Disease, Trauma Spur Health-Care Push For Oil Travelers, Expats

In contrast to safety, managment at upstream oil companies and their contractors finds it difficult to completely quantify the benefits of health-care programs for remote or hostile locations.

Safety can be documented. Injuries and fatalities can be easily counted, compared, and categorized. Trends can be tracked and changed, latent hazards eliminated.

But the results of a good health care program are difficult to quantify. How many cases of malaria, how many fatal heart attacks did it prevent? Its implementation cannot be measured in terms of additional feet drilled or barrels of oil or cubes of natural gas produced.

Its cost can. In fact, when things are going well in the health area, company medical directors often hear management say, "Why are we spending so much money on this?"

Unfortunately, it takes only a couple of emergency air evacuations, costing sometimes up to $100,000, or the return of an expatriate family well before assignment completion, perhaps for psychological or social reasons, to make clear the benefits of a broad and thorough health care program.

The upstream industry is moving into developing countries and regions where the medical infrastructure is virtually non-existent or where western medicine has never been practiced (nor wanted, in some cases).

Knowing this, key oil company staff members have at times rejected assignments when they find the company has not adequately covered their potential medical needs.

So, enlightened exploration and production (E&P) companies and their contractor allies are beefing up their health care programs and seriously studying organizational changes and methods of delivery. A recent conference sponsored and developed by Oil & Gas Journal (covered later) examined why and how they are doing this.

Incentives

There are numerous incentives other than diseases for developing strong medical support. Trauma from automobile and vehicle accidents in developing countries is the leading medical problem anywhere in the oil world, medical directors say.

Dr. Alison Martin, senior medical adviser for BP Amoco plc, who has traveled much of the third world to set up or support BP medical operations says, ironically, many people who buckled themselves and their children up at home change their attitude and stop when they go overseas.

In less-developed countries, people without any experience are driving huge trucks and causing horrific accidents.

In more-developed countries with money, such as some parts of the Middle East, local youths drive high-performance cars too fast.

What is frightening for survivors of accidents is the prospect of needing a transfusion of whole blood in a region rampant with AIDs and other diseases.

Another reason to set up a good medical program for hostile environments (which include passenger-jammed airplane cabins) is to keep the frequent international traveler in good health. There is a myth that modern science and technology have wiped out the threat of disease and the world is a safer place. A good vaccination program is all one needs.

Not true. There are no vaccines, for example, for malaria and dengue fever. And the mosquitoes that carry them, once thought to be controlled, are making a strong comeback.

A good program also reduces the chance of an employee going into a hostile environment, getting seriously ill, and claiming that the employer did not provide the immunizations or information to cope with that environment.

There was just such a celebrated case in Britain some 2 years ago when a trainee lawyer sued her firm for the equivalent of a $1 million. It had sent her to Ghana on assignment where she contracted dysentery from eating fresh barracuda fish. The disease incapacitated her and she was unable to work for months on her return to Britain.

She alleged her firm failed to warn her about the risk of eating certain food, failed to provide appropriate medical care, and would not return her to Britain as she requested after she developed diarrhea and stomach pains. A spokesman for the firm said it had no idea how sick she was and resisted the claim. The case was subsequently settled out of court.

Another factor pushing health care programs is the fact that some host country officials or politicians want their often impoverished citizens to have access to the paramedics, doctors, and medicine the oil venture has brought in to an area. For humanitarian, public relations, or business reasons, companies are compelled to address this expensive aspect of remote medicine.

Finally, some countries have rigorous health care requirements and regulations covering operators, drilling contractors, and other service companies. Norway has some of the toughest.

If one has a medical problem, offshore Norway is among the best places to be, with its mandated medical personnel, clinics, and helicopter access to good hospitals on shore-on a good day.

On a bad day, with a howling storm, mountainous seas, or fog, it can be the worst place. Heart attack and trauma victims have died because of 2 or 3 day weather delays when neither boats nor helicopters could reach the platforms.

Phillips' experience

Phillips Petroleum Co., which kicked off the North Sea boom with its Norwegian Ekofisk discovery in 1969, has compiled a remarkable body of statistics on illnesses and injuries.

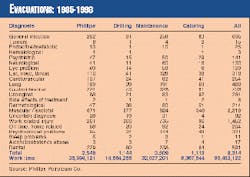

Table 1 shows the total number of evacuations from the Ekofisk field 1985-1998 by diagnosis and type of worker.

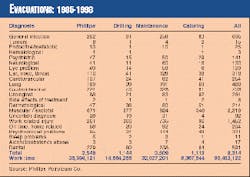

Table 2 shows the total number of consultations and diagnoses in the field for 1986-1998. The tables also show total work in the field in terms of man-hours and man-days.

