Petroleum industry faces challenge of change in confronting global warming

Change presents challenge, to us as individuals and as groups of people in organizations and institutions. The petroleum industry faces such a challenge of change. The issue of climate change, specifically potentially threatening "global warming," confronts the petroleum industry with the need to respond positively to public concern.

Among the most extreme of the industry's critics are those who see climate change as the means to end the oil and gas industry. That would be change, indeed.

In mid-December 1997, in Japan, the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) was agreed to by over 160 nations. The Protocol has been hailed by some observers as an "important initial step" in addressing the challenge of climate change. Others have dismissed it as a "seriously flawed treaty."

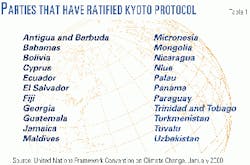

A senior US Government official referred to it as "a work in progress," and the European Parliament described it as a "draft for future negotiations." In the 15 months following Kyoto, the Protocol was signed by virtually all of the nations attending the meetings in Japan. Over 20 governments have actually ratified the treaty (Table 1), although none of any consequence in terms of impact on the central feature of the Protocol, the commitment by developed countries to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG), significant among them, carbon dioxide and methane.

A treaty to reduce emissions of CO2 should be enough of a challenge to the petroleum industry to command serious attention. But Kyoto is just the beginning.

Since the conference in Kyoto, the Parties to the Protocol continue to negotiate "principles, modalities, rules, and guidelines" for implementing the Protocol. The countries have as their objective reaching agreement on rules and regulations at a Conference of the Parties (COP-6) to the FCCC in the Netherlands in November 2000, just after the US presidential election.

What is the Kyoto Protocol all about? What is being negotiated now, leading up to COP-6? What are the prospects for ratification of the Protocol? What are the concerns of the petroleum industry? And what courses of action should oil and gas companies be exploring? What sort of risk management strategy should a company pursue? In short, how much change should the industry contemplate?

Science sufficient for political action

Climate change, or global warming, engenders not only concern but also passion. Some would have us believe we face-and soon-the ultimate apocalypse. Then there are those who would argue that the issue of climate change is a construct of social engineers.

Still others, perhaps somewhat arrogantly, are intrigued with the opportunity of attempting to manage the climate.

The science of climate change is complex but relatively straightforward. The "greenhouse effect" is real. Without it, planet Earth would quite probably be uninhabitable. Climate changes over time, sometimes quite dramatically, as geological evidence amply demonstrates.

The current concern over "global warming" is driven by the coincidence of a rise in global mean temperature and an increase in the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, both taking place over the past 150 years, essentially the period since the dawn of the industrial revolution.

The theory propounds that human activity (anthropogenic forcing), particularly the release of CO2 in the process of burning coal, oil, and natural gas, is responsible for the increase in GHG concentrations. This anthropogenic forcing, in turn, has resulted in the increase in the earth's temperature.

Left unchecked, continued and growing GHG emissions could result in dramatic and perhaps undesirable changes in the global climate over forthcoming centuries.

It is not considered "politically correct" to challenge the science of climate change. If one listens to politicians and the media, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its 1995 Second Assessment Report (SAR), "reached consensus" that "global warming" was happening and that humans were responsible.

The IPCC did so, however, in a very cautious fashion. The much quoted "ellipsethe balance of the evidenceellipsesuggests a discernible human influence on global climate" is hardly a strong statement. Moreover, it is further qualified later in the SAR: "Although the global mean results suggestellipsethey cannot be considered as compelling evidence of a clear cause and effect link between anthropogenic forcing and changes in the earth's surface temperature." A Third Assessment Report (TAR) will be released in 2001.

How much further has the assessment of climate change evolved? Robert Watson, Chairman of the IPCC, in testimony before a US Senate committee on May 17, stated that, since 1995, there have not been any new major breakthroughs in the science. Watson then advised that the TAR would put forth a "consolidation" of evidence of climate change and human influence. We can anticipate, therefore, an advancement of the political science of climate change in the TAR next year.

