Oil price management: Why OPEC needs a real gulf crude market

Centre for Global Energy Studies

London

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries finally seems to have realized that it needs to find a more effective way to manage the oil market if it is to achieve its price objectives.

Over the past 4 years, oil prices have lurched from crisis to crisis in a boom-and-bust cycle that is a direct result of OPEC's failure to react promptly to clear market signals (see chart in preceding article, p. 90).

By waiting until prices fall below $10/bbl or surge above $30/bbl before adjusting output, OPEC has contributed to the volatility that it claims to abhor. Now, however, OPEC says it wants to vary supply more responsively so as to keep oil prices within a band of $22-28/bbl for the OPEC basket of crudes, thus creating the prospect of a more stable oil market in the future-if such an agreement can be made to work.

Price management

Price management is not an easy task, and history is replete with examples of commodity-price agreements and fixed-exchange-rate regimes that have failed to withstand market pressures.

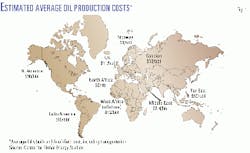

Nevertheless, OPEC seems to have no choice but to rise to the challenge, if it wishes to keep oil prices at levels well above the marginal cost of finding and developing new sources of supply, which lies within the range of $10-15/bbl for offshore oil fields outside the Middle East (Fig. 1). If the oil market operated according to the normal laws of supply and demand, oil prices would be determined largely by the much lower cost of producing oil from the giant oil fields of the Middle East, and there would be little development outside the region. OPEC's Persian Gulf producers, however, decided many years ago to restrict the area's output well below its resource-based potential in order to push oil prices higher and have therefore assumed the de facto role of marginal suppliers.

Given the disparity between the low cost of finding and developing oil in the Middle East and the much higher cost of doing so in the North Sea, Alaska, and the US Lower 48, there can be no doubt that OPEC has operated a successful price-fixing cartel. However, OPEC's deep-seated problem is that it only functions properly in a crisis. Oil prices have therefore fluctuated over a wide range as bureaucratic delays, internal disputes, and blatant cheating frequently undermine the effective operation of the cartel.

Only when oil prices threaten to collapse to very low levels or spiral upwards out of control does OPEC find the necessary unity that leads to decisive action. Successful market management requires much more responsive and timely intervention by the marginal supplier than OPEC has achieved to date. It also requires greater transparency about price objectives and the precise mechanism for market intervention than the organization seems willing to give.

Although OPEC has agreed recently on an automatic price adjustment mechanism that will add or subtract 500,000 b/d to supply if oil prices stray outside a range of $22-28/bbl for the OPEC basket of crudes for more than 20 operating days at a time, the details of the agreement have not been published officially.

OPEC's scheme for managing oil prices is certainly a significant step in the right direction, but it fails to address a fundamental problem that is likely to handicap any attempt to adjust supply in response to prices. Despite its self-appointed longer-term role as a price-fixing cartel, OPEC acts in the short-term as a price taker, selling its crude at formula prices determined by the market. Although the existing set of market structures based around New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) light sweet crude and International Petroleum Exchange Brent crude have evolved to provide an elaborate pricing mechanism for the many different grades of crude oil available to refiners, the market remains incomplete because it does not involve the direct participation of the marginal producers.

Instead of adjusting supply in response to prices, the big Gulf producers-who, after all, control the marginal source of supply-refuse to participate in an activity that they fear would weaken the control they exercise over their oil exports, selling instead all their output on terms that are generally unresponsive to prices. As a result, marginal supplies and prices are determined independently of each other, leaving the market without an essential safety valve though which crude supply can potentially adjust to changes in demand, making prices more volatile than they might otherwise be.

Unless OPEC is prepared to trade directly on the market, thus forming an explicit link between supply decisions and prices, it is difficult to see how the organization's new price regulation mechanism can work effectively. If OPEC really wishes to control oil prices, it needs to restructure the crude oil market around the world's marginal source of supply-the Persian Gulf.

An unrepresentative market

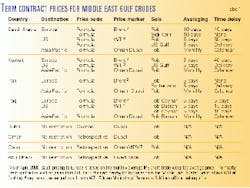

Persian Gulf producers supply around 15 million b/d of crude to the world oil market, most of which is sold directly to refiners under long-term contracts at market-related prices (Table 1).