Phillips has noted an increase in the amount of sick leave taken by hourly workers as percentage of total time worked 1992-1995. Because many workers went to work for the first time offshore in the early 1970s as the North Sea boom got under way, they are entering their 60s.

The offshore worker population is entering this age group in both Norwegian and British waters. This is a factor in the increasing sick-leave time, Phillips believes. Medical departments that must make adjustments for this trend are therefore feeling the impact.

Quest for a model

A corporate medical program set up for employees assigned to remote areas involves more than physicians and medical professionals. Dr. M.J. Gilbert, chief medical adviser for BG plc, has given thought to the formal framework that defines the responsibilities of the various corporate parties in relation to occupational health, specifically that involving expatriates.

He is based at BG's headquarters in Reading, a short train ride west of London. He looks at the issue from the vantage of service for Shell International (beginning in 1970) in Nigeria, Oman, Brunei, and London. He was for a time medical adviser for Shell's tanker fleet.

He joined BG in 1992. Since then, in addition to his managerial responsibilities, he has investigated medical resources in a number of developing countries for BG, most recently Bolivia.

BG has gone through a major culture change. Once a very domestic British state-owned natural gas distributor, it is now a major international player with assets in 17 different geographic areas in both hemispheres.

The accompanying box presents Gilbert's views on the responsibilities of occupational health and human resources personnel, country managers, and expatriates to make the system work.

BG managers, whether they run an office in Basingstoke, England, or a gas field in Bolivia, have received two corporate directives concerning employee health.

One is to ensure that a health-management system that complies with company policy and commitment to the health and well being of its employees is established and meets the needs of the particular operation.

The other is a health-surveillance directive to ensure that employees are fit to carry out their assigned tasks and suffer no detrimental long-term effects on their health or well being related to their employment.

This requires, in short, each business unit to collect health information regularly and report incidents of occupational-related disease. Compliance is still patchy. Some managers in developing countries, who must deal with indigenous people, will have a more difficult time making these reports.

Gilbert is also concerned about health care for consultants. As more companies downsize, they must with greater frequency bring in outside consultants and specialists for short-term work. BG has a policy that the consultant must have made prior arrangements or obtained medical insurance to be contracted.

Overlooking this policy in the press to solve a problem or get a project back on schedule means a project manager could end up facing a most expensive evacuation flight for someone who technically is not even an employee of the company. It has happened.

Norway

As mentioned, Norway has regulations covering the physical condition of workers going offshore and the medical facilities and personnel available for them there. Given the fact that most of the world's major E&P companies and contractors have operations there, the requirements are well known.

Norway's Norsk Hydro AS is a major operator there and has a sophisticated organization to meet the health needs of its employees. The company operates five fields off Norway, including the giant Oseberg complex, and will soon be adding two more.

With 40,000 employees worldwide in 49 countries, Hydro frequently dispatches specialists for upstream and downstream jobs from Norway to overseas locations often on short notice. To meet this unusual situation, it is developing a health care program for the frequent international traveler. It will be covered later in this article.

Hydro's Norwegian E&P medical department, based in Bergen, is headed by Dr. Trygve Fonneland, senior medical adviser. Fonneland, two staff physicians, and 30 nurses covering nine platforms provide for the health needs of some 1,000 workers on the platforms. Assisting onshore are three occupational nurses, a physiotherapist, and an industrial hygienist.

Offshore, Norwegian regulations require that there be a clinic on board each platform and a state-registered nurse. At the Oseberg field center, Hydro has two nurses on each shift, a total of six in the center, because of the high number of people and activity there.

The other platforms have one nurse per shift for a total of three. They work 2 weeks on-3 weeks off, then 2 weeks on-4 weeks off. This schedule permits some to live as far away as Spain.

Everyone working offshore must have knowledge of first aid. However, Fonneland says that each platform must have trained special first aiders who have completed a 40-hr advanced first aid course.

In addition, the first aid team receives 2 hr of training each offshore period. They are catering personnel and are not part of the Hydro medical department.

Fitness

Each person working offshore must have a certificate of medical fitness. The rigorous examination for this covers vision, hearing, substance abuse, motor system and mental problems, infections, diseases, and pregnancy.

There is a list of conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disorders, and diabetes, that can lead to a statement of non-compliance, making the applicant unemployable offshore.

However, Fonneland says, "If a patient comes to me and he has diabetes, I have to say no. But then he can go to the authorities and make his case, perhaps his condition is well treated; he is young, and gets the certificate."