A final comment on the science. The FCCC, adopted at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, has as its ultimate objective "ellipsethe stabilization of greenhouse concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."

Largely ignored by politicians and the media is the fact that the "level" is not known. The European Union has concluded, with no apparent scientific underpinning, that the level is about twice the level of concentrations at the beginning of the industrial period. Some additional perspectives on this subject can be anticipated in the forthcoming Third Assessment Report of the IPCC.

The science is what the science is. The politics of climate change move on, driven in part by the philosophy commonly referred to as the "precautionary principle," the view that scientific proof is not required to justify action and response.

Kyoto Protocol to The Hague implementing provisions

The Kyoto Protocol is not really an environmental treaty. It is a political document that, if it is ratified and comes into force, will have significant and far-reaching economic and societal implications. We may have to question how we are organized as societies, how we govern ourselves, what direction our economies develop, and what individual freedoms we may enjoy. Obviously, what energy sources we may use will also be in the balance.

The Kyoto Protocol in many ways is an incomplete document, but in one respect, it is very specific. The Protocol requires developed countries (industrialized nations referred to in the Protocol as Annex I Parties) to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases during the first "commitment period," 2008-12, by an average of 5.2% below the levels of 1990.

There are individual targets for the 34 Annex I Parties. The nations of the European Union are treated as a group for purposes of the Protocol, although they have, since Kyoto, allocated their 8% reduction commitment under the Protocol among the 15 member states.

The US has undertaken a 7% commitment and Japan 6%. The developing countries (the so-called Group of 77 plus China, actually made up of over 130 nations) have no obligations under the Protocol to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.

The Kyoto Protocol was the result of a forced march triggered by the Berlin Mandate (April 1995) adopted at the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP-1). The Kyoto Protocol left virtually all implementation decisions for future negotiations.

That process was taken up in Buenos Aires (COP-4) resulting in a Plan of Action, another forced march, "with a view to" adopting implementing decisions by COP-6 to be held in The Hague in November 2000. (Dare we refer to such an agreement as HIP, The Hague Implementing Provisions?)

The march plods on. Negotiating sessions took place in June, and more are scheduled for September. A proliferation of workshops, "informal consultations," and bilateral and multilateral planning meetings supplement the formal negotiating sessions.

None of the major deficiencies of the Protocol have been resolved. Critically important subjects, such as compliance, generation of emissions credits through investments and trading, carbon sinks, financial and technology transfers to developing countries, and compensation to countries severely affected by climate change and by policies undertaken by other countries to mitigate emissions, remain on the negotiating table.

Completing them to the satisfaction of over 160 negotiating partners will not be an easy task. On one issue alone, mechanisms for generating or acquiring emissions credits (through investments or emissions trading), the negotiating text following the June 2000 session was over 125 pages, with more submissions by Parties anticipated.

By contrast, the entire Kyoto Protocol is only 35 pages.

A number of negotiating blocs are engaged in the current debate. The European Union (Table 2) is perhaps the most aggressive proponent of early and dramatic action and, ironically, of constraints on implementing policies.

The JUSCANZ core countries (Table 3), which include the US and Japan-since Kyoto referred to as the Umbrella Group-provide a counterweight to the EU aggressive/constraint posture. The remaining developed countries include Russia, Ukraine, and the Eastern and Central European nations (referred to as "countries in transition" or "emerging market economies"), as well as a few others (Table 4).

The over 130 developing countries tend to negotiate as a bloc, even though there are various sub-blocs, regional groupings, and sector-specific alliances, for instance, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the Organization of Small Island States, Latin America, Africa, etc.

Michael Zammit Cutajar, Executive Secretary of the UN FCCC and thereby head of the not-inconsiderable staff supporting the Protocol negotiations, has advised Parties to the Protocol that The Hague COP-6 will be "judged successful if its resultsellipsetrigger ratification of the Kyoto Protocolellipsesufficient for its entry into force [and] motivate significant action by non-Annex I Parties [developing countries] to enhance their contributions to the achievement of the Convention's objectiveellipse."

