market.

If only a small percentage of these firms becomes viable competitors, they will produce a new level of international competition. And as these companies win operating positions in projects that would in the past have been handled by longer-established companies, traditional companies that want to participate will have to take more nonoperating positions.

JIOAs should reflect changes

These economic changes have legal consequences.

New E&P projects in this rapidly changing market still will be heavily influenced by long-established US legal forms. The majority of joint investments in the domestic US industry use a single form, the JOA. Many large companies now are trying to make the JIOA, which is based on the JOA, the new standard for international deals.

Bargaining occurs within a limited range of "feasible" options. A deal's outer limits are determined by the parties' perceptions of fairness as well as their alternatives. Industry forms set benchmarks, both for fairness and for accepted practice. As such, they serve to structure and direct negotiations.

Using balanced standard forms to bolster the legitimacy of predefined legal structures will be more important for companies that cannot reasonably expect to retain a dominant economic position as operators.

For that reason, such companies should examine the JIOA closely to assure that it represents the best possible governance vehicle for spreading project risks and sharing rewards. While the JIOA facilitates joint operations in many ways, it also exhibits a pronounced tilt in favor of the company designated as project operator.

The international industry presents established firms with two challenges. First, they must win approval for a standard investment form that tracks their general expectations and experience. This is largely why the JOA has been so popular domestically.

Second, they should pay particular attention to the nonoperator position if they are more likely to assume that role in the future.

Economic functions, shared purposes

Companies use contracts such as the JOA and JIOA, rather than handling their investments internally, when they expect outside contracting to be more efficient and when they expect to gain from shared managerial skills and information or the pooling of physical and financial assets.

The frequency of JOA operations shows that most US companies, even majors, often see advantages in joint operations. Joint operations allow each participating company to contribute its specialization while sharing other companies' expertise in other areas. They pool risks and resources, expand the range of operations, and achieve economies of scale. Having common standards can facilitate learning and reduce transaction, negotiating, and supervision costs.

Joint operations also can rationalize a patchwork of competitive leaseholdings when unitization is undesirable or not available.

All these benefits are reasons to expect joint operations to yield substantial savings.

The provisions of the JOA and JIOA can be divided into three parts: those that benefit all parties, those that benefit some but not others where the source of the benefit is not tied to operator-status, and those that favor only the operator.

One set of terms establishes common procedures needed for any joint project, and it benefits both sides. These terms cover everything from the designation of operator to procedures for consenting to completion, sidetracking, and subsequent wells; the duty to maintain accounting records; establishment of an audit mechanism; agreement on a voting procedure; default provisions; billing and payment timetables; budget provisions; and provision of access to the well site and to information.

Other provisions affect venture partners differently, but the differences do not consistently break along operator and nonoperator lines.

Examples are nonconsent provisions, defaults, preferential purchase rights, and AMIs (areas of mutual interest). The importance of each depends upon a party's anticipated future conduct. Parties who believe they might default or go nonconsent want the smallest nonconsent penalties.Those expecting to sell their interests will not want preferential purchase rights that can hamper their ability to attract other buyers and limit the market value of their interest. Those who own or expect to own nearby acreage will not want an AMI.

In contrast, in the areas discussed next, the interests of operator and nonoperator diverge sharply. We examine the JOA because it is the predecessor to the JIOA.

Operator-favoring terms

Large operating companies, including majors, have dominated the committees that draft standard forms. Presumably as a result, a number of terms reflect their interests.3

For instance, the standard JOA fails to say that the operator is neither to gain nor lose by joint operations, even though that is its underlying accounting basis.4 This omission gives operators wider latitude to try to justify special deals.

In a related failure-of-accounting-precision example, the JOA does not expressly force the operator to share the benefits of such practices as discounts, delay payments, and equipment buybacks. Sharing such benefits as well as costs is one of the guiding purposes of the JOA, but it is not stated explicitly.

The JOA does not require the operator to disclose to its partners in advance if it expects to collect a separate profit (and if so, how much). Operators naturally prefer to earn high separate profits, while nonoperators want to maximize joint returns.