Operators are not happy with the expense of these examinations, which must be done every 2 years, and the possible loss of employees. The workforce onshore has no special requirements about health, so why should those who go offshore be treated differently, they reason.

Evacuations

Hydro has five doctors, three of its own and two contracted from outside, available for call duty. The physician on call must always be in a location to reach a helicopter based at Bergen's Flesland airport, within 1 hr. Any of Hydro's platforms off Bergen can be reached in 30-45 min flying time.

Much farther to the north in the Haltenbanken area of the Norwegian Sea, Hydro shares three contract physicians with Statoil and Shell. They are based in Kristiansund.

If the helicopter at Bergen is tied up, another is available there. Additionally offshore, a rescue helicopter operated by Statoil is based in the Gulfaks/Statfjord field area. Finally, in a real pinch, there is a fully equipped Coast Guard medical evacuation helicopter with doctor at a base near Stavanger.

In 1996, Hydro had 95 helicopter evacuations; 154 in 1997. Data based on experience from Ekofisk show the need for one emergency evacuation each 1 million hr worked offshore. Of that, 80% is for reasons of disease, 20% from injuries.

Algeria

Whereas weather is the big danger in the North Sea, it is terrorists in Algeria. They have made assignments in Algeria among the riskiest in the oil world.

The drilling rigs there in the southern Sahara are hundreds of kilometers from anywhere. BP Amoco's Dr. Martin says she visited one that had been attacked a few weeks earlier by a gang of desert bandits.

Ominously, they had asked if there were any western expatriates on the rig. There was reason to think they would have been slaughtered if there were, she believes.

She was slated to spend the night. Realizing that she would have been the first woman to do so and that even though the Sahara is vast, arid, and barren, news travels fast there, she decided to leave before nightfall.

As a result of such dangers, evacuees are transported to Hassi Messaoud, the big oil industry supply base in the desert. From there they are flown directly to Marseilles, Southern Spain, or London. Nobody stops in the capital, Algiers.

Nevertheless, health care must continue. Paramedics from Scotland and the North Sea are flown in. They are expensive because of the frequent flights and their 5 weeks on-5 weeks off schedules.

Martin likes to work with local physicians if at all possible. They oil the wheels and know what the local setup is. Some are given advanced paramedic course to broaden their expertise.

One country that has been out of the international main stream for a long period, however, offered her a welcome surprise. She was impressed with the hospitals and quality of care in Iran after a visit there.

The remote locations of the oil world, at sea, in the jungles, on the tundra, or in the desert obviously make health care and trauma treatment far more complex and difficult than in a family practice or emergency room in London or Houston.

HECTRA

Oil & Gas Journal developed and sponsored an international conference, Health Care and Trauma at Remote Locations (HECTRA), earlier this month in Houston. Twenty-six presentations (shown in accompanying box) covered issues, medical problems, and regional challenges. Following are highlights of presentations prepared for delivery at the conference. (The box identifies affiliation and home or work base of each speaker.)

Prevention, response

Whether the industry assignments call for expatriates with or without family, rotators, or simply frequent international travelers, they should obey the ten commandments for tropical travel laid down by Dr. J.S. Keystone. Each commandment included detailed information on how to follow it.

Immunizations and vaccines were also covered. For example, he addressed the management and prevention of traveler's diarrhea and listed numerous antibiotics. He identified the health conditions that call for possible use of antibiotics before the trip starts. And Pepto Bismol made his short list as a diarrhea preventive and was rated as offering 73-75% protection.

Malaria, the scourge of the topical world and often subject of medical debate, was covered in detail. He said that no antimalarial drug regimen guarantees protection; therefore, insect precautions must be used. Fever in a returning traveler, especially within the first 2 months after return, is a medical emergency, he stressed.

In addition to common-sense measures about food and water, Keystone advised not to swim in fresh water or walk in bare feet in tropical regions.

All the advice is not about diseases, however. His tenth commandment is be wary of your conveyance. Motor vehicles are the leading cause of accidental death of long-term travelers living in the third world.

Self diagnosis

Based on experience with trekkers in Nepal who could be a 1-2 week walk from medical care, Dr. David R. Shlim used cases of diarrhea and respiratory infection to illustrate how patients can be taught to diagnosis themselves. They can then treat themselves safely and effectively with medications supplied in advance.

Trauma care

Trauma care of the severely injured patient at remote locations was covered by Dr. Bob Mark. Even in the most favorable circumstance before arrival in a hospital and in the emergency room, such care is challenging, the trauma specialist said.