The European Union has called for the ratification of the Protocol by 2002, the 10th anniversary of the Rio Earth Summit. Ratification by the developed countries (Annex I) would seem to be dependent on how the outstanding issues of the Protocol are resolved, if at all, at The Hague meeting in November.

Implementing provisions will determine the feasibility and the economic and social costs of policy options that may be undertaken by developed countries.

Feasibility and costs will, in turn, determine the "political costs" of attempting through policy initiatives the daunting task of reducing emissions of greenhouse gases from trend lines that are not trivial.

In the US, the Department of Energy projects that reducing emissions to levels 7% below 1990 levels will represent at least a 30% reduction off the current trend line to 2008-12. The challenge of The Hague negotiations, therefore, is no small matter for the US delegation.

An additional dilemma presents itself as a result of flawed drafting of the Protocol. Final approval of virtually all of the unresolved issues that are critical to implementation of the Protocol must await the convening of the first session of the Conference of the Parties (to the Convention) constituted as a Meeting of the Parties (to the Protocol).

In the jargon, only understood by true aficionados of UN-speak, this event is referred to as COP/MOP-1. The meeting of COP/MOP-1 cannot happen legally until the Protocol has been ratified and has come into force.

The question raised is why any country would ratify the Protocol without knowing for certain the details of the rules and regulations for its implementation, a veritable "Catch-22."

Notwithstanding the complexities of the negotiations, in all likelihood, the Parties will arrive at a number of agreements in The Hague that will allow them to claim that COP-6 is "a success."

It will be left to individual countries and future negotiations to pick up the pieces. Industry in general, and the petroleum sector in particular, cannot afford to be idle, not in the run-up to COP-6 nor in the continuing national and international debate and negotiations on issues relating to the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol.

Critical issues for the petroleum industry

Global industry as a whole has an enormous stake in the outcome of current and future negotiations on issues surrounding climate change. Three of these are of particular concern to the petroleum industry.

The Kyoto Protocol provides for "flexibility mechanisms" in recognition of the fact that costs of reducing emissions vary significantly among national economies. The mechanisms include joint implementation (JI), the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), emissions trading (ET), and carbon sinks generated through land use change and forest management.

JI and CDM are essentially foreign direct investment with embellishments. JI involves joint projects in a developed country that would generate emissions credits to be used in honoring obligations in another developed country.

CDM projects would be similar except they would be in developing countries generating emissions credits to be used in developed countries. Emissions trading would involve the purchase and sale of excess credits from one developed country by another. Carbon sinks, in principle, could be vehicles for JI, CDM, and ET.

The mechanisms appeal to industry, because project development, environmental management, and trading are areas of considerable experience and expertise in companies. The details of how these mechanisms are to operate are as yet not agreed, and some of the positions adopted by the Parties to the Protocol are not encouraging from the standpoint of future industry participation.

To illustrate, consider the negotiating objectives of the EU as released this past June. The EU maintains that at least 50% of the emissions reductions to honor commitments in the Protocol must be achieved domestically.

This constraint, referred to as "supplementarity," would limit the use of flexibility mechanisms by countries-and presumably companies as their agents-in achieving emissions reductions. Competitive distortions could result, because not all countries have equal costs associated with emissions reductions.

The EU would also restrict CDM projects to renewable energy projects, energy efficiency investments, and demand-side management programs in the fields of transportation and energy. No nuclear projects or carbon sinks developments would be allowed. Further, forest management and land use change activities would not be eligible for emissions offset consideration until a second or later "commitment period"-in other words, beyond 2012.

Negotiations on the second commitment period should be brought forward to 2001, advancing consideration 4 years vs. the Protocol provision of 2005. Finally, with respect to the issue of compliance, the EU calls for a rigorous compliance process, with financial penalties (proposing a Compliance Fund) in the event of noncompliance. The Umbrella Group generally opposes these proposals.

