Caspian area refineries struggle to overcome Soviet legacy

Refineries in the Caspian area are struggling to overcome their legacy of outdated technology from the Soviet era.

Although the countries have enormous potential to become a refining center, expensive and inadequate crude supplies, poor product qualities, and improper payments contribute to their troubles today.

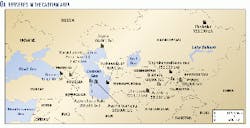

Prior to the break-up of the former Soviet Union (FSU) in 1991, a common feature of the 10 functioning oil refineries in Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan was their integration into a broader regional network. They were designed to function as part of a monolithic, centrally controlled Soviet oil industry. Breaking up this unified industry has proven much more difficult than breaking up the political union.

These countries have been unable to truly gain political independence from Russia, because they cannot create independent energy systems and markets.

Today there are 12 refineries in these five countries. Georgia and Uzbekistan each have a refinery that was built after 1991.

Industry problems

The 10 plants built before 1991 remain in various states of disrepair. Prior to 1991, they did not have access to the latest western technologies. They were constructed with Soviet design and manufacturing processes.

According to the World Bank, in 1991, their secondary oil processing capacities (in percentage of primary crude distillation) were as follows: Azerbaijan, 16.3%; Georgia, 13.1%; Kazakhstan, 30.6%; Turkmenistan, 15.6%; and Uzbekistan, 48.5%.

Thus, the refineries were essentially hydroskimmers with minimal capacity to convert heavy fuels into light products. The output mix of the refineries was largely composed of heavy products such as residual fuel oil.

In 1991, the refineries were largely dependent on Russian crude oil. The percentage of Russian crude oil in refinery throughput in the republics of the Caspian region was as follows: Azerbaijan, 25%; Georgia, 86%; Turkmenistan, 4%; and Uzbekistan, 85%. Even Kazakhstan, the second biggest oil producer after Russia, relied on Russian crude for 74% of its crude input.

Today, the refineries are running well under their nameplate capacity, because they continue to depend on Russian oil, which is steadily less available.

Currently, the refining sector in the Caspian region has several problems:

- The share of heavy fuel oil in refinery output is, on average, 35-40%. This figure is 20-25% in Western Europe and 10% in the US.

- Refineries have limited capacities for converting bottom-of-the-barrel fractions of oil into light products. They largely rely on catalytic reforming and hydrotreating processes rather than catalytic cracking, hydrocracking, and thermal operations.

Catalytic cracking, hydrocracking, and thermal operations represent only 12% of crude charge capacity, compared with 32% in the UK and 30% in Germany.

Coking has made some impact in the region and could play a larger role in the future. Coke product is potential feed for new power-generation facilities or existing coal-based power plants.

- Gasoline quality is well below European standards. Caspian area refineries mainly make low-octane, leaded gasoline. This is not a big problem, because most vehicles in the FSU are designed for this type of fuel.

Poor-quality gasoline will be a problem, however, when more cars are imported and emission standards become more stringent.

- The refineries' petroleum products are high in sulfur and unprofitable in export markets. Heavy fuel oil, because of its high sulfur content, cannot be used for power stations in Europe (unless fitted with flue-gas desulfurization) and can be sold only as a cheap feedstock for further processing. High-sulfur diesel also limits diesel's use to cheap feedstock.

- The narrow slate of refined products in combination with a fixed crude slate means that refiners cannot react to seasonal changes in consumption patterns. That is, they cannot adjust to the need for more light products during the summer and greater quantities of diesel during the winter.

- Compared with similar types of plants in Europe, energy consumption and losses in the Caspian area are high.

- There is a lack of investment in refining, because governments are unable to finance major revamps, and foreign investors are reluctant to invest in downstream businesses. It is more attractive to export crude than to sell products into the domestic market, where customers often are unable to pay.

Industry outlook

Refineries in Central Asia are geographically remote from world markets for crude oil and product. Although the outlook for exporting crude oil and natural gas is good, as has been demonstrated by Chevron Corp. (Tengiz) and the Caspian Pipeline Consortium pipeline investment, moving refined product is much more difficult.

This difficulty offers the Central Asian refining industry a high level of natural-price protection, because competing supplies outside the region must travel over long distances to reach markets.

As in the past, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are primarily producers today. Azerbaijan is a producer and a transit country. Georgia's main role is as a transit country. Uzbekistan is the only country that is self-sufficient in crude supplies and refined products for its domestic market.

