US interstate natural gas pipelines begin to cope with firm-capacity turnback dilemma

Even as the number of US interstate natural gas pipeline companies continues to dwindle through mergers and acquisitions, the survivors must grapple with what is arguably the most critical issue they face: capacity turnback.

Capacity turnback is the reduction or return of capacity to the pipeline company at the expiration of a firm-transportation contract. Firm contracts-typically carrying tariffs higher than those for interruptible service-ensure the right to transport gas through a pipeline without disruption. Any contracts for unwanted capacity, in turn, must be remarketed to other prospective shippers or risk undermining the pipeline system's profitability.

The issue of capacity turnback is one that some pipelines have been dealing with for a few years, while others are still anticipating its arrival. And in light of a rapidly maturing gas industry in the US-especially since the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's passage of Order 636, which unbundled transportation and storage services-pipeline companies are coming up with tailored approaches to coping with their own capacity turnback dilemmas.

EIA analysis

Judging from an analysis the US Energy Information Administration provided OGJ that includes data through October 1999 (an updated analysis will be posted soon on EIA's web site at www.eia.doe.gov), it is apparent capacity turnback is an issue that looms over a number of US interstate pipeline systems, especially in the US Midwest, Northeast, and West (Fig. 1).

EIA estimates that about 18 trillion btu/day of firm transportation capacity will be turned back to pipeline companies as shippers' contracts expire over the next few decades. Basing its estimate on data from 64 pipelines, EIA reckons that the capacity that will be turned back represents nearly 20% of the total 97 trillion btu/day of firm capacity held on July 1, 1999.

Remarketing the capacity then becomes the main challenge that pipe- lines face. "Some portion of the capacity that is turned back to pipeline companies will likely be picked up by other customers," said EIA, "depending on future growth in demand for natural gas, infrastructure growth, location, and price for the capacity, and other market changes."

However, even if all of this capacity were to be remarketed successfully, EIA said, pipelines could still experience some revenue loss due to the need to offer discounts on remarketed capacity. "This potential lost revenue could become a concern to both the pipelines and to remaining holders of transportation contracts, whose rates might go up," said EIA.

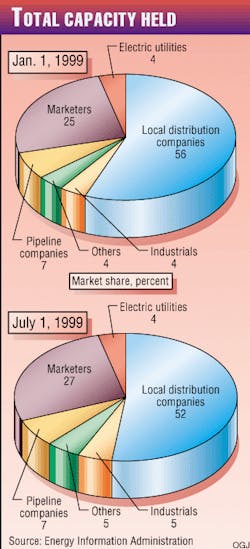

In addition, there has been a shift in market players in the last few years, as EIA notes a change in those holding firm-transportation contracts: "In recent years, an increasing percentage of the gas moving through local distribution systems is owned by companies other than the local distribution companies (LDCs), who held about 50% of the firm-transportation contracts on July 1, 1999 (Fig. 2). As a result, the LDCs' need for firm transportation has decreased."

Natural gas marketers, on the other hand, have steadily strengthened their presence in the pipeline capacity market, increasing their share of firm-transportation capacity to 27% in mid-1999 from 24% in 1998.

Capacity holders

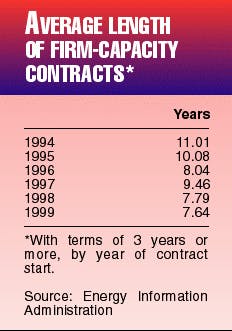

Overall, shippers that sign up for firm-transportation capacity for longer terms-contracts exceeding 3-year terms-are holding the capacity for shorter periods of time, EIA notes (see table). The average contract period for these longer-term firm-capacity contracts declined to about 71/2 years in 1999 from about 11 years in 1994. This trend changed only when the longer-term contracts-starting in 1997-increased to an average length of about 91/2 years from about 8 years for those starting in 1996, said EIA.

Another trend, notes Barbara Mariner-Volpe, senior analyst at EIA, is that the volume of capacity under firm-transportation contracts has risen by 2 trillion btu/day from Oct. 1, 1998, to Oct. 1, 1999. This increase in firm-transportation contracts, however, has not been able to keep pace with physical capacity expansions, which have amounted to more than 2.4 trillion btu/day during the same period.