Recent disputes over posted oil prices and deregulated gas services show that current legal standards have not been precise enough to make everyone's dollar stake "transparent," as they should be in a balanced, efficient contract.

Operators do not have to disclose in advance the fact or terms of affiliate use, an area that has seen much controversy. And operators have blocked a requirement that they escrow or otherwise not commingle nonoperator funds.5

Information is another key area. The operator's control over drilling and development means that it generates the scientific knowledge created by joint operation. Much of this work is funded by the joint account, through overhead charges and certain direct charges.

The JOA gives nonoperators the right of access to operator's books and records and to the contract area but not to any "geologic or geophysical data of an interpretive nature" unless its "cost of preparation" was charged to the joint account.

Such direct costs of preparation will not encompass many ways that nonoperators pay their proportionate share for the operator's infrastructure. Yet the JOA does not clearly address the potentially acute conflict of interest when joint information is packaged in what the operator views as proprietary know-how.

Another provision that favors operators is the JOA's removal provision, which only allows nonoperators to remove the operator for "good cause," and then only upon majority vote. Good cause is defined as including material breaches of the JOA as well as gross negligence or willful misconduct. But JOA drafters rejected a provision that would have let nonoperators impose removal without cause by a certain percentage vote.6

In a pronounced tilt favoring operators, the JOA tries to disclaim fiduciary duties and limits operator liability to gross negligence and willful misconduct.

The industry has sought such terms because courts so often have found that the operator is a fiduciary, be it on a joint venture or mining partner theory, on a trust-like theory, or under special rules for unit operators and grubstake holders.

Other operators are fiduciaries because they entered into formal partnerships or because they have long-standing relationships of trust and confidence with their partners. The disclaimer and exculpatory clauses try to lower the standard of care that courts otherwise might apply to joint operations.7

JIOA favors operators

Although the JIOA has a more flexible structure than the JOA, it retains the JOA's operator-favoring bent.7

In one healthy change, the JIOA does mandate an operating committee. The operator still has "exclusive charge" and "conduct" of operations, but the operating committee of party representatives is to provide "overall supervision and direction of Joint Operations."

It is true that an operating committee might become just a more convenient way for an operator with far-flung partners to get consent. But the language seems to picture a stronger role.

There is some improvement in the general accounting standard. The JIOA mandates that the operator shall "neither gain a profit nor suffer a loss" as a result of running joint operations.

This declaration, however, is immediately qualified that the operator can rely upon operating committee approval "of specific accounting practices." A stronger JIOA would establish an affirmative duty for the operator to disclose where it is making a profit and what it earns (a flat fee, a percentage, a rebate) and to have each charge approved in advance.

Otherwise, an operator could disclose a set charge but not the fact that it contains a markup. The committee might approve on the assumption that the operator is just covering costs, only to have the operator later argue that the committee had blessed the markup by approving the set charge.

Again without disclosure, an operator could try to use committee approval of affiliate use to immunize undisclosed profit-making through related companies and on general accounting principles to shield practices that give them a separate profit.

The JIOA makes it easy to do so by not requiring them to disclose their sources of profits on the venture. Nor does it require any special disclosure about affiliates and the profits they generate for the operator.

The JIOA addresses, but does not resolve, another key accounting issue, commingling. Instead, it offers a range of options. The first provision is the one that operators prefer, namely, that they can commingle.

The JIOA tries to solve the possibility of these funds being lost in bankruptcy by providing that they not be deemed operator funds; nevertheless, it does not prohibit the operator from mixing them with its own money. The lack of an escrow means that a bankrupt operator may have spent the money.

Other options let the nonoperators ask the operator to segregate joint account funds, or funds from the parties in each exploration area. A final alternative flatly states that the operator may not commingle.

The problem with this smorgasbord of options that range from no duty to a strict duty is that it does not legitimize any particular standard. The JIOA points out an issue, here the importance of separate venture funds, and pushes the parties to address it. But this is not enough to establish a viable standard.

By not providing an approved solution, the JIOA misses the opportunity to impose tested standards on parties new to the industry.