As a result of political and geographic reasons, as well as the absence of hydrocarbon resources, countries like Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan will not take part in the regional competition of oil development.

Given their landlocked position and the inevitability of growing domestic demand for oil products, the countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus must continue to rely on their own refineries.

The justification for the initial construction of these refineries was based on the needs of the Soviet era and the requirements of the Soviet economy, rather than on the particular domestic or industrial needs of each country.

All refineries in this region are confronted by the challenges of moving into a new and independent era. They are saddled with old technologies and equipment and shortages of crude. They remain embroiled in a nonpayment crisis in which their customers fail to pay for oil products received.

Recent high oil prices on the world market affect these refineries negatively. Oil extraction and exports offer higher and quicker profitability than refining.

In addition to looking at export markets, the countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus will have to develop opportunities within their regional markets. Theoretically, the total regional market in the above-mentioned countries is more than 70 million consumers, but, in reality, this is a segmented, underdeveloped market.

Taking into account the size of Caspian oil reserves, with economic integration and cooperation, the region has the potential to become a center for refining. In addition to serving their domestic markets, these refineries could provide Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Europe with a range of petroleum products.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan has two refineries with a total capacity of 442,000 b/d. They are Azerneftyanajag (203,000 b/d) and Azerneftyag Baku (239,000 b/d), both located in the vicinity of Baku.

In the past, Azerbaijan processed oil in excess of its own needs. It shipped a significant amount of oil products within the USSR. Today, however, its two refineries are so run down that they are able to function at only 40% of capacity, processing 178,000 b/d.

Oil production in Azerbaijan reached 280,000 b/d in 1999, below the nameplate capacity of its two refineries. Domestic consumption was 125,000 b/d, down from a peak of 170,000 b/d in 1990.

Azerbaijan estimates that upgrades at the two refineries, which will permit it to process 260,000 b/d, will cost $600-$700 million.

In 1998, Japanese companies Nichimen Corp., Tokyo, and Chiyoda Corp., Yokohama, began work on the master plan for modernizing the two refineries. In May 2000, they presented their recommendations to the Azeri government.

Combining the two refineries is one option being studied. Future production would be focused on transportation fuels and specialty lubricants rather than fuel oil, because fuel oil will likely be replaced in the power sector by natural gas. Azerbaijan's master plan has set an optimistic date of 2003 for the country's gasoline specifications and usage to be brought in line with European standards.

The plan envisions the construction of an 855-km oil-products export pipeline from Baku to the Georgian Black Sea coast, by which 60,000 b/d of products will be sent to the European market by 2010.

With high oil prices in 1999, Azerbaijan was exporting its oil instead of stockpiling it for winter refining needs. It was caught short during the winter of 1999-2000, however, when the country experienced serious shortages of fuel oil in its power sector. This year, the government issued a decree on June 19, 2000, forcing the diversion of oil from lucrative export markets to domestic refineries to build up fuel oil stocks for the country's winter power needs.

Georgia

Georgia has two refineries with a total capacity of 109,000 b/d.

The country's main refinery (106,000 b/d) is located in Batumi, the capital of the autonomous republic of Adzharia. It was built in the 1930s. A second, much smaller plant is located in Sartichala (2,400 b/d), 30 km east of Tblisi. It began operations in 1998.

Georgia is attracting considerable interest from foreign investors in its refining sector because of the country's strategic location as a transit hub for crudes from the Caspian region.

CanArgo Energy Corp., Calgary, has a 24% interest in the Sartichala plant, referred to as the Georgian American Oil Refinery (GAOR). GAOR is near CanArgo's Ninotsminda oil field, which accounts for about 50% of Georgia's 4,000 b/d of oil production, and which supplies GAOR's crude needs.

The refinery produces fuel oil, diesel, and low-octane gasoline. CanArgo is financing a refinery upgrade that includes a new catalytic reformer, which will permit the production of high octane gasoline.

The refinery at Batumi, which mainly operates on Russian and Azeri crudes, has been running substantially below capacity as a result of a lack of oil supplies. The situation will change with the reconstruction and conversion of the 232-km Khashuri-Batumi oil products pipeline, expected to come on line in 2001.

The Chevron-financed $70 million project will permit the transport of 100,000 b/d of Kazakh oil to Batumi and free up rail transport, which is currently being used to ship Chevron's Kazakh oil from the Tengiz field. Presumably some oil will be supplied by rail to the refinery from other Kazakh sources and from Azerbaijan.