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait operate the strictest policies, selling exclusively to long-term contract holders, enforcing destination restrictions, and refusing to allow the resale of their crude to third parties. No Saudi or Kuwaiti crude is therefore traded on the spot market. Iran also prefers to sell on term contracts and applies destination restrictions but does permit limited third-party trading for crude sold out of storage at Sidi Kerir in the Mediterranean, although this ceased as Iran's compliance with OPEC production quotas improved under the Riyadh and The Hague pacts.

Other gulf state-owned producers also avoid direct participation in the spot market, even though they do not enforce destination restrictions and use a uniform fob price all for their exports. Nevertheless, some Middle East crudes are traded, because the international oil industry has upstream equity interests in Dubai, Oman, Abu Dhabi, and Qatar, providing essential liquidity for the spot and forward markets that operate in the Middle East. Activity in these markets is limited, though, because equity crude is also sold on term contracts, the total volumes available are small, and all gulf crudes traded on the spot market, except Dubai, are priced relative to official government selling prices that are set retrospectively, which inhibits trading because prices cannot be fixed precisely in advance.

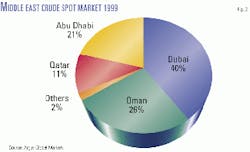

Last year, Petroleum Argus recorded around 500 spot and forward paper deals for Persian Gulf crudes, which is equivalent to just over 800,000 b/d of supply, or just 5% of the total volume of Persian Gulf exports. This compares with around 1,500 North Sea spot crude deals recorded in recent years, equivalent to 2 million b/d of supply, or about a third of the total volume produced.

The most liquid spot markets are for Dubai and Oman crudes, which together account for two-thirds of the Middle East deals reported by Petroleum Argus (Fig. 2). Although the UAE is a member of OPEC, all of Dubai's crude is produced and marketed directly by foreign companies with upstream equity interests and is typically sold either via spot market or by tender to Asia-Pacific refiners.

Dubai production is, however, now in rapid decline, threatening the future of Dubai crude as a reliable spot marker for Persian Gulf. Plans to stabilize Dubai output by reinjecting Iranian gas have had to be shelved because of US sanctions against Iran, and production has fallen from 410,000 b/d in 1991 to only 170,000 b/d this year-fewer than 11 cargoes/month and barely enough to support a liquid market.

Oman is not a member of OPEC, and foreign companies (mainly Royal Dutch/Shell) have direct access to around 400,000 b/d of Omani production through equity shareholdings in Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) and other companies, providing further liquidity for the small gulf spot crude market. Oman, though, is not an entirely independent marker, because spot cargoes are traded at a differential to the retrospectively set Oman official government selling price, which is, in turn, derived from Dubai. Nevertheless, spot price assessments for both Dubai and Oman are used as the reference marker for eastbound sales under term contracts.

There is also a forward and swaps market for Dubai crude that trades at a differential to Brent, providing a limited hedging mechanism for Middle East crudes. In the past, the forward market was more liquid than the swaps market, but declining physical volumes and problems with the forward contract have made swaps more attractive to hedgers.

Other commonly traded Persian Gulf crudes come from Qatar (Qatar Land, Qatar Marine, and Al Shaheen) and Abu Dhabi (Murban, Lower Zakum, and Umm Shaif).

Iraq remains a special case, because since sales contracts must first be approved by the United Nations as part of the UN oil-for-aid deal, and exports are priced differently for sales to Europe, the US, and the Asia-Pacific region; however, third-party trading is not prohibited, and there is a thriving spot market for Kirkuk from Ceyhan, on Turkey's Mediterranean coast, as well as occasional spot sales of Basrah Light from the gulf.

Without the participation of the major gulf producers, the Middle East spot crude market remains little more than a sideshow. It provides a useful but limited forum in which upstream equity producers, traders, and refiners can fine-tune their crude portfolios and-through the Dubai forward market-a link to the much more liquid Brent and WTI markets in the Atlantic Basin. The supply side, however, is concentrated in the hands of a few companies-mainly Shell, BP Amoco PLC, Conoco Inc., and TotalFinaElf SA-who have upstream equity interests in the region, and the underlying physical volumes available for trading on the spot market are too small to reflect the true impact of the huge volumes of oil that flow out of the Persian Gulf every day.

