Third oil shock: real or imaginary?

Crude oil prices rose from $10.90/bbl on Mar. 10, 1999, to $33.92/bbl exactly 1 year later. The price increase moved the issues of US energy policy briefly from the back pages of the business section to the front page. However, the attention was brief.

By early April, prices had declined by one-third and attention shifted to Microsoft, tax cuts, the election, and the stock market. Oil was quickly banished again from the public eye. No doubt, everyone hopes it will stay out of sight for another 10 years.

The topic will return to the front pages soon, however, because the world may be confronted by a third oil shock. This third upset promises to be similar to but have a more modest economic impact than the two previous incidents, which occurred in 1973 and 1979. As in 1973 and 1979, the causes of this crisis will be a reduction in OPEC oil production and stagnation in non-OPEC production taking place at a time of rapid economic growth.

As in 1973 and 1979, some oil producers can be expected to exercise market power to boost prices. As in 1973 and 1979, the price increases can be expected to slow economic growth, although the impact will be muted.

Still, the current episode could be very different from its earlier cousins, because consuming nations now have the means to moderate its effect. Industrialized nations hold more than 1.2 billion bbl of strategic stocks, worth about $30 billion today.

By lending these stocks to the market through policies identical to those employed by central banks, the G-7 countries can make the third oil shock a nonevent and avoid any of the potential economic disruptions.

Third oil crisis

The world experienced two oil shocks during the last 30 years. The first occurred in 1973 following the Arab-Israe* war. The second took place in 1979 following the Shah of Iran's fall from power. It can be argued that a third oil shock began in March 1999 and is now gaining momentum.

To defend this assertion, it is necessary to describe with some precision the meaning of the term "oil shock." For economic purposes, an oil shock is defined here as an increase in oil prices large enough to cause a worldwide recession or a significant decline in global economic activity. Here, "significant decline" is defined as a reduction in the growth of real GDP below projected rates by 2-3 percentage points.

The 1973 and 1979 episodes both qualify as oil crises by this definition. Economists Edward Fried and Charles Schultze assert that the oil crisis caused a decline in GDP of 4.7% in the US, 2.5% in Europe, and 7% in Japan.1 According to the US government, the 1979 increase in oil prices caused world GDP to drop by 3% from the trend.2

Critical preconditions for oil crises

The 1973 and 1979 crises shared three key characteristics. First, the disruption in oil supplies occurred at a time when the world economy was expanding at a rapid rate. The quick economic growth stimulated greater use of petroleum. Second, both disruptions occurred when the world's crude oil capacity was being stretched to the limit.

Third, each crisis took place at a time when investment in oil and gas exploration had tapered off, making it impossible to achieve a speedy increase in non-OPEC output.

For example, the 1973 crisis occurred at the end of a period of rapid growth in US petroleum consumption. The increase was fueled by strong expansion in gasoline consumption and a wave of electric utilities substituting oil for coal. This growth in demand came about simultaneously with the peaking of domestic oil production from fields in the Lower 48.

In 1973, state regulators in Texas, Louisiana, and several other states lifted all constraints on output imposed on producers in their states.3 Even so, US dependence on petroleum imports rose rapidly.

A 1970 study by a federal cabinet task force had noted a projected increase in US dependence on imports and forecast the need for increased volumes of exports from the Middle East. This study calculated that, by 1980, Middle East crude output would need to rise to not 20, but 30 million b/d to meet world needs.4

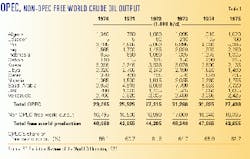

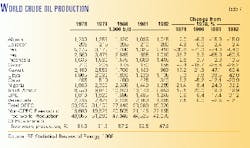

The squeeze on supply occurred in 1973. World oil production outside the Soviet Union rose from 42 million b/d in 1971 to 44 million b/d in 1972 to 48 million b/d in 1973 before dropping slightly in 1974. In Saudi Arabia, output jumped from 4.5 million b/d in 1971 to 5.7 million b/d in 1972 to 7.4 million b/d in 1973 and to 8.3 million b/d in 1974 (Table 1.) In these years, the market demand for OPEC exports created the foundation for the crisis.

Obviously, the Middle East's production never approached 30 million b/d. Instead, crude oil prices rose sharply, world economic growth stopped, and demand for oil shrank. The first oil crisis became part of historical lore.

The second oil crisis had slightly different origins. Through the late 1970s, oil-exporting countries boosted production and made an effort to "stabilize" nominal oil prices. This effort ended with the December 1978 OPEC meeting. Following the assembly, OPEC announced a 15% price increase to be phased in over 12 months.5 At the time, producers stated that they were forced to boost prices because demand was growing rapidly, because Western currencies (particularly the dollar) were weakening, and, implicitly, because the organization had market power.6

The price increase marked the beginning of the second crisis. The principal cause of the predicament, though, was the fall of the Shah of Iran and the subsequent outbreak of war between Iraq and Iran. After the coup, Iran's production plunged from 5.2 million b/d in late 1978 to only 1.4 million b/d in 1980, removing 6% of world production from the market.

