Offshore NW Europe: A sector facing demise or just transition?

What is wrong with the oil and gas sector off Northwest Europe? Why is it ailing? Will it shortly lay claim to that title of the Gulf of Mexico of just a few short years ago: the Dead Sea?

This article will seek to address these questions and offer suggestions for solutions.

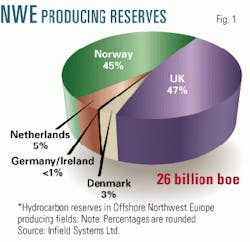

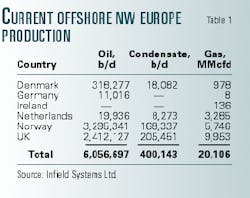

In the six countries engaged in oil and gas production on the North West Europe Continental Shelf (NWECS)-the UK, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, and Ireland-production levels have never been higher (Table 1).

And looking to the future:

- 37 new fields are currently under development.

- 49 new fields are currently being planned for development.

- 344 commercial finds have been made that could enter production in the next 20 years.

Surely something must be wrong here. Is it people's perceptions-like a stock market crash-or is there a fundamental factual basis to the current view of the industry that the North Sea is becoming (perhaps already is in the UK sector), a has-been, a safe but all too predictable elderly province of decreasing attractiveness, both to explorers and investors? The answer seems to be, as in most things in life, a little bit of both.

Yes, the big glittering prizes do seem to have already been won; but no, the game is not yet over by any means.

Although the European offshore industry has over 30 years of continual activity and development culminating in the current record levels of gas and oil production, many industry analysts and company executives appear resigned to its impending demise. There is no disguising the pain and reality that the current lack of large front-end projects is having on yards and contractors throughout the UK, Norway, and elsewhere in Europe, but the seeds of change and opportunity are still being sown.

UK and Norway

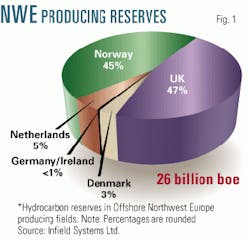

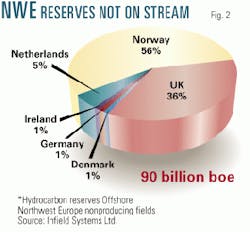

Figs. 1 and 2 show, by contrast, that although the number of potentially commercial field discoveries waiting to be put into production in the next 20 years (430) is almost identical to that of the 411 fields already brought into production, their combined reserves are but 22% of the total: 26 billion boe in prospect compared with 90 billion boe in production.

One thing immediately strikes the eye: the growing importance of Norway. This is due to two reasons.

First, Norway is, in the exploration-production cycle, about 10 years behind the UK and therefore has many major projects still in the development, planning, or consideration stages. Just as the UK brought into production Bruce, Brae East, Britannia, Scott, Nelson, Alba, Schiehallion, and Foinaven in the 1990s, we look to Norway to bring into production Grane, Kvitebjorn, Ringhorne-Forseti Balder satellites, Sogn (Fram-Gjoa), Kristin-Lavrans, Skarv-Idun and Ormen Lange in the 2000s.

Second, Norwegian frontier exploration, off central Norway, has turned up more and larger finds, leading to more intense competition amongst the majors for lucrative acreage and operatorships than has been the case of UK frontier exploration West of the Shetland Islands, where the scene, at the moment, is dominated by just one company, BP Amoco PLC.

Rest of NWECS

Until last year, Denmark was a sector of little exploration expectations, but then last summer, Nana-1 followed by Halfdan-2 and 3 brought to light a field that could ultimately yield more than 200 million boe.

Likewise in the Dutch, German, and Irish sectors recent finds and developments are taking place and lifting people's expectations once again.

This is a situation comparable to that currently pertaining in the US Gulf of Mexico, where finds of the order of Tanzanite (EI 346) and Hickory (GI 116) can be made in shallow waters, but giants of the order of Crazy Horse (MC 778) only in deep waters.

Deep waters

And it seems that only Norway in the NWECS area currently has licensed access to large new areas suitable for deepwater wildcatting.

As we stated in the World Deepwater Report, the resolution of the Faroes-UK maritime boundary may lead to a resurgence of activity to the southwest of the Norwegian sector.

But until that time, look to the drilling of only enough exploration wells west of the Shetlands to be counted on the fingers of one hand compared with two to three times this number off West Africa and Brazil and even more in the Gulf of Mexico.

It is this current lack of enthusiasm for further exploration drilling for the fields and developments of the future rather than a lack of success in the past that is making the North Sea and its adjacent areas seem a less and less attractive place to operate to the majors compared wiith West Africa, the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, and, increasingly, Brazil.

A radical change

The initial spur to oil and gas development off Europe throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s was the reaction to rising oil prices and governmental concerns over security of supply.

National oil companies with the necessary political will led the charge to create what is now the most developed offshore oil and gas infrastructure of any region in the world.

