One company's system for finding best pipe, coating suppliers

Since late 1997, the natural gas transmission unit of TransCanada PipeLines Ltd., Calgary, has employed a system for identifying, in terms of the company's specific needs and criteria, the best suppliers of line pipe and pipe coatings.

Among other results, the Supplier Performance Measurement Process (SPMP) has resulted in a total purchase-price cost reduction of up to 6% on some of the more recent TransCanada line pipe and pipe coatings orders.

The steps in the process with examples are explained here.

Merger

TransCanada, created in 1998 in a merger between TransCanada Pipelines and NOVA Gas Transmission, uses a $26 billion asset base to provide energy services to North American and international markets.

TransCanada Transmission owns and operates more than 36,000 km of natural gas gathering and transmission pipelines throughout Canada and the US. Pipe diameters vary from 114.3 mm (4 in.) to 1,219 mm (48 in.) and cover a range of pipe grades up to and including CSA Gr. 550/API X80.

Its pipeline system carries about 18% of all the gas produced annually in North America. During 1998, this system transported 4.7 tcf, or more that 80% of marketed Canadian production.

TransCanada's energy business is healthy and profitable; however, heightened competition and economic deregulation requires that TransCanada rethink its business strategies and develop new services to benefit customers and shareholders.

In the case of the pipeline services business, some initial changes resulted in an accord being struck with the Canadian gas-producing community. This accord uses competition, collaboration, and negotiation, rather than regulation, to provide the industry with the following benefits:

- The ability for participants to earn increased revenues and benefit from decreased costs.

- An acknowledgment of the need to construct competitive incremental pipeline capacity by both new and existing pipeline companies.

- An acceptance of the need for regulatory changes that will provide existing and new pipeline companies with an equal opportunity to compete.

For instance, within the Alberta transmission system, the old single charge "postage stamp" price was replaced with a new pricing structure supporting the principles of the accord: Customers with shorter transportation requirements pay less than those longer distances from their designated market place.

The intention is that these new tolling charges better reflect transportation costs and thereby make our customers and TransCanada Transmission more competitive.

Over the last decade or so, both the original NOVA and TransCanada Pipelines placed a great deal of focus on the development of procurement strategies and leveraging purchasing power with their "traditional" suppliers of line pipe and pipe coatings.

The goals were obviously to optimize quality and technical compliance and to provide lowest life cycle costs within the construction and maintenance programs. The effectiveness of these programs, however, had never been systematically and objectively evaluated.

While building upon previous technical and quality work,1 the SPMP was the first model specifically developed to measure suppliers simultaneously in quality and technical and commercial performance.

Cost reduction

In industry, it is essential for businesses to strive to get a handle on cost and reduce or avoid it. The common approach, by businesses measuring suppliers' performance, is either to measure every element that is a cost contributor or to only measure specific areas such as technical compliance.

This practice in itself is wasteful of resources and ultimately not cost effective since it measures items that are too specific or only marginally influence the overall cost of poor performance. A review by TransCanada concluded that there are some basic rules that should apply when selecting items to measure:

- Have the stakeholders (the users of the commodity) select the technical and service elements to be measured.

- Do not attempt to measure everything; select a manageable number of elements.

- Use historical supplier performance as the indicator for what is critical to measure.

- Test the elements selected to ensure that they are critical to the successful application of the commodity or service; e.g., "If this commodity is delivered late, what are the consequences arising from construction delays and interrupted customer service?"

The purpose of the SPMP was to allow for the measurement and monitoring of suppliers' performance by monitoring and observing key commercial, technical, and qualitative aspects and recording specific measurement. These data were then analyzed and the performance status of the suppliers determined.

It is not the intent of the program to provide a "pass" or "fail" rating but rather to supply an objective industry comparison while providing recommendations for improvement both for the suppliers and of the program within TransCanada.

In turn, this removes the reliance on an individual buyer's knowledge and establishes total installed and in-service costs (not only the original bid price) of doing business with an individual supplier.

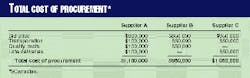

For example, when offers to bid were sent out to three different suppliers, the following prices were received: Supplier A, $800,000; Supplier B, $850,000; and Supplier C, $950,000.

Conventionally, the award would be given to the lowest bidder, Supplier A. Table 1, however, includes all the various costs of dealing with each supplier and in effect paints a different picture of who is the lowest cost supplier.

Based upon the Total Cost of Procurement, the actual lowest cost supplier would in fact be Supplier B.