Output remained low for over a year. Some of this volume could have been made up by more production from other countries, particularly Saudi Arabia. However, such increases from other nations were irregular, and prices surged. Production then fell again, in September 1980, when the war between Iraq and Iran erupted.

Unlike the first crisis, the second calamity coincided with a large drop in OPEC production. OPEC output decreased from 31.4 million b/d in 1979 to 27.4 million b/d in 1980, primarily because of problems in Iran.

The increase in oil prices slowed world economic activity dramatically. High interest rates in the US, recession, increased production from non-OPEC sources, and drastic changes in patterns of energy use trimmed demand for OPEC exports and ultimately obliterated the impact of the second crisis.

The 1980 Economic Report of the President put the change succinctly: "In 1980, following a second major rise in oil prices, economic expansion again came to a halt. It is abundantly clear that price shocks of the size experienced in recent years cannot be absorbed without serious strains and disruptive side effects: real incomes are squeezed, inflationary forces are intensified, and monetary policies cannot substantially offset or counteract all of these effects."7

The third precondition for a crisis is the lack of sources for immediate increase in supply outside OPEC. Such a supply boost might be called a "fortuitous increase," because it must occur by accident. Long lead times in the investment and development cycle make it impossible for companies to boost production quickly.

In both 1973 and 1979-80, the world's energy industry was at the end, rather than the start, of a new surge in non-OPEC output. In both instances, the investment slowdown could be attributed to the pernicious effects of economic regulation in the US and Europe. This effect is most visible in the first crisis (Table 1), which saw non-OPEC free world production actually decline from 1973 to 1975.

Preconditions for oil crisis

The three conditions that made the 1973 and 1979 oil crises possible have been met today. First, world consumption is growing rapidly and is projected to continue expanding. Second, every indicator points to the fact that production from OPEC will not rise substantially.

Finally, investor excitement over technology stocks and abhorrence of traditional industries have depressed oil equities. Consequently, firms in the oil industry are limiting their investments, preferring instead to buy back stocks.

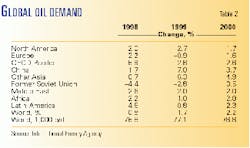

The increase in world consumption has been chronicled by the International Energy Agency and the US Department of Energy. IEA's May 2000 forecast anticipates a 2.0% increase in consumption, which follows a 1.6% increase in 1999 and a 0.6% rise in 1998 (Table 2).

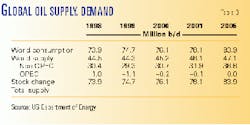

DOE projects a further 2.6% increase in worldwide consumption in 2001. This forecast presumes that the global expansion continues and that world oil prices stabilize at roughly $20/bbl.9 The agency's International Energy Outlook 2000 forecasts an additional 1.8% increase/year to 2005.10 Over half of the increased output must come from OPEC sources, as can be seen in Table 3.

The DOE forecast-and other projections-presumes that increased supplies will be available at current price levels (or any price level, for that matter.) Obviously, if they are not, the projected consumption levels will not be available.

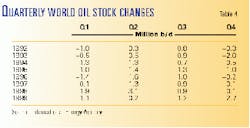

Supplies of petroleum can come from two sources: production from the ground or liquidation of inventories. Traditionally, demands are met from both sources over the course of a year. Inventories tend to increase during the spring and summer, while being liquidated during the fall and winter. IEA's estimates of the quarterly pattern of inventory fluctuations are shown in Table 4.

Potential inventory draws

Inventories will not be able to play their traditional role as a source of supply during the fall of 2000 and winter of 2001. Indeed, absent a recession, stocks may not be able to play a role as a source of supply for several years because the cuts in supply have essentially drained the world of all available commercial holdings.

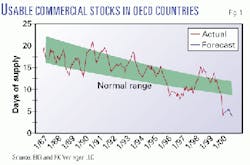

The decline in stocks is shown in Fig. 1, which shows the trend in usable commercial days of supply in OECD countries. Usable commercial days of stocks represent volumes of oil held in excess of the minimum operating inventories (MOI) required to assure the uninterrupted operation of the petroleum industry.11

Also shown is a one-standard-deviation range in the trend. It may be observed from Fig. 1 that OPEC's decision to cut production in March 1999 has forced usable commercial stock coverage to record low levels. This trend is also observed outside of the OECD.

The draw on stocks caused by the producers' March 1999 cutback effectively removes inventories as a source of supply over the next 12 months absent a dramatic rise in production during the second quarter of 2000. There is no indication that OPEC's March 2000 meeting will permit such an increase in stocks.

The likely pattern of world petroleum supply and demand over the next 15 months is illustrated in Table 5, which shows a projection of world consumption by region, non-OPEC supply, and OPEC supply.

The key lines in Table 5 are those showing the projected production by OPEC countries and the change in total inventories; these two are inexorably linked together. Traditionally, the forecast of stock changes falls out after the analyst projecting world petroleum supply and demand inputs a guess at OPEC production levels. However, as noted above, inventories today are at minimum levels. Thus, in the current circumstance, an analyst preparing a supply-and-demand balance must insert a level of OPEC production that at least assures no further decline in inventories.