Mitsui & Co. Ltd., Tokyo, is responsible for modernizing the Batumi refinery at a cost of $250 million. Mitsui is undertaking the work without Georgian government guarantees of its investment. Marubeni Corp. and JGC Corp., both based in Tokyo, dropped out of the project because of a failure to obtain such guarantees. In 2000, a revamped, more-efficient plant at Batumi will process 50,000 b/d of crude.

Mitsui has an interest in the Agip SPA-operated Kyurdashi block in Azerbaijan. If oil is found there in commercial quantities, Mitsui may process some of its share in Batumi.

Georgia may get a new $400 million refinery in Supsa. Plans include an initial capacity of 60,000 b/d, ramping up in phases to 240,000 b/d. Azerbaijan's state oil company, SOCAR, could become an interest-holder.

A refinery at Supsa would receive oil shipments through the existing Baku-Supsa pipeline. This pipeline is expected to transport 120,000 b/d of oil in 2000 from Azerbaijan's AIOC (Azerbaijan International Operating Co.) development, and future volumes transported by this route could increase.

Itochu Corp., which would like to refine its equity-crude production from Azerbaijan in a refinery at Supsa, said it intends to be a participant in this project.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has three refineries with a total capacity of 427,000 b/d.

The Pavlodar (in northeast Kazakhstan) and Shymkentnefteorsinez (SHNOS; in south central Kazakhstan) refineries have capacities of 163,000 b/d and 160,000 b/d, respectively. They were built to process crudes from Western Siberia, delivered via the Omsk-Pavlodar-Shymkent-Chardzou pipeline.

The oldest refinery is located in Atyrau (104,000 b/d) in western Kazakhstan, close to the Caspian Sea. This is the only refinery in Kazakhstan designed to use local crudes.

In the past year, Russia supplied only 721,200 tonnes (14,400 b/d) of oil to Kazakhstan. As a result, the Pavlodar refinery which has the best processing facilities among the three plants (catalytic cracking, thermal operations and coking) has been running at 9% of design capacity.

Pavlodar has been crippled by competition from Russia's Omsk refinery (part of Russian integrated company Sibneft), located 350 km to the north. Deliveries of crude to Pavlodar plummeted after the Omsk refinery expanded its capacity to 600,000 b/d.

SHNOS was designed to process Western Siberian oil as 80% of its feedstock. Today's refinery relies largely on oil from fields operated by Canada's Hurricane Hydrocarbons Ltd. and Russia's Lukoil (Kumkol), however. It also has access to rail crude deliveries from Uzbekistan and from the Chinese National Petroleum Corp.'s Aktyubinsk fields in the west.

SHNOS processed 3.4 million tonnes (68,000 b/d) of oil (42% of design capacity) in 1999. It is currently constructing a catalytic cracking complex, which will increase its output of light oil products from 65% to 85% of its output slate.

SHNOS supplies about 65% of the refined products used in the southern regions of Kazakhstan. In 1999, the refinery produced diesel, gasoline, kerosine, and fuel oil. Close to 50% of output is consumed in Almaty.

The Atyrau refinery is in a paradoxical situation. Oil extraction in the western part of Kazakhstan is rising, but refinery output is declining. In 1998, Atyrau processed 2.7 million tonnes (54,000 b/d) of crude, or 52% of capacity. In 1999, this figure dropped to 1.9 million tonnes (38,000 b/d), or 37% of design capacity.

Built in 1945, Atyrau is the simplest of the country's three refineries. It takes crude from the Mangyshlak, Tengiz, and Martyshin fields.

The refinery requires $450 million in investments to obtain a catalytic cracker, which will allow it to process 90,000 b/d. Japanese banks are prepared to finance the upgrade, which Marubeni will undertake. The refinery revamp would boost the production of light products to 80% of capacity.

Atyrau's currently produces gasoline (A-76 and A-93), diesel, heating oil, aviation kerosine (TS-1), and fuel oil.

Kazakhstan's oil production in 1999 reached 630,000 b/d, well in excess of its nameplate refining capacity. Domestic consumption in Kazakhstan has dropped sharply from 430,000 b/d in 1990 to 130,000 b/d in 1999.

Plans have been announced for two new refineries in Kazakhstan: a $1.5 billion plant in Mangistau (150,000 b/d) and a $480 million export refinery (50,000 b/d) at the Zhanazhol field near Atyubinsk. Based on current utilization and expected growth, however, it is hard to envision support in the near term for investment in these refineries.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan has two refineries with a total capacity of 237,000 b/d. They are located at Chardzou in northeastern Turkmenistan (120,000 b/d) and at Turkmenbashi on the Caspian Sea (116,000 b/d).