Procurement strategies

In 1997, TransCanada implemented a series of purchasing strategies to focus the workload into commodity areas that were both high risk and high cost to our business.2

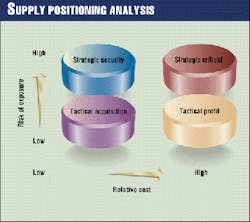

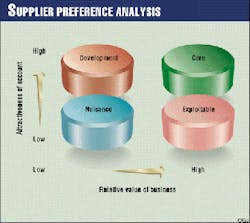

By setting up a "supply positioning" and a supplier preference analysis, Trans Canada was able to determine not only what suppliers were important to its business but establish which supplier felt that TransCanada was important to its business.

Fig. 1 shows the supply-positioning segmentation; Fig. 2, the analysis of supplier preferences. There seems little point in associating with a supplier of a product that is strategically important to you, if the supplier views the customer as a nuisance.

These procurement strategies focused on the following key points:

- Eliminate heavy reliance on buyer knowledge, "gut feel," and lowest purchase price.

- Identify commodities critical (high value, high risk,) to TransCanada's continued profitable operating life. It is essential to maintain ready access of these commodities; otherwise the business will suffer.

- The entire supply chain for critical commodities needs to be assessed to identify vulnerabilities; for example, a pipe mill without a secure steel or plate supplier. This is a risk determination step.

- Qualify only those suppliers whose financial, technical, and quality-management capabilities and physical facilities meet requirements. This results in a list of approved suppliers.

Benchmark orders are placed with a selectively few approved suppliers. If initial order performance meets requirements, these suppliers become the preferred group.

- Ongoing measurement and management of preferred suppliers establishes performance trends. Also, a measurement of the customer by the supplier will contribute to identifying non-value added activities.

If a supportive environment is established with high performing suppliers, through dialog and co-operation, the relationship with the supplier can move from a confrontational one through to a full-blown long-term supply partnering relationship.

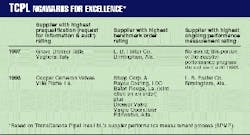

To ensure that high performing suppliers are acknowledged, the SPMP introduced in 1997 an "Awards of Excellence" program.

The highest rated supplier in the elements of ISO Audit, Benchmark Order, and Ongoing Performance (all discussed presently) are presented with a plaque permanently to identify those suppliers whose operations demonstrated "best practice" within their specific industry. (See accompanying box.)

SPMP process

TransCanada developed its supplier performance measurement process (SPMP) in four steps: a request for information, an ISO 9000-type audit, a benchmark order, and an ongoing performance measurement.

RFI

The "request for information" (RFI) measurement consists of four areas felt to be important for any potential business relationship: financial, commercial, quality, and technical.

At this stage of evaluation, all information is obtained via questionnaires. Not all the four components are rated equally, however.

Of paramount importance at this stage is the financial status of the proposed vendor. This general information can be accrued from such financial barometers as annual and quarterly reports.

There have been examples of companies being less solvent than they appeared and even of having gone bankrupt in the middle of a major project. The implications were not only commercial (for example, the purchaser would have to finance the replacement of the commodity), but also have serious effects on the project online date, which in turn would significantly affect customer's cash flow.

The other aspects of the RFI are to identify (without visiting any suppliers' facilities) whether they have the capabilities to meet the requirements of Trans Canada's purchase orders and applicable industry codes.

The supplier would also be requested to identify which, if any, quality programs it has developed or implemented, such as ISO 9002. In the technical area, basic questions arise: Does the supplier have the necessary equipment to conduct industry accepted standard tests such as Charpy impact and tensile tests for line pipe and adhesion and cathodic disbondment tests for coatings?

In addition confirmation of requirements to industry standards such as API, ASTM, and CSA is requested.

Assessing all selected suppliers' financial, commercial, technical, and quality healths affords a level of risk that TransCanada might sustain in a short or long-term business relationship with these suppliers.

Because this is an introductory look at the supplier, this review is not normally shared with the supplier. The exception occurs when a critical defect has been identified: appears unstable financially, does not comply with industry codes, or lacks quality systems.

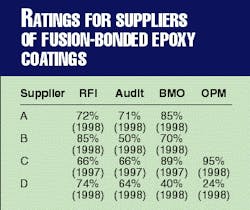

The results of this RFI are then documented and rated accordingly and then recorded in the overall rating systems, examples of which appear in Fig. 3 and Table 2.

Quality audit

Although quality and quality levels have been much discussed recently,3 4 the unresolved and contentious questions center on exactly what is an acceptable level of quality.

Apparently, there is no single or absolute level of quality. Not all products can be produced perfectly; and all products, no matter their costs, may fail.

