Field maturity, new technology impact development off Norway

Development in Norwegian offshore areas is undergoing a shift from mature areas, which are becoming increasingly marginal, to the new "frontier" areas of Mid-Norway and the Barents Sea.

New technology and a higher number of smaller satellite fields will drive development solutions for both the mature and frontier areas in the future, concludes Wood Mackenzie in a recent report. The Edinburgh analyst notes that subsea and floating production systems are becoming standard as developments range into ever-deeper waters.

Capital investment in the Norwegian sector is expected to remain healthy for another 10 years, at the least. Reinvest ment, both by Norwegian companies and others, remains encouraging for all Norwegian shelf areas.

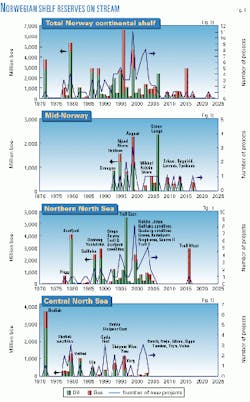

Giant oil field developments in the late 1980s made way in the 1990s for a variety of smaller, stand-alone developments, satellites, and a great increase in natural gas production. Total oil and gas reserves in the Norwegian shelf sector reached a high in the mid-1990s, exceeding 6 billion boe, then dropped considerably the following couple of years, spiking upward again in 1999 as the number of new projects jumped to 11 (Fig. 1).

While the number of developments have increased steadily over the past few years, the level of new reserves being brought on stream has decreased as established fields enter into decline. New developments in established areas are primarily satellite facilities.

Within the next decade, Wood Mackenzie said, activity in the more mature areas will most likely be restricted to these smaller satellite developments, while operations off Mid-Norway will be characterized by larger, stand-alone developments. Offshore Mid-Norway is slated to become an increasingly important gas supply area as new gas-condensate fields come on stream.

With a substantial new gas export infrastructure already in place, Norway has been increasing its supply of gas to Europe, primarily from Troll and Sleipner in the North Sea.

Key development areas

The Norwegian continental shelf can be divided into four distinct regions: the central North Sea area, the northern North Sea (Troll, Oseberg, Statfjord, Snorre), Mid-Norway (Asgard, Draugen), and the Barents Sea area (Snøhvit, Askeladd, and Albatross).

Each of these regions is distinguished by varying degrees of maturity, prospectivity, and development types.

Operators employed different solutions for efficient production in each region, and the more successful and economical of these will, no doubt, serve as a basis for future development.

Central North Sea

Norway's most mature region is its southernmost continental shelf area, the central area of the North Sea.

Discoveries in the late 1960s led to development of Ekofisk, Norway's first offshore oil development, in this area. Deliveries began in 1971. Other stand-alone production development followed-Sleipner, Valhall, Ula, Hod, and Gyda fields-with processing, transportation, and other infrastructure created to tie in these fields to a central hub.

Because the water in this area is relatively shallow, field operators opted for simple steel-jacket platforms and flare towers. More than 30 steel-jacket platforms dot the waters of this area. Today, even satellite developments such as Tambar and Freja produce from this type of production facility.

Further north in the central North Sea lies another major field, Sleipner. More sophisticated solutions were chosen to establish these later developments. East Sleipner has a large concrete gravity base structure (GBS), although West Sleipner and the smaller Loke and Gungne satellites used steel-jacket platforms.

Two small and isolated, marginal fields near Sleipner require stand-alone facilities. Varg, a satellite south of Sleipner, was developed with a steel wellhead platform and uses a floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) vessel. Production from Yme, far to the east of Ekofisk, is effected from a jack up.

Future developments in the central North Sea, Wood Mackenzie says, most likely will be relatively small and less productive than earlier ones. They most probably will be either stand-alone, FPSO-type developments or steel wellhead platform and subsea satellite developments that tie in to existing systems.

Current activity in the region focuses on enhanced oil recovery for Ekofisk and Valhall area fields and the placement of satellite facilities tying in to Sleipner.

Northern North Sea.

The large Frigg gas field was the first to come on stream in the northern area of the North Sea. It delivers gas southwestward to the UK via pipeline to St. Fergus, Scotland.