This increase in contracted capacity is almost entirely associated with pipeline systems serving the US Midwest, said EIA. In fact, about 1.1 trillion btu/day of capacity, or over 50% of the total increase, is held by two shippers on one particular pipeline serving the Midwest. One of these two shippers holds 0.3 trillion btu/day of capacity under a short-term contract with an extended end-date; the remainining 0.8 trillion btu/day of capacity is associated with no-notice service and enhanced-transportation service contracts that have seasonal capacity levels that range from 0.8 trillion btu/day during the heating season to almost 0.5 trillion btu/day other times of the year.

Retail restructuring and open access in some states have also played a part in the increase in contracted firm transportation, Mariner-Volpe said. In some cases, third-party marketers are building their own transportation capacity portfolios in lieu of taking over capacity held by LDCs. As a result, LDCs have no other choice but to retain that capacity until the contract under which it is held ends, at which time the LDC will likely turn its capacity back to the pipeline company, she said.

In other cases, third-party marketers can take over the interstate-transportation capacity contracts used by the LDC in order to deliver gas to former customers of the LDC. If this occurs, the contract terms and capacity levels are transferred directly to the marketers, and no net reduction in capacity takes place, said EIA.

El Paso Natural Gas

El Paso Energy Corp. unit El Paso Natural Gas (EPNG) has been dealing with capacity turnback for perhaps longer than any other interstate system. "We're kind of veterans at this business," said Al Clark, vice-president, marketing and operations control, for EPNG. "Our first significant turnback capacity occurred back in 1992 when Southern California Gas Co. had the right to step their contract down from 1.75 bcfd to 1.45 bcfd," Clark said. The 300 MMcfd was subsequently remarketed to other shippers under new contracts.

Another series of step-downs, which occurred during 1996, led to almost 400 MMcfd of capacity being turned back to the pipeline company. EPNG chose to put in place provisions to deal with the stepped-down contracts in its rate-case filing at the time, explained Clark.

The filing included an agreement with its customers to split the risk for a 10-year period, from Jan. 1, 1996, through Dec. 31, 2003. EPNG's shippers agreed to pay 35% of the cost of the capacity as if it were not recontracted, and EPNG agreed to be responsible for 65% of the costs.

"[Our shippers] didn't want to have the uncertainty of unsubscribed capacity on the system, and we didn't want the uncertainty. And this is the way we brought some certainty to our business so that we could go on and conduct business," Clark said.

Starting on Sept. 1, 1999, EPNG posted on its electronic bulletin board a parcel of 1.2 bcfd of firm transportation service that had been held by Dynegy Inc., subject to its right of first refusal. The parcel was first purchased by Enron North America Corp. (OGJ, Jan. 3, 2000, p. 31). Due to certain regulatory complications, however, Enron was released from its agreement, and the capacity was purchased by El Paso Energy unit El Paso Merchant Energy Co. for $38.5 million.

Overall, Clark said, there are five basic reasons that EPNG is bullish on demand for natural gas transportation capacity to California and on the outlook for transportation capacity de- mand in general:

- The California market is growing at about a rate of 2%/year, moving toward elimination of a capacity overhang.

- There is tremendous growth in natural gas requirements in the northern tier of Mexico, and EPNG parallels the US-Mexican border from El Paso to California. EPNG says it is suited to provide gas transportation services to power plants and the other industrial, commercial, and residential markets being developed in the northern tier of Mexico.

- There has been a tremendous amount of gas and electricity "convergence" in the US in general and in California in particular.

- There has been a proliferation of proposed independent merchant pow- er plants that are going to sell into the power grid going to California and to the other areas in the western US.

- There is an emerging shift in the nationwide flow of gas supplies because of new pipeline projects being built out of Western Canada into the US Midwest, such as the Alliance Pipeline project and the other recent expansions.

Texas Eastern

It was in 1998 when Texas Eastern Transmission Co. (TETCO), owned by Duke Energy Corp., Charlotte, NC, first experienced the problem of turnback capacity, says Greg Rizzo, vice-president of regulatory affairs, system planning, and pricing. "We've actually been very forthcoming with the capacity turnback on our system, going back for about 3 years, maybe even longer than that," Rizzo said. Through this awareness, TETCO has been able to actively and creatively manage its way through the developing problem over the last few years.

One of TETCO's most significant programs to cope with its capacity turnback dilemma has been its Customer Rate Initiative (CRI).

TETCO had concerns early on about the potential for capacity turnback on its system, due to uncertainties about unbundling at the state level and the fact that the company was seeing its system being used more efficiently by customers directly controlling storage and capacity release, Rizzo explained.

