Brazil's petroleum prospects bright after successful demonopolization beginning

Five years after the introduction of changes to the Brazilian constitution that led to the opening of the petroleum sector to private investments, the country's energy industry evolution is in full swing: A new regulatory agency has been created, several major and independent oil and gas companies are active in Brazil, and the midstream and downstream sectors are undergoing changes that can be considered a complete restructuring.

Changes, however, do not happen in a linear pattern. As could be expected, there are movements forward and retractions, glitches and uncertainties in regulations, and a period of adaptation for all companies that had been operating in the country prior to these changes. This article will describe these changes and attempt to evaluate where the changes were successfully introduced, where the stumbling blocks are, and ultimately, where any retractions might take place. In sum, where is the petroleum sector in Brazil now relative to where it was 5 years ago?

Market potential

Brazil's economic indicators (Table 1) characterize a country with enormous energy market potential.

Moreover, its mostly urban population has a voracious appetite for energy. At the end of 1995, when the government started to open the country to private exploration investments, oil and gas production had reached a peak of 850,000 boe/d, with an average of 716,000 boe/d. Brazilian oil consumption was 1.45 million b/d in the same year.

Presently, consumption is on the order of 1.8 million b/d, while production averages 1.3 million boe/d.

Estimates for the next decade's consumption indicated a rate of increase of 4.5%/year, with consumption reaching 2.5 million b/d in 2005. Clearly, this is a market that cannot be ignored.

Demonopolization

Following the general trend towards a more liberal economic policy, on November 1995, the Brazilian Congress passed a constitutional amendment modifying sub-items to Article 177 of the Brazilian federal constitution. This modification created a new legal framework regarding the administration of the state's petroleum monopoly in the country. Until that time, the Brazilian constitution of 1988 and Law 2.004 of 1953 had given Petrobras the exclusive rights to all of the upstream and most of the downstream activities in the country. This constitutional amendment (No. 9) maintained the state's monopoly on these activities but instead of giving the administration to Petrobras, it created a new regulatory agency. This agency would be in charge of transferring these rights to private agents and Petrobras either through concessions or authorization, depending on the specific activities. This constitutional change marks the beginning of what can be called the fourth phase of the petroleum industry in Brazil.

The new regulatory agency, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), will from now on oversee the dismantling of the government petroleum monopoly by cutting subsidies, extending new concessions and authorizations to the private sector (including foreigners), and establishing the new regulatory framework for the country. Among the activities of the ANP to date, two exploration and production licensing rounds have been conducted, regulation giving open access to pipelines in the country has been enacted, and several authorizations for transportation, import, and storage of hydrocarbons have been issued to private investors.

E&P activity

One of the most important features of the new regime-and the one that merits investors' close scrutiny in coming years-is the assignment of the country's oil fields. Technically, these fields have always been the possession of the Federal Republic. In practice, Petrobras exercised these rights.

Since the enactment of the new Petroleum Law in 1997, E&P rights in Brazil are to be granted through concession contracts, preceded by public tenders organized from time to time by ANP (Fig. 1).

Petrobras was granted rights to all its fields that were under production as of August 1998. In addition, in areas where Petrobras had commercial discoveries or significant investments in exploration, it was granted a 3-year period to continue E&P activities and pursue commercial production. It is expected that many blocks currently held by Petrobras will be at the agency's disposal by August 2001, as a result of this provision.

All properties that were not under production then-or that Petrobras had declared not worth a continuing E&P effort, or that the company did not prove that it had the necessary investment in place to develop the project-automatically reverted back to the government. Nowadays, any company that complies with the technical, economic, and legal requirements established by ANP may qualify to get concessions to explore for and produce petroleum. These concessionaires are entitled to all of the oil and gas produced, subject to applicable taxes and other government takes.

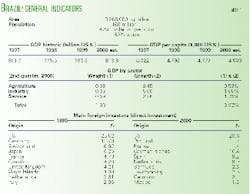

The government oil and gas take in Brazil includes a signature bonus (the minimum amount is established in a public notice tender); royalties of 10% over gross production (occasionally reduced to a minimum of 5% in cases of higher geological risks); a "special participation" with variable percentage, if any, applied to the net revenue of the fields with large production or large productivity; and an annual rental fee assessed per square kilometer. Moreover, an extra royalty of 0.5-1.0% of production applies to onshore producers and is paid directly to the appropriate landowner. Then, the regular fiscal regime affecting all companies operating in Brazil is applied. Fig. 2 shows the schematic representation of Brazil's government take in E&P activities.

