Partnership turns around refinery in 2 years

With the unprecedented pace of change in Eastern Europe during the past decade, local refineries must improve their technical and financial performances to survive.

With these goals in mind, Industrija Nafte d.d. Zagreb (INA), Zagreb, Croatia's national oil company, has participated in a Profit Improvement Program (PIP) with independent refinery consultants of KBC since September 1997.

To date, the INA-KBC partnership has implemented profit improvement opportunities yielding benefits in excess of $47 million/year (equivalent to $1.20/bbl of crude).

A fundamental part of the program has been to review and upgrade INA's planning and scheduling systems and tools. Good planning and scheduling systems ensure that improvements made can then be sustained and reinforced by the ability to make better choices.

The PIP identified performance gaps and profit-improvement opportunities. The INA-KBC team also established a process for continuous profit improvement, changing the way INA did things at every level of the organization.

INA's support for the PIP and its determination to tackle the difficult issues of cultural change led to the creation of a more profit-focused and dynamic INA organization, better prepared for the challenges ahead.

1997 situation

With the elimination of trade barriers, Eastern Europe is moving from a demand-driven, state-owned economy to a market-driven economy with shareholder ownership.

Local refineries have had to adapt to the tough business environment familiar to their Western counterparts: fierce competition, low margins, strong regulatory pressures, and an ever-changing and increasingly demanding market.

These changes are forcing them to focus on bottom-line performance to survive.

For INA, the past decade has been even more turbulent as a result of the break up of Yugoslavia and the resulting wars. Export markets have replaced a large part of INA's traditional domestic market. It thus faces strong competition.

INA has two fuels refineries, one at Urinj (Rijeka) and the other at Sisak, and two lubes facilities, one close to Rijeka (Mlaka) and another close to Zagreb (Fig. 1).

In 1997, INA was suffering from significant losses in its downstream operations. A strategic review of the business showed that it was part of a vicious circle. High costs, both fixed and variable, were limiting its ability to compete in export markets. INA severely underutilized its upgrading units' capacities, which drove costs even higher.

The company embarked on a program of change and, in 1997, began to work with KBC, a refining and petrochemical consulting company. The initial objectives of the PIP were to improve refinery product yields and reduce high energy-consumption figures.

INA required quick and tangible results if the program was to succeed.

PIP Phase 1

The target for Phase 1 was achievement of a 50

- Benchmarking INA's fuels refinery operations.

- Identifying and evaluating profit improvement opportunities requiring no or minor investment.

- Implementing these opportunities quickly in the field.

The first step was for KBC PIP team members to understand INA's refinery business environment and operations, particularly the operating strategies and key constraints at the two refineries.

After site visits, the KBC team developed a virtual model of the two refineries using its refinery simulation technology, Petrofine. The team calibrated its proprietary process unit models based on test-run data, mechanical data, and site-visit discussions.

The model incorporated crude choice and product blending, reflecting the key constraints and refinery operating strategies of INA. It was tuned against an actual month of steady operation to match product yields, octane balance, hydrogen balance, and plant operating conditions.

During the initial site visits and the model-building phase, KBC developed a list of profit-improvement ideas.

It then prioritized the ideas and developed a hit list of 30 high-confidence opportunities at each site that required no investment or a minor one. These ideas were technically and economically evaluated in the refinery models.

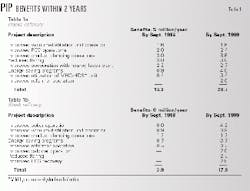

Evaluations of the hit list showed that if successfully implemented in full, the identified PIP opportunities would yield $22 million/year (93>/bbl) at the Rijeka refinery and $14.8 million/year (90>/bbl) at the Sisak Refinery. KBC and INA prepared an implementation plan for these projects.

Early results

In spring 1998, INA temporarily closed down its Sisak refinery. This shutdown forced the implementation program at this site to be postponed.

Meanwhile, at the Rijeka refinery, implementation of identified opportunities per the INA-KBC plan began in March 1998, 5 months into the project. The KBC implementation team moved to the site to work closely with INA team members. The team also included an operations superintendent who worked closely with INA at the unit-supervisor level.