Inflexible supply

Most of the oil sold by Persian Gulf producers moves through channels that are very unresponsive to changes in price-either in absolute or relative terms.

Eastbound sales are linked by a pricing formula to the monthly average of published assessments for Dubai and Oman crudes for the month in which a cargo is lifted. Although Asia-Pacific buyers can hedge their purchases using the Dubai forward and swaps markets, most refiners in the East are still protected from absolute price risks by their domestic markets, which either permit them to pass through cost increases to consumers or guarantee them processing margins through price controls.

The main exception is Singapore, where refiners do need to hedge because they are fully exposed to the market; for the rest, the demand for hedging is likely to increase as price deregulation spreads through the Asia-Pacific region over the coming years. The Dubai swaps market is already used for hedging by some refiners in the East, and NYMEX is about to launch a new sour-crude futures contract settled against the monthly average of Oman and Dubai spot price assessments. This mimics the price index used by the gulf producers for eastbound term contracts, and NYMEX hopes that it will be widely used for hedging by Asia-Pacific refiners.

Although there is limited scope for arbitrage between East and West-especially for those crudes that are either sold on the spot market or are sold without destination restrictions using a single fob price marker concerns over long-term supply security, the use of destination restrictions and strict control over third-party trading for the majority of gulf supplies prevent Eastern refiners from responding quickly to shifts in relative prices. Most Persian Gulf crudes thus continue to flow to Eastern, long-term contract-holders whatever happens to absolute or relative prices.

Westbound markets tend to be more flexible, because Atlantic Basin refiners routinely modify their crude slates up to the very last minute in response to continuously changing crude and product prices. For this reason, westbound contract sales for Saudi, Kuwaiti, and Iraqi crudes from the Persian Gulf are linked by a pricing formula to Atlantic Basin market prices closer to the date of delivery than the date of lifting. In some cases, oil is also sold on a delivered basis from vessels owned or chartered by gulf producers.

This means that the seller-not the buyer-bears most of the absolute price risk while the crude is in transit from the gulf, making long-haul crudes from the gulf competitive with short-haul crudes in the Atlantic Basin. Consequently, the buyer is only concerned about the relative value of Middle East crudes as specified in advance by the term-contract formula and not the absolute price, because this will be determined by the WTI or Brent markets at or around the date of delivery.

Western refiners also face the same destination restrictions and strict controls over third-party trading as Eastern refiners for the majority of Persian Gulf exports, which prevent them from responding directly to shifts in relative prices, although it must be said that they are less concerned about long-term supply security and therefore more willing to cancel contracts if prices do not remain competitive. As a result, Persian Gulf crude supplies into Western markets are also relatively inflexible once contracts have been agreed, because the buyer must lift the long-haul crude without knowing what the price will be, but certain in the knowledge that it will be reasonably competitive with other short-haul crudes at around the date of delivery.

The use of destination restrictions and strict controls over third-party trading-combined with significant differences in the oil-related economic and competitive environment in the Atlantic Basin and Asia-Pacific markets, respectively-have allowed the gulf oil producers to discriminate very effectively between Eastern and Western markets, charging Eastern buyers a substantial price premium for security of supply.

For example, during January 1993-December 1999, Asia-Pacific refiners buying Saudi Light crude oil priced according to the Saudi term-contract formula paid, on average, about $1/bbl more than European or US buyers for the same grade of crude oil on an fob basis (Fig. 3). Similar premiums for eastbound sales can also be observed for other Saudi and Middle East crudes sold under destination-specific price formulas.

If the Persian Gulf crude market was allowed to operate freely, without any restrictions on destination and third-party trading, it would not be possible for the producers to discriminate between Eastern and Western buyers, and such a large premium could not be sustained over a long period. Instead, competition would iron out the differences between the prices paid by Eastern and Western buyers, establishing a single fob price for gulf crudes at the point of production, irrespective of destination.

Although there is limited arbitrage between East and West for those Middle East crudes that are not subject to destination or third-party trading restrictions or are sold spot by foreign equity producers, the volumes available to the market are small, and the current system creates significant barriers to trading that distort prices and inhibit the efficient allocation of resources, adding to price volatility.

Inefficient arbitrage

Oil supplies from the Persian Gulf should be playing a pivotal role in the world oil market.

