Risk management, financing availability keys to winning in Caspian region

Wood Mackenzie has conducted a two-part review of the upstream Caspian Sea region. In this first part, Wood Mackenzie analysts review exploration acreage, reserves, and maximum oil and gas production potential scenarios to 2020; rank the international companies in the region on these key parameters; and draw conclusions about the ultimate winners in the region.

In the second part, scheduled to run in the Aug. 21 Oil & Gas Journal special report, Caspian Sea Activity, Wood Mackenzie addresses the investment required to meet these optimistic production potentials and applies risk factors to these upstream parameters to arrive at a more realistic scenario for future production.

As the balance of power swings back and forth across the Caspian Sea region, Wood Mackenzie has undertaken an analysis that examines and ranks the reserves and production potential of four key Caspian countries: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

At a corporate level, the rise of the supermajors in 1999 means that the bulk of the high-profile opportunities lie in their hands, although there are some exceptions. Several majors are notable by their absence, while some relatively minor global players have survived the highs and lows of 1999 to hold on to profitable, if slightly lower-key, exploration and production assets.

While we can identify the key players in the Caspian in the short term, it is ultimately the companies that can secure the necessary financing and effectively manage the technical, commercial, and political risks in the region that will unlock its full potential.

Reserves

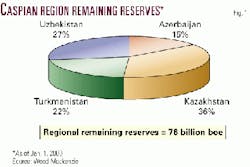

The four key Caspian countries examined in this article had remaining oil and gas reserves of 76 billion boe as of Jan. 1, 2000 (Fig. 1). This consisted of 275 tcf of gas (almost two-thirds of the total on a barrel of oil equivalent basis) and 27 billion bbl of liquids. These combined reserves exceed those of Western Europe, which totaled about 60 billion boe as of Jan. 1, 2000 (24.5 billion bbl of liquids and 196 tcf of gas).

Although Kazakhstan leads the list of Caspian liquids reserves holders, it comes closest to a balance between oil and gas reserves, holding 56% of the region's oil and 25% of its gas.

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are the dominant players in the gas sector, with 67% of the region's remaining gas reserves. Their overall importance is reduced, however, by their comparatively low liquids reserves-managing only 15% of the regional total between them.

Even with the addition of 500 million bbl of liquids and 14.1 tcf of gas from the Shah Deniz project, Azerbaijan is still placed fourth in terms of overall remaining reserves, with 15% of the regional total. Despite the size of the Shah Deniz gas reserves, Azerbaijan remains a more significant player in the oil sector for the time being, with 28% of the region's oil but only 8% of its gas.

Liquids production potential

Liquids production from the Caspian region could reach almost 4 million b/d by 2015-triple the expected production of 1.3 million b/d in 2000 (Fig. 2, Table 1).

By 2020, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan are expected to dominate regional production and contribute 1.1 million b/d and 2.5 million b/d, respectively, to the total. However, a significant part of this potential in both countries is tied to the success of some key offshore exploration projects.

In Kazakhstan, although production at both the Karachaganak and Tengiz projects will probably be in decline by 2020, this is expected to be offset by increasing production from the OKIOC consortium's Kashagan discovery (OGJ, May 22, 2000, Newsletter) and some new exploration success. A controlled but steady growth in demand of around 3%/year should allow increasing volumes of Kazakh oil to be exported, building to about 2 million b/d by 2015).

Similarly, Azerbaijan's key projects of Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli and Shah Deniz should also be past their peak by 2020, with overall country production following a similar trend. This reflects the likely bias towards gas discoveries in the offshore. The Azeri liquids production decline may be delayed slightly if gas discoveries have significant associated condensate.

It is expected that Turkmen liquids production will also be in decline by 2020, with all operational foreign projects (Zhdanov, Nebit Dag, Livanov, and Garashsyzlyk-2) having come off plateau by 2015. New exploration projects should contribute to overall country production by this point but not in sufficient volumes to stop the production decline.

In terms of self-sufficiency, Uzbekistan is probably in the most precarious position. Unless considerable efforts and investment are made in exploration in the near future, the country risks becoming a net oil importer again by 2005. By 2020, even assuming a very modest 1%/year growth in consumption, Uzbekistan may need to import over 100,000 b/d of oil.

