Emerging 'triple bottom line' model for industry weighs environmental, economic, and social considerations

At the confluence of corporate environmental, economic, and social engagement, a new paradigm has emerged: the triple bottom line (TBL).

What is the relevance of this approach to the oil and gas sector? Is it just didactic tub-thumping from eco- intellectual elites, or does it contain deeper strategic or even practical meaning? And what are petroleum companies doing about it anyway, if anything?

Former adversaries in the battle over corporate environmentalism are increasingly finding common ground on which to stage debate and forge more-constructive relationships. The driving force behind this new and still slightly paranoid spirit of détente is the pursuit of sustainable development, an approach that draws together into a single unified developmental model many of the complex environmental, social, and economic issues facing society as a whole.

Despite its rather grail-like qualities, sustainable development has come a long way since its genesis at the Rio de Janeiro earth summit in 1992. It now forms the basis for environmental policy in many countries as well as the intellectual cornerstone on which much international environmental and developmental activity is founded.

Incorporating the tenets of sustainable development into the world's economic constitution is widely considered to be imperative to future global prosperity and will require the worldwide mobilization, reorientation, and focus of enormous amounts of financial and human capital.

In a world where governments everywhere command fewer resources and less legitimacy as direct economic actors, the private sector has begun to shoulder more of the burden for this unprecedented social investment.

Currently, for example, about 2,000 companies have signed the International Chamber of Commerce's (ICC) business charter for sustainable development. More than 120 of these firms have become active participants at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) in Geneva.

Main issue

At the core of the sustainability agenda is the issue of how to harness the resources of the private sector to these new social and environmental imperatives without compromising-and ideally enhancing-economic profitability and value creation.

Here's where TBL enters the picture.

First coined by John Elkington and his team from the UK group SustainAbility Ltd., the TBL approach is designed to help companies knit the three components of sustainable development-economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental protection-into their core operations and essentially make the jump from sustainability theory into practice.

Aside from the work of SustainAbility, several leading initiatives are under way to develop the TBL approach. These include the World Resources Institute sustainable enterprise initiative; the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies-sponsored global reporting initiative, which is to include TBL accounting and reporting on its future agenda; and United Nations environmental program initiatives on capital markets and the environment.

WBCSD is also spearheading a project to develop meaningful ecoefficiency indicators for application in benchmarking performance, and the ICC is aiming to incorporate more social factors into its primarily environment-focused business charter.

TBL's aim

The focus of the TBL process is, by necessity, entirely compatible with the goal of business itself; namely, the creation of long-term shareholder value.

In fact, proponents contend, the TBL approach is merely an extension of the scope and time line over which a shareholder's interests are assessed. The underlying rationale is that companies emphasizing the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of their business will be in a much better position to build competitive advantage, generate long-term wealth creation, and sustain profitability than companies that do not.

The argument is certainly a strong one. Major corporations remain abjectly dependent on their "social license to do business," a license that can be revoked summarily over perceived environmental transgressions.

Few would dispute that customers, employees, suppliers, regulators, and other key stakeholders can all be positively influenced by a superior environmental track record.

And many companies are already producing top-line revenue growth with new products and services predicated on environmental out-performance, making a mockery of the notion of "environment as a pure cost center" as they go.

Research in this field indicates that the correlation between financial and environmental out-performance is invariably a positive one and is strongest in high-impact sectors such as chemicals, petroleum, forest products, and electric utilities. What is more, this correlation seems set to strengthen in the future as the forces of tighter international environmental standards, tougher disclosure requirements, and globalized competition combine to increase the financial and competitive premium provided by superior environmental engagement.

The petroleum industry certainly provides rich pickings for TBL enthusiasts. Historical environmental liabilities, the management of wastes, chemical emissions and spills, and other compliance obligations place continual and increasing demands on oil and gas company management.

Tailpipe-emissions restrictions and gasoline standards have necessitated environmentally rooted expenditures unmatched in any other industry. The UN framework convention on climate change and the 1997 Kyoto protocol on reducing greenhouse gas emissions continue to lurk menacingly in the background.

