Trans-Korean gas pipeline could help Asia energy security, environmental problems

Since the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the world has been caught up in the great integrative trend for trade and business that is called globalization.

In Northeast Asia, relations among Japan, South Korea, China, and Russia have changed remarkably for the better, as can be illustrated by the progress of a number of oil and gas pipeline projects that have been proposed as cross-border, international energy projects.

However, it is still possible to find traces of the Cold War in the demilitarized zone along the 38th parallel of the Korean Peninsula and in the Taiwan Strait. In addition, there exist territorial disputes over islands between Japan and Russia and between Japan and South Korea. These may be among the bottlenecks in efforts to develop new economic and energy cooperation. Therefore, it is a priority to construct a new political and economical framework for mutual energy cooperation in Northeast Asia, overcoming the regional conflicts and searching for a new balance.

On the European continent, the development of an international natural gas pipeline network has progressed rapidly. One of the turning points was the "Ostpolitik" of the government of West Germany at the end of the 1960s, which helped enable the construction of a natural gas import pipeline from Western Siberia; this had been developed on the West Germans' own initiative in order to improve the relationship with the USSR under the Cold War constraints of the time. This is an example of the mutual interdependence of economic relations becoming strengthened by construction of the international pipeline, which in turn had a great influence on both countries' security and political systems.

This kind of movement can also be seen in Northeast Asia. For instance, in Japan, efforts toward economic cooperation with Russia are also spurring improvements in their relations in terms of foreign affairs and security. For this purpose, the idea of an international pipeline from Sakhalin Island or Eastern Siberia is expected to play a leading role.

In brief, an international natural gas pipeline will contribute to regional peace and stability in terms of strengthening the mutual economic dependence of each country.

Northeast Asia projects

Examining international natural gas pipeline projects in Northeast Asia, there are strong possibilities for the following projects to be completed within the next 10 years:

- Sakhalin Island pipelines to Japan (Niigata, Tokyo) and to China (Harbin, Shenyang).

- The Irkutsk pipeline from Koviktsinskoye, Russia, to northeastern China (Changchun, Shenyang) and Beijing.

- China transcontinental pipelines, from the gas fields of the Tarim basin in Xingjiang Uygur Autonomous Region to Shanghai.

Both the Irkutsk and the China transcontinental pipeline projects are being studied for possible extensions to Japan and South Korea in the near future (Fig. 1).

Change in N. Korea

Even after the demise of the Cold War, discussions regarding North Korea have emphasized the problem of security more than that of the economy, although there has also been some consideration of humanitarian aid in the way of food shipments.

Discussions between the US and North Korea, which had begun amid US concerns over suspected North Korea nuclear weapons development, resulted in the "Agreed Framework" in October 1994.1 Under this framework, from the viewpoint of nonproliferation, the US arranged to provide North Korea with two 1,000-Mw proliferation-resistant light-water nuclear reactors in exchange for North Korea freezing and ultimately dismantling its existing nuclear program. In addition, the US also was to provide North Korea with 0.5 million tonnes/year of heavy oil for heating and power generation until the first reactor is completed.

For the purpose of implementing these commitments, the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) was established in March 1995. However, after that, the political situation changed dramatically: North Korea developed long-range ballistic missiles, and a new president was elected in South Korea. Given these political changes, the US presented a review written by William J. Perry regarding its policies toward North Korea in October 1999, in which the US proposed a carrot-and-stick policy, the so-called "Two-Path Strategy."2

Nowadays, the situation of North Korea is gradually-but definitely-changing for the better due to the fact that North Korea has opened up (relatively speaking) a dialogue with the US and Japan and has also put out feelers to China and Russia.

Under these circumstances, it is not too far-fetched to consider involving North Korea in some aspect of a North Asian international gas pipeline network. If the international pipeline passes through North Korea, it will gain revenues from the the transit fee on the gas being shipped and will also gain needed energy supplies from any gas shipped on the line that is committed to many widely dispersed small and medium-sized power generation plants along the pipeline route. As a result, along with the power generation aspects of the KEDO project, it is likely that North Korea will be able to alleviate its persistent domestic power shortfalls very rationally and effectively.

