Greece's Caspian export alternative bypasses Bosporus Straits

Greece has entered the Caspian Sea export pipeline debate in full force, promoting its own alternative route for bringing Caspian Sea crude to market.

A number of Caspian oil projects involving main export pipelines and secondary pipelines have arisen in recent years, sparking frequent and fierce debate about each one's economic and technical feasibility and political viability (OGJ, Apr. 19, 1999, p. 29).

Greece's proposal was unveiled with little fanfare more than 4 years ago and has not received the kind of attention some of the more politically embattled pipeline route options have-perhaps largely because it was initially conceived as an option for exporting Russian oil, whereas the Caspian export projects have focused mainly on new crude oil production in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

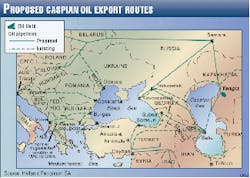

Greece's Foreign Minister Karolos Papoulyas confirmed the signing of an oil import pipeline agreement among Russia, Bulgaria, and Greece in late 1995 (OGJ, Nov. 6, 1995, p. 25). The project then called for a 300-km, $670 million line from the Bulgarian port of Burgas to the Aegean Sea port of Alexandroupolis (see map, p. 29). Russian oil could then be sent across the Black Sea by tanker from Novorossiisk to Burgas, then make the rest of the journey to western markets, bypassing the Bosporus Straits tanker route.

In its latest effort to push the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline, state-owned Hellenic Petroleum SA (HP) has repositioned the project as a Caspian region crude export alternative.

Greek pipeline prospects

Conceived to alleviate pressure on the congested and hazardous Bosporus Straits, just when the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline will become a reality depends on unfolding geopolitical events in the region. But for Yannis Prodromidis, director of external affairs at HP, the project makes sound sense.

"When new discoveries in the Caspian area came to light, we understood that the Bosporus would be a limiting factor in getting the oil out to its markets," he told OGJ recently. "And then came Turkey's arguments expressing fear of a major pollution."

Those fears proved well-founded when the Russian tanker Volgoneft 248 ran aground in the Sea of Marmara, spilling much of its heavy fuel oil cargo onto Istanbul's shoreline. She was the third tanker to run aground off Istanbul in December 1999 alone.

Turkey has frequently voiced its concern over these risks but, under the 1936 Montreaux convention, free passage through the straits is guaranteed to all merchant ships in peacetime. Furthermore, pilotage is not compulsory.

Project participants

The Burgas-Alexandroupolis project was conceived by Greece's giant Latsis group. Feasibility and basic design studies, supervised by partner HP, are now complete.

The Transbalkan Pipeline Co., which will construct and operate the pipeline, is being formed.

In addition to Latsis and HP on the Greek side are Kopelouzos and Promotheus Gas. The Bulgarian partners have been unofficially announced as Lukoil Bulgaria, Bulgar Gas, and the Port of Burgas. On the Russian side are Rosneft, Transneft, Slavneft, Stroitransgas, and Orel-Oil.

Just how the equity will finally be divided is the subject of some conjecture. It was agreed last year that the Russian partners would take 50%, the Greeks 30%, and the balance divided between the Bulgarians and Chevron Corp., operator of Kazakhstan's Tengiz oil field. Following recent Bulgarian objections that their stake was too small, the Russians have apparently agreed to relinquish a 10% interest from their share to the Bulgarians, who will now have a 20% stake, leaving Chevron with 10%.

"Construction can only start after the partners reach agreement with parliaments in Bulgaria and Greece and a final agreement is reached with the oil companies to use the pipeline," Prodromidis said. "Only if we secure these commitments will we start construction."

It is intended that 20% of the pipeline's $688 million currently estimated cost will be covered by the partners, 20% by European Union-allocated Greek funds, and the remainder from market loans.

The pipeline's initial design capacity is put at 10-15 million tonnes/year, expandable ultimately to 35 million tonnes/year after 18 years (Table 1).

Construction is expected to take no more than 21/2 years, allowing for the granting of local permits and licenses. The marine installations are likely to entail single buoy mooring systems accommodating at maximum 150,000 dwt tankers at each end of the pipeline. "The project is aimed at the international market, so it will be a buried pipeline with full cathodic protection," he said. "And we think that, with a shorter route and especially the application of local prices and local works, we can lower the cost further."

Caspian exports

Prodromidis expects production in the Caspian area to increase rapidly in the coming years: "The projects in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan have been delayed due to falling demand, but our assumption is that the line of incremental demand, which was interrupted, will continue again with the same slope but with a lag of, say, 5 years."

While no one can say for sure what is the ultimate oil export capacity of the Bosporus transit route, current oil throughput is estimated at 60 million tonnes/ year-added to which is a growing traffic in nonoil trade and the 1,500 or so daily ferry crossings. It is estimated that a critical level will be reached at 80 million tonnes/year, hence the need for a secondary pipeline.

"The projections from Kazakhstan's Tengiz field alone are estimated at 25-30 million tonnes/year in the initial stages," said Prodromidis, "and the existing pipeline capacity from Baku to Supsa is going to be tripled from 5 to 15 million tonnes. Our pipeline envisages carrying mainly Kazakhstan crude that will find its way to the east coast of the Black Sea and thence by sea to Burgas."

As to the Baku-Ceyhan project, Prodromidis noted, "For many years, the American administration has been pushing particularly the Azeris to move their oil not over Russian territory via the northern route to Novorossiisk, not even over the western route through Georgia to Supsa-which they consider can also possibly be influenced by the Russians-but via Turkey to Ceyhan. I can see their reasoning, because a lot of money is going to be invested by American companies, and they want not just an economic but a secure route. On the other hand, history tells us that the Russians have never created obstacles or failed to meet their obligations when moving oil or gas.

"And it is the investor-including his shareholders-who has to decide how and where to invest. If there is a final difference in delivered cost, Black Sea vs. Ceyhan, of, say, $10/tonne-and we believe it would be more-and that is applied to an annual volume of 50 million tonnes, then the shareholders will ask why such a decision is being taken.

"I cannot imagine the situation with the Baku-Ceyhan project when, especially at the start, the operating company will have, on the one hand, to repay the banks and, on the other hand, the throughputs will be much lower in the initial stages and the transit fees higher. So I think it is not an easy project, unless Turkey will guarantee that [it] will pay the difference."

"There are other plans, of course, such as the Burgas-Vlore [Albania] pipeline which in my view is dead before it is born (see map, this page). Consider the length of our pipeline. It is 280 km, and the maximum altitude is 312 m. There [in Albania], you will face 913 km and altitudes of up to 2,500 m."

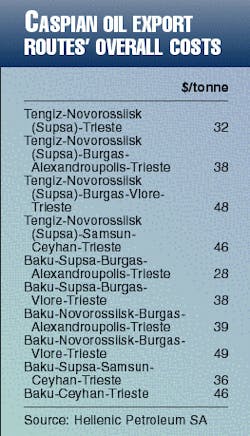

HP thus hopes the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline will sell itself on the strength of economic common sense (Table 2).

Yannis Prodromidis

Hellenic Petroleum SA

Director of External Affairs

It is the pipeline investor-including shareholders-that must decide how and where to invest. If there is a final difference in delivered cost, Black Sea vs. Ceyhan, of, say, $10/tonne-and we believe it would be more-and that is applied to an annual volume of 50 million tonnes, then the shareholders will ask why such a decision is being taken.