The developing countries argue that institutional and financial features of CDM projects should apply as well to JI and ET. These could add significantly to the transaction costs of JI and ET, costs that will determine the willingness of industry to participate in using the mechanisms as a means of reducing emissions.

Industry acknowledges that there is a need to be able to demonstrate that emissions reductions are real and measurable. Once requirements move beyond "certification," however, costs become major factors in the profitability of such projects.

The prospect of a CDM Reference Manual has also been put forward, suggesting that CDM activity would be managed by the Climate Change Secretariat in Bonn.

The second concern, compliance and penalties for noncompliance, is primarily a matter for national governments to address, because they are the Parties to the Protocol. Nevertheless, compliance issues concern industry.

International obligations with respect to compliance will undoubtedly play themselves out in national legislation, in terms of reporting, verification, and other areas. Compliance also may have implications for a company's ability to use the flexibility mechanisms to comply with emissions reduction obligations.

The EU, supported by an number of other countries, argues that a Party (i.e., a country) should not be allowed to engage in JI, CDM, or ET if it is found to be in noncompliance. It is not clear what impact such a proposal would have on the ability of a company in a "noncomplying" country to engage in the mechanisms.

Further, what is the liability of a company that has acquired in good faith emissions credits, through projects or trading, to be used to comply with obligations in a home country if the country from which the credits were acquired is later found to be in noncompliance?

These are not trivial issues. Industry must engage in this debate, both nationally and internationally.

The third concern for the petroleum industry is a national one, the "downloading" of emissions reduction obligations to industrial sectors and ultimately to individual firms. The Kyoto Protocol commitment is a treaty commitment by governments that, if and when ratified, becomes a national obligation to reduce emissions.

Some vehicle, presumably, would have to be found to move that obligation to firms and individuals that in the final analysis are responsible for generating emissions.

The petroleum industry could be held doubly accountable: first, for emissions resulting from its own operations, and second, for emissions by customers using the industry's products of oil and natural gas. Control of its own operations is a legitimate responsibility, and emissions can be reduced by energy-efficient investments and offset by acquisition of emissions credits.

But what is the vehicle by which the industry may be requested to "reduce" emissions of its customers? Consider such options as allocation, rationing, taxes, and exhortation. Are not these important concerns for the petroleum sector?

Kyoto Protocol prospects and beyond

The Kyoto Protocol is a challenging document. In all likelihood, however, the forthcoming meetings at The Hague (COP-6) will not bring to closure the debate and disagreements among Parties so that ratification of the Protocol could proceed in an timely fashion.

Eileen Clausen, President of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change and a lead negotiator for the US government in Kyoto, at a conference in London on June 20, admitted to the "sheer impracticality of meeting the targets according to the Kyoto schedule, together with the potential costs involvedellipse[and] no targets for the developing world."

Ironically, Clausen's concerns are precisely those raised in August 1997, prior to Kyoto. In a unanimous resolution, the US Senate advised the Clinton administration, of which Clausen was then a part, against signing a treaty that would damage the US economy and that did not provide for emissions reduction commitments by developing countries.

Paul Portney, president of Resources for the Future, Washington, DC, in a humorous but profound comment more than 18 months ago (March 1999) at a conference sponsored by the US Department of Energy, suggested that the Kyoto Protocol did not have a "snowball's chance in hell of coming into effect [see box]."

Only a few countries can even hope to achieve their targets in the minds of most observers.

The UK may reach its target, if it continues its "move" toward natural gas and shuts down its coal industry. Germany could perhaps reach its 2008-12 target, if the eastern German provinces do not recover economically, but the country faces an enormous challenge for the future with the government's announcement that it will close all nuclear power facilities throughout the country over the next 20 years.

Other European countries face a variety of concerns: relying on taxes, already very high on energy fuels; and on voluntary agreements by companies to reduce emissions with a promise to exempt participants from future carbon taxes.

