Despite recent gains in momentum, prospects for the Baku-Ceyhan Caspian oil export line remain doubtful

Despite recent gains in momentum, prospects for the Baku-Ceyhan Caspian oil export line remain doubtful

The proposed Baku-Ceyhan pipe-line-one of several options being considered as the main export route for oil from the Caspian Sea region-has had many opponents and few proponents. The pipeline would ship oil from the Azeri sector of the Caspian to the port of Ceyhan on the Turkish Mediterranean coast.

In October, unconfirmed press reports stated that BP Amoco PLC had announced it would back the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, after opposing it consistently since 1995 (OGJ, Oct. 25, 1999, Newsletter). This development has sparked excitement and new optimism among the interested political parties, including the US.

BP Amoco's announcement not-withstanding, the fundamentals of the Baku-Ceyhan dispute have not changed, and there is no guarantee that the project will materialize. There is, however, a guarded optimism on the part of the interested political parties that a breakthrough may be in the offing.

From the point of view of the Azerbaijan International Operating Co. (AIOC) consortium-the upstream group developing three of Azerbaijan's key Caspian Sea fields-the decision has at least provided valuable time for it to better weigh its options.

Whether the breakthrough will cause AIOC to cancel its plans to triple the capacity of the existing Baku-Supsa export route as an interim transport option is uncertain. If this option remains on the table, and if the region's countries do not obtain an iron-clad commitment from AIOC regarding Baku-Ceyhan, the Ceyhan export route may never materialize.

Debate's beginning

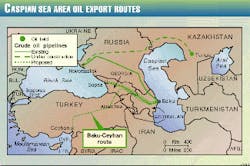

Although it dates back to 1995, the controversy over the proposed Baku-Ceyhan pipeline heated up in July 1997, when AIOC announced it had narrowed to three the route options for the main export pipeline (MEP) from the Caspian Sea area (see map, p. 23). The three options are: an expanded version of the Baku-Novorossiisk route to Russia (the northern route), an expanded version of the Baku-Supsa route to Georgia (the western route), and a new route from Baku to Ceyhan via Georgia (the Mediterranean route).

After start of production from AIOC's Chirag field in the Azeri sector of the Caspian Sea in November 1997, the first two routes were used to transport early oil production (the earliest exports were by rail). The two routes have a combined capacity of 200,000 b/d.

The Novorossiisk route, an old Russian pipeline that was refurbished and restarted in the fall of 1998, is currently shut down as a result of the armed conflict north of the Caucasus, although Russia has offered to build a detour around the war zone (see story, p. 25). The Supsa route replaced another derelict line and was commissioned at the end of 1998. AIOC's current production is about 110,000 b/d, handled through the Supsa route.

AIOC, led by BP Amoco, with a 34% share, is a consortium of 10 international oil companies plus the State Oil Co. of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR). It was created in late 1994 under a 30-year production-sharing agreement (PSA) to develop the Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag fields complex in the Azeri sector of the Caspian Sea. The fields' reserves are estimated at 4 billion bbl of low-sulfur, 35° gravity crude.

AIOC was initially expected to announce its chosen MEP route by fall of last year but has repeatedly postponed the decision. BP Amoco's October announcement came closest to publicly endorsing an MEP.

From the start, the choice of MEP route has been controversial. Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, with strong backing from the US, have openly supported the Baku-Ceyhan route, while AIOC has shied away from backing this route. In the meantime, BP Amoco-operator of AIOC-has made low-key overtures toward Iran regarding an unofficial fourth option (a southern route), according to a BP Amoco official speaking at the Offshore Technology Conference in Houston last May.

Negotiations are under way between AIOC and the region's national governments to reach a final decision on the MEP.

Pros and cons

The advantages of the Baku-Ceyhan option are that it would: provide a secure route for export of Caspian Sea oil westward, avoid tanker traffic through the heavily congested Bosporus Strait, help integrate the economies of Turkey and the Caspian nations (including Georgia), and strengthen the independence, sovereignty, and prosperity of these new nations. At the same time, it could mitigate and help resolve ethnic conflicts in the region, including the one between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh.