In contrast, at remote locations, the paucity of resources and personnel, prolonged evacuations times, and lack of adequate facilities for definitive treatment can all make trauma care even more difficult.

He reviewed the practice of trauma care and discussed concepts and practices in modern trauma care that are especially relevant to remote area medicine.

Frequent travelers

Norsk Hydro ASA is a company with 40,000 employees worldwide. The company is also strong in consultancy services, performing project and production assistance, systematic quality, safety, and rotating machinery work, and inspections services.

These people go everywhere in the world on very short notice, according to Hydro's Dr. Roy Martin Pedersen. Some log up to 220 travel days/year to some potentially unhealthy and risky regions.

All travel, domestic and foreign, has an element of risk with regard to morbidity and stress, he said. There are health challenges for travelers. He said Hydro wants to give all employees a satisfactory working environment. A company investigation showed that expatriates were relatively well prepared by health services, but that was not the case with company travelers.

Of those making trips to the tropics or eastern Europe, some 60% who responded to a survey claimed they needed traveling advice and vaccinations; 13% didn't even think of this. Only half who went into malaria-infected regions got prophylaxis and antimosquito advice. Other problems showed up in the survey.

A result was that international travel has been put under the umbrella of health, safety, and environment, and the company has launched a program to benefit and protect frequent international travelers. He covered the challenges and issues this brings up and the steps taken to meet the goal.

Drilling rig health care

Some 5 years ago, international drilling company Sedco Forex, which operates land and offshore rigs, determined from reports from field operations that it had deficiencies in its health care system, according to Dr. Francois Pelat.

As a result, the company established a program to develop rig medical staff qualification and capabilities and set minimum equipment standards.

A traveling physician dedicated to the program took the job of developing worldwide standards for recruiting and training medical professionals and updating health and hygiene practices, and rig clinic content. An audit of the process verified compliance.

As part of the program, company rig medics are recertifed every 2 years. The rigs are audited every 2 years. Pelat said significant results have been achieved in medic qualifications and clinic standards.

A computer program, known as "Rig Medicare," has been developed in house to assist the medical staff in tracking and reporting their activities and monitoring clinic inventories.

Cooperation for health management

A group of international oil companies operating in remote locations with limited health infrastructure is looking at cooperative ways to maintain the health of its workforce and promote lasting improvements in the health of the local host community.

Drs. Ken Lindemann and Steve Simpson of Exxon International Co. and Chevron Corp., respectively, addressed the issues at the HECTRA conference.

Lindemann said there is growing recognition that the success of ventures in less-developed parts of the world is linked to the health of the host community and that cooperative responses to health concerns may have both social and economic benefits.

Members of industry must actively engage local host governments and other key stakeholders in consultation to plan for the desired outcome.

Simpson reported on local health conditions and cooperation to date in Angola, one of the hottest arenas in the oil world. He said Chevron's most important outreach program there has been the establishment of a blood bank service at Cabinda Hospital. This has dramatically reduced the transmission of blood-borne infections, most notably human immune (HIV) infections.

The major health risks for expatriates there are malaria, road and traffic accidents, beach accidents, and violent crime.

An oil industry health cooperation team has been formed in Angola. Members are Chevron, BP/Amoco, Exxon, and Texaco. He said new members are welcome.

The top four health issues identified by the group are emergency response planning, pre-employment medical issues, especially with regard to HIV and tuberculosis, malaria and vector control, and immunization guidelines.

Planning, managing health care

Dr. Melissa D. Tonn described the benefits gained by an international construction firm, M.W. Kellogg Co., with numerous expatriates in outsourcing medical services to a firm for whom she consulted. (Kellogg's parent company subsequently merged with Halliburton, which has its own engineering and construction company Brown & Root.)

She detailed the Kellogg savings when the outside medical provider performed on site services. On-site immunizations in 1997 cost some $71,000. The same immunizations at a local facility would have cost nearly $204,000 when 2-hr lost time/employee/immunization trip is factored in.

On-site drug screening that year cost $42,000 vs. $328,000 calculated for off-site screening.

She also described the benefits of location-specific, fitness-for-duty examinations done by an off-site clinic partner. The examination protocols developed by her and a company nurse markedly reduced the number of emergency evacuations, deaths, and medical assists.

Measurement of health care

Drs. Djati S. Pratignyo and Yohannes Erawan detailed the components and calculations they used in developing an essential human services index (EHSI). The index can serve as a measurement of progress in delivering essential health services at remote sites.

The essential health services package has five components for implementation at remote sites:

- Environment control.

- Occupational disease handling.

- Integrated medical evacuation system.

- Continuing critical care training.

- Epidemiological surveillance.