On the one hand, they are the marginal sources of supply, for the gulf is the only area with significant amounts of unused upstream production capacity-most of which is in Saudi Arabia. On the other, the Persian Gulf straddles the crossroads between the established markets in the Atlantic Basin and the new, expanding markets in the Asia-Pacific region. Any owner of a cargo leaving the gulf has to decide whether it is going East or West, for a wrong decision could take months to unwind as crude arrives where it is not needed, backing local supplies out of the region, or being refined and reexported as finished products to markets on the other side of the world.

However, price discrimination and third-party trading restrictions imposed by Persian Gulf producers have created a marketing system that inhibits effective arbitrage between East and West. Although the oil market provides a clear signal in the form of the price differential between Brent and Dubai, the relative flows of oil from the gulf eastwards and westwards bear little relation to changes in the Brent-Dubai differential.

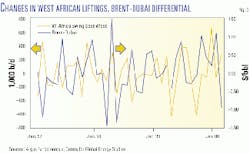

As Fig. 4 shows, the net swing in Persian Gulf liftings from East to West from January 1995 to the present is poorly correlated with changes in the price differential between Brent and Dubai. On average, the correlation between the East-West swing in liftings and changes in the price differential is negative, suggesting that an increase in the price of Brent relative to Dubai is associated with an increase in the volume of oil going east rather than west-which implies that the Brent-Dubai differential responds to changes in export volumes rather than the other way round. The relationship, however, is not statistically significant and close inspection of the relevant graph shows that the pattern is not consistent across the period. Sometimes there is a positive relationship, sometimes a negative relationship, and sometimes no relationship at all. This supports the idea that the current pricing system for gulf crudes inhibits effective arbitrage, because it appears that changes in Persian Gulf oil exports to the East and West are unresponsive to changes in the relative prices of Brent and Dubai.

Instead, the regional arbitrage mechanism works through West Africa, where Asia-Pacific refiners will buy more or less Brent-related crude depending on the size of the Brent-Dubai differential. West African crudes are very attractive to the less sophisticated Asia-Pacific refiners, for they have a high middle-distillate yield and a low sulfur content. Moreover, West African producers do not impose any destination or third-party trading restrictions on their exports. Sales to Asia-Pacific or Atlantic Basin refiners employ the same pricing formula based on the average of dated Brent quotations, typically 5 days after the date of the bill of lading. As Fig. 5 shows, more oil flows eastwards from West Africa when the Brent-Dubai differential narrows than when it widens.

Furthermore, the average correlation between swings in West African liftings from East to West and the Brent-Dubai price differential is positive rather than negative, indicating that changes in supply generally respond to changes in price rather than the other way round.

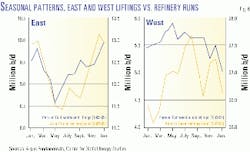

Closer inspection of the pattern of eastbound and westbound liftings from the Persian Gulf reveals that exports to the Asia-Pacific and Atlantic Basin markets have very different characteristics. Eastbound liftings from the Persian Gulf display a strong seasonal pattern and are closely related to the seasonal variation in refinery demand in the Asia-Pacific region (Fig. 7). Westbound liftings, however, display little seasonal variation and do not follow the seasonal pattern of refinery runs in the Atlantic Basin in the same way as eastbound liftings do.

These very different behavioral patterns of crude oil exports from the gulf suggest that the volume of oil going east or west is largely determined by the needs of Asia-Pacific refiners rather than relative prices in the two major regional markets. Although the overall volume of Gulf oil exports is also seasonal, because domestic consumption is higher in the summer in Middle East countries, the close match between the seasonal pattern of gulf exports to the East and Asia-Pacific refinery runs is too strong to be a coincidence.

As a result, exports to the West behave more like a residual item, with Atlantic basin refiners getting more gulf oil when Asia-Pacific needs less and vice-versa.

If this is the case, and gulf oil exports flow east or west without much regard for relative prices in the two major consuming regions, the Brent-Dubai differential is likely to be more volatile than if gulf exports were price-responsive. Although arbitrage will eventually bring prices back into line, this operates through changes in the volume of West African oil moving east, which require much bigger swings in price differentials, or counter-flows of refined products, which take longer to achieve. All this adds to the volatility of oil prices, because crude does not always flow to where it is most needed in the short term. In this way, relative crude shortages in, say, the Atlantic Basin can be perpetuated during the autumn and winter when Asia-Pacific refinery demand is at its strongest.