The JIOA's drafters may have believed that the JIOA needed options because its very looseness would make it easier to persuade parties from different backgrounds to accept the contract as a starting place for negotiations. But the cost of this flexibility is to reduce the JIOA's ability to center the international industry around a single set of standards.

Other JIOA options range from the amount of mandatory detail on Authorizations for Expenditures (AFEs) and cost estimating-and the effect of the AFE-to the degree of budgeting and contract details and the grounds for removing an operator.

Each of these squanders a valuable chance to establish an international industry standard. Such standards may be relatively less important among companies that share the same general practices and understandings, but they become more important where traditional oil companies enter into international projects with partners relatively new to the business or operate in very different business climates.

A US major in the nonoperator position, for instance, will not be able to point to the JIOA's escrow options-or any other part of the JIOA that merely lists options-to persuade a state-owned company or foreign government to adopt a particular standard.

The JIOA has a somewhat stronger duty to disclose information than does the JOA.

When disputes arise in this area, ordinarily the operating company is claiming that its analysis of drilling results or other work reflects its proprietary processes.

Operators generally will produce logs, cores, and other raw data acquired from a well. Many balk at relinquishing their own analysis of data, however, even though their partners may be paying for the labor embedded in that analysis and may have helped fund the training and experience of those making the analysis.

Among other things, the JIOA gives nonoperators the right to all "final geological and geophysical maps and reports." It does not expressly address reserve reports or analyses, and the limit to "final" work invites disputes.

Moreover, the JIOA excludes "proprietary" data from disclosure, unless the joint account has paid for developing the technology. That language does not address a gray area where the operator tries to shield its analysis of joint property by arguing that it is so intertwined with proprietary data that all analysis (in contrast with raw data) must stay confidential.

The operator and nonoperator have different interests about operator removal. The conflict centers on removal without cause.

The JIOA retains the JOA's automatic removal for events such as bankruptcy, but it leaves without-cause removal a mere option for debate. And, if nonoperators do want the overall check of removal without cause, the JIOA makes no recommendation on the voting percentage required to remove an operator.

Thus the form does nothing to set an industry standard in a provision that is critical to protect nonoperators. Removal without cause is a key veto. It gives nonoperators general leverage even where the JIOA doesn't grant specific power. Retaining general control becomes more important when doing business with operators who hale from different cultures and carry different expectations.

Another key term is the voting "passmark," the votes required to approve all decisions not having a more specific voting procedure. Having some voting procedure benefits both sides.

The voting levels, however, set the balance of power between operator and nonoperator on all affected items. Here again, the JIOA is silent on the best or recommended practice. It leaves the parties to select the passmark.

Then, finally, are the disclaimers. The JIOA removes the basis for holding foreign operators to a high duty of fidelity because it has even more comprehensive disclaimers than the JOA.

The JIOA tries to disavow fiduciary liability in every way possible. It states that liability is individual, not joint; that the parties do not intend to create a partnership or joint venture or other trust relation, and that, in their "relations with each other," they are not to be considered fiduciaries.

The JIOA broadens the JOA's ban of operator liability for anything less than gross negligence by making operators absolutely immune even for gross negligence in many cases (and if the operator is not liable as "operator," all parties pick up the costs in their proportionate ownership interests).

Parties are given an option to retain liability for gross negligence of only certain "senior supervisory personnel." The JIOA hedges again by offering a variety of damage-limiting options, starting at full liability for actual damage for repairs but also suggesting a set dollar limit on the operator's liability qua operator.

Thus the JIOA gives operators a triple exemption.

Not only does it maintain that they will not be treated as fiduciaries or partners, but it limits their contract liability to the gross negligence of certain officers at most and allows operators to pay only a fraction of the damage their gross negligence causes.

Needless to say, such clauses remove any force the JIOA might have to hold a foreign operator to a high level of fidelity. The standard is well below the duty ordinarily imposed on parties handling others' funds and property.