They have established an EHSI for ARCO Indonesia and will use it as a more objective method to measure change than subjective evaluations.

Planning for health care

The oil industry has explored or developed most of the convenient locations worldwide. Now the industry is forced to work in places that are either remote or lack any kind of infrastructure.

Health care is frequently overlooked, however, according to Dr. J. David Clyde. One can compare this, he says, to childbirth. When everything goes well, there is happiness; when a problem arises, good planning and preparation may prevent a disaster.

He analyzed the four major components that should be included in planning health care at remote sites: the business aspects of the project, the medical resources needed for the project, the assessment of the local medical resources, and the medical equipment needed at the project site.

Worldwide management

Elements of a worldwide health care management system for Schlumberger, which works in 100 countries and employs more than 60,000 people of more than 80 nationalities, were described by Dr. Alex Barbey.

He said the company has a medical network of 40 doctors and 120 medics. They treat daily medical problems and provide support and advice to management in case of emergencies and epidemics. A small group of physicians is responsible for visiting locations and assessing local health facilities.

A program, called Med-Track, follows and logs the triennial physicals of Schlumberger employees that are performed in more than 400 company-certified medical centers around the world.

Health Track is the company's intranet web site accessible to all company employees and their families. It offers information and makes recommendations on a variety of health-related matters.

Regional challenges

Three regions formerly in the Soviet Union illustrate the health risks posed by countries with attractive high potential for oil and gas exploration and production.

Randall Earl Messer of Fairweather Inc., an Anchorage, Alas., oil field medical-support operator, described in a paper prepared for delivery the establishment of a contracted medical and emergency medical evacuation service in the Russian Federation's far eastern Sakhalin Oblast. It was for an international oil consortium that recently shipped its first cargo of crude oil.

The large island is separated from the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido by the Soya Strait.

He said the island in the mid-1990s posed not only climatic threats but also a witches' brew of social, vehicular, and environmental threats to the industry staff and workers.

There were many inexperienced, intoxicated, or aggressive drivers. Other potential threats included insect and waterborne disease, exposure to blood pathogens, accidental electrocution, and perhaps unknown exposure to heavy metals or radioactive materials.

Kazakhstan

Sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, other infectious diseases, and cancer are common in the Republic of Kazakhstan (ROK), where nuclear testing was carried out in the Soviet days.

The health of the population there is declining. Life expectancy for males is 58, for females 69. Ironically, Kazakhstan has the highest number of doctors and hospital beds per capita in the world.

But it is the home to the world's deepest giant oil field, with 6-9 billion bbl of oil in place. By mid-2000, production is expected to increase to 265,000 b/d, rising to 700,000 b/d in the year 2010.

The producing company is Tengizchevroil (TCO), a joint venture of Chevron, the ROK, Mobil, and Luk Oil. Chevron holds 45% of the venture.

Tengizchevroil has two medical directors, Drs. Philip Sharples and Alipio Carvalho. They prepared a paper detailing geographic, social, and health conditions in the ROK and the delivery of health care to 3,000 TCO employees and 7,000 contractors by TCO.

The hospital at Tengiz on the eastern side of the Caspian Sea provides emergency, primary, and secondary medical care. The hospital has 12 in-patient beds and outpatient clinic, including occupational health, X-ray, laboratory, pharmacy, intensive care, and trauma room.

TCO has a medical staff of 57 persons with half on duty each rotation. There are 5 Chevron employees and 52 Kazakh nationals, 11 of the latter being physicians.

Sharples and Carvalho are back-to-back medical directors. Sharples' home is in England; Carvalho's is in Portugal. At the start-end of their rotations, they meet in Budapest for a 2-hr session. As a result, electronic mail (e-mail) is a prime means of communications.

Kosovo

Dr. Robert Conte described how Halliburton's ongoing contracts to support the US military around the world through its Brown & Root Services created the need for medical support of its expatriates.

This experience is transferable to medical support for Halliburton's energy services group at remote locations worldwide, he said.

Telemedicine

Dr. Oscar Boultinghouse reported that the US oil industry is second only to the US military in having personnel in remote locations. The high cost of medical evacuations is therefore a driving force for development of remote telemedicine. He defines that as immediate, on-demand access to emergency medical evaluation using high-resolution, real-time interactive video.

He reviewed data for all Gulf of Mexico medical air evacuations from oil industry operations arriving at the University of Texas Medical Branch Emergency Center in Galveston. Of the 200 airlifts, he found that 39% were discharged with no significant interventional care. Many of these, he said, could have been cared for on the rig or vessel using video conferencing.

