The Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which the US negotiated in December 1997, calls for industrial economies such as the US, Canada, Europe, and Japan (called Annex I or Annex B countries) to reduce their collective emissions of six greenhouse gases by an average of 5.2% from 1990 levels by 2008-12.

The US target is a 7% reduction from 1990 levels; this amounts to a projected 550 million tonne cutback in CO2 emissions relative to the projected amount in 2010. US Department of Energy estimates show that US emissions will be 40% above the Kyoto target by 2010. Many experts believe that the Kyoto Protocol (or "backdoor" implementation of the agreement through regulatory policies) would have potentially serious consequences for all Americans and that these consequences have not been fully analyzed and understood.

Four key issues for US climate policy are addressed here:

- The impact of CO2 reductions on US economic growth and the projected federal budget surplus.

- The Clinton administration's economic analysis of the Kyoto Protocol.

- Tax policy to encourage voluntary action to reduce CO2 emissions.

- Strategies for the future.

Macroeconomic effects of CO2 emissions cuts

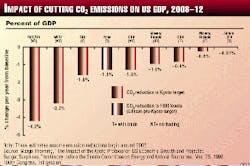

A wide range of models predict that reducing US CO2 emissions to either the Kyoto target (7% below 1990 emission levels) or even 1990 levels (President Clinton's pre-Kyoto target) would reduce US GDP growth significantly.

Research conducted over the past decade for the ACCF Center for Policy Research by top climate-change scholars such as Prof. Gary W. Yohe of Wesleyan University, Dr. Lawrence M. Horwitz of Primark Decision Economics, Senior Vice-Pres. Mary H. Novak of WEFA Inc., Prof. Richard Schmalensee of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Prof. Alan S. Manne of Stanford University, Dr. Richard Richels of EPRI, Dr. W. David Montgomery of Charles River Associates (CRA), Dr. Joyce Brinner of Standard & Poor's DRI (DRI), and others, concludes that the cost of reducing CO2 emissions in the near term would impose a heavy burden on US households, industry, and agriculture. In addition, the projected federal budget surpluses, which many hope will fund a more secure retirement for the baby-boom generation, are imperiled by slow growth in GDP stemming from CO2 emission reductions.

These studies, as well as the US Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration report released in October 1998, stand in sharp contrast with the optimistic projections contained in the Clinton administration's economic analysis prepared by the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), released in July 1998.

As CO2 emissions are reduced, economic growth would slow due to lost output, as prices rise for carbon-intensive goods-goods that must be produced using less carbon or more-expensive processes.

In dollar terms, estimates show that near-term reduction to the Kyoto Protocol target of 7% below 1990 levels would reduce US GDP by about 1-4%/year (Fig. 1). This translates into GDP losses of $100-400 billion/year (in inflation-adjusted dollars) vs. the baseline forecast for energy use.

Impact on US budget surplus

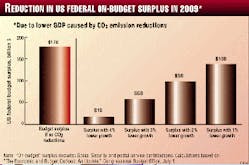

In light of the current debate about how to use the projected US federal budget surpluses, policymakers need to consider the potentially large negative impact on GDP growth and federal budget receipts of proposals that address the potential threat of global warming by requiring sharp, near-term cutbacks in CO2 emissions.

A report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) shows that, if economic growth were to slow relative to the baseline forecast, lowering GDP by 4% in 2009, the projected on-budget (excluding Social Security contributions) surplus virtually disappears, dropping from $164 billion to only $4 billion (Fig. 2). Similarly, if GDP falls by 3%, the surplus declines to $44 billion in 2009 (the last year of the current CBO forecast).

Therefore, implementation of the Kyoto Protocol would make it much more difficult to: sustain tax cuts, "save" Social Security, promote the retirement security of the baby-boom generation, or achieve other public policy goals; and it could require sharp changes in fiscal policy in order to avoid deficit spending.