As can be seen in Table 5, OPEC crude production must rise from current levels of 26.5 million b/d in the first quarter to 27.9 million b/d in the second, 28.2 million b/d in the third quarter, and 30 million b/d in the fourth quarter, if projected levels of consumption are to be realized.

Possible OPEC production levels

Future levels of OPEC supply depend on two factors: capacity to produce crude and willingness to use the capacity. For the last 10 years, OPEC members have had adequate capacity and, with the exception of 1989 and 1999, have demonstrated a willingness to operate it.

The situation will change by the fourth quarter, when available capacity will essentially be equal to projected demand.

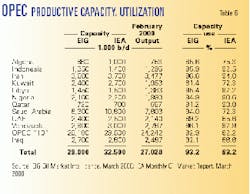

Table 6 presents two estimates of OPEC's crude oil productive capacity. The first is taken from the Energy Intelligence Group's publication Oil Market Intelligence. EIG defines its term "capacity" as being "attainable within 30 days and sustainable for 3 months."12 The second estimate was published by IEA.13

The agency does not explain the basis of its figures. Also shown in Table 6 is an estimate of February output for each of the 10 OPEC members, as well as rates of capacity use.

Three observations emerge from this table. First, most of the OPEC countries listed exhibit high rates of capacity use (eight, including Iraq, are at over 90% by EIG estimates and six by IEA calculations). Second, according to the EIG assessment, OPEC lacks the capacity to meet the projected production level of 30 million b/d in the fourth quarter.

Finally, Iraq's participation will be required in the fourth quarter to balance the market, even under IEA's more optimistic projection of capacity.

The second and third observations are very troubling. According to the calculations presented in Table 5, OPEC must produce roughly 30 million b/d in the fourth quarter to maintain a supply-and-demand balance under the current low level of stocks. Yet according to estimates of OPEC productive capacity, an output level of 30 million b/d may either be beyond the organization's reach or, if it is feasible, only achievable with production from Iraq.

Given this information, a report published in the Energy Compass on Mar. 31, 2000, is exceedingly troubling.

"Iraq intends to ramp up its production by about 1 million b/d by the end of the year to curry favor with the US, even if it means permanently damaging its reservoirs," Iraqi Oil Minister Amir Rasheed told the publication.

But if Washington does not play ball in reaching a compromise on the implementation of a United Nations resolution that would permit foreign investment in Iraq's oil sector, Iraq will shut down production, depriving oil markets-and US voters-of at least 2.4 million b/d of supply.14

Examining this offer reveals that Iraq plans to use OPEC's March 2000 agreement to maximize good will while not affecting inventory levels. In contrast, its threat to cut production would come at a time when other producers would lack the surplus capacity to offset this action.

Iraq's proposal to boost production to "curry favor" with the US will do nothing to replenish stocks, because OPEC members have instituted a system to prevent restocking. In a little-noted footnote to the March 2000 meeting, the members agreed to a mechanism to prevent the rebuilding of inventories in consumer countries. This mechanism involves the continual adjustment of output.

It is described as follows in EIG's Energy Intelligence Briefing: "Buried in the furor over Iran's refusal to go along with the agreement supported by other OPEC members in Vienna is the informal adoption of a highly innovative price band mechanism that OPEC delegates hail as a breakthrough. Designed to keep the OPEC basket price in a range of $22-28/bbl, the arrangement calls for producers to hike output by 500,000 b/d on a pro-rata basis if prices remain above $28 for 20 days in a row and to cut output by a similar volume if prices fall below $22 for 20 days.

If this fails to move prices into the desired range, another 500,000 b/d production adjustment would be made 20 days later. OPEC delegates say that the mechanism will, for the first time, guarantee minimum national revenues, making budget-setting and fiscal planning less hazardous. In addition, it potentially provides markets with the stability that the producers and consumers-particularly in the US-have been demanding loudly for the past few months.15

In effect, then, the 10 members of OPEC agreed at the end of March to adjust production in unison to maintain prices within a $22-28 band. Those familiar with international economics will recognize this program as a "target zone system."16

There are two economic consequences of this decision. First, inventories will not increase because the price bands are inconsistent with price levels at which stocks increase.17 Second, the price bands ("target zones") turn the countries accepting the proposal into "swing producers." That is, these producers will jointly increase or decrease output as market conditions dictate.

OPEC's price stabilization scheme will affect the rate of inventory accumulation. Inventory levels of most commodities and the rate of inventory accumulation is governed by the spread between forward and cash prices. Positive spreads (contango) provide an incentive to build stocks. Negative spreads (backwardation) afford a reason to liquidate.

The floor set by OPEC seems to guarantee that the market will remain in backwardation and thus will discourage or prevent stock increases. This conclusion is based on the fact that the post-Persian Gulf war average price of crude is roughly $19/bbl (this is the mean to which prices revert).18 Markets generally tend to be in contango when cash prices are below the mean and in backwardation when prices are above it.