E&P rounds results

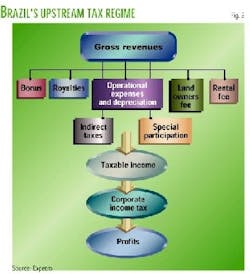

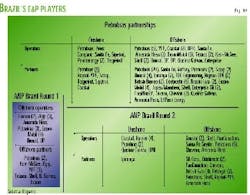

So far, two international bid rounds for E&P blocks were held by ANP. The results are summarized in Fig. 3.

Brazil's Round 1 took place in June 1999. The government collected roughly $300 million in bonuses during that round. Given the market conditions prevailing at that time, this round was considered fairly successful.

Round Two, on the other hand, has left oil executives and government officials much more pleased. ANP's director general, David Zylbersztajn, said the government was "frankly surprised and pleased by interest in the auction." Brazilian companies boosted their participation to 40% from 26% a year before. Petrobras's bids, including its participating interest in various consortia, amounted to 165.1 million real ($1 = 1.8 real), an amount equivalent to 35.26% of the total. The other top-ranked companies in bonus payments were Royal Dutch/Shell, with 85.7 million real (18.31%); Chevron Corp., with 69.5 million real (14.83%); and BG PLC, with $64.2 million real (13.71%). Brazilian private companies combined (Construtora Norberto Odebrecht SA, Rainier Engineering Ltd. Maritima, Queiroz Galvao, and Grupo Ipiranga) accounted for only 1.6% of the total bonus payments.

Brazil's government is already preparing a new E&P concession round, Round 3. According to David Zylbersztajn, this coming round will concentrate on offering acreage in onshore and in shallow offshore areas. The exact timing and acreage for this round will be announced later this year.

The general upstream indicators for Brazil are shown in Fig. 4.

Petrobras

The so-called "flexibilization" of the Brazilian petroleum sector caused a great deal of concern in the Brazilian society-so much so that, in 1996, Pres. Fernando Henrique Cardoso went before the Senate and gave his commitment that Petrobras would remain in state hands.

Accordingly, the company has not been privatized. However, it has no special rights and must compete on an equal footing with all other players in the market. One of the consequences of this "new competition status" is that it had to transfer to the ANP all nonproprietary data on the petroleum sector in Brazil (including geological and geophysical data). Almost all of this data is now in ANP's hands and is available to interested parties, through the newly created ANP Data Bank.

Although there were fears that Petrobras would have a difficult time operating in a competitive world, the latest company results point to a successful integration into this new environment.

Petrobras is one of the world's largest petroleum companies, with total domestic and international oil and gas reserves of 17.8 billion boe. Its daily average oil and gas production in 1999 was 1.4 million boe/d, most of which was produced offshore (969,000 boe/d). Petrobras operates 8,499 producing wells, 15,330 km of pipelines, 53 terminals, and 13 refineries with a nominal installed processing capacity of 1,953,000 b/d.

As for financials, Petrobras consolidated results for the 1999 reporting period included gross operating revenues of $22.546 billion, net operating revenues of $16.320 billion, and a net profit of $982 million.

Numbers, however, fail to expose the dynamic transformation the company is going through. The Cardoso government has replaced and changed the legal composition of the board to help steer the company in this new era. Note that the government has maintained its control over the direction of Petrobras by keeping the chairmanship of the company's board of directors in its hands-the chairman is the Minister of Mines and Energy. However, although the government, as promised, is maintaining the control of the company, it is letting go of all of the shares it has above this controlling requirement (50% plus one voting share).

Accordingly, the government recently put up for sale 28.48% of Petrobras's voting stock on the market. This corresponds to 16.63% of the company's total stock. A part of the Petrobras shares not under government control were offered in Brazil. Brazilian workers could opt for exchanging up to 50% of their Employees Indemnity Guarantee Fund (FGTS) for Petrobras stock. The operation attracted less that 10% of the FGTS funds allowed to be exchanged. Petrobras gained 150,000 new shareholders, and the operation resulted in the exchange of 1 billion real, which still was considered "a success, given the fact that it is a first experience," by the National Development Bank (BNDES).

