Restructuring of China's oil industry continues as doubts regarding its success loom

FACTS Inc.

Honolulu

This article is based on an advisory issued by Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services Inc. (FACTS Inc.), a consulting group directed by Fereidun Fesharaki.

Reform of the Chinese oil industry has entered its second phase since early 1999. The target is to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of the state oil companies and partially privatize them by offering shares to public investors, both domestic and international.

Although some China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) and China Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec) subsidiaries have long had their shares listed on domestic and overseas stock markets, what is different this time is that two single shareholding companies are being formed at the national level: one under CNPC (set up recently) and another under Sinopec (to be created soon). China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) also has its own shareholding company.

These shareholding companies will group together their respective key subsidiaries for stock listing.

CNOOC is at a more advanced stage than both CNPC and Sinopec in the restructuring process. However, CNOOC's failure to launch its first initial public offering (IPO) in mid-October has alarmed both CNPC and Sinopec, forcing them to be more cautious and sensitive with regard to the timing and nature of their launching.

Largely excluded from the pro- cess-except for a few consulting, financial, and accounting firms-many international energy-related companies, watching from the sidelines, are skeptical about the planned overseas listings of CNPC and Sinopec.

The primary reason for the state oil companies' recent move toward further restructuring is the need to reform state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China, where all four domestic oil companies are SOEs. Another reason is China's upcoming membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO).

While the idea for the second phase of restructuring is to separate money-making assets from money-losing functions, thus making the firms more attractive to investors, many other fundamental problems of the Chinese oil industry remain unsolved.

Among other key changes in the industry, the most significant is perhaps the proposed new fuel tax on gasoline and diesel-approved by the Chinese parliament-which will impact the pricing of and demand for transportation fuels in China.

As for the regulatory structure, it is not entirely impossible that the State Administration of Petroleum and Chemical Industries (SAPCI) will be abolished in a few years, or even earlier.

Background

The Chinese oil industry promises to be dramatically different after the second phase of the restructuring of the state oil companies is completed in 2000.

The first phase started in March 1998. While the majority of the restructuring targets for the first phase were largely completed by early 1999, there is still unfinished business, including how locally owned small refineries should be divided among CNPC and Sinopec and how many of them should be shut down completely.

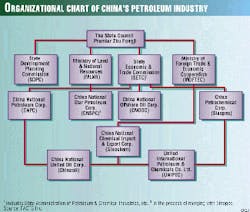

During the first phase, the four state companies-CNPC, Sinopec, CNOOC, and China National Star Petroleum Corp. (CNSPC)-were reorganized. The first two in particular were reorganized largely along geographical lines. Within their jurisdictional areas, the restrictions on what type of oil business a company can operate, ranging from exploration to marketing, were removed.

The second phase of the restructuring started in early to mid-1999. The buzzwords have been "asset reorganization," "debt restructuring," "stock listing," etc.

In addition to asset restructuring and stock listing, the most significant organizational change in the Chinese petroleum industry is the planned merger of CNSPC-the smallest state oil company in China-and Sinopec, announced in late November 1999.

As the reform continues to unfold, many issues are still unresolved and many questions unanswered. However, some of the key developments-mostly in 1999, and during the past couple of months in particular-may give the international energy community a better understanding of how the structure of China's oil industry will look in 2000.

Of these key developments, which are the focus of this article, the most significant are the stepped-up efforts of the state oil companies for stock listing, CNOOC's failed IPO attempt, the reaction of international energy investors to the planned oil stock listing, and the merger of Sinopec and CNSPC.

Fig. 1 illustrates the organizational structure of China's petroleum industry before the CNSPC-Sinopec merger.

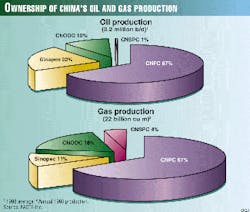

Shares of oil and gas production by each individual state oil company are shown in Fig. 2. Sinopec and CNPC are the only refinery operators among the four state firms, with the former accounting for 55% and the latter 45% of the 4.9 million b/d of crude distillation capacity operated at the beginning of 1999. The additional 300,000-600,000 b/d of capacity attributable to locally owned, small refineries is being closed down or will be merged with either CNPC or Sinopec in a variety of ways.

CNPC, Sinopec stock listing

Although some CNPC and Sinopec subsidiaries-such as Dagang Oilfield, Jilin Chemicals, Zhenhai Refinery & Chemicals, Shanghai Petrochemicals, and Yizheng Chemicals-have long had their shares listed in domestic and overseas markets, two single national shareholding companies are now being formed for the purpose of creating consolidated overseas listings.

During the past several months, strategic groups specially assembled by CNPC and Sinopec worked long hours studying the issues of asset reorganization, shareholding company formation, and overseas listing.