These attractions are consistent with the US's geopolitical objectives in the region, which explains US support for the Baku-Ceyhan route.

The opposition to Baku-Ceyhan has come solely from AIOC and is based on concerns over shipment volumes and construction costs. AIOC has said that reserves in Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag-about 4 billion bbl-are sufficient to feed an 800,000 b/d pipeline but that a minimum of 1 million b/d of throughput is needed to make Baku-Ceyhan economically viable. Subsequently, the group asserted that reserves of 6 billion bbl (presumably corresponding to 1.2 million b/d of pipeline capacity) are needed to make Baku-Ceyhan viable.

According to press reports from Turkey, that country no longer sees volume as an issue for the pipeline. The reason for the apparent discrepancy between the Turkish and AIOC viewpoints is not known, although Turkey may be counting on additional oil supplies from Kazakhstan.

In the negotiations so far, neither side seems to have taken into account-at least as can be judged from press reports-the potential implications of BP Amoco's recent gas-condensate discovery in Azeri waters, Shah Deniz, which will be discussed later.

Another point of confusion regarding production volumes is whether AIOC's 4 billion bbl figure refers to proven or proven plus probable reserves. If it refers to proven reserves, AIOC is arguably conservative in its estimate of ultimate recovery from Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag, because field reserves tend to grow with time, and long-term development planning is commonly based on proven plus probable reserves.

In terms of cost, AIOC has maintained, with some justification, that Baku-Ceyhan is the costliest of the three MEP options, with Baku-Supsa being the least expensive. AIOC has put a price tag of $3.7 billion on Baku-Ceyhan, vs. an estimate of $2.4 billion by Botas, the Turkish pipeline company that has been nominated to build the pipeline. Turkey claims the $3.7 billion figure is based on labor costs in the west and ignores the lower labor costs in the Caspian Sea region.

As the negotiations were heading for a deadlock, the US let it be known in September that it was somewhat frustrated over the slow pace of talks and that it considered the "ball to be squarely on AIOC's court" (Financial Times, Sept. 21, 1999). AIOC promptly rejected this assertion.

US position criticized

The US's lobbying efforts in the Caspian pipeline debate have been criticized by some-including this journal-as an unnecessary intervention or an intrusion (OGJ, Sept. 27, 1999, p. 23). The critics argue that the decision on Baku-Ceyhan should be left entirely to the investors; i.e., AIOC.

Such criticism is poorly justified. Firstly, it overlooks the fact that oil and politics, at least in that part of the world, are intricately linked. This is a political reality that cannot be denied.

It has long been a US policy to view oil as an instrument of geopolitical interests and vice-versa. The Persian Gulf War was a case in point, and a strong one. So, there is nothing unusual in the US's stance on Baku-Ceyhan. And, considering the political objectives behind such policy, the US can hardly be taken to task for its lobbying in favor of Baku-Ceyhan. Besides, the US government has clarified that it sees its role in the dispute as a facilitator and that it does not expect private oil companies to make investments that are not economical.

Secondly, criticism of the US overlooks the larger dimensions of investment decisions: in this case, safety and the environment. Although, in principle, no one can deny a business venture such as AIOC the right to make investment decisions without interference from the outside and the right to minimize costs in order to improve profits, equally, no business venture can afford to ignore safety and environmental risks in its decision. The benefits of cost reduction should be weighed against the potential risks involved. In this context, that means the risk related to increased Bosporus traffic becomes relevant.

The Bosporus factor

For Turkey, keeping the Marmara Straits-in particular, the Bosporus-free of heavy tanker traffic has been an overriding concern in the MEP dispute. For oil to reach western markets, both the Supsa and Novorossiisk routes rely on tanker passage through the Bos- porus. Turkey, therefore, has consistently opposed these routes.