The team continued to identify and analyze opportunities. In a successful project, identifying opportunities should become a permanent ongoing process.

The INA-KBC project team knew it had to demonstrate success early to gain project momentum and install belief and confidence in the refinery staff. By the end of September 1998, 1 year into the project, $13 million/year (54

In July 1998, the Sisak refinery restarted, and implementation of profit-improvement opportunities commenced immediately. Within a few months, PIP operational improvements led to a $4 million/year (27

After 1 year and with no capital investment, the INA-KBC PIP project resulted in implemented benefits of $17 million/

year. It was recognized, however, that if the benefits were to be sustained in the long term, the whole culture of INA needed to change.

During Phase 1, the INA-KBC management team identified a number of general organizational obstacles that the PIP team members-both from INA and KBC-had battled hard to overcome but were limiting the speed and extent of progress. These included:

- Strong departmental barriers inhibiting progress.

- Slow release of funds even for small, low cost and high return projects.

- Inadequate accountability for achieving measurable results.

- Badly structured and resourced planning organization.

INA employees, however, were feeling unsettled from recent reorganization and restructuring programs. Although further major organizational overhauls at that time were unwelcome, things needed to change for the company to survive.

INA asked KBC to supply senior management executives to each refinery to lead the change process within their organization. The executives were backed-up by on-site KBC refinery consultants and the operations superintendent.

The scope of the project was thus broadened to include improving business processes and tackling organizational and management issues as well as technical constraints.

Planning gap analysis

Since its early days with process optimization, KBC has recognized that the tangible benefits from making operational changes to refinery process units cannot be sustained in the long-term unless the refinery planning and scheduling systems are "fully on-board" with the profit focus.

For example, making the wrong crude oil choices immediately limits the potential for product-slate optimization. Further down the chain, the schedules should reflect what operation is best for that crude choice and so on down to the final product blend recipes. Even the finest advanced process control cannot make up for wrong planning and scheduling choices.

KBC used a planning "gap" analysis to compare the refineries' systems and tools with those of best practices. The analysis covered a 3-month look ahead of INA's supply chain from crude imports to product delivery at terminals.

A number of gaps were identified:

In general, there was too strong an emphasis on production rather than profit, with limited analysis of alternatives. Also, the supply planning process often was aimed at finding a feasible solution rather than an optimal one.

The time horizon was too limited to provide timely advice to crude and product traders, and the refinery planning and scheduling did not force the units to their limits. Communications were largely verbal and inefficient. Planning was reactive; the currently pressing problems always got priority.

A large part of the problem resulted from a lack of tools. The existing linear-program (LP) models were not sophisticated in structure nor in how they were used. In particular, rigorous feedstock optimization was lacking.

The scheduling software for crude-cargo arrivals and product-cargo exports was limited, and both the scheduling of units and the blending of finished products were undertaken at both sites without the use of any computer tools.

The planning gap analysis resulted in three main recommendations:

- Re-engineer the company's operational planning processes.

- Build a new LP for both refineries and the primary distribution system.

- Introduce scheduling and blending models.

The estimated financial benefits for implementing these recommendations were $8 million/year; a portion of this overlapped with the PIP benefits. The true benefits were much higher, however. Without good planning processes, the improvements made during the PIP will never be sustained.

The team made an immediate start by introducing a single-period blending model for fuel oils. These recommendations were accepted by INA and contracts were quickly established.

PIP Phase 2

For Phase 2, the KBC-INA management team continued initiatives from Phase 1 and built upon them by addressing management and organization issues.

Breaking targets into smaller components helped employees to see what could be achieved in their areas and encouraged ownership of the process.

New multidiscipline action teams were charged with removing organizational barriers and encouraging teamwork.

Employees set and achieved short-term goals; this process instilled confidence and enthusiasm. It was very important to ensure that the goals were realistic and tangible and the results measurable. For example, one goal was to blend 90% of fuel oil to inside a 5% target band within 3 months.