In 1999, they refined 4.5 million tonnes (90,000 b/d) of crude oil, 13% less than in 1998. In 2000, the Turkmen government plans to refine 6.6 million tonnes (132,000 b/d).

The Turkmenbashi refinery is undergoing a $1.3 billion modernization, which includes the installation of a 1.8 million tonnes/year catalytic cracker by Nichimen Cos. of Tokyo and financed by Japan's Eximbank and a 750,000 tonnes/year catalytic reforming unit by France's Technip and Iran's National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC). The upgrade will also include a 1.8 million tonne/year (tpy) alkylation unit, which will be built by NIOC, an 80,000 tpy lubricants unit which may be financed by German banks, and a 90,000 tpy polypropylene unit to be built by JGC.

In April 2000, UK's Gent Oil began work on a $10.6 million project to install a desalination facility and a steam furnace to satisfy the plant's water and steam requirements. Ireland's Emerol Ltd. is currently reconstructing the vacuum unit and building storage facilities.

In the first 9 months of 1999, oil products accounted for 15% of the country's exports. This number will rise once the Turkmenbashi refinery's revamp is completed.

Oil production in 1999 reached 150,000 b/d, which is less than Turkmenistan's nameplate refining capacity. Domestic consumption of 90,000 b/d is about the same as it was in 1990.

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan has three refineries with a total capacity of 222,000 b/d.

Before the country's independence, its two refineries in Fergana (106,000 b/d) and Alty-Arik (66,000 b/d) relied on crude from a pipeline that originated in Omsk, Western Siberia and delivered oil to Uzbekistan by way of Chardzou, Turkmenistan. By 1995, these crude imports were largely eliminated, although product imports from Russia continued until 1998.

Uzbekistan achieved self-sufficiency in supplying its domestic products' demand with the August 1997 completion of a new 50,000 b/d refinery in Karaoul Bazar, 55 km east of Bukhara. It was the first grassroots refinery built in the FSU after 1991.

Along with Georgia's 2,400 b/d refinery at Sartichala (1998), it is one of two plants in this region constructed with western technology.

The Bukhara refinery was built by Technip SA, Marubeni, and JGC Corp. with Japanese participation in financing. The $400 million refinery has run on condensate produced from the Kokdumalak field, 94 km away. Kokdumalok accounts for 70% of Uzbekistan's liquids production.

The refinery is equipped with units for atmospheric distillation, naphtha hydrodesulfurization, gas oil hydrodesulfurization, kerosine sweetening, regenerative reforming, sour-water treatment, and sulfur recovery. It also has a gas plant, one control station, and two electricity substations.

It now produces gasoline for export as well as gasoline, diesel, and kerosine for the domestic market. The Uzbekistan government has plans to double the refinery's capacity.

In 1997, Mitsui and Toyo Engineering Corp. undertook a $200 million desulfurization capacity expansion project at the Fergana refinery, to permit the production of low-sulfur diesel. Texaco Inc. is involved in a joint venture to produce and market Texaco-branded lubricants from the Fergana refinery.

The third refinery at Alty Arik needs to be mothballed or completely rebuilt.

Uzbekistan is now able to export limited volumes of product by rail to neighboring countries.

Oil production in 1999 reached 190,000 b/d, which is less than the country's nameplate refining capacity. Domestic consumption of 145,000 b/d in 1999 is significantly below 1990 consumption of 255,000 b/d.

The authors-

Andrei Kalyuzhnov is a consultant in London. He has experience in engineering and procurement for process plants and design, manufacture, and assembly of machines for petrochemical and other industries. He also has been a university lecturer in mechanical engineering. Kalyuzhnov holds an MSc in mechanical engineering (distinction) from Kazak State Technical University.

Julia Nanay is a director at Petroleum Finance Co., where she provides clients with risk analyses for investments in the oil and gas industry. Nanay has worked in the oil industry in various capacities since 1976. Before joining PFC in 1985, she was a vice-president of the Charter Oil Co., a Jacksonville-based refining-marketing concern. Previous to that, she was the executive assistant to the vice-president for International of Northeast Petroleum Industries Inc., a Boston-based independent marketer. Nanay holds a BA in political science from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a masters in international relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, Medford, Mass.