Impact of international emissions trading

International trading of emissions permits would reduce the cost of near-term reductions considerably, although specialists agree that full global trading (involving developing countries such as China and India) is unlikely in the near term and that many complexities remain.

Even if developing countries agree to participate fully, two major obstacles to developing a trading system would remain: allocating CO2 emissions rights and distributing the revenue (Ellerman 1999). In addition, both developed and developing countries may find it difficult, if not impossible, to sell CO2 emissions credits because of energy's vital role in economic growth.

The costs of tradable permits to emit a ton of carbon are another measure of the burden that near-term emissions reduction would place on the US economy. These costs, which vary, depending upon how much trading takes place, are about $120-348/tonne for reducing emissions to 7% below 1990 levels.

The CEA's estimated tradable-permit price, which assumes full global trading, is only $14/tonne. (Note that the Clinton administration contemplates further reductions beyond the Kyoto target.)

Impact on wage growth, consumers

US consumers suffer declines in wage growth, and the distribution of income worsens under CO2 stabilization policies.

Yohe estimates that reducing emissions to 1990 levels (President Clinton's pre-Kyoto target) would reduce wage growth by 5-10%/year, and the lowest quintile of the population would see its share of the economic "pie" shrink by about 10% (Yohe 1997). Texas A&M University Prof. John Moroney estimates that US living standards would fall by 15% under the Kyoto Protocol compared with the base-case energy forecast (Moroney 1999).

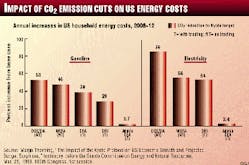

US households also face much higher prices for energy under near-term stabilization. A range of estimates by various analysts concludes that prices for gasoline would rise by anywhere from almost 30% to over 50% and that electricity prices would go up by anywhere from 50% to over 80% (Fig. 3). The CEA predictions (a 2.7% increase in gasoline prices and 3.4% higher prices for electricity) are far below those of widely respected climate policy modelers.

Competitiveness for industry, agriculture

US competitiveness also declines under near-term stabilization policies. Manne and Richels analyzed this question, and their model results suggest that the Kyoto Protocol could lead to serious competitive problems for energy-intensive sector (EIS) producers in the US.

Meeting the emissions targets in the protocol would lead to significant reductions in output and employment among EIS producers, and there would be offsetting increases in countries with low energy costs. US output of energy-intensive products-such as autos, steel, paper, and chemicals-could be 15% less than under the reference case by 2020 (Manne and Richels 1999). In contrast, countries such as China, India, and Mexico would increase their output of energy-intensive products. In its present form, the protocol could lead to acrimonious conflicts between those who advocate free international trade and those who advocate a low-carbon environment, Manne and Richels conclude.

US agriculture would also lose competitiveness if the US were to comply with the Kyoto Protocol. A study based on the DRI model by Terry Francl of the American Farm Bureau Federation, Richard Nadler of K.C. Jones Monthly, and Joseph Bast of the Heartland Institute (FNB), predicts that implementation of the protocol would cause higher fuel oil, motor oil, fertilizer, and other farm operating costs (Francl, Nadler, and Bast 1999). This would mean higher consumer food prices and greater demand for public assistance with higher costs. In addition, by increasing the energy costs of farm production in America while leaving them unchanged in developing countries, the Kyoto Protocol would cause US food exports to decline and imports to rise. Reduced efficiency of the world food system could add to a political backlash against free-trade policies at home and abroad. Further, the higher energy costs, notes the FNB analysis, together with the reduced domestic and export demand, could lead to a very severe decline in investment in agriculture and a sharp increase in farm consolidation. Small farm numbers likely would decline much more rapidly than under baseline conditions, while investment even in larger commercial farms likely would stagnate or decline.

The FNB analysis, which concludes that US agriculture would be adversely affected by the Kyoto Protocol, stands in sharp contrast with the May 1999 report by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which finds that the Kyoto Protocol would have "relatively modest" impacts on US agriculture.

