Asian demand growth driving global gas trade outlook

Asia's booming natural gas demand growth will be the driver in international gas trade in the years to come.

That augurs well for the LNG and pipeline industries, as all forecasts point to continued strong growth in demand for natural gas in Asia.

However, while expansion of LNG trade will be an important component of that growth, LNG developers have overestimated the scope of growth in demand for LNG in Asia, which presages a shakeout in that business with long-lasting and major repercussions.

World gas market overview

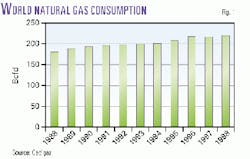

World natural gas consumption has grown at a moderate average rate of 2.0%/year during the past 10 years, nearly twice as fast as oil consumption.

In 1998, the world consumed 217 bcfd of natural gas, compared with 179 bcfd in 1988 (Fig. 1).

Despite faster demand growth, the development of the natural gas market has lagged the oil market. The share of traded natural gas in total consumption is far smaller than the share of oil. For example, in the US, it was not until the late 1950s and early 1960s that significant volumes of pipeline natural gas imports from Canada and Mexico began. Even today, while more than half of the world's oil is traded internationally in comparatively transparent physical and paper markets, over 80% of world gas production is consumed in the country where it is produced. In terms of the international gas trade, 75% takes place through pipelines, with the US and Western Europe as major consumers, and the remaining 25% is in the form of LNG.

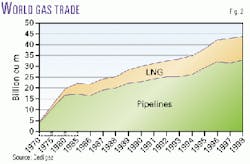

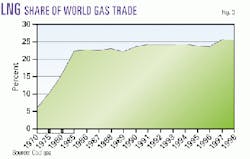

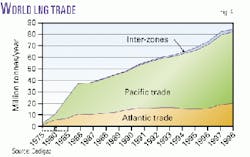

Starting from a small base of 4.4 bcfd in 1970, the international natural gas trade has grown rapidly and was estimated at 43 bcfd in 1998, or an annual growth rate of about 9%/year. Trade of LNG has been expanding even faster. In 1998, LNG trade reached 84 million tonnes/year (MMt/y), or 11 bcfd, up from 2 MMt/y, or 0.3 bcfd, in 1970; 23 MMt/y, or 3 bcfd, in 1980; and 53 MMt/y, or 7 bcfd, in 1990 (Fig. 2). As a result, the share of LNG in the total gas trade followed a consistent ascent, from 6% in 1970 to 16% in 1980, 24% in 1990, and 25% in 1998 (Fig. 3).

Asia accounts for about 75% of the world's LNG trade and constitutes one of the three main regional gas markets together with North America and Europe, including the former Soviet Union. Gas exports from the Middle East are expanding and will contribute to the growing LNG import demand in Asia and possibly in Europe as well. As shown in Fig. 4, while trade has been flat in the Atlantic market during the 1980s and 1990s, the growth of Pacific-based LNG trade has been steady and fast.

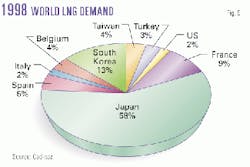

Japan is the leading LNG importer in the world, accounting for 58% of total LNG imports in 1998. A distant second is South Korea with 13%, and all other countries have shares of less than 10% and combine for 29% of global LNG demand (Fig. 5).

On the supply side, the leading LNG exporter is Indonesia with 32%, followed by Algeria 22%, Malaysia 17%, Australia 9%, Brunei 7%, Abu Dhabi 6%, and minuscule shares from all other countries, which together account for a combined 7% of total LNG exports in 1998 (Fig. 6).

Asian market in global context

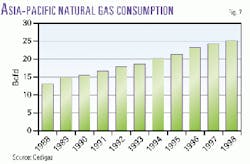

While world natural gas consumption increased by 2%/year during 1988-98, the average growth in gas consumption in the Asia-Pacific region was 7%. In 1998, the region consumed 25 bcfd of natural gas, up from 13 bcfd in 1988 (Fig. 7).