A tanker accident in the Bosporus poses a safety and environmental risk of major proportions in this historic, heavily populated area. To underline the importance of its concerns, Tur- key's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ismail Cem, stated last June that it is the safety of the Marmara Straits, rather than oil supply or commercial considerations, that drives Turkey's lobbying for Baku-Ceyhan. The financial incentives Turkey has given to AIOC (to be detailed later)-amounting, in effect, to a financial sacrifice-support this position.

On the Bosporus issue, Turkey's bargaining position has been weakened by a lack of negative publicity on the risks to safety and the environment. Recalling the public furor generated in Western Europe when Royal Dutch/ Shell unveiled its plans to dump the Brent spar in the Atlantic (notwithstanding Shell's assurances that the disposal would pose minimal environmental risk), there has been no media blitz or a Greenpeace-type organized movement in Turkey focusing on the risks posed by increased tanker traffic through the Bosporus.

Without passing judgment on Greenpeace's tactics (the organization subsequently apologized to Shell for being misinformed), one wonders how AIOC's position on Baku-Ceyhan would have been affected if there had been intense negative publicity on these risks, or if there were a greater awareness in the Turkish public mind of the Exxon-Valdez disaster off the Alaskan coast a little over a decade ago.

In all, it would not be inaccurate to say that Turkey has not used the "Bosporus card" effectively.

Turkey's real Achilles heel on the Bosporus issue is the 1936 Montreux Convention. By this convention, Tur- key is bound to let commercial ships pass through the Bosporus. Legal experts point out, however, that Turkey can legitimately take steps that would reduce tanker traffic in the Bosporus or insist on high-liability insurance that would render tanker transit through this passageway rather expensive.

New developments

Two recent developments have substantially affected the Baku-Ceyhan equation. One of these was Ankara's offer last June of a financial guarantee to AIOC to cover the difference between AIOC's $3.7 billion cost estimate for Baku-Ceyhan and Botas's $2.4 billion estimate. The financial guarantee would be contingent on Botas being designated main construction contractor.

This offer was aimed at alleviating or removing AIOC's cost concerns. It was not, however, sufficient for AIOC to drop its objections to Baku-Ceyhan.

AIOC subsequently said it wanted the Turkish government: to provide third-party risk coverage for the Azeri and Georgian sections of the line; to assume cost overruns due to construction delay, regardless of cause; and to grant it the right to withdraw from the project at a later date if AIOC determines that the project is not economically viable.

Requests of this type are rather unusual in the industry.

The Turkish government has been sympathetic to some of these requests but unreceptive to others.

The other new development was BP Amoco's Shah Deniz gas-condensate discovery in the Azeri waters in the Caspian. BP Amoco is operator of Shah Deniz on behalf of a group of seven companies.

The discovery well encountered 220 m of net pay in three zones, the deepest of which flowed 50 MMcfd of gas and 2,965 b/d of condensate on test, constrained by equipment capacity (OGJ, July 19, 1999, p. 35). Initial estimates-obviously somewhat speculative-place gas reserves at 15-25 tcf. In any case, well deliverability seems impressive, and the discovery will almost certainly prove commercial.

Condensate from Shah Deniz could be added to the Baku-Ceyhan oil stream to mitigate the volume problem while at the same time enhancing the quality of the crude. The gas column in Shah Deniz field may also be underlain by an oil rim, in which case the impact on Baku-Ceyhan could be enormous.

An appraisal well was spudded, but it apparently ran into technical difficulties; further appraisal drilling is planned.

Behind the scenes

While the Baku-Ceyhan negotiations have been closed to the public, it is possible to glean from press reports, etc., what may have transpired behind the scenes before BP Amoco's October announcement of its support for the Baku-Ceyhan option.

With the costlier and now strife-stricken Novorossiisk route all but eliminated as an option, AIOC left little doubt that it preferred Baku-Supsa as the MEP. In a press conference in September, AIOC chief David Woodward stated that Supsa might be incorporated into the MEP. This position was consistent with AIOC's announcement in early 1997 that the Supsa route was its preferred MEP. In the same press conference, Woodward also threatened to delay further investment on Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag if the dispute over the MEP were not resolved. This was an ominous sign; Or was it a bluff?