Better balance needed

If the new economic environment in which oil and gas exploration is conducted causes traditional industry companies to find themselves frequently in the nonoperating role, particularly when teamed with operators from other cultures that are accustomed to other legal systems, their self-interest should make them think twice about leaving these operator-favoring clauses in the JIOA.

Among the clauses that should concern these companies are the ones discussed in this article. They should promote a form that prevents the operator from making extra profits on investment funds.

They should have a right to full disclosure of affiliate economics. They should be sure their funds are segregated from those on other projects. They should have clear AFE and budget information.

They should have a clearer right to the geologic and reserve information they fund. They should give careful thought to the powers of removing operators without cause. And they should reform the disclaimer clause so that their operator will have the same high standards that ordinarily apply to a party handling the funds and property of another.

Although these have not been typical concerns of large oil industry companies in the past, they will become more pressing as the economic center of the oil business shifts.

References

- Hewett, Shelly, Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering, University of Texas at Austin.

- Blasinger, Tom, Department of Petroleum Engineering, Texas A&M University; Holditch, Steve, McAdams Professor.

- Boigon, Howard, "The Joint Operating Agreement in a Hostile Environment," 38 Inst. Oil & Gas Law & Taxation, pp. 5-1, 5-3, 1987; cf. Kennedy, C.M. "Joint Venture Accounting a la Copas-1962," National. Inst. of Petroleum Landmen 157, 1964; cf. Bledsoe, Robert, "Current Problems Between Operators and Nonoperators in Operating Agreements," 40 Inst. Oil & Gas Law & Taxation, pp. 8-1, 8-3, 1989; Cunningham, "Oil and Gas Accounting Procedure as Viewed by a Joint Interest Operating Director," 13 Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Inst., pp. 397-98, 1967.

- Jolly, John; & Buck, Jim, "Joint Interest Accounting: Petroleum Industry Practice" p. 2-3, 1988.

- McArthur, John Burritt, "Twelve Steps Copas Should Have Taken to Improve Oil and Gas Accounting Protections," 49 SMU Law Review, pp. 1447, 1476 n.64, 1996.

- Derman, Andrew, "The New and Improved 1989 Joint Operating Agreement: A Working Manual," pp. 59-63, 1991.

- There is disagreement over whether a blanket disclaimer of fiduciary obligations is enforceable. Compare, e.g., Lane, Christopher and Boggs, Catherine, "Duties of Operator or Manager to its Joint Venturers," 29 Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Inst., p. 99, 1983; Keefe, William, "The Oil and Gas Joint Operating Agreement: Unraveling Some Knots," 36 Rocky Mountain. Mineral Law Inst., p. 18-1, 18-12 n. 34, 1990; Martin, Patrick, "The Joint Operating Agreement-An Unsettled Relationship?" SWLF Special Inst., 1997.

The authors

John B. McArthur is a partner with the firm of Hosie, Frost, Large & McArthur in San Francisco. He has authored a number of articles dealing with legal issues in the energy industry. McArthur received a BA in sociology from Brown University, an MA in economics at the University of Connecticut, and his JD at the University of Texas (Austin). He also earned an MPA from Harvard University and currently is a candidate in the PhD program at the University of California.

Jeffrey J. Leitzinger is cofounder and president of econONE, which specializes in the economics of markets, competitive analysis, and regulation. He has over 20 years of experience in economic research and consulting, including 8 years with National Economic Research Associates. He has a BS in economics from Santa Clara University and an MA and PhD from the University of California at Los Angeles. Leitzinger has taught economics at UCLA and California State University in Northridge and has furnished expert testimony on the results of his research to numerous regulatory agencies, utilities, senior management, and other groups

Roger Ridlehoover is senior economist with econONE in Los Angeles. He has 16 years of experience in economic research, primarily as related to natural gas regulation, antitrust, and contracting. He has appeared as an expert economist in California, Texas, and Montana courts and serves as president of the Los Angeles chapter of the International Association for Energy Economics. Ridlehoover received a BS (magna cum laude) in economics from Texas A&M University and an MA from the University of California at Los Angeles, where he currently is completing requirements for a PhD in economics.