By setting the floor price at $22/bbl-which is $3-5 above the mean-OPEC has guaranteed that markets will remain in backwardation until its program is revised. As a result, inventory accumulation will be limited.

The new pricing system also offers Iraq the chance to marginalize the rest of OPEC. Iraq has seized the opportunity. Iraq has announced a production increase now, recognizing that the other OPEC members will cut output in response. The net effect will be to maintain tight markets while transferring income and possibly good will to Iraq.

At the same time, the other 10 OPEC members will be unable to counteract a decision by Iraq to cut production this fall because they lack sufficient capacity to meet the projected 30 million b/d requirement.

The world will be left with a gap of 1-2.5 million b/d between projected demand and world productive capacity absent Iraq if that country follows through on its promise to reduce output around Oct. 1. The cut will trigger a price escalation, just as the ones in 1979 did.

Inadequate non-OPEC investment

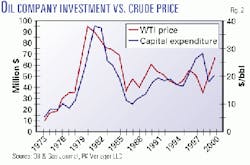

The pattern of low-level industry investment in 2000 is also very similar to the one observed during the first and second oil crises (Fig. 2).

A close relationship between oil prices and investment can be noted from 1973 to 1996. This relationship has been widely recognized in the industry and is traced to the propensity of companies to reinvest cash flow. However, the linkage broke down in 1997, when investment kept expanding as prices plunged. The breakdown continued in 1998. However, investment collapsed in 1999, as firms responded belatedly to the price collapse.

Preliminary figures for 2000 show that most firms do not plan to boost investment this year. Instead, most companies are proceeding cautiously. Balance sheets are being restored. Furthermore, companies are afraid that prices will collapse. An article in the Apr. 10 Business Week explained: "For one thing, after a recent round of consolidations, companies like ExxonMobil Corp. are focused on reining in costs and digesting the merger.

More important, most doubt oil prices will remain above $20 long term. Analysts say companies now make investments decisions based on $15-18/bbl.

Royal/Dutch Shell is even more conservative. Chairman Mark Moody-Stuart says he'll only do projects that will "fly at $14/bbl" and let them "sleep easy in their beds at $10."19

In addition, many companies have elected to repurchase shares, often finding that the lowest-cost reserves are found on Wall Street. BP Amoco PLC has announced plans to repurchase 10% of its shares at a possible cost of $30 billion. Shell has announced a plan to spend $5 billion repurchasing shares beginning in 2001. Other companies, such as Texaco Inc., are following suit.20

The effect of these transactions is to reduce the capacity of the world's oil industry to supply oil in 2000, 2001, and later, which effectively extends the potential crisis.

Producer behavior after price spike

The first and second oil shocks shared a third component: the willingness of individual producers to cut production as the crisis continued in order to sustain higher oil prices. Libya, Kuwait, and Venezuela each reduced output by more than 20% in 1974 to help maintain higher prices. Saudi Arabia and Iran followed suit in 1975.

A similar behavior was observed in the second oil crisis, as can be seen in Table 7. From this table, one can see that five countries other than Iran cut production in 1980, even as prices were doubling. Algeria, Kuwait, Nigeria, and Libya were most aggressive. Then in 1981, as prices approached $35/bbl, every member except Ecuador and Indonesia decreased output.

In almost every case, the decreases in production were made to boost prices. For example, as early as March 1979, several oil-exporting countries discussed cutting oil production.21 Nigeria announced a reduction in output at the end of July 1979.22 Kuwait did the same in November 1979 for the purpose of "preserving resources.23 Even Saudi Arabia cut back production.

The Saudi decision to rein in its output in 1980 was explained as follows: The Saudi decision to allow Aramco to produce above the government ceiling this year [1979], Prince Saud said, was intended to provide a "transition" for the consuming countries to curb demand. "This was as a sign of confidence on our part," he said. "We hoped this expansion of production would serve as a transition period for the consuming countries to act."24

Finally, as the oil prices began to fall from their peaks, some producers banded together to sustain higher prices. The Wall Street Journal reported the following:

The four African members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries-Libya, Nigeria, Algeria, and Gabon-held a secret meeting in Tripo* Sunday to shape a "common front of resistance" to pressures for oil price cuts, according to Libya's official news agency.25

A third crisis?

The conditions for a third oil crisis are in place. World petroleum consumption is increasing at better than a 2%/year rate, boosted by strong economic growth. OPEC will be operating at or near capacity by fall. One member of OPEC has indicated it intends to cut production in the fall if its demands are not met. Very small increases in non-OPEC production are expected.

If the past provides a guide, one can expect disorder to break out and prices to rise quickly once capacity is reached. Indeed, those with long memories may recall that it took Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani almost 2 full years to restore calm to oil markets after the collapse of Iran eliminated all of OPEC's surplus productive capacity.

Everyone involved with the oil industry should plan on a similar episode of chaos in the fall of 2000. The turmoil can be expected to last until 2002 or 2003 absent an economic slowdown (which would temper consumption growth) or the timely use of strategic stocks by consuming countries.