NASA

Dr. Muriel Ross of the U.S, National Aeronautics & Space Administration described a telemedicine system that uses three-dimensional (3D) medical images being developed by the space agency.

"We are looking at methods to bring the clinic to the patient rather than the patient to the clinic. This will prepare us to use the technology for spacecraft crews traveling to the international space station, Mars, or other planets," she said.

Hibernia

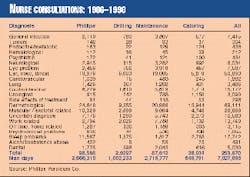

The Hibernia oil production platform is in an extraordinarily hostile part of the North Atlantic. Poor weather conditions create a challenge for flying operations to the platform some 300 km southeast of St. John's, Newf. This can cause delays (Fig. 1) in medical evacuations that can convert a minor medical problem into a major emergency, according to Dr. Carl Robbins.

As a result, since 1997 when the platform was floated out, the platform health service has relied in part on telemedicine. This means, he said, that a nurse onboard the platform has the capability of a communications link with a physician onshore.

The link permits communication via high-resolution photographic images and diagnostic peripherals. Images are captured using specific software and sent as e-mail attachments for review by a physician onshore.

He outlined the rate and type of illness and injury events that occur and the support provided by telemedicine. He said the expectations for telemedicine applications generally tend to exceed what can be accomplished. He identified the limitations and the advances required for further development of this technology in remote environments.

Safe food, water, and medicine

Remote-site catering is the most important element in a remote project. Without access to safe water and food, nothing happens. Yet some operators do not recognize this, according to Christophe Parent. He said the remote site caterer must respect the rules concerning food hygiene and safety, safe working practices, equipment maintenance, and personal hygiene.

Yet when a client faces restricted budgets or increased manpower, he may try to solve his difficulties by pushing the service provider to cut corners. The client may not realize how important ethnic "home cooking" is in maintaining worker morale and productivity in a foreign setting. More serious is the increased chance that sanitary standards may be compromised.

Medicines

Providing safe medication at proper doses with adequate information to an employee working at a remote site is much more difficult than in a developed country. There, cooperation between medical professionals helps maintain standards of treatment. But at a remote site, the medic must often fill these roles, serving as physician, nurse, and pharmacist.

Brian Wells, a pharmacist, whose PhD thesis was "Medicines on Offshore Installations," detailed the medical management necessary to ensure safe and effective medication at remote sites. His firm has supplied work sites in such countries as Tajikistan, Angola, and Yemen with pharmaceuticals.

Psychological, social aspects

Psychological readiness for a foreign or remote assignment is just as important as physical readiness. If problems in either lead to repatriation, the direct and indirect costs are high.

The psychological screening of candidates (and "trailing spouses" and dependents, in some cases) for such jobs is therefore crucial for anyone charged with selecting expatriates, says Dr. Charles West. He is a psychologist and has worked in corporate settings as a clinician, administrator, and consultant.

Such screenings pose difficulties in the US where medical screening of candidates usually precludes an opportunity to confirm or refute a candidate's self report about psychiatric or substance-abuse history. Also, the 1991 Americans with Disabilities Act makes clear that decisions based on medical factors alone can be viewed as discriminatory.

As an alternative, West described a screening process that employs self assessment by the candidate (and spouse, if relevant).

West covered the entire foreign experience from the negative reputation such assignments have if the company has no re-entry plan, in-country support, the interruption of spouse's career, and his or her loss of identity.

Repatriation.

Repatriation is often the most difficult phase because expats do not anticipate its stresses and challenges. They are assuming they are returning home, but where is "home" after a year or two in an alien culture?

If the transition is difficult, the returning expat may target the company as the source of the problem. West said that current statistics show that 25% of employees leave their company within 1 year of return.

Crisis help

Statoil's Dr. Arne Ulven in a presentation prepared for HECTRA dealt with another aspect of foreign assignments that gets little notice: the death or serious injury or illness of an expat while overseas or of a family member back home.

Statoil has set up a formal team to render support and help in such cases.

Mosquitoes, other disease vectors

The transmission of diseases by insects and rodents continues to causes significant illness and death worldwide-a resurgence of old foes, according to Dr. Robert Shaw.

Because of the reduction of use of insecticides in many areas as a result of environmental concerns, mosquitoes have reappeared in many areas where they were once eradicated.

Accompanying mosquitoes' return have been major outbreaks of Dengue fever in the Caribbean, South America, and the Pacific Rim, areas previously free of the disease.

Remote-site operations expose personnel to insect and rodent vectors and could promote the re-emergence of other important vector-borne diseases that are waiting to reappear in humans as exploration goes to distant locales.