CNPC is ahead of Sinopec in the process. On Nov. 6, 1999, CNPC formally set up a new company, China Oil & Gas Stock Co. Ltd.-also called Petrochina-of which CNPC is the holding company. Petrochina will engage in oil exploration and production, refining and marketing, petrochemical sales, natural gas, pipelines, and other businesses within CNPC's jurisdiction.

Ma Fucai and Huang Yan, currently president and vice-president of CNPC, have been appointed, respectively, chairman and president of Petrochina. Shares of existing CNPC subsidiaries that are listed will be merged under Petrochina.

Sinopec is expected to follow the same procedure. As for the timing of the overseas listing, Sinopec plans to launch it sometime after March 2000.

Sinopec is expected to raise $6 billion through IPOs, while the size of CNPC's IPO is expected to be larger.

CNPC's overseas listings could be launched at any time, but this probably will not happen until March 2000.

If the overseas listings are successful, the state oil companies will eventually be partially privatized. Whether partial privatization-especially privatization at a level far below 50% of the asset-is the right approach to revitalizing the Chinese oil industry, it remains to be seen.

It is not clear whether the management of the subsidiaries will remain fully in the hands of Sinopec and CNPC after the stock listings, or whether investors will be allowed any role. To date, no management role has been given to investors in any of the CNPC and Sinopec subsidiaries that are currently listed in domestic and overseas stock markets.

Moreover, there is a big question as to whether the listing will be successful.

Lessons of CNOOC

Despite the well-publicized move by CNPC and Sinopec to turn a key part of their companies into shareholding entities with shares being purchased by domestic and foreign investors, it is by no means certain that the state oil company leaders are fully confident of what they are doing. Part of the reason is CNOOC's failure in the launch of its first IPO in mid-October 1999 in Hong Kong.

The state offshore oil company is actually ahead of both CNPC and Sinopec in the restructuring process involving overseas listing of company stock. In August 1999, CNOOC formed the new company, China Offshore Oil Corp. Ltd. (COOC), in which CNOOC is a holding company. The target of CNOOC is to hold 75% of the equity interest in COOC after successful listing of the company stock in overseas markets.

CNOOC's original plan was to issue $2 billion worth of shares first in Hong Kong and then in New York. After a steep cut of the initial issue price, CNOOC reduced its offering to $1 billion and then called off the Hong Kong offering on Oct. 15, 1999. The company has also indefinitely postponed the New York IPO that was planned for Oct. 20.

CNOOC's failure alarmed both CNPC and Sinopec, forcing them to be more cautious about the timing and nature of their stock launchings.

Among the many reasons that CNOOC's IPO was halted, adverse stock-market conditions at the time of the launch is the major one. That particular week in October was one of the worst weeks on Wall Street in recent history. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 628 points, losing 5.9% of its value during the week.

In Hong Kong, CNOOC's offer had to compete with several IPOs from other companies on the same day. In addition to the market-related factors, CNOOC's internal plans for using part of the funds from the IPO to establish a large retirement and replacement fund for exiting retirees and employees likely to lose their jobs due to restructuring are also blamed for investors' low interest in the offering.

Because of CNOOC's failure, CNPC and Sinopec have decided that timing is important for their IPOs. Any time between now and the end of February is not regarded as appropriate for the listing.

As for CNOOC, the launch of a $2.5 billion IPO has been rescheduled for late January or early February.

Investor skepticism

Many international energy companies that are potential buyers of the listed Chinese stocks and that have business or representative offices in Beijing remain very skeptical that the planned overseas listing of CNPC and Sinopec will be an instant success.

CNPC and Sinopec want to present to the public and to business circles two freshly organized shareholding companies in order to score successfully in their IPOs. But potential foreign investors still have plenty of worries. Among the key ones is whether Chinese state oil companies can really compete and survive, as they claim they can, in the free market.

In the past, although it was often difficult for foreign companies to compete with Chinese state oil firms that enjoy so many privileges, at least they did not have to worry about business losses if the Chinese companies failed. By offering corporate shares without allowing any participation in the corporate management, the Chinese state oil companies will have to prove to the potential foreign investors that their business operations are competitive, transparent, and well-managed. They also have to prove that their shares have growth potential.

Whether CNPC and Sinopec already have these qualifications is highly questionable.

The last-minute postponment of CNOOC's IPO has shaken the confidence of many investors, making it more difficult for CNPC and Sinopec to launch successful IPOs.

Reform, WTO membership

The question that needs to be asked is why the Chinese state oil companies decided to move to Phase 2 reforms that are full of uncertainties. The profound reason is the need to keep pace with the overall reform of state-owned enterprises in China.