It must also be noted that the situation will remain tight for the next 2 or 3 years should the world be lucky enough to avoid its third oil crisis in 2000. As Matthew Simmons, president of Simmons & Co. International, has noted often, world productive capacity has remained static or even declined while consumption has been increasing. This trend continues even though costs of exploration and production are dropping rapidly.26

How high will prices rise? The answer is that no one knows. Prices rose fourfold during 1973 and 1975. Prices went up threefold during 1978-81. Such large increases are very unlikely today because prices have already risen by 120%-from $10 to $25/bbl. It is hard to imagine they could rise to or above $50/bbl over the next year given the increase from 1999. However, anything is possible.

Economic impacts

Twenty years ago, oil price shocks wreaked havoc on the world economy. Today, while oil remains important, a shock will have a much more modest impact because of the diminished role of oil in the economy.

The impacts of shocks in the 1970s were chronicled in detail at the Brookings Institution. As Edward Gramlich concluded, "Perhaps the most import result of this examination of supply shocks in the standard model is that whatever the macro response, shocks are very costly."27 Earlier, Fried and Schultze asserted that the 1973 oil price increase had been equivalent to a large tax increase, one that cost industrialized nations over 2 to 4% of their GDP.28

The recent increase in oil prices has triggered none of these concerns. A front-page article published in the Wall Street Journal on December 15 mused that no one seems concerned about the doubling of oil prices over the last year. Among the reasons offered for the absence of worry are that end users have hedged against higher oil prices and that suppliers are not pushing to raise prices in this more-efficient world.

Other economic forecasters seem to be equally unconcerned. Indeed, the only skeptic quoted is the author of this article, who commented that continued higher prices could be "a prescription for a fairly serious and sharp recession."29

Twenty years ago, oil price shocks wreaked havoc on the world economy. Today, while oil remains important, a shock will have a much more modest impact because of the diminished role of oil in the economy.

Macroeconomic Advisers LLC, one of the nation's leading economic forecasting firms, calculated that an increase in prices in 2000 that took crude to $40 by the fourth quarter would cut economic growth in 2000 from 3% to 2% on a fourth-quarter to fourth-quarter basis30: "The results, shown in a nearby table, suggest that if [The Petroleum Economics Monthly] is right, economic growth will slow all the way to 2.1% this year instead of the 3.0 shown in our baseline forecast.31

There seem to be six good reasons for the lack of anxiety. First, economists have become believers in the "New Economy." Second, oil represents a much smaller share of GDP in 2000 than it did in 1990, 1980, or 1973, the dates of prior price increases. Third, the economy is more open, which makes it harder for firms to pass on cost increases to customers.

Fourth, consumers can hedge against price increases. Fifth, natural gas has replaced oil as a critical input in the economy. Finally, most forecasters seem to rely on the forward price curve as an input to their models, an assumption that disguises the impact of price increases.

New Economy

In December, Financial Times carried a five-part series on the New Economy written by Gerard Baker.32 Baker begins by identifying the origins of the New Economy in the information age. Computer systems and data networks have made an enormous contribution to productivity growth, especially as they have penetrated more widely through the economy.

The New Economy has also benefited enormously from the introduction of new technology and the actions of venture capitalists, which have forced rapid change on older firms that might otherwise have resisted it. The increased flexibility of the labor market has also been an enormous benefit. Finally, Baker notes that the US has experienced low inflation recently, which has permitted the Federal Reserve Board to maintain a relatively benign monetary policy.

Harvard Economics Prof. Marty Feldstein, quoted in the Baker series, offers one of the clearest explanations for the economy's performance: "The main reason we have recessions is that the Fed tightens, and it tightens when inflation gets out of hand. But since that's the primary source of recessions in the US, the fact that inflation has been kept under control has made it possible for the Fed not to tighten and that has given us greater stability.33

Baker ends his series with a warning. He notes that, despite all the improvement that has contributed to the New Economy, the capacity of the economy to grow has not increased by more than 1 percetage point: "Long-term potential annual growth may have gone from the 2.5% of old to perhaps 3.5% today.

But only the most wildly optimistic would claim it was as high as the 4 to 4.5 now recorded. That means demand growth must slow over the next year or so-either through the much-sought-after "soft landing" of gradually slowing demand or something more drastic, such as a serious financial dislocation in stock or currency markets that might result in a nasty and painful recession."34

Decline of oil GDP share

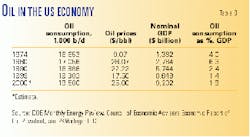

One of the factors that could bust the current economic bubble is the increase in oil prices. However, economists have correctly noted that the rise in oil prices today is much less important to the US economy than it has been in the past. The decline in importance of oil prices can be seen in Table 8, which shows the share of crude oil in nominal GDP.

From the table, one can observe that crude oil accounted for 4% of GDP at the time of the first oil shock, 6% at the time of the second oil shock, and more than 2% at time of the Persian Gulf War. In 1999, crude oil has accounted for only 1.4% of GDP, one quarter of the share 20 years earlier.

However, Table 8 contains a caution. The share of crude oil in nominal GDP will rise back to around 2% if prices remain above $25/bbl.