Despite increasing natural gas consumption in the region, it is still underutilized. The pattern of primary energy consumption in Asia, especially that of natural gas, is dramatically different from the world's picture. In global consumption patterns, oil accounts for 40% of total energy use, coal is a close second with 27%, and natural gas is third with 24%. Nuclear power and hydroelectricity compose a small component of the total.

The picture in Asia is altered if China and India are included. In this case, coal now accounts for the largest share with 44%; oil in percentage terms equals its global share, but natural gas consumption is only 10% of total energy use. Indeed, the region has the lowest dependency on natural gas when compared with every important geographical division in the world. The overwhelming influence of India and China as key energy consumers, especially coal, overshadows the regional pattern. If these two countries are excluded from the regional commercial energy consumption mix, the share of natural gas increases to 16%, which is still less than the global share. Without China and India, the share of oil also expands to 52%, which is larger than the global rate of utilization, while the share of coal shrinks to 20%.

The reason behind low gas demand in Asia can be explained by several factors. First, Asia lacks the gas-user culture that has existed in North America and Europe, where gas distribution infrastructure was first developed a long time ago in order to provide light and later heat. In contrast, Asia developed much of its centralized energy infrastructure later, when electricity distribution systems were used to meet most of its energy needs. Thus, it does not have the needed foundation from which modern gas use can grow more easily.

Second, because gas is more difficult to transport, developing gas use generally requires much larger investments than oil or coal. This has deterred lower-income countries in Latin America and Asia that are seeking rapid economic growth from pursuing natural gas projects; instead, they engage in the easier and smaller-investment projects that use oil. International corporations that explore oil and gas in Asia also prefer developing oil over gas because it provides faster returns on investments and is easier to market.

Third, the large investment requirements of natural gas explain in part why international gas markets are underdeveloped. In addition, gas resources in Asia are located far from the biggest and wealthiest centers of demand, which contributes to the slow development of a regional market. Without a gas market and a clear and transparent pricing of gas, consumption is constrained.

All these factors together contribute to low gas consumption levels in Asia. In addition, the promotion of gas use became a priority only after the economic boom in the 1980s, which resulted in skyrocketing energy needs in the 1990s. The slow moving and hesitant support of national governments in the region has not helped the cause of natural gas.

Despite these factors, the Asia-Pacific region represents one of the fastest-growing areas in the global natural gas industry. As mentioned earlier, the region's gas consumption grew three and a half times faster than the rate of world consumption during 1988-98. Gas trade in the region is predominantly in the form of LNG. In fact, Asia dominates the world LNG market. In comparison, Asian's transnational gas trade via pipeline is quite limited. There is a line from Malaysia to Singapore, another from a field off southern China to Hong Kong (which are now politically united), and a more recently completed pipeline from Myanmar to Thailand.

There are also several international projects in the region, which are either under construction or ready to proceed. These include pipelines from Indonesia to Singapore, Papua New Guinea to Australia, and Malaysia to Thailand in their Joint Development Area. Asia's individual gas pipeline projects will result in a slow and small increase in regional pipeline trade and could eventually create a regional pipeline network, at least within much of Southeast Asia. Plans for more-extensive gas grids will emerge only as each pipeline project becomes economical.

LNG outlook in Asia

While the LNG market dominates Asian gas trade, its market is relatively young and limited. Thus, each player and every change in supply and demand conditions has significant impacts on the development of the market and the future of natural gas. For example, there are only three Asian countries currently importing LNG: Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. It is no coincidence that these are the most advanced economies in the region or that all three lack indigenous fossil fuel resources. The Asian LNG market is the result of explicit government policy, as it has been elsewhere.

Except for the early 1980s, LNG imports in Asia have been growing at a rapid rate since Japan started the trade in 1969. LNG imports in Asia in 1970, with Japan as the only importer was less than 1 MMt/y (Fig. 8). It increased to 28 MMt/y in 1986 with the addition of South Korea. In 1990, Taiwan joined the ranks of buyers, and Asian LNG imports reached 39 MMt/y. In 1998, oil demand in the region declined because of the financial crisis, but LNG imports increased to 63 MMt/y from 62 MMt/y in 1997. For 1999, the imports increased to an estimated 69 MMt/y. In 2000, imports are expected to reach 72 MMt/y.