From a social perspective, an uneasy dualism is emerging between the need for geographic diversification and competitive intensification on the one hand and that for greater corporate social and environmental accountability on the other. Expanding operations on Africa's West Coast, the Caspian Sea basin, Southeast Asia, the North Atlantic margin, and Latin America are all creating new and highly complex social challenges, often linked inextricably with environmental sensitivities.

These challenges will necessitate the deployment of increasingly sophisticated social and environmental impact mitigation and measurement tools, as well as a willingness to interact meaningfully with multiple stakeholders.

The revival of the US Alien Tort Claims Act by human rights activists seeking to bring civil claims actions against US firms operating in sensitive international situations has a distinct environmental dimension and could provide a powerful incentive for companies to redefine their monitoring requirements for overseas operations.

Pressures related to building and maintaining positive relationships and reputations with environmental groups, regulators, local communities, investors, and other stakeholders are also stronger than ever. As a consequence, environmental reporting has become an important means of displaying one's sustainability credentials and distancing oneself from the competition.

Finally, from an economic perspective, the use of more sophisticated accounting methodologies, such as economic value added (EVA) or market value added, that come closer to capturing true value creation can be particularly useful for demonstrating company out-performance in highly competitive commodity industries.

Integrating social and environmental externalities of the type outlined here into EVA-style methods would enhance their utility even more. Leading-edge investors and industrialists are also becoming increasingly aware of environmental and social factors as competitive phenomena rather than simply as regulatory or moral obligations.

From a company's point of view, trying to put a dollar value on environmental risks and opportunities is a potentially powerful, but so far, underutilized strategy for flushing out these latent competitive advantages.

The culture of change

What makes this agenda so compelling for the oil and gas sector is its contrast with the industry's own inherent program of transition-from onshore to offshore, from shallow water to deep, from industrialized world to developing world, from oil to gas, and ultimately from fossil fuel to renewables.

At first blush, therefore, the very notion of sustainability in the oil industry appears somewhat antithetical. For while fossil fuels will continue to dominate the energy supply in the short to mid-term, the shift away from the most polluting fuels towards more renewable forms of energy will inevitably pick up pace as existing and new technologies are further developed and become more cost-competitive.

It seems clear then, that what sustainability in the oil and gas sector really implies is sustainability in the supply of energy, not the supply of oil and gas.

In view of the complexity of these social, environmental, and economic challenges, it is perhaps not surprising that companies differ substantially in their stated understanding of sustainable development, their level of participation in the sustainability debate, and the extent to which they have been prepared to take action. A few companies have formally announced the adoption of policies either explicitly based on TBL or loosely associated with it.

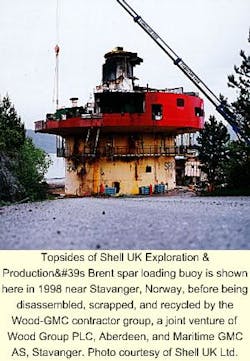

After a period of serious introspection following the Brent spar debacle, Royal Dutch/Shell is perhaps the most enthusiastic supporter of TBL. The company recently formed a social accountability team and began construction of a sustainable development management framework in partnership with SustainAbility.

Statoil AS has also begun to assess its performance in the financial, environmental, and social fields.

Neste Group, the Finnish energy and chemicals conglomerate, recognizes that investors are becoming increasingly interested in the environment and has devised a strategy aimed at achieving ecocompetitiveness.

BP Amoco PLC is also explicit in its mention of TBL, although the company's overall message is simpler and more straightforward: to have no accidents, do no harm to people, and do no damage to the environment.

Of course, these leading companies also distance themselves from the pack in other ways.

Shape of TBL

At the present time, key aspects of a TBL-type policy in the petroleum industry appear to be:

- Performance measurement that goes beyond compliance and pollutant emissions-though these remain critically important-to include basic qualitative social indicators as well as quantitative ecoefficiency metrics such as energy consumption, recycling, and materials use.

- The formulation of strategies for meeting future global energy needs that are compatible with environmental objectives, notably those regarding climate change.