Table 8 also holds an implicit warning for economists. If prices reach $50/bbl, crude oil will have about the same share in the economy as in 1974. While no one projects such a rise, the calculation should remind readers that oil's influence on the economy has not necessarily been neutralized.

Greater economic flexibility

The increased flexibility of the economy is one reason most economists are not worried about the oil price increase. On this issue, they are correct. Over the last decade, every economy has become more adaptable in its use of every resource, including oil. Consequently, increases in oil prices trigger substitutions of natural gas or other energy sources in manufacturing.

The rise in costs in one location causes firms to transfer output quickly to other locations. Furthermore, over time, all manufacturing processes have become more efficient, reducing the importance of oil in output.

The improvement in economic efficiency can be seen in Table 8, which shows that the use of petroleum increased 16% from 1974 to 1999. During the same period, real GDP doubled. (The table shows nominal, not real GDP.) Over 25 years, the barrels per dollar of real GDP have declined by 40%.

This trend is observed in other countries as well. Increased technical change and greater flexibility have made most industrialized countries less susceptible to the effects of higher oil prices.

Increased hedging

In their Wall Street Journal article, Liesman and Schlesinger also noted that many firms are less exposed to changes in oil prices because they have hedged against the rise in oil prices.

The comment is true, although the use of hedging instruments is less widespread than the authors suggest. Furthermore, most hedges have a duration of 1 year or less. Thus, the impact of higher oil prices will be felt by the second quarter of 2000 if prices do not fall.

The short-term nature of hedging can be seen in the efforts of airlines to raise fares. Airlines are by far the largest users of oil-hedging instruments. Presumably these hedges would tend to discourage them from raising fares. However, the evidence is to the contrary. Since oil prices have started to rise, airlines have been aggressively boosting fares, explaining that their hedges gave them only limited protection.

Higher oil prices still matter

Despite the obvious benefits afforded by the New Economy, higher oil prices still are very important to the world economy. As Fried and Schultze noted 25 years ago, increases in the price of oil or any commodity have an effect analogous to a tax increase on a commodity-importing country.

Price declines have the opposite impact. Furthermore, as Republican presidential candidate Gov. George W. Bush has made clear, he and his economic advisers still believe tax cuts stimulate economic growth and tax increases cause economic losses.

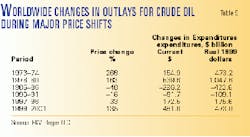

Table 9 has been prepared in an effort to compare several different disruptions: the 1973-74 price increase that occurred after the Arab embargo, the 1978-80 price increase that followed the fall of the Shah and the Iraqi invasion of Iran, the 1985-86 price collapse, the 1991-92 price decline following the Persian Gulf War, the 1997-98 price collapse, and the 1999-2000 price increase.

The increase in oil prices since March 1999 ranks second in absolute terms among the three disruptions that have occurred since 1973. The price increase following the Arab embargo raised consumer payments for oil by roughly $150 billion.

By contrast, the price boost imposed by OPEC in March 1999 will raise consumer expenditures by $480 billion. (The record was established during 1978-80, when consumer expenditures were increased by more than half a trillion dollars).

However, on a real basis, the current episode is the smallest of the three price increases. After adjustment for inflation, the dollar magnitude of the current raise is probably 20% smaller than the 1973-74 price increase and 70% smaller than the 1978-80 price rise. Since the size of the world economy is 50-100% larger today than in 1973 or 1980, the effects of the price increase can be expected to be much smaller, assuming that oil prices average $30/bbl in 2000.

The impact of the current episode also needs to be adjusted for the effect of economic growth. World economic activity has more than doubled since 1973 and has risen by at least 70% since 1980.

Thus, the current increase in prices should probably have no more than one-tenth the economic impact of the 1978-80 price increase and probably no more than one-quarter the effect of the 1973-74 price increase.35 This suggests that the effect of the increase in prices on world GDP should be measured in tenths of a percentage than in percentage points.

Roughly speaking, the data suggest that growth in world GDP will be reduced by 0.5% in 2000 if oil prices remain at their end-of-December levels. If, on the other hand, prices keep rising (for example, if OPEC maintains its production cut and empowers Saddam Hussein), the impact could be doubled to 1%. This does not mean the world will be thrust into a recession by the higher price of oil. Rather, it implies that world economic growth will be reduced from around 2.7% to 1.7% in 2000.

The moral of the analysis, then, is that oil prices matter to the world economy. However, the degree of importance has been moderated by the growth in the economy. Consequently, oil prices would need to triple from their current level to have the same effect on the world economy as they had at the time of the Arab embargo. Prices would have to rise by a factor of four or five from present levels to match the impact felt between 1978 and 1980.

Policy prescription

While energy undoubtedly plays a very diminished role in the world economy, the preceding section shows higher oil prices can clearly have a modest impact on economic growth if prices are allowed to rise unchecked. Twenty or 30 years ago, governments of consuming nations were powerless to stop the rise in prices. Today the situation is different, because these governments can take action.