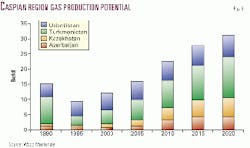

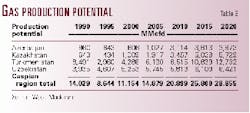

Gas production potential

By 2020, the Caspian region could be producing almost 29 bcfd of gas, mostly from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (Fig. 3, Table 2). Unlike liquids production, regional gas production is still expected to be on an upward trend in 2020, with the strongest proportional growth during 2000-20 being registered in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan.

The potential growth in gas production is significant, but is also highly dependent on producers securing convenient gas markets in a region where potential gas supply looks likely to substantially outstrip demand within a decade. Obtaining the finances to build gas export pipelines and managing technical and political risks are other factors that will need to be addressed.

The growth in Kazakhstan's gas production potential can be attributed mainly to the Karachaganak, Tengiz, and OKIOC projects, all of which should allow the gas plateau to be maintained at over 25 bcfd beyond 2020.

Azeri gas production should peak in 2015-20, in line with Shah Deniz production, and be in the early stages of decline by 2020. However, development of the Absheron and Nahchivan projects should partially offset this.

Turkmen gas production will be driven by market availability rather than by production capacity. If Turkmenistan is to meet the potential production profile as indicated by Wood Mackenzie (which is considerably less ambitious than the Turkmens' own plan), then both Turkish and Far Eastern markets will have to be secured for Turkmen gas. Similarly, a lack of access to export markets means that Uzbek gas production will probably reflect internal demand rather than production capability.

Companies' liquids production

Wood Mackenzie's production and reserve estimates for active projects involving the main foreign participants in the Caspian have been combined to provide the following company analysis (Table 3).

Caspian oil production in 1999 was dominated by a handful of companies that have interests in only a few large fields in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan: Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG), Tengiz, and Karachaganak. These three fields alone contain 47% of the region's remaining liquid reserves and 15% of the gas reserves.

With a 45% interest in giant Tengiz field, Chevron Corp. leads the way in current liquids production with 87,750 b/d in 1999. Chevron is likely to remain at the top of the production rankings for several years to come as Tengiz ramps up to a peak production of 700,000 b/d by 2015. In 2015, it is estimated that Chevron will be producing a net 315,000 b/d (over 8% of the Caspian region's projected liquids production), primarily from Tengiz field.

With interests in projects that are at early stages of development, both ExxonMobil Corp. and BP Amoco PLC have the potential to realize liquid production levels similar to Chevron's by 2015. It is estimated that, by 2015, more than 57% of the Caspian liquids production will come from just four fields: ACG, Tengiz, Karachaganak, and OKIOC (Kashagan).

Smaller companies, such as Ramco Energy PLC and Delta/Hess (K&K) Ltd. (Amerada Hess Corp. and Delta Oil Central Asia Ltd.), that have small interests in some of the largest Caspian projects have relatively high liquid production rates given their size. Their net production rates look set to increase over the next 10 years, as projects such as ACG mature and production reaches plateau. For these smaller companies that aggressively focus on the Caspian region, such projects form a material part of their overall global business, reflecting a high-risk strategy.

Other smaller companies such as Frontera Resources Corp., Houston; Whitehall Corp., Dallas; and Turkey's Petoil choose to participate only in those onshore projects (Kursanga-Garabagly, Kamaled- din, and Kurovdag) where costs are lower and the overall financial and technical risks are less. For these companies, 1999 liquid production rates are more modest at around a net 1,000-2,000 b/d. These companies are more in control of their projects and are therefore able to manage their risk more effectively.

Companies' gas production

Agip SPA and BG PLC top the 1999 gas production rankings with net production of 97.5 MMcfd each from their 32.5% interests in giant Karachaganak gas field, while Chevron comes in a respectable third with 91 MMcfd of associated gas production from giant Tengiz field (Table 4). With both fields in the early stages of production, Agip, BG, and Chevron's future gas production looks set to rise as the fields' plateaus are reached around 2015. It is estimated that Agip, BG, and Chevron will have the combined capability to produce 2.29 bcfd by 2015 (9% of the projected Caspian gas production).

For foreign investors in the Caspian region, securing gas contracts, export capacity, and managing risk remain the main obstacles for commercial projects. With Turkey, the main gas market in the region apparently has signed a number of gas supply contracts in recent years, so there remain few opportunities for companies to sign large gas contracts in the near future.