Three large concrete GBS platforms and two steel jacket platforms make up the main production facilities. Two conventional satellites were tied in during the early 1980s, and the Lille Frigg and Frøy satellites came on stream in the 1990s.

Another giant gas field, East Troll, lies in the deep Norwegian trench. Special technology led to development of the appropriate facility for this deepwater locale. Developed in the early 1990s, East Troll contains the largest concrete GBS platform on the Norwegian shelf.

In addition, a concrete semisubmersible platform with subsea well clusters and a steel semi with subsea well clusters serve West Troll oil field.

Oseberg, Snorre, and Tampen oil fields have stand-alone facilities tied in to central oil and gas export lines. The first floating production platform in Norway was used on Veslefrikk and a large tension leg platform (TLP) on Snorre, which is in relatively deep water. Stand-alone facilities are employed in a number of fields, such as Balder and Jotun, using FPSOs. Standard steel platforms, however, are employed in Grane and Ringhorne oil fields and in Huldra and Kvitebjørn gas-condensate fields.

Most future activity in the northern North Sea will be focused on the Balder-Grane area and the deepwater areas north of Troll. The Sogn area north of Troll probably will be using a floating production platform with subsea wells. Water depth will determine whether subsea developments or wellhead platforms are employed.

Mid-Norway

Mid-Norway is the new frontier. In the far northern reaches of Mid-Norway, these waters are largely unexplored, but it is expected that major discoveries are highly likely, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Initial results indicate that the area is gas-prone. Mid-Norway fields are expected to be pivotal as a new gas supply source to replace dwindling reserves in the country's older offshore areas.

Most of the existing discoveries and all the developments to date are located in the shallow Haltenbanken area where all the proven hydrocarbons are located. An integrated concrete GBS platform brought the large Draugen oil field on stream in 1993, and Heidrun field, further to the north, was developed in 1995 with a large concrete TLP platform. Gas from the field was transported to a new methanol plant in Norway via a much-needed pipeline to landfall.

Nome and Njord used floating production systems to produce oil reserves in 1997. Operators reinjected gas, as infrastructure for transporting it did not exist.

Gas export

A gas export pipeline, the Åsgard Transportation System (ATS), has finally opened up one of the largest and most ambitious offshore development projects ever undertaken.

The three Åsgard fields-Smørbukk, South Smørbukk, and Midgard-hold substantial amounts of gas.

These reserves, formerly trapped until an export option could materialize, can now be produced and delivered to the Kårstø treatment plant, where the ATS connects to the main Norwegian gas export systems that deliver to continental Europe.

Draugen, Heidrun, and Norne also will connect to the ATS, providing a gas export solution for these fields.

Mid-Norway's future

Mikkel is expected to be the first subsea development to be tied into the Åsgard facilities, followed by the South Haltenbanken development incorporating the Kristin, Lavrans, Ragnfrid, and Eriend discoveries.

A semisubmersible processing platform located at Kristin will tie back to facilities at Åsgard, and the other fields will tie in as subsea satellites. Tyrihans also will be developed as a subsea satellite to Åsgard.

Skarv, located between Heidrun and Norne, will be developed as a stand-alone FPSO development, exporting its gas via the ATS. Similarly, the Idun gas discovery could potentially be tied in as a subsea satellite to Skarv when capacity becomes availability.

The massive Ormen Lange gas field further south is slated for development as a stand-alone subsea development tied back to an onshore processing plant. That project would require a new dedicated gas export pipeline to be developed

Timing of the South Haltenbanken, Skarv, and Ormen Lange developments off Mid-Norway depends on the Troll and other gas-allocation contracts or on new dedicated sales agreements. Export capacity in the ATS also is an issue of major importance for the timing of these developments.

Barents Sea

Exploration in the Barents Sea has been limited.

Production of the substantial proven gas discoveries is hindered by the remoteness of the area.

Plans for a liquefied natural gas development have been proposed to exploit reserves in Snøhvit, Askeladd, and Albatross gas-condensate fields (OGJ, Aug. 7, 2000, p. 30).