In Taiwan and South Korea, imports are handled by state-controlled monopolies. Both countries are in the process of deregulating LNG imports and privatizing these state monopolies. Nevertheless, the state-owned monopoly Kogas in South Korea was able to use its powerful position to invest heavily in a national gas transmission system, which facilitated the growth in demand for gas, especially in the industrial and residential sectors.

In Japan, a number of gas and electric utility companies dominate LNG imports. Historically, importers were responsive to policies promoted by Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry. This is slowly becoming a thing of the past with deregulation and an increasing emphasis on market-oriented business operations. The combined effects of multiple importers, exorbitant land costs, and legal right-of-way issues mean that Japan, which is the seventh biggest gas consumer in the world, has only a very limited gas transmission system. Thus, any plans for imports via pipeline will have to go directly to Tokyo or some other large demand center.

Asia still has large potential in increasing its LNG imports in the long-term. This is due primarily to the likely growth in LNG consumption in South Korea and India and, to a lesser extent, in Taiwan and in the emerging markets, such as China. While Japan is the leading LNG importer in Asia, the potential for future growth in that country over the next decade is limited.

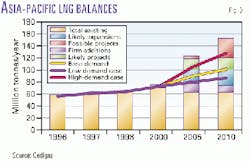

Estimates of LNG demand in the Asia-Pacific region 1997-98 and for the future are shown in the table. LNG consumption is estimated at around 90 MMt/y in 2000 and 100 MMt/y by 2010. South Korea and India will be the hubs of LNG demand growth in the region, while China has longer-term potential in the new century.

On the supply side, LNG exporters in the Asian region include Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and Brunei. Another 10-15% of LNG supply is imported from Alaska and the Middle East countries, including Abu Dhabi, Qatar, and soon Oman. The Middle East's share of the supply market is increasing. Indonesia and Malaysia, two of the world's largest suppliers, produce LNG through joint ventures involving participation from a state corporation and one or more of the largest multinational energy companies. Using the technical know-how of these multinationals, LNG-producing countries are able to capture a long-term foothold in consuming regions.

The impact of the Asian economic crisis on the LNG business in the region has been subtle. On one hand, the crisis did not cause a decline in demand, except for South Korea. On the other hand, the crisis forced suppliers to reassess the market and their plans for future build-up. Prior to the Asian financial crisis, the number of proposed LNG supply projects created the potential for oversupply in the region. If many or a majority of the potential projects came on stream, supply would have exceeded projected regional consumption even under the high-demand scenario (Fig. 9).

The reason behind the abundance of the proposed LNG projects relates to growing reserves, rising demand expectations, oil price behavior, and market strategies. Natural gas reserves in the Middle East have grown threefold since 1976 and account for 33% of proved global reserves. Although proved reserves in the Asia-Pacific region amount to only 6% of the world total, these reserves have doubled since the late 1970s. The discovery of several large gas fields in or near the region corresponded with rising LNG imports and strong economic growth and were therefore the target of potential projects.

In fact, LNG imports in Asia doubled during 1986-96, and a number of factors contributed to the optimistic demand outlook. For example, official LNG demand forecasts in South Korea were revised upwards several times in the mid-1990s and as recently as the spring of 1997. In addition, large oil companies have had increasing interest in the power market, so planned LNG facilities can constitute complementary or vertically integrated investments and potentially increase access to power supply projects. Finally, oil prices, to which LNG prices are linked, were high in the 1980s and relatively stable in real terms during the 1990s and thus contributed to the appeal of LNG projects.

The likely oversupply situation is changing the structure of the LNG industry. The power of buyers is increasing, and several importers have attempted to change the traditional terms in LNG contracts. South Korea has been leading the charge and is likely to be followed by other existing or emerging LNG importers, particularly India. The implications of this for the LNG business over the next 10-20 years can be enormous.