As more refinery staff came on-board with the PIP, in-depth discussions led to the generation of new opportunities.

KBC uses key performance indicators (KPIs) to track implementation during PIP projects. KPIs are process parameters that impact refinery profitability, such as fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) throughput or fuel oil blending give-away. These indices place the employees' focus on the profitability of the operations rather than just the operation itself.

During Phase 1, regular reviews of the KPIs were established. In Phase 2, the refineries increased the role and prominence of KPIs in daily refinery operations in several ways:

- Attaching clear objectives to KPIs.

- Attaching economics to KPIs to show employees how their actions affect the bottom line.

- Assigning each KPI to an individual to improve accountability.

- Carefully structuring the KPIs to the appropriate refinery level. For example, KPIs for operators and mechanics covered parameters (and money) under their control.

The team developed a spreadsheet-based tool to put together management reports, clearly summarizing the KPIs, the improved benefits and responsibilities, and the overall progress of the project.

The objectives and goals of the project were communicated throughout the organization, and achievements and success stories were publicly recognized.

Monthly, the KBC senior executives, INA's top management, and refinery managers met to discuss the progress and any constraints affecting bottom-line performance. These meetings encouraged high-level focus on "profitability constraints" lower in the organization. They also facilitated the quick release of funds for low cost and high-return opportunities.

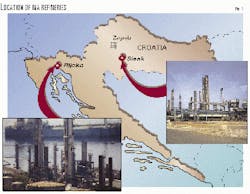

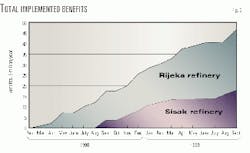

Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate examples of some of the tracking tools regularly discussed at these steering committee meetings. Fig. 2 shows the total benefits from both refineries. Fig. 3 summarizes projects and their benefits through September 1999.

After the early successes gained through the "quick hits," progress slowed while the Phase 2 initiatives took root within the organization of both refineries. After 6 months of Phase 2, it was evident that the old way of thinking was changing and a more profit-focused culture was emerging.

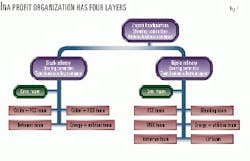

Improved results soon followed. By September 1999, total implemented benefits had grown to $47million/year-$29 million/year at the Rijeka refinery (equivalent to $1.20/bbl) and $18 million/year (also $1.20/bbl) at the Sisak refinery (Table1). In addition, a clear functioning profit improvement structure had evolved:

- A head office steering committee met to tackle organizational profitability constraints; it set goals and direction for the refineries and reviewed their progress.

- Refinery steering committees dealt with refinery profitability constraints; they set goals and direction for the action teams and reviewed their progress.

- Action teams reviewed unit constraints and set targets for the KPIs.

- Individuals monitored KPIs.

This structure (Fig. 4) is only four layers deep from the chief executive of INA to the unit supervisors and engineers. It cuts through many organizational layers and leads to a much more responsive and profit-focused organization.

New linear program

The project to build new refinery LP models for use in planning started in Phase 1. The corporate model includes the two refineries, ten product terminals, and 24 consumption areas.

Building, testing and installing the new LP models took about 7 months. For the next 4 months, the LP models were introduced and integrated with the new planning processes, which were being concurrently redefined.

For primarily cost reasons, INA asked KBC to build a custom refinery LP using standard software, rather than using one of the commercial packages. KBC developed a flexible system with a Microsoft Excel user interface.

The matrix generation used Visual Basic, and the LP solver used CPLEX, a mathematical programming software. The user needs to know only basic Excel functions to add feeds, products, and process units and to modify the reports.

KBC incorporated several best-practice features in the new LP models' structure and data:

- Crude assays with fractionated swing-cuts to accurately reflect the true quality of fractionation and allow cut point optimization.

- Base LP models for process units with data generated from calibrated nonlinear Petrofine process simulation models.

- Multiple feed pools for major conversion units (FCCs, coker, visbreaker) to allow optimization of sweet and sour operations.

- Product blending to quality specifications by mass or volume.