As opposed to the relatively mild repercussions from this sale to Brazilian workers, the international launch of American Depositary Receipts last August was a great success and resulted in raising $2.5 billion for the government. Adding the FGTS-exchanged stock (Brazilian process) with the ADR sales (New York Stock Exchange process), the overall result was $4 billion raised in the sale of 28% of Petrobras voting capital.

In 1999, in order to guide the company through this radical change the government appointed a new president, Henri Philippe Reichstul. Although Reichstul had no previous experience in the oil industry, he had plenty in both the government and financial worlds. Within the Brazilian oil industry, he is proving to be a fast learner. He has combined his financial experience and his new knowledge of the industry to design a new strategic plan for Petrobras. Included in this plan is the integration of Braspetro-the company's international arm-into the main company as a division headed by a director. This is a significant move, as it has changed the way Petrobras deals with partners. Nowadays, a new joint-venture partnership model is evolving: one that includes the swapping of participation in international E&P projects for participation interest in major development and production projects in Brazil.

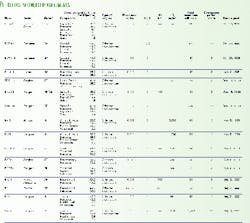

Finally, since 1998, Petrobras has been signing joint-venture agreements with several domestic and international players, sometimes as operator and other times as a simple participant. Table 2 details Petrobras's recent partnership agreements.

Midstream, downstream restructuring

The new regulatory framework also brought significant changes to the ownership and use of hydrocarbon processing, transportation, and storage facilities in Brazil. Under the new law, ANP will now be in charge of issuing special authorizations to any company or consortium established under Brazilian laws that wishes to build and operate refineries, gas plants, terminals, or pipelines.

Any interested party may now share common access to existing and future pipelines and marine terminals, by paying adequate remuneration to the owner of these facilities; ANP will regulate priority rights (a first case has been under arbitration between Enron Corp. and Brazil's TBG) and will establish tariffs in case the parties fail to reach an agreement. Imports and exports of oil, natural gas, and petroleum products will need an authorization issued by the ANP on a case-by-case basis. Finally, current regulations allow E&P investors to sell their production in Brazil and receive payment based on international market prices.

Refineries

As mentioned, since 1953, Petrobras had been responsible for supplying the domestic market with petroleum products, fuel alcohol, and natural gas and, until recently, had a monopoly on imports and exports of crude oil and petroleum products.

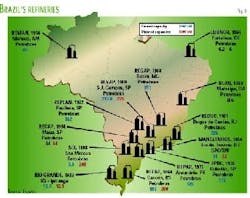

However, it did not have complete control of the country's refining capacity. The private companies Ipiranga and Manguinhos own two small refineries that were built prior to the founding of Petrobras. However, a de facto monopoly still prevails in the country. That is because Petrobras has the remaining 10 refineries, plus an asphalt plant, and accounts for 98.5% of Brazil's total capacity and daily output.

Fig. 5 illustrates the locations and the capacities, both current and projected for the year 2001, of Brazil's 12 refineries. The estimated capacities for 2001 are based on upgrade programs currently scheduled, as reported by Petrobras and the other operators.

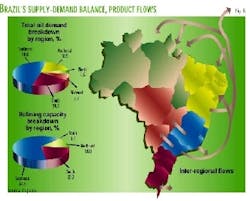

While representing a key element in the state company's activities, refining operations also constitute one of its biggest challenges as it enters a new era of competition and world market prices. Today's installed refining capacity is able to supply an estimated 80% of the domestic market's petroleum product needs. In terms of crude supply, about 70% already comes from Brazilian fields.

It is expected that the government will encourage Petrobras to forge partnerships with private investors in its existing refineries, aiming at diminishing its hegemony in this sector. A pioneering precedent was set recently by Repsol-YPF SA, which acquired an interest in Petrobras's Refap refinery, near Porto Alegre, in exchange for service station assets in Argentina and an interest participation in a refinery there. In its turn, Petrobras has also recently expanded its refinery capacity to Bolivia, through the acquisition of Guillermo Bell and Gualberto Villarroel refineries (20,000 b/d and 40,000 b/d capacities, respectively).