At the end of 1998, the Chinese government made SOE reform one of the major tasks for 1999. To reduce the huge debts owed by SOEs and recover money lost as a result of bad loans issued by state banks, the Chinese government initiated a "debt-to-equity" scheme in early 1999 to convert a portion of the SOEs' debt to equity shares to be owned by four state asset management companies individually established by the four largest government-owned banks. Premier Zhu Rongji's cabinet also promised to provide state replacement funds to SOEs that agree to go through company restructuring by reducing workforce and reorganizing debt.

Under these circumstances, the state oil companies were given a rare chance to restructure their companies, with financial support from the government. The transformations include separation of core business from noncore business and reduction of workforce. As a condition, the state oil companies have to dramatically improve their efficiency and become competitive enough to face international competition.

The government's offer is great, but the risk is also high. To grab this opportunity, the state oil companies appear to have no choice but to proceed with reorganization.

Another reason for the second-phase reform is China's attempt to become a member of the WTO. On Nov. 15, 1999, China and the US finally reached a landmark trade agreement on the issue of China's membership in the WTO, paving the way for China to enter the organization after 13 years of marathon-style negotiations.

While China's WTO membership-which leads to market and financial liberalization in the country-will not pose immediate, direct challenges to China's oil and gas industry, it is understood that the state oil companies have only a small window of opportunity (a couple of years) to reform their structures and improve their efficiencies before facing stronger challenges from international investors in petroleum and petrochemical trading, marketing, storage, and even oil and gas pipelines, under future and more-liberalized WTO rules. For this reason, joining WTO has become another reason why the Chinese oil companies have to act now, before it is too late, to improve their efficiencies.

Fundamental problems

While the idea for the second-phase of restructuring is to separate money-making assets from money-losing functions in order to make the firms more attractive to investors, many fundamental problems in China's oil industry have not been addressed by the reform, as planned.

Briefly speaking, high costs, inefficient operations, contradictory government policies, administrative price-fixing, and other regulatory protections are some of the most serious problems facing the Chinese state oil firms, and the industry as a whole. The current reforms are aimed at improving the efficiency of the state oil companies but have not yet addressed other fundamental issues at all.

The Chinese oil market has been largely regulated since May 1994. The most tightly controlled areas are pricing (including wellhead, ex-refinery, wholesale, and retail prices) and importing and exporting of crude oil and primary refined products.

The rules and regulations governing the latest price reform in June 1998, which promised to link domestic oil prices with international (Singapore) prices, were eventually applied to crude oil only. The state-set retail prices for major refined products have been changed little since mid-1998. Instead, during the second half of 1998 and onward, the government has taken a series of measures, including crack-downs on oil smuggling, suspension of commercial bonded storage operations, closure of locally owned small refineries, and direct bans on gasoline and diesel, to support the state regulated prices and protect the interest of state oil companies.

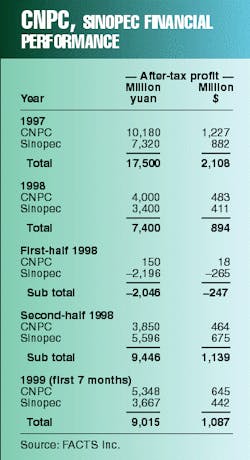

The table on this page shows that CNPC's and Sinopec's profitability can be significantly affected by the government's efforts to support the high domestic prices of refined products. The sharp contrast between profits during first half 1998 (when the firms lost a combined $247 million) and the second half (when they made $1.14 billion) is the best example to demonstrate how the Chinese government helped the state oil companies turn around at a critical time.

For 1999, Sinopec's profit target is 6-7 billion yuan ($725-845 million). During the first 10 months, the petrochemical company had already accumulated 5.95 billion yuan in after-tax profits.

As for the government policies governing oil sector development and markets, they are often contradictory. During the past year, in particular, the regulations of the oil market and protection of the state oil companies have been moving in a totally different direction from China's open policies for attracting foreign investment and improving the business environment.

For over 2 decades, the Chinese government has stressed the importance of continuing and deepening economic reforms. In the oil industry, however, more restrictive regulations than market-opening measures have been introduced and implemented in the recent past, leading to a typical phenomenon of "one step forward, two steps backward" in China's petroleum industry reforms.

One of the major problems associated with market protection-especially through price-fixing and trade restrictions-is perceived uncertainty, especially in China, where many regulations and restrictions are called "provisional." Yet it has never been clear when the protections will be ended.

Although high state-set prices and restrictions on oil imports provide higher profit margins for the state oil companies, they also create uncertainties about the future of the firms. What will happen to the state oil companies if the prices are reduced or if trade protection is ended? Unless it is clear that the protection is short-term in nature and, indeed, provisional, with a clear ending date, it may run counter to the intended target of the current round of industrial restructuring for the purpose of reducing operational costs and improving efficiency.