- Multirefinery capability, including the distribution system with transfers between locations.

The new LP models are planning tools that accurately reflect the yields, operations, and flexibility of the corporate refinery system.

New planning processes

The biggest change in planning processes was in the head office, where KBC helped INA establish a new organizational structure, which required new forms of interaction between head office and refinery planners. The new LP required training of staff and establishing more active links with traders and the sales department.

Before the new LP was finished, INA revised the content and format of planning documents. This helped to ensure a 3-month look ahead and better stock management. Traders began to explore the possibilities of exporting gasoline and LPG into Mediterranean markets.

Subsequently, as the LP was rolled out, new information flows were established and the staff adopted new responsibilities. KBC assisted in this restructuring, working with the head office and refinery staff in defining the new organization, the desired information flows, and job descriptions.

The refinery staff joined the head office LP staff each month in running the "global" LP and appraising the results. Communications increased, and new ideas were generated. The new planning practices have become the standard way of doing things.

PIP 3 Phase

The aim of Phase 3 is to move the responsibility for continuing profit improvement further into the hands of the INA managers and supervisors. Phase 3 began in September 1999 and will run for 12 months. The objectives for Phase 3 are for INA to:

- Take ownership of the tools and processes developed in Phase 2.

- Establish and execute monthly optimum LP plans and PIP targets.

- Establish responsibility and accountability for adhering to the plans and targets set.

- Close the gap between potential "best" operation and the actual operation.

KBC is still providing support at a lower level, namely:

- A senior management executive, based in the head office, assists where required by INA with any aspect of the downstream business.

- A senior consultant is available to both refineries to provide technical support and act as the link to KBC's pool of specialist knowledge.

- Planning specialists provide guidance on improving the planning process. They enhance the LP, assist in its use, and introduce scheduling tools.

Improved planning

In this latest phase of the planning support, the emphasis has changed. First, KBC sat with the supply planners in the head office and helped generate alternative plans. There were some formidable challenges:

What is the best way to dispose of a winter surplus of gasoline from the inland Sisak refinery? What is the best way to fill Rijeka's FCC unit, and which gasoline grades should it export? What is the best way to optimize refinery crude and atmospheric resid feed at Rijeka, bearing in mind requirements of an adjacent lubes facility and the local electricity generator?

The LP was the best tool for addressing these issues. KBC assisted INA staff in generating new vectors when unit performance changed.

As the LP usage increased, INA turned its attention to developing scheduling models. As pointed out in Phase 1, INA's capability was very limited. INA staff and KBC consultants together identified six areas where scheduling models would greatly assist the scheduler. Then KBC, INA schedulers, and the model builders jointly defined a scope for each model.

The team built Excel models that were simple, what-if models without any optimization. As the scheduling capability of INA's staff increases, it will buy or develop more sophisticated models.

Every organization needs daily, weekly, and monthly feedback processes to derive the "lessons learned" from the actual operations. Although INA's daily information flows contained comprehensive data, it lacked analysis.

Finally, on KBC's advice, INA started performing monthly lookback analyses, in which the LP was tuned to replicate actual operations for the previous month and used to generate an optimum at the previous month's prices.

Stepping between these two runs allows quantification of the effect of the various constraints. The process is time-consuming, but worth the effort.

The authors

Peter Bartlett is implementation services consultant at KBC. He has undertaken a variety of projects implementing refinery-wide benefits. Previously, he worked for Bechtel Ltd. as a process engineer on a number of grassroots refinery and oil and gas projects.

Bartlett holds a BSc in chemical engineering from the University of Manchester Institute of Science & Technology, UK.

Geoff Lee is a planning services senior consultant at KBC. He has undertaken a range of strategic and operational planning assignments worldwide, both with KBC and previously with Shell. Lee holds a D Phil. in physics from the University of Sussex, UK.

Zdravko Grgurac is INA assistant to the executive manager for downstream operations. He is responsible for the INA's refining and lubricant division. Previously, he was refinery manager at the INA Sisak refinery. Grgurac holds a BS in chemical engineering from the Zagreb University in Croatia.