To underline its preference for Baku-Supsa, AIOC in September announced plans to triple the capacity of this line to 300,000 b/d by laying a parallel line and to boost production commensurately by 2002. It is not known if such an expansion was in AIOC's original plans. If it was, it begs the question, Why did AIOC not build a larger-capacity Baku-Supsa line when it replaced the old Russian line at a cost of nearly $600 million in 1998?

If the expansion plans are new, they do not bode well for Baku-Ceyhan, at least for the near future. The expansion could be the first step toward raising the status of Baku-Supsa to MEP. Even if Baku-Supsa does not reach the status of MEP and remains at its tripled capacity, the Iran route, if it becomes available, could serve as an ancillary export conduit to Baku-Supsa.

In any event, a triple-capacity Supsa route would weaken the argument for building Baku-Ceyhan in the near future. It would also give AIOC time to explore the Iran option. The expansion plans therefore could be a shrewd move on the part of AIOC.

In return for agreeing-albeit reluctantly-to a limited expansion of Baku-Supsa, the Azeri and Turkish sides wanted AIOC to commit to Baku-Ceyhan at a later date. AIOC has been unwilling to make such a commitment, arguing that it is still short of the requisite 6 billion bbl of reserves and that it needs more clarifications on financial issues.

If it were satisfied with the financial guarantees, the reason AIOC would still see volume as an obstacle to Baku-Ceyhan is difficult to understand. Given Turkey's financial guarantees, AIOC could arguably live with a pipeline capacity of less than 1 million b/d to be met by reserves of 4 billion bbl.

Parallel to these developments, AIOC also announced that it expects peak production rates from Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag to be reached in 2007, 2 years later than originally thought. This could afford a convenient delay for AIOC if it were to keep its options on Baku-Ceyhan open, eyeing the southern route as a backup.

In all these developments, Turkey has risked an unpleasant prospect. In 1995, Turkey lobbied actively for a 100,000 b/d Supsa line to transport early oil, under the expectation that a limited Baku-Supsa would be a precursor to the main Ceyhan route. It was even willing to finance the Supsa line. Now, it is facing the possibility that Baku-Supsa will become the MEP, obviating the need for Baku-Ceyhan.

Smoke or substance

When Reuters reported that BP Amoco would back Baku-Ceyhan, the news was met with excitement in Azerbaijan and Turkey. The US also expressed its pleasure.

The reasons behind BP Amoco's apparent turnabout are not difficult to surmise. First, with the talks nearing a deadlock, and with Azerbaijan, Turkey, and the US still firmly opposing the Supsa route, BP Amoco realized that AIOC was facing an uphill battle. With Turkey's offer of financial guarantees (although not totally satisfactory), AIOC had lost the edge in its opposition to Baku-Ceyhan on financial grounds.

AIOC's sense of isolation was probably heightened by Turkey's announcement last month that it was determined to have Baku-Ceyhan constructed with or without AIOC's involvement. (About the same time, the US invited Russia to join the Baku-Ceyhan project, although the invitation had only a symbolic effect, because Russia still favors the Novorossiisk route.) BP Amoco may have wondered whether AIOC was not overplaying its hand.

BP Amoco must have also concluded that the chances of the US easing or lifting its sanctions against Iran in the foreseeable future were remote, putting the southern route in indefinite limbo, and that it could not realistically expect smooth sailing of its planned merger with ARCO from a sulking US administration.

A much more compelling driver behind BP Amoco's decision, however, was probably the Shah Deniz discovery. Shah Deniz, with its condensate (and possibly oil) reserves, not only alleviated AIOC's volume concerns regarding Baku-Ceyhan, but, more significantly, it opened up the potential for gas exports from Azerbaijan. Turkey is the logical recipient country of Azeri gas, and BP Amoco felt it could not afford to further alienate Azerbaijan and Turkey. (A year ago, BP Amoco's products were nearly boycotted in Turkey).