For potential international investors facing investment decisions involving hundreds of millions of dollars, the long-term growth potential and transparent company management are more important than short-term gains from government price and trade protection.

Sinopec-CNSPC merger

Although CNSPC is the smallest Chinese state oil firm (Fig. 2), it has over 300,000 employees, about the same as CNOOC.

Initially, CNSPC was placed under the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources. Later-like CNPC, Sinopec, and CNOOC-the company was supervised by SAPCI.

After months of rumors, it is now confirmed that CNSPC will be merged with Sinopec. In fact, it is a takeover of CNSPC by Sinopec.

A year ago, FACTS Inc. argued that the four-oil-company structure in China was unstable and unsustainable because of its huge imbalance.1 Now, the four state companies will become three.

FACTS Inc. believes that the Sinopec-CNSPC merger is a positive development in China's oil industry. In our opinion, there is no genuine competition among state oil companies, especially in a tightly regulated and protected market.

Other changes

Among other key changes in the industry, the most important one is perhaps the passing of the amendments to the long-delayed Highway Law by the National People's Congress (the Chinese parliament) at the end of October 1999.

Adoption of the amendments is paving the way for the government to start levying a controversial fuel tax on gasoline and diesel. The amendments set the highway tax on gasoline at 1.15 yuan/l. ($22.10/bbl). The rate for diesel is likely to be 1.0 yuan/l. ($19.20/bbl).

It is still unclear exactly how the law is going to be implemented, although President Jiang Zemin's decree stipulated that the law and amendments became effective immediately after passing.

There is no doubt that retail prices for transportation fuels in China will increase sharply following full implementation of the Highway Law with the fuel tax provisions. The increase, however, will be partially or fully offset by the expected decreases in all types of surcharges and fees collected by various central and local government authorities. As a result, the ultimate effect of the fuel tax on China's transportation fuel demand needs to be carefully studied.

As for the organization of China's oil industry, in addition to the Sinopec-CNSPC merger, another likely change during the coming years is the possible abolishment of SAPCI.

When SAPCI was established in March 1998, its duration was set at 3 years, and the mandate was to exercise government functions that were previously incorporated in the state oil companies. After less than 2 years of operation, the relationship between the state oil firms (CNPC and Sinopec, in particular) and SAPCI has been uneasy.

The reason is that SAPCI is semi-independent but is also affiliated with the larger and more influential State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC). It is often difficult for the state oil companies to be supervised or governed by three government agencies-SETC, the State Development Planning Commission (SDPC), and SAPCI.

Some of the supervisory functions existed in SETC and SDPC, and the de facto policy-setting role partially exercised by the state oil firms, has made the semi-independent SAPCI redundant.

Recently, one senior deputy administrator of SAPCI-Yan Sanzhong, a former Sinopec vice-president-was appointed vice-president of CNPC; his SAPCI position remains to be filled.

By many accounts, if SAPCI indeed is dissolved after its 3-year assignment, the agency is likely to be made a regular department within SETC, performing the role of supervising Chinese state oil companies for SETC.

Conclusions

There remains unfinished business under the Phase 1 restructuring of China's oil industry, including the status of locally owned small refineries and the gradual establishment of CNPC's and Sinopec's monopoly roles in the wholesale oil business. While it is almost certain that organizing state oil companies along geographical boundaries cannot solve many of the problems facing the Chinese state oil industry, and the success of such reorganization is questionable, the second phase of restructuring has begun, bringing with it even more questions and uncertainties regarding the future of the Chinese oil industry.

In China, very often the problem is contradictory policies and rules set by the government. On the one hand, the Chinese government wishes to promote the growth of the economy and improve the efficiency of SOEs by welcoming foreign investment and competition.

On the other hand, these SOEs often need government protection, leading to short-term government policies and regulations that benefit SOEs but bias against foreign and private-sector investors. That is what has happened in the petroleum industry during the past several years.

In addition, the regulated oil price and trade regime in China in fact protect the weak and inefficient operations of the state firms, yet the issues of price and trade protection are not adequately addressed at the current round of restructuring and reforms.

In short, as the Chinese petroleum industry continues to be restructured and prepares itself for the 21st Century, it is fair to say that foreign investors have every right to cast their doubts on the success of the second-phase reforms. They will continue to guard their pockets until it is clear whether the investments in the planned IPOs are worthwhile.

Reference

1. Fesharaki, Fereidun, and Wu, Kang, "Revitalizing China's Petroleum Industry through Reorganization: Will It Work?" OGJ, Aug. 10, 1998, p. 33.