EU cohesion is questionable in any event, if one considers the wide range of national emissions reduction commitments that comprise the 8% target agreed at Kyoto. Germany has agreed to a 20% reduction, the UK to 12.5%.

At the other end of the spectrum is Greece with a 25% emissions increase allowed and Portugal with a 27% increase. How equitable will this "common but differentiated" burden be perceived in the EU, particularly in the northern countries? Japan can not make its target without additional nuclear power plants, a prospect certainly called into question by the recent accident at a reprocessing facility.

New Zealand reports that methane emissions from sheep are already over l990 levels by 45%, while CO2 emissions are up 19% and nitrogen oxide emissions by 24%.

The US, with the aforementioned challenge of over 30% vs. the trend line, seems unlikely to achieve its target without substantial emissions trading, conjuring up the unwelcome image of a potentially massive wealth transfer to Russia or some other surplus states.

The conclusion to be drawn can only be that, at some point during the early years of the next US presidential administration (regardless of political party), the Kyoto Protocol will be declared unworkable.

This announcement, however, will not end climate change concern. The Protocol simply stands in the way of a more rational and long-term approach to addressing the challenge of climate change, an approach in which the petroleum industry can play a leading role.

Challenge of change

The science of climate change remains uncertain. Moreover, the costs of emissions reduction and the potential impact on the growth of the global economy remain subjects of wide-ranging debate.

The politics of climate change, however, remains its driving force. Industry, therefore, and particularly the energy sector, must step up and be seen and be heard. For industry to be effective, it should view the challenge as one of risk management, embracing change in a cost-effective and timely fashion, avoiding costly overreaction, but ready to seize opportunities.

The petroleum industry must be seen as part of the solution to the challenge of global warming, not, as some would have us believe, as the problem. The industry must obviously participate in the public policymaking process, both nationally and internationally.

The industry clearly has a right and an obligation to participate-a right because of the importance of the petroleum industry in the global economy, an obligation because customers, employees, communities, and other stakeholders, including governments, have an interest in the industry's participation.

Whether individual companies act on their own or in alliances with other petroleum companies or with industry associations, it is important to engage and remain engaged in the process. And that engagement must be, and must be seen to be, a positive contribution to public policymaking.

The petroleum industry must also change its long-term strategy. The primary business of the petroleum industry is and will remain the development and delivery of resources to supply what one oil company senior executive referred to as "the unprecedented global hunger for energy." However, that task must be accomplished with an expanding concern for the environmental and societal concerns of the many different nations and peoples around the world.

It will not be sufficient to address climate change solely within the confines of one's own company operations. It will be necessary, of course, to closely monitor and control operating activities to insure that GHG emissions are managed in an environmentally and energy-efficient manner. But more will be required of the industry.

The petroleum industry also must be alert to the possibility that, during the current century, the evidence, direction, pace, and consequences of global warming will become so compelling that dramatic measures must be taken to avoid potential environmental disaster.

The petroleum industry, therefore, needs to take a long-term perspective with respect to research and development of alternative fuels and technological opportunities, such as sequestration, that could provide viable and economic options if it is necessary to move to a carbon-free energy mix. Adaptation must also be seriously considered; it is not simply a default option.

Support for continued scientific research in the field of climate change remains important. Investments in developing countries, particularly in electric power generation, can help these countries incorporate environmental and technological standards and practices that will provide not only economic growth benefits but also societal enhancements in the quality of life.

The challenge of change for the petroleum industry confronting climate change is that of reasserting and enhancing its role of leadership in promoting and supporting growth in a rapidly expanding global economy.

No other industry is better qualified and has more experience in this activity. No industry has more experience in the management of risk, whether it be political, economic, financial, technical, environmental, or social risk.

What is needed by the petroleum industry is courage to accept the challenge and a willingness to change.

The author-

Clement B. Malin retired in December 1998 as vice-president, international relations, of Texaco Inc. During 1994-98, he served as head of delegation for the International Chamber of Commerce to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.