At first glance, the situation throughout the region today is much different, with privatization, regulation, and environmental concerns the key pressures resisting investment in deference to other regions of the world. The low oil price of 1998-99 clearly underscored the vulnerability of the region to the extent that exploration and investment throughout 2000 and early 2001 are likely to be at their lowest levels in over a decade. While it is cold comfort for contractors and laid-off engineers, the current difficulties within the region are acting as a positive stimulus to operators and governments to enforce radical change.

The UK government, having long seen the oil and gas industry as an income stream with disproportionate taxation, is starting to take a more proactive stance through regulation (e.g., License Information For Trading), taxation (roll-over relief) and cooperation (Oil & Gas Industry Task Force). Even the Norwegian government has accepted that current fiscal take levels-particularly the carbon dioxide tax and royalties-are too high and need to be reduced to ensure balanced field economics.

After the recent flurry of merger activity, the major operators within the region are all, almost without exception, reappraising developments and commitments within their European business units even though the current oil price has vastly improved profitability. BP Amoco's recent restructuring of its business units, which currently represent 30% of total offshore European liquids production and 10% of gas production (excluding ARCO), have clearly positioned them to either perform to still-higher levels or face sell-off. The recent sale by Repsol-YPF SA to Kerr-McGee Corp. of its entire European upstream operations has shown that this process will involve a number of operators leaving the region.

One major's options

As an example of the type of choices facing companies at present active on the NWECS, we can take a look at Royal Dutch/Shell's portfolio.

In the UK sector of the North Sea, Shell operates, in a partnership with ExxonMobil Corp. unit Esso, 41 fields containing 9.7 billion boe and producing a gross 500,000 b/d of liquids and up to 2 bcfd of gas. This equates to about 20% of total UK production. To do this, about 50 fixed platforms have been installed and 2 floating production, storage, and offloading facilities have been deployed. More are to follow. One hundred subsea completions are in use, and a further 50 may be needed to further develop 25 discoveries, holding about 1.3 billion boe that have yet to enter production.

In Norway, Norske Shell currently operates only one field, the 732 million boe Draugen field. Although having had to surrender the operatorship of Troll gas field to Statoil AS in 1995, Shell is looking to assume operatorship of the production phase of Ormen Lange field from the development operator, Norsk Hydro AS, when that 2.6 billion boe field comes on stream in 2006-07.

Elsewhere around the globe, while Shell does not appear to have struck it lucky on Block 16 off Angola, the same cannot be said of Bonga field, with 775 million boe on Block 212 off Nigeria. In the Gulf of Mexico, there are a series of major0 fields developed by tension-leg platforms, with a cluster of subsea satellites in the process of being tied back. In the Middle East, there is a major new redevelopment of the Nowruz and Soroush fields off Iran, and in Southeast Asia, there are major gas projects afoot off Sarawak and the Philippines. Finally, off northern Australia, a combined total of 3.15 billion boe has been found with 8 gas-condensate discoveries in the Evans Shoal-Greater Sunrise area in association with Woodside Petroleum Ltd.

In purely reserve terms, the choices for investment seem obvious. Either keep the North Sea ticking by small but judicious add-on satellite developments to try and get the maximum return for investments already made, or clean out the portfolio-keep the "silverware," but sell the other assets to raise capital for investing in more lucrative projects elsewhere.

Similar choices face all the other major North Sea operators. Thus asset divestments, called for by legislatures on mergers, may only anticipate those called for by economic factors by a matter of months. If the recent experience of the shallow-water Gulf of Mexico is anything to go by, and what the US does today Europe usually follows tomorrow, the majors will move out of the North Sea in search of pastures new and bigger projects. In the case of Shell, for instance, could this mean holding on to one or two key core areas such as Brent and, say, Shearwater or Gannet-Teal-Curlew and letting the others go?

Will small be beautiful?

This in itself produces a window of opportunity for smaller independent and niche companies to step in and take over to effectively run and get value from mature assets.

A good recent example of this is provided by the takeover of Unocal Corp.'s Heather field by Norwegian minnow DNO. Rather than shutting down last year, the field is now expected to have increased production and a possible field life of another 10 years or more, enabling an extra 80 million boe of additional reserves to be recovered. The downside of this situation is that, to do the job properly and in a cost-effective time scale, additional financial resources will be needed that a smaller company does not have at its ready command; hence, to do the job properly, DNO may have, in turn, to farm out up to 50% of the license to obtain enough dollars to realize the potential of Heather and its satellites.

The opportunities brought about by change are, and will be, capitalized upon by a growing number of smaller, leaner, "second-tier" operators. Companies such as Kerr-McGee, Lasmo PLC, Enterprise Oil PLC, and PanCanadian Petroleum Ltd., supported by a growing involvement in the upstream sector by former utility-turned-energy companies such as Ruhrgas AG and Gaz de France SA are profitably developing smaller prospects and managing field depletions.