Consuming countries own or control 1.2 billion bbl of crude oil and products. These volumes are stored in government and private facilities. The US government alone owns 568 million bbl of oil. Introducing some of this crude into the market would quickly moderate price volatility. Prices would have never reached $30 had the reserves been used last fall as proposed by Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY).

Proposals to use the reserves have received a very cold response from official sources and from energy security analysts. These opponents assert that the reserve was created to meet "shortages" rather than address market problems.

These views overlook a policy that, if implemented, could allow government officials to expand the size of the reserves at no cost to the taxpayer. The policy would involve the use of "swaps." Under a swap, firms taking oil from the reserve now would agree to return more oil in the future. For example, a buyer could agree to take 100 bbl in February 2000 and return 120 bbl in February 2001.

This strategy would have three immediate benefits. First, in the long run, strategic stocks would increase as the government took back 120 bbl for every 100 bbl released through swaps. Second, the expansion would be costless. Third, releasing oil would provide much needed liquidity to the market.

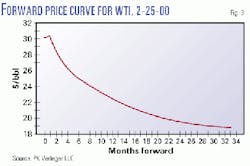

Many well-educated individuals may ask why any firm would be willing to take delivery of 100 bbl of oil now and agree to return 120 bbl later. The answer to this question lies in the forward price curve (Fig. 3). A buyer would take delivery of 100 bbl and promise to give back 120 bbl, if the economic value of the 100 bbl today exceeded today's cost of obtaining 120 bbl for delivery in 12 months.

On Feb. 25, 2000, the economics of the transaction worked as follows:

Value of 100 bbl in February 2000: $3,013.00

Cost of 120 bbl of oil to be delivered in February 2001: $2,731.20

Difference: $681.80

This calculation illustrates the effect of a steeply backwardated price curve. Under certain conditions, firms will trade a large volume of a commodity in the future for a small volume today. Most of the buyers presumably would hedge their positions, selling the oil quickly while buying futures to cover their future obligation. This action tends to depress the front of the price curve (causing lower spot prices), while lifting the back part.

No one has attempted to estimate the impact of an oil swap yet. However, comparing the ratio of cash oil prices to 12-month-forward prices indicates a close correlation between the "swap ratio" (the ratio of the cash price to the forward price) and the spot price of oil. This empirical relationship can be seen in Fig. 4.

A literal reading of this graph suggests that an exchange ratio of 1.1:1 would cap prices at around $23/bbl, while an exchange ratio of 1.2:1 would cap prices at $25/bbl. While it is wrong to accept such ratios at face value, they do imply that a swaps policy could stabilize markets. In other words, swapping strategic stocks seems to represent a good use of the taxpayer's oil when markets are excessively backwardated, as they are today.

This view will be challenged by some. One valid argument against this strategy is that it might provoke oil exporters into cutting production or at least not increasing output. This response is obviously possible. Such an action would boost the price of oil. However, it would not create the liquidity problems experienced recently in markets because continuing swaps would promote a better allocation of oil over time.

Current and future consumption would be depressed by larger amounts. Investment in new production would be increased, because forward prices are boosted by firms hedging their swap positions. Consequently, oil exporters would be marginalized more rapidly, and OPEC's ability to control the market would be reduced.

While this adjustment would take several years, it would ultimately squeeze producers from the market permanently. The prospects of such an outcome should deter OPEC from attempting any manipulation.

Others argue that such a policy attempts to pick a price for oil. This view is incorrect. Prices are determined by the amount of oil put into the market. OPEC has primary control over these volumes in the short run and thus has control over spot prices. Swaps only fix the slope of the price curve. By offering swaps, consuming nations would be using oil purchased by taxpayers to prevent markets from being excessively distorted.

Another objection to swaps is that they would anger the world's largest oil-exporting country, Saudi Arabia. This may happen. However, Saudi Arabia has enormous sums invested in the industrialized world. Excessively large price increases and disorderly markets threaten the value of these investments. Swaps moderate the disorderly markets and lend an element of stability to the market.

In summary, swaps represent an energy policy that should have been introduced several months ago. The doubling of heating oil prices during January and February and the impending doubling of gasoline prices could have been prevented had the policy been seriously examined last November.

Conclusions

The message here is quite simple: The world may be entering the third oil crisis in 30 years. Consumption is increasing rapidly. Crude oil productive capacity is being pushed to the limit. Private investment in exploration and production is increasing at a very modest rate. And Iraqi officials have recognized that they will have the opportunity to squeeze the market as early as October 2000. A crisis similar to the disruptions of 1973 and 1979-80 could be months away.

However, the crisis, should it occur, will have much more modest effects because the role of oil in the world economy has been decreased. The impact on GDP will be measured in tenths of percent rather than percentage points unless the price of oil rises above $50/bbl-a highly unlikely outcome.

Even this modest economic impact can be avoided. Governments of consuming countries have invested billions in strategic stocks. These governments can moderate the impact of the disruption by leasing their reserves using techniques developed by central banks. Ultimately leasing oil from strategic reserves will lead to the expansion of strategic stocks.

References

- Edward R. Fried and Charles L. Schultze, Higher Oil Prices and the World Economy: The Adjustment Problem (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1975), p. 29.