The USDA report is seriously flawed for two reasons, according to a new analysis by Francl. First, the USDA report relies on the unrealistic assumptions about the impact of the Kyoto Protocol on energy prices contained in the administration's 1998 CEA analysis. Second, the USDA report makes the heroic assumption that US farmers will have unrestricted access to carbon credit trading (Francl 1999).

Flaws in the CEA analysis

The CEA's July 1998 economic analysis of the impact of reducing CO2 emissions to 7% below 1990 levels is seriously flawed for three reasons.

First, CEA cost estimates assume full global trading in tradable emissions permits (including trading with China and India). Most top climate policy experts conclude that this assumption is extremely unrealistic, because the protocol does not require developing nations-which will be responsible for most of the growth in future CO2 emissions (Fig. 4)-to reduce their emissions, and many have stated that they will not do so. Second, the Administration's (CEA) cost estimates assume that an international CO2 emissions trading system can be developed and operating by 2008-12. This assumption is unrealistic, according to Ellerman's (1999) analysis. Third, the cost estimates are based on the Second Generation Model (SGM) developed by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. The SGM appears to assume costless, instantaneous adjustments in all markets; the model is not appropriate for analyzing the protocol's near-term economic impacts, according to CRA's Montgomery (1999). As Massachusetts Institute of Technology Prof. Henry Jacoby (1999) observes, there are no short-term technical changes that would significantly lower US carbon emissions.

Tax policy, voluntary action

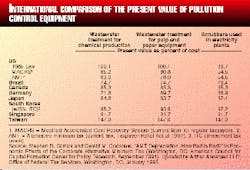

Current US tax policy treats capital formation-including investments that increase energy efficiency and reduce pollution-harshly compared with other industrialized countries and to our own recent past. For example, before the 1986 Tax Reform Act (TRA '86), the US had one of the best capital cost-recovery systems in the world.

Under the strongly pro-investment tax regime in effect during 1981-85, the present value of cost-recovery allowances for wastewater treatment facilities used in pulp and paper production was about 100% (meaning that the deductions were the equivalent of an immediate write-off of the entire cost of the equipment), according to an analysis by Arthur Andersen LLP.

Under TRA '86, the present value for wastewater treatment facilities fell to 81%, dropping the US capital cost-recovery system to near the bottom of an eight-country international survey (see table). Allowances for scrubbers used in the production of electricity were 90% before TRA '86; the present value fell to 55% after TRA '86. As is true in the case of productive equipment, both the loss of the investment tax credit and the lengthening of depreciable lives enacted in TRA '86 raised effective tax rates on new investment in pollution-control and energy-efficient equipment. Slower capital cost recovery means that equipment embodying new technology and energy efficiency will not be put in place as rapidly as it would under a more-favorable tax code. A variety of tax incentives such as partial expensing, accelerated depreciation, tax-exempt bond financing, or more-generous loss carrybacks that reduce the cost of capital for voluntary efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions could be more effective than the "credit for early action" regulatory framework proposal currently before the US Congress.

Strategies for the future

If, as knowledge of climate systems increases, policy changes to reduce CO2 emissions become necessary, these changes should be implemented in a way that minimizes damage to the US economy. Above all, experts agree that voluntary measures clearly and cost-effectively reduce the growth in greenhouse gas emissions, as the US Second National Communication to the Framework Convention on Climate Change noted in 1997. Modifications to US tax policy that reduce the cost of capital for energy-efficient investment should be part of the voluntary measures.

Reducing global CO2 emissions should be a gradual process, according to Pacific Northwest National Laboratory's Dr. Jae Edmonds, James Dooley, and Marshall Wise (1997). Moreover, a new study by Edmonds, Dooley, and Dr. Sonny Kim (1999) concludes that the introduction of carbon-capture and sequestration from central power facilities, the introduction of hydrogen fuel cells as an option for both power generation and transport, sequestration of carbon in the soil, and afforestation and reforestation would enable the economy to rely less heavily on carbon-neutral technologies such as commercial biomass harvesting and solar power (which are at an early stage in their technological development) to achieve a particular concentration level. For example, carbon sequestration at power plants and fuel cell use for electric power generation and transportation could cut the present discounted cost of satisfying the 550 ppm-by-volume constraint by more than 60%.