Contractors: Operators?

The large regional contractors, such as Umoe, Petroleum Geo Services (PGS), and Aker Maritime AS, are increasingly becoming more akin to operators.

PGS, in its production-sharing arrangements, such as with Conoco Inc. on Banff and BP Amoco on Foinaven, has shown that operational proficiency and expertise is more than the preserve of the oil companies, although PGS is clear that equity participation is not an area it wants to move into more.

In a move that caused concerns over possible conflicts of interest between contractor and operator, the management of Aker Maritime has received initial qualification of competency from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate as a suitable field operator, although the firm is keen to stress that it would only look at projects that the majors had turned down.

The growing concentration by the majors on larger prospects will clearly leave many prospects within the scope of these smaller operators whether pure oil companies, contractors turned operator, or multidisciplined consortia brought together for each field development.

Gas to grow

While impending gas liberalization throughout Europe will not immediately require huge increases in offshore gas production-partly due to the current proliferation of long-term supply contracts and increased imports from North Africa and Eastern Europe-a changing political scene could benefit offshore operators.

A predicted increase in gas consumption over the next 5 years equal to an additional 35 billion cu m (bcm)-according to the European Union Energy Directorate's median-case forecast-is underscored by increased competition and growing EU concerns on supply security.

As European competition intensifies gas marketing, companies will become increasingly integrated upstream in an effort to ensure both security of supply and increased margins. These likely changes have seen a number of companies develop their asset portfolio with a greater weighting towards gas. TotalFinaElf SA not only has in place a fully integrated gas business from well (Elf Exploration & Elf Norge) to consumer (Agas) but is set to become the third largest (in terms of daily volume) offshore producing gas company in Europe and continues to seek alliances and partnerships in a variety of gas fields, as witnessed by the huge Elgin-Franklin development (48 bcm of reserves) and its recent Vale-Skrirne-Byggve development (12 bcm of reserves) with Norsk Hydro.

The European Commission, under the auspices of the Kyoto Protocol, is also putting increasing pressure on member states to reduce emissions of the greenhouse gases CO2, methane, and nitrogen oxides and the synthetic flourinated compounds sulfur hexafluoride, perfluoridized carbons, and hydroflourocarbons by a combined total of 8%. Most of the European hydrocarbon producers are net polluters, and this continued pressure would appear to be bad news, but the EC, in a rare admission of pragmatism, has highlighted the coal industry and its subsidies as its prime target area. A reduction in coal use, particularly in Germany, will further accelerate the growth of gas to the benefit of European producers.

New center of excellence

For its own part, the offshore industry is reacting to global competitive pressures with a sea change in management attitudes and the embracing of technology.

Initiatives that put increased control and responsibility at the bottom of the executive ladder are being rewarded with cost savings and improved working techniques that are adding years of productive life to mature assets. The threat of demise is a powerful motivator for crews and managers alike, but the levels of productivity and oil recovery ratios now being achieved throughout the region are quietly turning Europe into a center of excellence.

Thirty years ago, the European offshore industry was regarded as a pioneer in tough environmental conditions; now the region is a pioneer in tough economic and competitive conditions. The headline news of fabrication redundancies and empty large yards belies the changing nature of the European region. Fabricators of small platforms, such as Keith Yeaman Engineering, are experiencing unprecedented demand as will be subsea and deepwater specialists. The inherent undervaluation of the region and its prospects has been highlighted by the level of activity recently being shown towards the regional oil companies, service companies, and supply companies by the major European finance houses.

Offshore Europe has changed, with less low-tech fabrication but more high-tech development on an existing infrastructure. The headline-grabbing capital expenditure figures will decline relative to the 1990s, but if the oil price holds up, then-with the exception of the fabricators-the region could be ready to experience a miniboom.

Bibliography

The Prospects for Offshore Europe 2000-2004, Douglas-Westwood Ltd.

The World Deepwater Report 2000-2004, Douglas-Westwood Ltd.

The World Subsea Report 1999-2003, Douglas-Westwood Ltd.

The Authors

The views given are those of the authors. Roger Knight and Will Rowley are, with John Westwood, joint authors of the new regional study, The Prospects for Offshore Europe. Knight has spent the past 13 years being responsible for the collection, validation, and evaluation of the global offshore oil and gas data held on the Infield Database. He holds a PhD in geology from the University of London and is a member of the Institute of Petroleum.

Prior to the Islamic Revolution, Knight worked as a university lecturer in petrology and structural geology in Iran. His e-mail address is [email protected]. Rowley has a background in management with a number of large European organizations including the former Total SA. His work with Douglas-Westwood includes studies on both upstream and downstream business prospects in the oil and gas industries of a number of eastern European countries. He holds an Open Business School MBA and is a member of the Institute of Petroleum. His email address is [email protected]