Foreign Companies In Nigeria's Niger Delta Scramble To Implement Security, Stakeholder Initiatives As Situation Threatens To Worsen

As high-risk a region in the oil-producing world as there is, Nigeria's Niger Delta is threatening to get worse.

With its long history of intertribal feuds, poverty, disease, unemployment, crime, violence, political corruption, and environmental degradation, the Niger Delta could stand as the poster child for High-Risk Operations.

And a string of incidents dating to the previous government's execution of local dissidents has cast a global spotlight on the region, with the oil companies operating there caught center-stage.

Tensions have escalated in recent months despite the promise of reforms by the new government, spilling over into internecine violence that has claimed hundreds of lives and disrupted oil operations in a region that provides the bulk of production for one of the world's leading oil exporters.

The new government of President Olusegun Obasanjo has taken some steps to reverse the decades-long record of neglect and corruption that has marked the central government's stance toward an impoverished region that holds not only the bulk of Nigeria's oil reserves but also its critical LNG export project. And oil companies, caught in the crossfire of bullets among warring factions and in the barrage of internet-and-fax campaigns by international pressure groups that target their operations, are stepping up efforts to bolster stakeholder relations initiatives.

Whether such efforts succeed in improving the outlook for this benighted region and perhaps thereby improve the outlook for foreign oil company investment there-or prove ineffectual in stopping a slide into chaos and civil war-might well become clear this year. The unlikeliest scenario is that the status quo will remain. The likeliest scenario for foreign oil and gas companies is that things either will get gradually better or quickly get much, much worse.

Background

The Niger Delta region is one of the world's largest wetlands areas, covering about 70,000 sq km of mangrove swamp amid upland and lowland areas.

Nigeria became an important oil-producing country soon after a joint venture of Royal Dutch/Shell and the then-British Petroleum Co. PLC found commercial volumes of oil in the Niger Delta region in 1956. It was scarcely a decade thereafter that Nigeria erupted into civil war (1967-70), after the oil-rich Eastern Region seceded in a dispute that was mainly over the region getting a bigger share of government oil revenues but also underlain with ancient ethnic and religious conflicts.

That there is widespread environmental degradation in the Niger Delta region is without dispute. But while activists seek to blame the multinational oil companies for the environmental damage, the oil companies are quick to point to commonplace sabotage of industry facilities-such as the 1998 Jesse pipeline explosion that claimed more than 2,000 lives-as a major culprit for the region's environmental woes. Adding to the environmental damage from frequent oil spills has been the routine flaring of natural gas in the region, which industry and the government have sought to reduce from levels that long held at 100%.

After Nigeria nationalized BP's Nigerian holdings in 1973 (in retaliation for what it alleged were BP's indirect sales of oil to the apartheid government of South Africa), Shell Petroleum Development Co. (SPDC) became the dominant foreign petroleum company in Nigeria. It was soon joined by Nigerian Agip Oil Co., Texaco Overseas Petroleum Co. Nigeria Unltd., Elf Petroleum Nigeria Ltd., Chevron Nigeria Ltd., Mobil Producing Nigeria Unltd., and the LNG export joint venture Nigeria Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG).

Unrest growing

Much of the unrest in the Niger Delta region has centered on a handful of large ethnic groups-notably the Ijaw-that live in miserable conditions eking out a subsistence existence while being excluded from the decision-making process of a central government ruled by larger, rival ethnic groups.

Irked by the abject poverty, massive unemployment, absence of social amenities, minimal economic infrastructure, and the lack of remedial compensation for environmental degradation, scores of Ijaw youths have resorted to violent agitation in the region. The problems have ranged from thievery and sabotage to kidnapping and murder.

Compounding an already nettlesome situation has been an increase in activity by criminal elements seeking to take advantage of the chaotic situation by embarking on campaigns of sabotage and seizures of oil production facilities and hostage-taking and kidnapping of expatriate oil company workers-all intended to garner extortion or ransom money. Between April and December of 1999 alone, about 30 oil company workers were kidnapped.

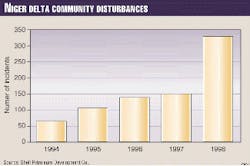

SPDC operations have virtually ground to a halt for almost 3 years in the Ogoni region because of escalating unrest there. The Shell unit in 1998 recorded about 325 attacks on its facilities in the Niger Delta (see chart).