- Council of Economic Advisers, Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981), p. 183.

- States were (and are) permitted to limit the amount of oil or gas produced by private firms under federal statute. The "Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935" exempts this restraint-of-trade activity from federal antitrust activity. See Stephen L. McDonald, Petroleum Conservation in the US (Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 1971).

- Executive Office of the President, Cabinet Task Force on the Oil Import Question (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1970), p. 48.

- From 1973 until about 1986, OPEC members attempted to set price levels for crude along with output despite the suggestion from some quarters that such attempts could not succeed.

- "OPEC Cracks the Whip," Newsweek, Jan. 1, 1979, p. 14.

- Council of Economic Advisers, Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981), p. 183.

- International Energy Agency, Monthly Oil Market Report, May 2000, p. 4.

- US Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Short-Term Energy Outlook, February 2000, p. 54.

- US DOE, EIA, International Energy Outlook 2000, p. 175.

- A 1998 report by the National Petroleum Council, US Petroleum Product Supply-Inventory Dynamics, indicates that minimum operating levels have declined and that the concept may be impossible to measure.

- Energy Intelligence Group, Oil Market Intelligence, March 2000.

- IEA, MOMR, March 2000, pp. 17-19.

- "Queen Sacrifice, Checkmate?" Energy Compass, Mar. 31, 2000.

- OPEC Experiments with Market Micro-Management," Energy Intelligence Briefing, Mar. 29, 2000.

- Paul Krugman and Marcus Miller, "Why Have A Target Zone?" NBER Discussion Paper No.718, 1993.

- This publication has frequently commented on "supply-of-storage relationships." These relationships link inventory levels with the slope of the forward price curve (backwardation or contango). Empirical results presented on these pages suggest that the backwardation associated with a price band of $22-28 is consistent with the current level of stocks. Hence, it seems unlikely that there will be a significant change in stocks while the price band is in effect.

- The reported average is for WTI. The average price for dated Brent-perhaps a more meaningful number-is $17.60/bbl.

- "The Oil Patch Plays It Safe," Business Week, Apr. 10, 2000, p. 40.

- "Firms Look to Buybacks to Resuscitate Shares," Oil Daily, Feb. 24, 2000, p. 1; "Texaco to Resume Large Stock Buyback, Citing Cost, Concern on Capital Projects," Wall Street Journal, Mar. 21, 2000.

- "Several OPEC Nations May Restrict Output to Keep Supply Tight," Wall Street Journal, Mar. 26, 1979.

- "Nigeria Oil Cut Hinted," New York Times, July 26, 1979.

- "Kuwaitis Plan to Cut Oil Output," New York Times, November 28, 1979.

- "Saudi Arabia to Cut Current Oil Output 1 Million Barrels Daily after Year End," Wall Street Journal, Oct. 10, 1979.

- "African Oil Producers Meet to Discuss Ways to Resist Pressure for Price Cuts," Wall Street Journal, July 28, 1981.

- One of the extraordinary puzzles today relates to the decline in oil-finding costs, the decline in investment, and the decline in capacity. A year ago, The Economist noted the rapidly falling cost of exploration in its March 6, 1999, report "Drowning in Oil." The editors pointed out that costs were falling so rapidly that $5 crude might be just around the corner. Few reports have had poorer timing because the publication coincided with OPEC's March 1999 meeting. However, the report's pronouncement that costs are falling remains true. In light of this information, one must ask why investment and production are not increasing.

- Edward M. Gramlich, "Macro Policy Responses to Price Shocks," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Volume I (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1979), p. 166.

- Fried and Schultze, p. 21

- Steve Liesman and Jacob M. Schlesinger, "The Price of Oil Has Doubled; Why Is There No Recession?" Wall Street Journal, December 15, 1999, p. A1.

- Macroeconomic Advisers, Economic Outlook, Feb. 15, 2000, p. 18.

- Ibid.

- Gerard Baker, "The New US Economy," Financial Times, Dec. 13, 14, 16, 17, and 20, 1999.

- Baker, "Did a Brave Fed Kill Off Inflation, or Was It Luck? The New US Economy: Part 4," Financial Times, Dec. 17, 1999, p. 4.

- Baker, "Recession or Soft-Landing: How Will the Boom End? The New US Economy: Part 5," Financial Times, Dec. 20, 1999, p. 3.

- The impacts listed in this paragraph must be very qualitative because only rough measures of world GDP for 1999 are available. Furthermore, estimates for earlier years decline rapidly as one goes back in time.

The author-

Philip K. Verleger Jr. is a partner in the Brattle Group, Cambridge, Mass., and president of PKVerleger LLC, Newport Beach, Calif. He received his PhD in economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has written and consulted on petroleum economics for 30 years, serving at the President's Counsel of Economic Advisors, US Treasury, and at various academic and private sector institutions. Verleger publishes weekly and monthly reports on petroleum markets through PKVerleger LLC. This paper originally appeared in the January and February 2000 issues of Petroleum Economist Monthly. Further information is available at www.PKVerlegerLLC.com.