Although BP Amoco's backing of Baku-Ceyhan created a new optimism among Caspian region countries that the project would come to fruition, there is no guarantee that this will happen. The announcement does not commit BP Amoco to Baku-Ceyhan; it only notes that the company views Baku-Ceyhan as a "strategic" route, and that it would take a lead role in obtaining financing for the project, together with governments and financial institutions. The economic viability of the project appears still to be an issue.

The announcement did not address AIOC's volume concerns, the role of a triple-capacity Baku-Supsa, and the throughput and timing of Baku-Ceyhan. There is also the question of whether other AIOC members would go along with BP Amoco's decision. Financing, too, remains an issue.

The immediate fallout from BP Amoco's announcement was confusion. Two days after it was made, Reuters reported that President Heydar Aliyev of Azerbaijan said he had received written confirmation from John Browne, BP Amoco's CEO, that BP Amoco would guarantee cost overruns for the Azeri and Georgian sections of the pipeline to Turkey. BP Amoco promptly issued a denial, adding that there had been a "misunderstanding."

Assuming that it was sincere, and not a ploy to gain more time, BP Amoco's announcement should be viewed more as a potentially important step towards Baku-Ceyhan than a breakthrough in negotiations.

Missing debate

Beyond the foregoing imponderables, further public discussion of what lies ahead in the Baku-Ceyhan saga is virtually useless. This is because there is little subsurface technical data in the public domain that affects these pipeline decisions.

Field development plans, reserve estimates, production forecasts, production performance data, etc., are technical aspects that play a paramount role in determining pipeline timing and capacity. Yet a discussion of these aspects and their impact on pipeline decisions has been singularly missing in policy debates surrounding Baku-Ceyhan.

This is not surprising, considering that such technical aspects lie outside the spheres of interest of the economists, politicians, and public policy-makers that have, for the most part, addressed the pipeline issues to date. There is little doubt that if the requisite technical data had been available in the public domain, there would have been greater consensus on the merits of Baku-Ceyhan among the disputants.

Presumably, the shareholders' technical experts discuss these technical aspects in detail, but whether they bring their deliberations to weigh fully in the negotiations is doubtful. As a matter of prudent field practice, the pace of field development should not be used as an instrument to promote a particular pipeline choice. The volume and capacity questions will gain clarity in the light of appraisal results (including the condensate-gas ratio) from Shah Deniz.

Looking beyond

Even in the worst-case scenario, in terms of volume, if reserves from Azeri-Guneshli-Chirag plus Shah Deniz prove insufficient to economically justify Baku-Ceyhan, there is plenty of Kazakh and Turkmen oil to make up the shortfall. In fact, in the recent past, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and the US have expressed interest in having Kazakh oil contribute to Baku-Ceyhan, increasing its throughput to as much as 2 million b/d. Kazakhstan has viewed such a possibility favorably.

The recent US invitation to Russia to join the Baku-Ceyhan project was a political boost in this direction, further encouraging Kazakh participation. To take advantage of such opportunities, AIOC could form new commercial alliances across the Caspian-a development that would be in the interests of all the countries in the region, as well as the US.

All indications are that AIOC has not attempted to form such alliances. In an apparent show of greater flexibility, AIOC last month approached producers on the other side of the Caspian to inquire how much oil they could contribute to Baku-Ceyhan, according to a Financial Times report. It is too early to speculate whether these inquiries will lead to a substantive change, but the move could bring Baku-Ceyhan one step closer to reality, and in a relatively short time.

The political entities are hoping to sign agreements on Baku-Ceyhan at the meeting of the Organization for Security & Cooperation in Europe in Istanbul on Nov. 18 and 19. How these agreements will affect the final fate of the project remains to be seen. It will be interesting, however, to watch the Baku-Ceyhan saga played out in the coming weeks and months.

The Author

Ferruh Demirmen is a consultant and lecturer in petroleum geology, field development, reserves estimation, and appraisal strategy and economics in Houston. Prior to moving to Houston, Demirmen worked in many parts of the world and held various positions, mainly with Royal Dutch/Shell, over a span of 30 years. He holds a PhD in geology from Stanford University.