Conclusion

In short, the consensus of these noted climate-policy scholars is clear. Given the need to maintain strong US economic growth to address such challenges as a growing population, "saving" Social Security, the retirement of the baby boom generation, and a persistent trade deficit, policymakers need to weigh carefully the Kyoto Protocol's negative economic impacts and its failure to engage developing nations in meaningful action. Adopting a thoughtfully timed climate-change policy-based on accurate science, improved climate models, global participation, and new technology-is essential, both to US and global economic growth and to eventual stabilization of the carbon concentration in the atmosphere, if growing scientific understanding indicates such a policy is needed.

Bibliography

Climate Action Report. Second national communication submitted to the Framework Convention on Climate Change by the US Department of State. 1997.

Congressional Budget Office. The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Year 2000-2009. January 1999.

Corrick, Stephen R. and Gerald M. Godshaw. AMT Depreciation: How Bad Is Bad? In Economic Effects of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax, pp. 2-31. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1991.

Council of Economic Advisers. The Kyoto Protocol and the President's Policies to Address Climate Change: Administration Economic Analysis. July 1998.

Edmonds, Jae, James Dooley, and Sonny Kim. Long-Term Energy Technology: Needs and Opportunities for Stabilizing Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 81-107. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Edmonds, Jae, James Dooley, and Marshall Wise. Atmospheric Stabilization and the Role of Energy Technology. In Climate Change Policy, Risk Prioritization, and US Economic Growth, pp. 73-94. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1997.

Ellerman, A. Denny. Obstacles to Global CO2 Trading: A Familiar Problem. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 119-132. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Francl, Terry. 1999. "The Kyoto Protocol and US Agriculture: An Update on Research Findings." Working paper, American Farm Bureau Federation, Washington, DC. May 18, 1999.

Francl, Terry, Richard Nadler, and Joseph Bast. The Impact of the Kyoto Protocol on Agriculture. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 185-190. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Jacoby, Henry D. The Uses and Misuses of Technology Development as a Component of Climate Policy. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 151-169. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Manne, Alan S. and Richard G. Richels. The Kyoto Protocol: A Cost-Effective Strategy for Meeting Environmental Objectives? In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 3-23. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Montgomery, W. David. Commentary. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 141-147. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Moroney, John R. Energy, Carbon Dioxide Emissions, and Economic Growth. In Climate Change Policy: Practical Strategies, pp. 41-62. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1999.

Thorning, Margo. The Impact of the Kyoto Protocol on US Economic Growth and Projected Budget Surpluses, testimony before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, 106th Congress, 1st session. Mar. 25, 1999.

US Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Office of Integrated Analysis and Forecasting. Impacts of the Kyoto Protocol on US Energy Markets and Economic Activity. October 1998.

US Department of Agriculture Office of the Chief Economist, Global Change Program Office. Economic Analysis of US Agriculture and the Kyoto Protocol. May 1999.

Yohe, Gary W. Climate Change Policies, the Distribution of Income, and US Living Standards. In Climate Change Policy, Risk Prioritization, and US Economic Growth, pp. 13-54. ACCF Center for Policy Research. 1997.

The Author

Margo Thorning is senior vice-president and chief economist of the American Council for Capital Formation, an influential business lobby and think tank that focuses on pro-capital formation tax and environmental policies. She also serves as director of research for the ACCF Center for Policy Research and coeditor of numerous books on tax policy and environmental policy. Previously, Dr. Thorning served in the US Department of Energy, the US Department of Commerce, and the Federal Trade Commission. She received a BA from Texas Christian University, an MA in economics from the University of Texas, and a PhD in economics from the University of Georgia.