Shaw detailed the steps managers at remote sites should take to lessen the chance this will happen.

Malaria in Cameroon

Dr. Jean-Marie Moreau reviewed data collected and measures taken to control malaria while line-of-sight and right-of-way surveys were conducted along a 1,000-km pipeline route through central Cameroon.

A presurvey health-risk assessment determined that malaria presented one of the greatest operating challenges for land-based activities. Malaria is responsible for about 20% of all deaths among Cameroonians between the ages of 15 and 44.

Most of the some 160 workers on the survey crew working in four rolling camps were Cameroonian nationals who came from nearby villages. They worked as brush cutters.

Moreau reports that implementation of malaria control, reducing mosquito contact, and providing ready access to diagnosis and treatment reduced productivity loss among the immune personnel. If personnel seek prompt diagnosis and treatment, there should be no deaths, he says.

New Guinea malaria

Dr. Andrew Frean of BP Amoco Asia-Pacific described how BP managed the risk of malaria during the development of the Hides gas field in the remote southern highlands of Papua, New Guinea.

He reported that in 1991-1996 more than 1,000 BP employees were treated for malaria. Another serious problem was the increase of Falciparum malaria to chloroquine, a malaria preventive. Control proved difficult despite vector control, personal protection, chemo-prophylaxis, and on-site treatment and diagnostic capability.

Working with a World Health Organization malaria consultant, BP's medical unit decided to abandon the previous "fortress" approach and go to a community-based control program. Improved diagnosis and treatment and spraying of community houses and buildings with insecticide caused a dramatic reduction in malaria incidence.

Frean said malaria transmission has virtually ceased, thereby reducing to virtually zero the risk of contracting malaria in the areas.

Speakers and their HECTRA subjects

Prevention and Response

The Ten Commandments of Tropical Travel, Dr. Jay Keystone, professor of medicine, University of Toronto, and staff physician, Travel & Tropical Disease Centre, Toronto Hospital.

Emergency Self Diagnosis and Self Treatment, Dr. David R. Shlim, Shoreland Inc., Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Advanced Trauma Care by Paramedics Working at Remote Sites Alone, Dr. Bob Mark, medical director, Frontier Medical Services, Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire, UK, and associate specialist, Royal Bradford Infirmary

Health Challenges for Frequent International Travelers, Dr. Roy Martin Pedersen, medical officer, Norsk Hydro ASA, Porsgrunn, Norway

First Aid, Health Risk Assessment, and Resources for Offshore Rigs

Developing Drilling Rig First Aid and Medical Resources, Dr. Francois Pelat, Sedco Forex Schlumberger. Montrouge, France

Assessing the Drilling Rig for Health Risks, R.A. Hanson, senior occupational health adviser, BG plc, Reading, UK

Strategic Cooperation for Health Management in Remote Host Communities

Systematic Cooperative Planning Throughout the Project life Cycle to Maintain the Health of the Workforce and Promote Lasting Improvement in the Health of the Local Host Community, Dr. Ken Lindemann, assistant medical director, Exxon Co. International, Florham Park, NJ

Developing a Model for Strategic Management in Angola, Dr. Steve R. Simpson, regional medical director-Africa, Chevron Corp., Luanda, Angola

Planning/Managing/Monitoring Health Care

The Case for Outsourcing Medical Services at a Major, International Engineering and Construction Company, Dr. Melissa Tonn, medical director, Presbyterian Occupational Health Network, Dallas

Measurement of Progress in Delivering Essential Health Services at Remote Sites, Dr. Djati S. Pratignyo, ARCO Indonesia, Jakarta

Planning and Developing Health Care at Remote Sites, J. David Clyde, medical director, ARCO International Oil & Gas Co., Plano, Tex.

Worldwide Management of Health Care in Remote Locations, Dr. Alexander Barbey, international health coordinator, Schlumberger, Montrouge, France

Regional Challenges and Solutions

Kazakhstan-Health Care Delivery for Tengizchevroil, Dr. Alipio Carvalho and Dr. Phillip Sharples (speaker), medical directors, Tengizchevroil, Tengiz, Kazakhstan

Russia-Development of a U.S. Emergency Medical Service in the Sakhalin Oblast, Randall Earl Messer, Fairweather Inc., Anchorage, Alas.

Azerbaijan-Health Care Challenges for the Oil & Gas Industry in the Caspian Region, Dr. Will Ponsonby, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Telemedicine

Telemedicine and the Hibernia Platform off Newfoundland, Dr. Carl Robbins, chair of telemedicine, Health Sciences Centre, St. John's, Newf

Emergency Telemedicine Services, Dr. Oscar Boultinghouse, assistant professor emergency medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Tex.