Moreover, North Korea will eventually be able to replace the coal it burns for power with natural gas, which will contribute to efforts to reduce air pollution. The transit of an international pipeline through North Korea would probably expand the utilization of natural gas in the form of a so-called "free ride," due to its geographical location.

North Korean authorities have been stimulated by the progress of international natural gas pipeline projects in Northeast Asia. In 1998, under the leadership of North Korea's Asia Pacific Peace Committee, the government established the Natural Gas Research Society of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and appointed Kim Gyong Bong as its president, with the participation of governmental and research organizations. The society has started research on developing a policy of promoting natural gas utilization and the development of natural gas pipelines. Since 1998, the society has sent a delegation to annual international conferences, held under the auspices of the Northeast Asian Gas & Pipeline Forum, which is organized by nongovernmental organizations of six countries of Northeast Asia (China, Russia, Mongolia, Japan, South Korea, and North Korea) with activities that are related to natural gas. Through such conferences, the society has been rapidly collecting information and knowledge in the field of natural gas pipelines.3

Northeast Asian circular pipeline

Among the main four countries of Northeast Asia (Japan, South Korea, China, and Russia), areas that have great potential for growth in demand for energy are the Primorsky, Khabarovsk, Amur, and Sakhalin regions in Russia's Far East and the Northeast, Changjiang River delta, and the coastal Bohai Sea regions in China-to say nothing of Japan and South Korea.

Natural gas demand in these Northeast Asian regions will increase to as much as 205 billion cu m (bcm) in 2010 (Table 1). This volume is 2.6 times greater than that of 1995 and more than 90% of the natural gas demand of all of Northeast Asia.

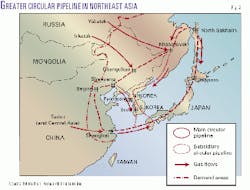

Looking at an international pipeline that would connect the regions of greatest gas demand, it follows that one could readily conceive of a "Great Circular Pipeline" in Northeast Asia (Fig. 2).

Then, the concept can be divided into two subset circular pipelines: the Circular Pipeline of the Sea of Japan and the Circular Pipeline of the East China Sea. The estimated gas throughput of these pipelines is 110 bcm/year and 95 bcm/year, respectively.

In 2010, natural gas is expected to still be delivered to Japan and South Korea mainly in the form of LNG, at a combined volume of 110 bcm, with the remaining 95 bcm supplied in the form of pipeline natural gas. These pipeline supplies will be transported from gas producing areas such as North Sakhalin, Yakutsk, Irkutsk, and the Western Siberian coast of the Arctic Ocean; the central Asian republics, such as Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan; and the Tarim basin gas fields of China.

Under this plan, the Korean peninsula takes on extreme importance and must thus offer assurances of peace and stability, more so than the other regions involved. Moreover, it is also required for Japan, South Korea, and North Korea to take part in the project, in addition to key roles beng played by China, Russia, and possibly the US.

Trans-Korea routes

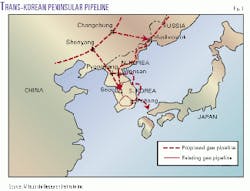

Regarding the Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline, we have two alternative routes, as an extension of the Sakhalin pipeline and as an extension of the Irkutsk pipeline (Fig. 3).

As for the Sakhalin pipeline, the route planned extends from North Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostock in Russia via Wonsan, Pyongyang, and Kaesong in North Korea and finally to Seoul. For the spur to Japan, the planned route entails a subsea pipeline from Wonsan that would land at one of two places on the west coast of South Korea (including Pohang) for compression and further shipment via subsea pipeline across the strait to western Japan.