The challenge for TransCanada was how to establish quality levels that would be fairly applicable to all suppliers. This was finally solved with the application of an audit that met the rigors of the International Standards Organisation (ISO) Quality Management System, commonly referred to as ISO 9000.5

Most suppliers are now developing ISO Quality Programs or have in place fully registered programs. Presentations of TransCanada's quality requirements were unnecessary because both parties were familiar with or actually practiced the principles of the ISO Quality Management System.

The most stringent version of this document (ISO 9001) contains 20 various elements. Suppliers with whom Trans Canada does business and the performance level each delivers vary as much as the commodities they supply. The question for TransCanada therefore centers on what elements should be measured, and the answer is not simple.

The TransCanada program reviewed elements deemed critical to its business and determined that these included, but were not always limited to, the following:

- Management responsibility.

- Organization.

- Quality rystem.

- Contract review.

- Document and data control.

- Purchasing.

- Product identification and traceability.

- Process control.

- Inspection and testing.

- Control of nonconforming product.

- Corrective and preventive action.

- Internal quality audits.

- Training.

Assessing all selected suppliers' critical quality processes provides a comfort level of quality compliance that Trans Canada might expect to encounter during any project or business relationship with these suppliers. As this level is critical for both parties, the results and inferences are shared with that supplier.

As with the RFI, the results of the audit are documented and rated accordingly. The results being documented are recorded in the overall rating systems (Fig. 3; Table 2).

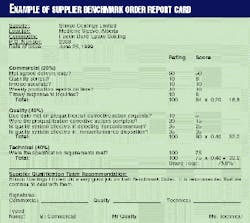

Benchmark order

The third and most critical step in the SPMP is the placement of a benchmark order. This is the first order that is given to the supplier after a successful RFI and ISO audit.

To ensure that all critical requirements have been discussed and understood, TransCanada always arranges a prebenchmark order meeting at the supplier's facilities. This meeting is of particular importance for reviewing on-site any apparent or requested deviations from the TransCanada requirements.

The supplier has the opportunity to give a "hands on" explanation or demonstration of why he requested the deviations. - TransCanada PipeLines' Supplier Performance Measurement Process (SPMP) is designed to match TCPL criteria with supplier performance.

TransCanada regards the BMO as the barometer for establishing whether a supplier is committed to his identified commercial, technical, and quality principles.

The outline and basic criteria for the benchmark order are provided in the "Report Card" (see accompanying box).

The results are shared with the supplier to ensure that any areas for continuous improvement (both for Trans Canada and the supplier) are openly discussed and corrective plans documented for any future orders.

The results are documented and recorded in the overall rating systems (Fig. 3; Table 2).

Performance measurement

This final stage of the SPMP is unique in that it goes beyond the more traditional items of delivery, technical, and quality rankings. This stage introduces improvement initiatives, the objective being to introduce an element which could reap savings in the total cost of procuring a commodity.

At TransCanada, the definition of Total Cost of Procurement includes more than unit price. Costs associated with transportation, poor quality, late deliveries, and inefficient and repeated interaction with the supplier to complete or process orders make up total cost of procurement.

An example of the Total Cost of Procurement has been discussed and is exemplified in Table 1.

The improvement initiatives segment explores where both parties discuss the inherent costs relating to specifications, quality, delivery and their impact on the price and reliability of the finished product.

Areas that have proven favorable have been, for example, savings on transportation, reverting to the use of industry standards and eliminating company specifications, and sharing of reduced prices due to advantages gained by foreign exchange.

The details of the ratings and weightings of the delivery and technical criteria (the criteria for quality and improvement initiatives are not included here) of this ongoing stage of the program appear in the accompanying box for "Performance Indicators."

TransCanada shares the results with the supplier at a point predetermined based upon the volume of business to ensure that any areas for continuous improvement (both TransCanada and the supplier) are discussed and planned corrections documented for any future orders.

An accompanying box provides details of the report card for the ongoing performance measurement of a supplier. These results are documented and recorded in the overall rating systems (Fig. 3; Table 2).

FBE suppliers

The results of the SPMP are lengthy, and for the sake of simplicity we have only provided an example of the program results.

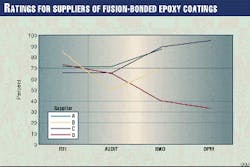

Table 2 and Fig. 3 provide the results of all four stages of the evaluations for the applicators of fusion-bonded epoxy (FBE) high integrity pipe coatings. The results clearly demonstrate a pattern of variation in the performance from one coating applicator to another.