Safe Food, Water and Medicine

Awareness, Dedication, Expertise Essential for Clean Food and Safe Water, Christoff Parent, vice-president, Sodexho Remote Sites, Paris

Providing Medicines for Remote Locations, Brian Wells, PhD, Pharmaceutical Consultant, Wells Offshore, Withersea, East Yorkshire, UK

Psychological and Social Aspects of Remote Assignments

Psychosocial Issues with International Assignees and their Families; In-Country Support and Repatriation, Charles West, PhD, program manager and clinical director, International Employee Assistance Program, AEA/SOS International, Newton, Mass.

A Program to Support Expatriates and Next of Kin at Home and Abroad During Severe Personal Events, Dr. Arne Ulven, senior occupational physician, Statoil AS, Bergen, Norway

Mosquitos and Other Disease Vectors

Vector-Borne Diseases; The Resurgence of Old Foes, Dr. Robert Shaw, chief medical officer, Texaco Inc., White Plains, NY

Malaria in Cameroon-Support for a Pipeline Survey Crew, Dr. Jean-Marie Moreau, Exxon Co., International, Florham Park, NJ

Managing Health Risks During Development of a Gas Field in Papua New Guinea, Dr. Andrew Frean, BP Amoco Asia-Pacific, Hong Kong

Medical responsibilities

The occupational health department should:

- Audit and obtain comprehensive information about the quality and location of local medical support and advise on the appointment of a local medical advisor.

- Undertake a medical risk assessment in order to enable prospective expatriates to reach an informed decision whether or not to accept their assignments.

- Categorize the location as " Staff Only," "Staff and Partners," or "Staff, Families, and Children."

- Maintain up-to-date, location-specific information to give staff prior to relocation.

- Perform appropriate pre-assignment medicals on staff and dependents and provide immunizations, advice, and materials to reduce the risk to health while on assignment.

- Ensure that the organization contracted to provide medical advice to overseas locations on a 24 hr basis can and does deliver the service.

- Ensure that the organization contracted to provide emergency medical support, including repatriation can and does deliver the service.

- Undertake periodic medical examinations of expatriates and their dependants during their overseas assignment.

- Undertake post-assignment medical examinations.

The human resources department should:

- Ensure that arrangements are made early for expatriates and dependants to attend a pre-assignment medical examination and advice at headquarters.

- Ensure that the assignee and management are aware of any constraints regarding accompanying dependants that may apply to the assignees' location.

- Ensure that expatriates and relevant dependants are aware that they are required to make themselves available for periodic medical examination at appropriate intervals in the course of the assignment.

- Ensure that expatriates are aware of the requirement to keep their local management informed in general terms and the OHD aware in specific terms of any specific illness or injury that they or accompanying dependants may suffer in the course of the assignment.

- Ensure that expatriates are aware of the location of specific constraints regarding the use of local facilities for elective medical, surgical, or obstetric services.

- Ensure that expatriates are fully aware of the expense and accommodation implications if they or a member of their family are repatriated for medical treatment.

The local line management should:

- Facilitate an initial OHD audit of the location, and periodic reviews, to enable the OHD to make appropriate recommendations.

- Ensure that they have OHD recommendations regarding specific health risks in the location.

- Ensure that they have OHD recommendations concerning local medical facilities and staff and preferably have an OHD recommended local medical adviser.

- Confirm that they accept the OHD recommendations or provide explanations for their rejection.

- Make sure all staff, dependants and new arrivals and their management successors are aware of these recommendations.

- Ensure that they and their staff are aware of the role of the contracted medical assistance provider and the means of accessing assistance.

- Ensure that the OHD and the assistance provider are made aware of any significant medical problems early.

- Ensure that their expatriate employees are aware that they have a duty to behave in a safe, responsible manner while on assignment.

Expatriates should:

- Liaise with HR and OHD to arrange pre-employment medical examinations for themselves and accompanying dependants well in advance of their travel date

- Discuss any local risks and any concerns that they may have with the OHD staff.

- Ensure that they are aware of the recommendations regarding local medical services, and if applicable meet with the local approved medical advisor on arrival.

- Ensure that they are aware of the arrangements for emergency medical support, contact numbers, etc.

- Ensure that line management are aware in general terms and the OHD in specific terms of any significant illness or injury.

- Ensure that they and their dependants make themselves available at appropriate intervals, during home leaves, for periodic medical examinations at the OHD. There can be a degree of flexibility in the timing of these and with good communication and common sense the dates can be adjusted to avoid any inconvenience.