- A consequent investment in natural gas, low or zero-emissions fuels, and renewable forms of energy.

- A sophisticated external communications program, in terms of TBL reporting and developing meaningful interaction with communities affected by operations.

Few companies would argue with BP Amoco CEO John Browne's goal of zero impact. In fact, mitigation and management of environmental im- pacts and operating risks rightly remain among the most important objectives for all companies.

However, it is clear that reducing environmental impact is only part of the TBL approach. All too often, companies misconstrue a business-as-usual policy of environmental-risk management as a push towards sustainable development.

Skeptics assign this misconception to deliberate heel-dragging on behalf of cynical, self-interested corporate leaders. While there may be some truth to this-and the level of ignorance of the concept of sustainability in some oil and gas firms is indeed truly astonishing-it is also true that many companies are pursuing activities and initiatives that relate closely to TBL but are not heralded as such.

Take as an example that pariah of the environmental movement: Exxon Mobil Corp. The company is routinely castigated in the environmental press, yet it has one of the strongest environmental-management programs and performance records in the business, is established as a leader in the development of low-emissions transportation fuels, is very well-placed in the global natural gas market, and is pushing ahead on numerous integrated-energy projects.

The company's work in developing the technological capacity to capture and store large volumes of CO2 during natural gas production could also be of benefit in a future greenhouse gas emissions trading market-should Exxon Mobil decide to take a more-positive role in such matters.

In fact, truly committed companies -and top-level buy-in is perhaps the critical factor in reorienting around TBL-might be surprised at how positive their position really is. The drive to go beyond compliance with environmental regulations and the push for greater efficiency and value creation on a sustainable basis for company shareholders-again, goals shared by most companies-have forced many companies to tease out the kind of efficiencies that TBL policies require.

The liberalization of global electricity markets has enabled many petroleum companies to move forcefully towards the creation of sustainable growth opportunities within the energy sector that simply did not exist 5 years ago.

Exxon Mobil's alliances with China Light & Power, Duke Energy Corp., and Tokyo Electric Power Co.; Chevron Corp.'s acquisition of Destec Energy Inc., which is the US's second largest independent power producer; and Texaco Inc.'s leading position in cogeneration and gasification are but three examples.

Programs under way

Many companies are already enhancing profits through innovative ecoefficiency programs in waste reduction, recycling, or the marketing of process by-products.

Sun Co. Inc. has gone so far as to establish a formal energy conservation program at all its refineries, executed through an energy conservation coordinator. Research and development of environmentally superior products are also prominent at many companies.

And many firms are already involving indigenous populations and non-governmental organizations more closely in the decision-making process and even having them serve as environmental monitors on certain projects.

This trend is illustrated by ARCO's establishment of local community outreach programs in Peru and Ecuador in connection with drilling operations, Exxon Mobil's work with Conservation International in Peru on the social and biological impact of its seismic work, and Occidental Petroleum Corp.'s utilization of the World Bank's socioeconomic expertise on their own development projects.

A look ahead

Viewing the petroleum industry as a whole, the continual backdrop of transition over and above the conventional business cycle coupled with the very uncertainty of oil and gas exploration itself has created a culture that is carefully comfortable with the management of change.

Compared with other industries, most oil executives view risk and uncertainty with a cool eye. Companies have been forced to innovate, they say, both technically by the hostile environments in which they operate, and strategically by the geopolitical importance of oil and the hegemony of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

It remains to be seen whether this culture is deep enough to make what seems to be the biggest transition of all -that to the sustainable energy company.

Although many uncertainties and difficult questions concerning sustainability remain, it is clear that the application of TBL represents a good starting point for petroleum companies to exert a more positive influence over their economic, social, and environmental destinies.

It is also clear that in the boardrooms of many companies, this process has already commenced.

The Author

Martin Whittaker is an environmental consultant, researcher, and senior analyst with Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Inc., New York, specializing in environmental risk, strategy, and finance. He holds a PhD in environmental science from the University of Edinburgh, an MSc in chemistry from McGill University, Montreal, and a BSc in chemistry from St. Andrews University in Scotland.