As for the Irkutsk pipeline, there are two planned route alternatives. One would start at Chanchung, along the main Irkutsk pipeline, and from there extend via Jilin, Tyumen River area, and the Rajin-Sonbong Free Trade Zone to Wonsan and Seoul. The other would start at Shenyung on the main Irkutsk pipeline and extend via Shinuiju-Pyonyang-Kaesong to Seoul.

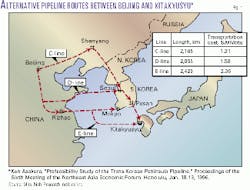

The Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline is recommended primarily for economic reasons. For example, according to the prefeasibility study of the pipeline between Beijing and Kita-Kyushu (Japan), the C-line extending across the Korean Peninsula-which mainly consists of onshore lines-is the most economic alternative (Fig. 4).

Trans-Korea line pluses

Regarding advantages of Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline development, there are three aspects to focus on.

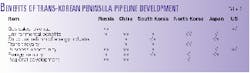

First, it would contribute to energy independence and further the establishment of alliances among the countries concerned. As shown in Table 2, each country, including the US, would receive significant benefits. Strengthening a framework of economic mutual dependence through natural gas trade would make a great contribution to building trust and peaceful relations in the region.

Second, it would offer environmental benefits. Switching from coal to natural gas would make a great contribution to air quality improvements in both northeastern China and North Korea and thus also help resolve the contentious issue of cross-border acid rain. As energy consumption is expected to increase in the future along with economic development of China, it becomes increasingly important to shift from coal to less-polluting fuels such as natural gas, in order to avoid a steadily worsening deterioration of the environment there.

Third, it would promote regional integration. The Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline could likely help instill an atmosphere amenable to the eventual unification of North and South Korea. And it also contributes to strengthening the foundation of a stable energy supply from the Tyumen River area to China, Russia, and North Korea. As a result, progress could be made on a regional development plan for the Tyumen River area.

It then follows that this project could afford opportunities to help make the greater concept of an "Asian energy community" come true.

Conclusions

Considering energy security, environmental issues, and economic growth in Northeast Asia in the 21st century, there is a real need for a project such as the Greater Circular Pipeline of Northeast Asia linking the natural gas demand areas of Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea.

With this project, the Korean Peninsula, on which the main discussion has been focused on security problems, would then begin to play an increasingly important role in solving energy supply problems related to natural gas. Moreover, the Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline would contribute to regional security and stability as a result of strengthening mutual economic relations in Northeast Asia.

The next step is for each country mentioned in this discussion, especially the two Koreas, to demonstrate support for the Greater Circular Pipeline of Northeast Asia and the Trans-Korean Peninsula Pipeline, taking into consideration the overarching concept of a greater Asian energy community.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Keun-Wook Paik, Research Fellow, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, UK, for his helpful comments and discussions.

References

- Agreed Framework between The United States of America and The Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Geneva, Oct. 21, 1994.

- Review of United States Policy Toward North Korea: Findings and Recommendations Unclassified Report, Dr. William J. Perry, Washington D.C, October 12, 1999.

- The author has been assisting activities of Natural Gas Research Society, DPR Korea from 1998 as a Secretary of the Northeast Asian Gas & Pipeline Forum.

The author-

Kengo Asakura is a research director and general manager at Mitsubishi Research Institute Inc., Tokyo, where he works in the national pipeline promotion department. He also has served since 1997 as secretary general of the Asian Pipeline Research Society of Japan and as deputy secretary general of the Northeast Asian Gas & Pipeline Forum. In addition, he served as secretary general of the National Pipeline Research Society of Japan during 1989-98. Other professional experience includes planning and research work on airport, harbor, and other civil construction projects in Japan and abroad, with specialization in energy economics, civil engineering, development planning and project evaluation, and remote sensing. Asakura has a PhD in engineering (project evaluation for energy development), an MS in civil engineering (remote sensing), and a BS in civil engineering (port and harbor engineering), all from the University of Tokyo.