Although the Brent-Dubai differential will widen to reflect the shortage of prompt oil in the Atlantic Basin-as it did, for example, last winter-there is no supply mechanism to allow the strong price signal to do its work and redirect enough gulf oil from the East to the West to rebalance the market. As a result, the Brent-Dubai price differential continues to widen until West African exports out of the region are choked off or refined products start to flow back.

A more effective marker

The ultimate purpose of the oil market is to get the right oil to the right place at the right time.

In order to achieve this, supply and demand must respond to the signals given by the market, otherwise volatility will increase as prices continue to rise or fall indicating shortages or surpluses that are not being eliminated through changes in flows of supply and demand. The current system, in contrast, places the marginal source of global oil supply on the sidelines of the world oil market; the Persian Gulf keeps on pumping incremental barrels without regard to oil prices, sending cargoes east or west irrespective of need.

Although the gulf producers do eventually respond to prices by cutting volumes if prices go too low or by boosting output if prices go too high, there is no explicit mechanism that links supply to price at the point of production, because cargoes are sold at market-related prices that are determined after the oil has been lifted.

Market intervention by the gulf producers is therefore a purely political process, which is usually too slow and unresponsive to rapidly changing market conditions to provide an effective method of controlling prices.

If the Persian Gulf producers really want to set the price of oil, as they have indicated, they must stop acting as price takers and sell some of their output directly into the market at outright prices determined at the point at which the oil is lifted. Direct spot sales at the export terminal by the major gulf producers-especially Saudi Arabia-would have a number of advantages for the market as a whole. It would:

- Help create a more representative price marker that could also be used in the term contract sales of Persian Gulf crudes.

- Improve arbitrage between East and West by providing a universal fob marker price for all crudes irrespective of destination.

- Bring Persian Gulf producers into direct contact with the market by making them negotiate outright prices directly with buyers at the point of exportation instead of letting the market determine the price via a formula after a cargo has been lifted.

- Provide a much more effective method of controlling oil prices than the one proposed by OPEC.

Instead of waiting for oil prices to move outside a predetermined band, by which time the market has already acquired a momentum that can be difficult to halt, gulf producers could set a price at which they would be willing to sell (or buy) additional spot volumes. Like a central bank setting the discount rate, this would create a forward market around the preferred oil price that could be used by both buyers and sellers of Persian Gulf oil.

In this way, prices would not get too far above the preferred price level, because the market would know that the marginal producers would supply more oil; nor could prices get too far below it, because the market would know that the marginal producers would withhold supplies from the market if prices fell.

This sort of mechanism works perfectly well for central banks setting interest rates as long as the wider economic objectives are clear and the target interest rate is not unreasonable in relation to other trading partners' rates. The same would apply to oil. Setting an unreasonably high oil price would be self-defeating in the longer run, for it would encourage alternative supplies and discourage consumption, forcing the marginal suppliers to withhold more and more production in the same way Saudi Arabia was forced to cut output in defense of high prices in the early 1980s.

As with interest rates, the target oil price would also have to take into account the state of the world economy, and the producers would have to be flexible about the price they desired.

The key difference between a central-bank-type pricing mechanism for oil and the price band scheme proposed by OPEC is that the central bank is part of the market, supplying and withholding funds as necessary in defense of its published interest-rate objective. OPEC's price band mechanism operates at one remove from the market, releasing oil into the market without fixing an absolute price and waiting to see whether it is too much or too little-by which time it is more difficult to take corrective action. It also perpetuates an inefficient marketing system that discriminates between buyers in the East and West, making oil prices more volatile than they otherwise might have been and distorting the pricing signals that are necessary for effective market management.

Creating a truly representative market for Middle East crudes will require a radical shift in the attitudes of the gulf producers, which have remained resolutely opposed to spot and futures trading for many years. It is difficult, however, to see how OPEC can achieve its objective of limiting oil price volatility without making fundamental changes to the way in which its oil is sold.

Unless marginal oil supplies become more responsive to prices and the right market structure is created to ensure that the right oil does get to the right place at the right time, the oil market will continue to be extremely volatile, forever prey to the next crisis that will spur OPEC into belated action.