Storage, transportation

As a consequence of its former capacity as the operator of the monopoly in the petroleum sector, Petrobras now owns most of the storage tanks, marine terminals, crude and product pipelines, and ships and barges utilized to move oil, gas, and petroleum products throughout Brazil's onshore and offshore territory.

This impressive collection of assets consists of 64 owned ships and 50 leased vessels, with an overall capacity of 7 million dwt; a system of oil, gas, and product pipelines spanning 15,330 km; and 53 crude or products storage terminals with 66.723 million bbl of total capacity.

Only 22% of all petroleum products is transported by pipeline, while 18% is moved by train, and 15% by truck. The balance (in 1999, about 70.6 million tonnes) is shipped along the coast, either on coastal freighters or barges.

Fig. 6 illustrates the unbalanced situation between the existing refining infrastructure, mainly concentrated in the Southeast (64.6%), and the new regional demand profile. Today, more than half of Brazils' petroleum products consumption is situated in other regions, with increases in the Northeast, North, and West-Central regions. Current interregional flows normally are directed to the supply of these newly growing regions by national or foreign products.

On May 1, 2000, Petrobras's newly formed subsidiary, Transpetro, took over all transportation of crude oil, natural gas, and derivatives-including pipelines and storage terminals. Transpetro was created as a result of a provision of the new Petroleum Law and is intended to be Petrobras's logistics arm. It will also be subject to the open-access rules and thus will have to allow shared use by third parties under nondiscriminatory tariffs.

Natural gas

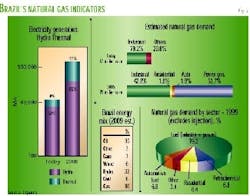

In the Brazilian energy mix for 1998, natural gas accounted only for 3% of the total. However, government projections estimate that its share will increase to 10% by 2005. This increase is projected as a result of the federal government's Electric Generation Priority Program that has targeted the construction of 49 thermoelectric power plants spread throughout the country. Forty-three projects out of the total have natural gas as their fuel source.

Ten percent of the energy mix is not a significant participation compared with other countries, even in South America. For instance, natural gas accounts for over 60% of Argentine energy consumption. However, when looking at a huge market such as Brazil, one must consider the absolute values any of these percentages may refer to. According to government data, Brazil's natural gas consumption in 1998 was 150,000 boe/d and, if the projected increase is achieved, it will reach 580,000 boe/d in 2005.

Interestingly, although the government justifies the increase in natural gas consumption as a direct result of the increase in the use of natural gas to generate electricity, according to the projections made by Petrobras for natural gas demand up to 200,8 generation of electricity will only account for half of the national demand projected. The industrial sector will be responsible for most of the rest (Fig. 7).

In 1999, an average of 33.4 million cu m/day of natural gas was traded, consumed, liquefied, flared, or reinjected in the country. Note that, of the total 10.8 million cu m/day that is listed as reinjected, 4 million cu m, in fact, is flared, according to Petrobras sources.

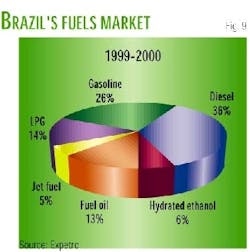

Fuels market

In terms of volumes traded and market growth projections, the Brazilian distribution market for fuels easily qualifies as the most attractive in Latin America, moving no less than 75 million cu m in 1999, and growing at a consistent rate of 5-7%/year.

Brazil's service station network is by far the largest in South America. According to the latest assessment by ANP, in June 2000, there are currently 28,929 retail outlets registered and operating in Brazil. Density per square kilometer is low due to the size of the country, but these outlets are relatively well distributed throughout the country, with higher concentration in Brazil,s most populated states. The market distribution by region, by brand and by product, is shown in Figs. 8-9.