Under its CRI, TETCO designed a program that would result in long-haul rates being decreased starting Dec. 1, 1999, by about 17%, Rizzo said. "Just from a frame of reference, our long-haul rate, not including fuel cost, from the Gulf Coast to Market 3, the New York-New Jersey area, right now isellipse58¢[/Mcf], and it will decrease to about 48¢[/Mcf], so [that is] about a 10¢ decrease, about a 17% reduction," he said.

Rizzo explains that, when Order 636 was implemented, TETCO, like many other pipelines, incurred certain gas-supply realignment (GSR) costs. TETCO's rate is roughly 7.5¢. Under the CRI program, TET-CO has agreed to lower its depreciation rate. By doing so, said Rizzo, the company can take the funds and use them to pay its GSR costs. By doing this, TETCO's 7.5¢ component will come out of rates about 2 or 3 years earlier than planned. "In addition to that," said Rizzo, "we'll further lower our rates so that, overall, once that's paid off, we'll have about a 10¢ rate reduction."

In general, Rizzo says that the market is experiencing a "period of confusion" with regard to capacity turnback that breaks down in three areas:

- LDC unbundling. As a result of the state unbundling that LDCs are facing, there is uncertainty about what role they should play in holding long-term contracts to serve their market areas. As a result, LDCs are beginning to turn back some of that capacity to the pipelines.

- Marketer confusion. Marketers, which are the next logical holders of this capacity, are not prepared to step up to take long-term firm capacity the way the LDCs previously contracted it.

- The success of Order 636. The market has gradually gotten better at utilizing storage service along with other transportation services after the launch of Order 636. The capacity-release market and other segmenting services also are being used more effectively.

CNG Transmission

The major transportation contracts on CNG Transmission Corp., Clarksburg, W.Va., will not begin to expire until 2001-02, says Georgia Carter, vice-president, wholesale services, regulative businesses. "In these first rounds coming up," Carter said, "the contracts that are coming due [are] mainlyellipse about 60% storage contracts."

CNG is operator of one of the largest underground natural gas storage systems in the world. "These facilities have been around for a while and have depreciated," Carter explained. "It's also a pretty flexible service, so, with the contracts that are coming dueellipse we're pretty comfortable with that storage part, we're very competitive, and we [think that we] can remarket [the capacity].

In addition, Carter says, CNG is typically fully subscribed for its winter services, which are primarily for storage. "We are a pipeline located up in the Northeast, delivering major quantitiesellipseto a lot of the major LDCs. Most of these LDCs probably do rely on our services, so we have a pretty good level of comfort about being able to remarket the wintertime portion of the contracts coming due," she said. It is for this reason, Carter explains, that CNG views its summertime capacity most at risk with regard to remarketing capabilities.

"All of the activity that goes on in the summertime is storage refill," she said. Recognizing that unbundling is occurring at the LDC level, CNG is looking at ways to help facilitate the process. "One of the things that we're doing is [that] we're changing some of our existing services, adding options that are intended to make it more attractive to marketers who may be providing a retail service and make it easier for the LDCs to unbundle and still maintain reliability," Carter said.

"It's nice to be a market-area pipeline with a bunch of storage," she said, "because we [can] provide a lot of swinging and peaking-types of servicesellipseWhat we have to look at is [that] the way we've sold [capacity] in the past may change. And we need to look at ways to sell it in the future. How do you repackage your assets?"

With all of its storage capacity, and given that CNG can handle swinging on its system, it also is trying harder to attract power generation loads to its customer base, Carter said. This would be another way to market its summertime capacity.

"Most of these power generation customers we expect would be moving gas around under interruptible contracts. We really don't expect to see exactly the same type of contracting on our system-although by no means do we think we're going to lose all of our summertime load, either, because we still have demand on the system," Carter said. Carter speculates that partnerships with other pipelines also will play a critical role in successfully remarketing turnback capacity and using efficiently the existing infrastructure in the Northeast.

Although the Atlantic Alliance gas pipeline project-involving the delivery of gas to the US Northeast from the Chicago hub and the Niagara import area-is technically not a partnership, CNG is involved in the project with El Paso Energy Corp.'s Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. (OGJ, July 26, 1999, p. 46). "There are multiple interconnects between our two pipelines andellipseby working cooperatively, we can move quite a bit of gas with some relatively minor facility additions," Carter said.

In general, Carter said, "[Capacity turnback] is certainly a concern for the pipeline industry, because we're a pretty capital-intensive industry and we have certain revenue requirements. As you see more and more contracts expire and pipelines starting to remarket, the market is still there, and [it] is actually growing. So, I'd have to say, in balance, that we're optimistic. We think that there is opportunity as well as risk."