A sampling of other such incidents include:

- Elf in October 1999 lost at least 100,000 b/d of crude oil production following attacks on its operations by locals in the Obite and Obagi areas of Rivers state; it was told to leave the area within a week unless it met a demand to increase local employment. Elf, which supplies 23.33% of the NLNG project's 26.6 million cu m/day of gas feedstock, had its facilities shuttered for several weeks.

- The Ikebiri youths of Bayelsa state seized and shut down Agip's western oil pipeline to the Bonny export terminal over nonpayment of $100,000 the youths had demanded for compensation.

- SPDC and Agip were asked to leave the Egbema area of Rivers State in August 1999 by local communities citing poor company relations.

- In December 1998, a group of Isoko youths attacked the SPDC accommodation facilities in Olomoro Oleh oil field, and a guard was killed.

- In 1998, 10 SPDC staff were abducted by armed men from the Peretorugbere community in the Ekeremor area of Bayelsa state; they were released after 8 days through the intervention of prominent community leaders.

- Texaco in September 1999 signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Bayelsa state government and seven communities in the state calling for the payment of $2.5 million in compensation for an oil spill resulting from a ruptured pipeline to the Ijaw community; that is in addition to $50,000 already paid to the community of Ughel* in Delta state as "compassionate compensation" to Bayelsa claimants living outside Bayelsa state.

- A US expatriate, Danny Bukfin, and a Nigerian, F. Tarigha, were abducted from Chevron's Kula base in the Akuku-toru area of Rivers state; Tarigha was later released, but a ransom demand of $150,000 was issued for the release of Bukfin.

- Two Wilbros expatriate workers were kidnapped by Egbesu-self-described as a "human rights" organization consisting of Niger Delta youths-and later released after payment of ransom.

- A US expatriate employee of Agip was kidnapped and held for $1,150,000 in ransom.

- Two Bristol Helicopter pilots were taken hostage from SPDC's Enwhe flow station by unidentified youths seeking a $100,000 ransom.

Preventive measures

Oil and gas companies have undertaken a number of preemptive measures seeking to stem the rising tide of crime and violence targeting their personnel and facilities in the Niger Delta. But even such good-faith efforts can be difficult to implement.

Before the NLNG project construction began, the JV operating the project signed an MOU with the community of Bonny, agreeing to provide piped water, roads, and electricity to the local residents. That has not been carried out because of delays in commissioning the new project-originally scheduled for Nov. 25-that the operator blames on security concerns following outbreaks of violence by local youths. This has led local and state leaders to hold a series of meetings with the project operator in an effort to stave off further outbreaks of violence.

Other companies have sought to beef up their local security forces by employing locals in their respective host communities to guard their facilities. SPDC has hired a number of Nembe youths to guard some of their facilities in Bayelsa state. Such local security forces themselves have been involved in battles with armed bandits and kidnappers. In April 1999, hostages held by an unidentified group were rescued by Bayelsa state youths in a bloody clash that left three kidnappers dead. In the Amassoma community of Bayelsa state, local security forces lynched six men suspected to be pirates in their community.

While beefing up security, oil companies have also undertaken steps to improve stakeholder relations with local communities, putting community development at the top of their priority list in the Niger Delta.

SPDC, for one, has embarked on a regional initiative to improve the quality of life in host communities by establishing a community development program in concert with local leaders, the central government, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

SPDC's program entails a policy of encouraging the full participation of host communities in project planning, implementation, and monitoring; maintaining communication with all social segments of host communities in order to address their needs; and focusing community development assistance on activities with the greatest impact and broadest benefits for the host population-paying special attention to the most economically disadvantaged social group.

Niger Delta operators also are opening dialogues with local agitators to address underlying problems rather than requesting an increase in government security forces when violence breaks out-a step that in itself can set the stage for even worse violence later.

The foreign multinational firms operating in the region now recognize that a better approach than the piecemeal, often-superficial measures of the past calls for pursuing long-term goals in partnership with the communities participating directly in sustainable development initiatives-with an emphasis on self-reliance.