The two main concerns regarding the Brazilian fuels market that remain are pricing policy and the enforcement of quality controls. Historically, prices were used as a tool for implementing a number of macroeconomic and political measures. This "market interference" from the government is still happening. Recent concerns regarding the return of higher inflation rates forced the government to take a step back in the process of gradually allowing market forces to determine prices at the pump. The process of eliminating cross-subsidies, allowing importation of fuels, and leaving the distribution companies and retailers free to set their own profit margins was abruptly interrupted by the government's recent decision to re-establish strict profit margin controls. These new measures will have a great impact in the market, because more than 300 new fuel distributors have appeared after the oil demonopolization began.

However, retail profit margins are not the only factor influencing prices at the pump. Prices are distorted by a complicated tax structure that was inherited from monopoly times. This structure includes special compensation collected by Petrobras at the refinery gate to make up for differences between the cost of crude produced in Brazil and the international prices applied to the imported crude. Basically, this old system has not been adapted to the new realities for two reasons: 1) Because this requires a federal law to be voted on by Congress; and 2) Pro bably most importantly because the government has started to enjoy the extra revenue provided by the collection of this unofficial "special tax"-to the point that it has included this annual income as one of the target accounts items for the International Monetary Fund.

Despite the fact that price liberalization is the keystone for the effective implementation of the new Petroleum Law, it seems that the Ministry of Mines and Energy and the Ministry of Finance will still be in charge of controlling internal prices until the drafting of specific (fiscal and regulatory) directives to achieve this general aim are finalized, it is hoped, by 2001.

Conclusions

As this article has shown, the petroleum sector in Brazil has changed drastically in the last 5 years.

The country has moved from a monopolist E&P environment with only Petrobras operating in the country to a segment where, today, 36 international and domestic companies are active in a myriad of projects (Fig. 10). ANP has been extremely successful in establishing a clear, transparent, and competitive concession process for the country. The results of the two bidding rounds are a clear proof of that.

Brazil also has moved from a monopolist midstream and downstream sector to one where access is open for competition. In this case, and by virtue of the large sunk investments necessary to make the segment operational, one can not claim a complete success of the competitive model. Although regulations do determine open access, in practice, there will be lots of glitches. Moreover, ANP's arbitration process is still in its infancy, and it will have to be improved in all aspects. The same can be said regarding the refining sector. It is easy to establish new regulations permitting the building of new refining capacity. However, dealing with a refiner who holds almost 98% of the total refining capacity in the country by using a competitive regulatory model will not be so easy.

The retail sector is the one presenting the most surprising results. That is because it was the only one where, in theory, competition was always present. However, as was explained, pricing in the sector is still being used as an "inflation control" tool by the government. Consequently, dismantling these controls is proving to be a very sensitive issue. Perhaps this is the sector where there will be the most amount of retraction in policy, as the government fights to keep its popularity ratings. Curiously enough, it is exactly where new players have proliferated and where market growth perspectives are steadily enthusiastic.

Finally, overall, one can say that the opening process of the petroleum industry in Brazil has been rather successful. Although the government might still face some difficulties in certain areas or sectors, the general guidelines and specific rules are set. Now, the game can begin.

The authors

Jean-Paul Prates is a founding partner of Prates & Carneiro-Advogados and Expetro. Both firms specialize in assistance to oil and gas industry players in Brazil. He has a law degree from the University of Rio de Janeiro; a masters in economics and management from Institut Fran

Annette Hester is a partner in Expetro and general manager of the firm's Canadian office. She has a BA and a masters in economics from the University of Calgary. She assists clients in North America and Latin America on projects related to petroleum, gas, and energy markets and helps Canadian government agencies and companies maintain business relations with Latin America, especially Brazil. Hester participated at several round table discussions of the government of Canada on hemispheric integration and trade negotiations and served as a witness to the Canadian Parliament on Free Trade in the Americas (FTAA) agreement. She is also a director of Cabra Enterprises, a Canadian company specialized in the geologic consulting for Canadian and Latin American clients.

Alexandre Frickmann is the general manager of Expetro's databank (datapetro.com.br), which will be available to the public by Oct. 16, 2000. He has an economics degree from University Cândido Mendes, Rio de Janeiro. Frickmann has specialized in the creation and development of databases related to the Brazilian fuel and energy markets, including the creation and updating of digital mapping of economic information with GIS.