Turkmenistan remains hopeful that an agreement can be reached with Azerbaijan over the allocation of capacity for the proposed Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) to Ceyhan, which would see value realized from their huge gas reserves. However, it looks increasingly unlikely that the TCGP will move forward, given that the Russian gas market appears to be opening up for Turkmenistan. Azerbaijan is also unlikely to accommodate such a project (which would need to be constructed on Azeri territory), as this undermines the possibility of Azerbaijan selling its growing gas reserves to the Turks.

With gas production in the Caspian likely to be driven by market availability rather than by production capacity, future production profiles will depend heavily on which projects secure a share of the limited gas markets. BP Amoco's Shah Deniz gas project is well-positioned to obtain a share of the Turkish and Azeri gas markets. With a projected gas production capability of 500 MMcfd in 2015, BP Amoco looks set to climb the gas production rankings in the near future. Similarly, Statoil's interests in ACG and Shah Deniz should see its net gas production rise 80-fold, from 5.2 MMcfd in 1999 to 430 MMcfd by 2015.

Ranking the companies

Major companies noticeable by their absence from the Caspian production rankings include Royal Dutch/Shell, Conoco Inc., TotalFinaElf, and Phillips Petroleum Co. (Tables 3-4), These companies all have prospective acreage in the Caspian region but have yet to establish commercial production.

Shell in particular is keen to build a strong gas exploration position specifically in Turkmenistan, to complement its 50% interest in the proposed TCGP.

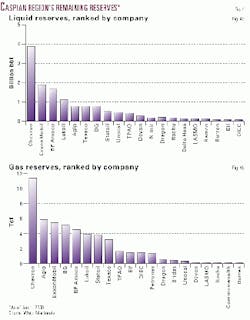

The ranking of companies by remaining reserves closely reflects the production rankings, with Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP Amoco, and Russia's Lukoil dominating (Figs. 4a-4b). Chevron tops the table with net remaining reserves of 3.917 billion bbl and 11.4 tcf from giant Tengiz field. BP Amoco's large Caspian reserve base of 1.677 billion bbl and 4.493 tcf is held within the two giant Azeri projects, ACG and Shah Deniz.

The combined remaining reserves for Chevron, Lukoil, ExxonMobil, and BP Amoco equates to over 13 billion boe, which represents almost one fifth of the Caspian region's remaining reserves (as of Jan. 1, 2000).

For the major oil companies, the Caspian region forms a significant part of their global reserve base and remains a focus for significant future reserve additions. The remaining Caspian reserves are predominantly controlled by state organizations such as SOCAR, Kazakhoil, and Turkmenneft.

Company acreage positions in the Caspian are not dominated by those major oil companies that top the production and remaining reserves tables (Table 5).

The Japan National Oil Corp. consortium tops the rankings with 25,000 sq km of exploration acreage in Kazakhstan. Shell, Kerr-McGee Corp., and Amerada Hess lie somewhat behind JNOC with about 12,000 sq km of exploration acreage each. It is noteworthy that four out of the five top-ranked companies by net acreage currently have no oil or gas production in the region.

Both ExxonMobil and BP Amoco currently hold well-balanced positions with a strong mix of production and exploration acreage. Chevron, on the other hand, only has interests in the Absheron exploration block in which to build on the Tengiz reserve base.

Ultimate winners

Who will ultimately succeed in the Caspian?

The previous ranking tables provide a useful indicator of the "key to success" in the region, in the short term.

However, they do not indicate which company will move quickest to consolidate its strategy in the region, which company will develop the strongest position in the long term, or which company will ultimately be the most profitable.

Whichever projects are pursued by the companies, the availability of finance and the sophisticated management of risk in this volatile region will ultimately be the key success factors and will separate the weak from the strong.

The authors

Hilary McCutcheon has worked at Wood Mackenzie for 4 years since graduating with an MA degree in Russian interpreting and translating. She has been involved in coverage of various parts of the former Soviet Union (Central Asia, Caucasus, and Timan-Pechora) and now focuses on commercial analysis of Central Asia.

Richard Osbon has a BSc degree in geochemistry from the University of Manchester and an MSc degree in basin evolution and dynamics at the University of London. He worked for ARCO British Ltd. as an exploration geologist working the UK North Sea before joining Wood Mackenize in January 2000, where he now works as a research consultant on the Former Soviet Union team.