Such a development could open potential for further exploration and satellite development of gas reserves in the wider areas.

Development types

As field development off Norway matures, the shift of marginal projects will mean a shift away from the conventional massive, fixed structures.

That is reflected in an analysis of the variety of development options facing operators off Norway:

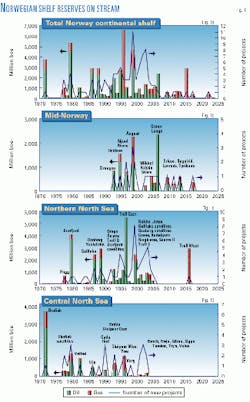

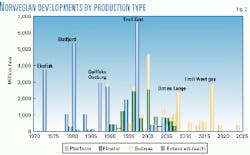

- Wood Mackenzie reported that about 40% of the facilities in use or planned in Norwegian shelf development involves the use of subsea satellite production facilities. These existing or planned subsea satellite developments represent combined oil and gas reserves totaling 13.265 billion boe (Fig. 2). These are becoming the norm in this particular environment, to accommodate both the smaller discoveries and deeper-water environments. Due to the water depths in the Mid-Norway area, satellite developments are expected to be exclusively subsea developments.

- Platforms are the second largest development choice off Norway at 37%, representing 28.662 billion boe of oil and gas reserves covered by existing and planned developments. The choice between subsea and wellhead platforms in the central North Sea and parts of the northern North Sea is partially driven by the perceived need for well workovers and intervention work due to difficult reservoir conditions. The more difficult the conditions, the more the decision is swayed toward wellhead platforms. As technology improves, the move is towards subsea developments, even in the more shallow areas.

- Deeper-water conditions frequently mandate the use of floating production facilities. Both types of semisubmersible production facilities, TLPs and FPSOs, have been employed successfully in Norwegian fields. It is thought likely that most future stand-alone developments will employ these facilities. Mid-Norway stands to benefit most from this technology. On the Norwegian shelf, floating production facilities are in use by 18% of development projects, accounting for 8.962 billion boe of reserves being produced or awaiting development.

- Extended-reach wells facilitate production in the remaining 5% of the development projects and account for about 104 million boe of reserves under production or awaiting development.

New technology

New technology issues are important for future field developments, particularly off Mid-Norway and in the Barents Sea.

The technology for subsea compressors to move natural gas long distances under water must be developed to facilitate the use of very long, multiphase, subsea pipelines off Norway.

The pipelines would deliver natural gas through deep water to onshore processing plants. This technology, at present, is not yet available.

In addition, the large South Halten banken development involves fields with extreme reservoir pressures and temperatures, challenging technological limits of subsea facilities and the commercial limits of the development.

Capital expenditures

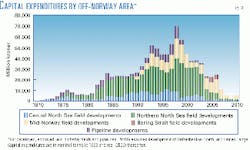

Capital expenditure on field and pipeline developments off Norway generally increased steadily up to the end of the 1990s, peaked at about 70 billion kroner in 1998, and fell sharply the following year (Fig. 3).

Most capital outlays are currently earmarked for northern North Sea developments. Much of the future expenditure on new developments is expected to be in the Mid-Norway area.

Expenditures remained flat in the central North Sea for the past decade. The importance of smaller satellite developments in mature areas, however, needs to be recognized and encouraged in order to maximize recovery and enhance the value of existing infrastructure in these areas.

Wood Mackenzie's evaluation is that capital investment in the Norwegian sector is likely to remain at a healthy level throughout the coming decade, with much of it concentrated in the Mid-Norway sector.

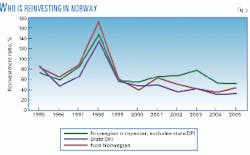

In Fig. 4, Wood Mackenzie calculates a ratio representing the average capital expenditure (including exploration and appraisal costs) compared with "disposable income," which is net cash flow plus capital expenditure. The level of reinvestment is relatively healthy and considerably higher than for the UK, where reinvestment currently averages only about 20-25%. The high level of reinvestment in 1998 was a result of the record level of investments, high exploration activity, and a low oil price, resulting in poor net cash flows.