That latter point is crucial in a nation with severe unemployment, particularly among its youth. The emphasis in the Niger Delta is on helping youths acquire the skills needed to set up their own small businesses. For example, about 235 Nembe youths last year benefited from an SPDC program that taught such skills as welding and metal fabrication, woodworking, carpentry, electrical installation, and plumbing.

Similarly, Agip in May 1999, commissioned a $2.5 million adaptive skills acquisition program for youths in the Ogba-Egbema-Ndoni ethnic enclave of Rivers state.

Some of the oil companies have recognized that lack of finance is the key inhibitor to business development and self-employment in rural areas and have implemented micro-credit and related business development schemes with the aim of helping revive the economy of host areas.

Companies also are introducing pipe-borne water projects to alleviate the critical water and sanitation needs of the Niger Delta rural poor.

Other initiatives entail expanded agricultural support programs, construction of roads, award of scholarships, and implementation of health-care systems in a number of communities throughout the Niger Delta.

Environmental initiatives

Just as critical as the self-help economic programs are the oil companies' environmental initiatives in the Niger Delta-both to remediate past pollution and to minimize new pollution.

A key step is upgrading facilities to minimize potential for releases of hydrocarbons into the environment, notably schemes to reduce gas flaring.

Companies are undertaking efforts to achieve 100% compliance with the Department of Petroleum Resources guidelines and standards that call for zero flaring by 2008. Efforts at eliminating harmful air emissions include upgrading flow stations, working over and cleaning up existing wells that might be emitting hydrocarbon vapors, and phasing out halon gases. Initially, gas-flaring reduction has focused on renovating damaged flares and installing knockout drums in all problem flow stations with the sole aim of conserving, reinjecting, gathering, and harnessing the associated gas.

Meanwhile, companies are stepping up efforts in the area of waste management by establishing permanent, environmentally benign landfill sites and cleaning up the current stockpile of chemical wastes and oily sludge.

Oil companies are also trying to reduce the "footprint" of their operations in the delta region, opting for horizontal drilling, which reduces the number of wells; cluster-drilling from a single wellpad to minimize land use; and re-siting of well locations to reduce the length of access roads or canals.

In addition, oil operators are drawing up plans to decommission installations, including the removal of facilities and site restoration and monitoring after closure. And an effort is under way to eliminate the use of oil-based drilling muds.

The latest approach to Nigerian oil field development centers on planning for minimal environmental impact by treating and disposing of waste products according to the latest international standards and treating and disposing of produced water with regard to minimal surface and subsurface risk.

In addition to cleaning up past oil and chemical spills, delta operators have joined to draw up spill response contingency plans that allow for a timely, coordinated response. Oil companies in the delta must agree to maintain records of all waste streams, covering their management and disposal.

Shell is trying a systematic approach in implementing its environmental policies in the Niger Delta. SPDC conducts environmental impact assessments and environmental evaluation reviews for all aspects of the natural and social environment that may be affected by its activities. This approach also entails regular consultation with and monitoring by all affected stakeholders and a pledge to restore operating sites to their original state after operations have ceased.

SPDC is also implementing a company-wide remediation program that will inventory all of the company's past operating sites. A project team that conducted a portfolio assessment in 1998 is presently using a risk-based methodology to prioritize the sites for remediation with respect to health, safety, and environmental risks. Among the techniques the Shell unit is using to restore its oil-contaminated sites is state-of-the-art bioremediation.

Such measures are essential for oil and gas operators that want to remain in business in the Niger Delta, despite the region's plethora of troubles. Some companies have placed high hopes on Nigeria's deep waters, where a number of giant field strikes have been made in recent years, and it behooves them to put their best foot forward in other parts of Nigeria if they are to retain access to the country's prolific new offshore plays. For instance, Agip plans to increase its Nigeran oil production to 160,000 bo/d by yearend 2000 and to expand its presence in the country with the acquisition of acreage both onshore and offshore. The company contends it can best accomplish those goals by repositioning itself as a leading player in the Nigerian industry by working with the federal, state, local government, and community leaders to improve the quality of life for the residents of the Niger Delta.

Given the stakes involved-at the least the potential for further disruption of Nigerian production and at the worst an all-out civil war that might close off this highly productive and highly prospective country to foreign investment for years to come-there is little alternative for foreign oil and gas companies.