With plenty of LNG supply available, new buyers will be important in expanding the gas market in Asia. In addition to the pipeline plans mentioned previously, two countries may soon start importing LNG. China gave central government approval for LNG imports at the end of 1998. The proposal for a 3 MMt/y LNG project in Guangdong Province has also been approved, and importation is likely to begin in 2005. Other possible terminal sites are in Fujian and near Shanghai. International pipeline projects involving the Russian Far East or Turkmenistan, for example, will proceed more slowly and will not reach high growth in the southeastern coastal regions, where there is strong demand for power and a willingness to pay.

India is the third largest consumer of natural gas in the region and has been relying exclusively on domestic production. Gas accounts for only less than 10% of primary energy consumption, and the economy is becoming increasingly starved for natural gas and power. For a number of reasons, ranging from environmental concerns to competitiveness in power generation, natural gas remains a sought-after fuel in India. In the thirsty power sector, electricity generation based on imported naphtha and condensate will not be able to compete with natural gas, although increased domestic production could affect demand for gas imports. For now, gas imports via pipeline and increased domestic production remain more-distant possibilities. Meanwhile, both the government and private sector are pursuing LNG imports.

There are announced plans of somewhere between 10 and 20 LNG terminals in India. Many of these plans are still changing. Nonetheless, several leading projects are competing to be first in operation by 2002-03. Meanwhile, the steady stream of announcements regarding big LNG projects tends to obscure existing obstacles, e.g., the need to secure final gas consumers (many interested smaller power companies are not creditworthy), ensure sufficient prices, resolve shipping issues, etc., which may be sources of potential delay in meeting targets.

India as an LNG importer will differ significantly from existing buyers in the region, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Unlike them, India covers a wide geographical area, has a huge population that is likely to surpass China's over the next 2 decades, and has a much lower per capita income. It has some domestic oil and gas production and underexplored potential, as well as some existing pipeline infrastructure. Its large agricultural sector means that the fertilizer industry and petrochemicals in general will facilitate increasing use of natural gas in the domestic economy. While China could conceivably also benefit from a strong fertilizer industry, its pipeline infrastructure is less developed and what exists may not be as helpful as India's major pipeline in running inland from the coast with several spurs. Still, like much of Asia, neither China nor India has significant gas infrastructure for supplying residential or commercial users or even a wider variety of industrial users.

Conclusions

Since the 1970s, LNG has been a growing part of the international natural gas trade, which is dominated by pipelines. About 75% of LNG trade is in Asia. While the region has potential for future growth in both LNG and pipeline gas trade, many LNG suppliers had overestimated the demand potential in the region even before the Asian economic crisis began.

The overall proposed LNG capacity for grassroots plants and expansion of existing plants are excessive compared with the forecast growth in regional gas demand. The economic crisis has forced many exporters to rethink their supply plans.

The likely LNG oversupply is poised to change the structure of the industry and will possibly have lasting impacts on future LNG trade and implications for future LNG contracts in the region.

Still, the outlook for gas in Asia is extremely bright. Almost under any scenario, gas demand is expected to be the fastest growing segment of energy demand, bolstered by both energy needs and environmental considerations.

The author-

Fereidun Fesharaki is the president and founder of Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services (FACTS Inc.). Born in Iran, he received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran. He joined the East-West Center in 1979 and currently is a senior fellow and head of the Energy Project at the East-West Center. His area of specialization is oil and gas market analysis and the downstream petroleum sector, with special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region, Middle East, Latin America, and US. He is an advisor to numerous oil and gas and other energy companies, private and state-owned, and governments in the Middle East, Pacific Basin, Latin America, as well as the US government. Fesharaki is the author of more than 70 papers, has authored or edited 23 books and monographs, and serves on the editorial board of a number of scholarly journals devoted to energy resources and economics. Fesharaki was the 1993 president of the International Association for Energy Economics. In 1989, he was elected a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Since 1991, he has been a member of the advisory board of Mitsubishi Oil Co. He is also an advisory board member of the Far East Oil Price Index, based in Singapore. Fesharaki is also a member of the Pacific Council on International Policy. In 1995, he was elected as a senior fellow of the US Association for Energy Economics for distinguished service in the field of energy economics. In 1998, Fesharaki joined the board of directors of the American-Iranian Council.