While the performances of Applicators A, B, and C are high and consistent, there is some concern about the performance demonstrated by Applicator D. At this stage of the program, this concern does not necessarily mean that Applicator D will be immediately removed from the approved suppliers list.

It does, however, clearly identify some areas for improvements. At this stage, the applicator would be requested to document his plans to address these areas and, if appropriate, would be given an additional benchmark order to establish that in fact these deficiencies have been resolved and closed.

The overall decision on the final status of the applicators would rest with a demonstrated acceptable performance.

In general, TransCanada's SPMP has been successful in providing the following:

- A system to measure, fairly and consistently, selected suppliers' ability to deliver products and services to Trans Canada's requirements and thereby provide a reference point for identifying improvement opportunities or for setting performance standards.

- A means by which the supplier may identify to TransCanada non-value added activities related to requirements, thereby facilitating continuous improvement in cost reductions and improved delivery.

- A process by which suppliers may identify total cost of procurement reductions, and a mechanism of rewarding successful suppliers.

- A system in which representatives from TransCanada's and the suppliers' engineering, procurement, quality, and production functions are involved in selecting critical technical and service elements to be measured (quality and delivery, for example).

This includes setting performance targets and scenarios (that is, tolerances) for each element that are specific, measurable, realistic, and within the supplier's control.

Lessons; caveats

What TransCanada has so far learned from using the SPMP can be summed in three areas:

1. Individual performance measurement and management programs should initially be developed only for commodities that are strategic, high in value or risk, and represent the greatest opportunity for cost reduction because of capital investment.

The rigors of each program (i.e., elements to be measured and associated tolerances) would vary depending on requirements and historical performance experience with suppliers. In the case of less critical commodities, a development and administration cost-to-benefit evaluation should be done prior to program development.

2. The SPMP has removed subjective statements like, "How would you rate the level of service-excellent, satisfactory, or poor," and is now providing management with performance results that can be objectively derived and are supported with data.

3. The SPMP has now realized a total purchase price cost reduction of up to 6% on some of the more recent TransCanada line pipe and pipe coatings orders.

As indicated previously, the SPMP provides the criteria to identify clearly who are TransCanada's best suppliers for high pressure line pipe and high integrity anti-corrosion coatings.

However, this process should not be regarded as the answer to a buyer's prayer or a "stand alone" tool for determining which supplier receives all of TransCanada's future work. This is just one tool available to senior management when making the decision on the dissemination of future orders.

It is not possible to identify or list all the various situations that may occur when procuring these types of commodities. For instance, if the project is international, there may be government restrictions, which would only permit the consideration of domestic suppliers.

If the pipe is purchased in Canada, it would make no commercial sense to ship the pipe to the best supplier of coatings, who happened to be located in Japan, for the coating applications. Sometimes increasing inspection at the location of moderate performers, to ensure compliance with the codes, actually provides the lowest "total cost of procurement."

Management has to consider all the salient factors including company strategies when determining from whom to procure strategic critical commodities. The SPMP provides management with another valuable tool upon which to make an informed decision.

References

- Coulson, K.E.W., Quinton, D.G., Slimmon, T.C., "Application of Material Standards and ISO Quality Management Systems," ASME International Pipeline Conference, Calgary, Canada, Vol. 2, p. 619, June 1998.

- Steel, P.T., Court, B.H., Profitable Purchasing Strategies, McGraw-Hill Publishing Co., 1996.

- Crosby, P.B., Quality is Free, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1979.

- Deming, W.E., Out of the Crisis, MIT Centre for Advanced Studies, 1982.

- ISO 9000, International Standards for Quality Management, Geneva, Switzerland.

The Authors

Keith Coulson recently retired from TransCanada Pipelines/NOVA after nearly 22 years. He has been appointed technical vice-president of Jotun Powder Coatings of Norway.

Coulson was educated at the University of Swansea (Wales) and Aston University (Birmingham, England), receiving an MSc in 1976. He is a fellow of the Institute of Corrosion, a NACE Corrosion Specialist, and chair of the Canadian Standards Association/ASTM Pipeline Coatings work team.

Tom Slimmon is a materials engineer in the quality, standards, and technology department at TransCanada Transmission. He worked for NOVA Gas Transmission before its merger with TransCanada. Slimmon holds a BSc in metallurgical engineering from the University of Alberta and is a registered professional engineer in Alberta and Yukon Territory, an accredited NACE Corrosion Specialist, and a Certified Lead Auditor (ISO 9000). He chairs the Canadian Standards Association subcommittee on materials.

Alan Murray is director of procurement and inventory management at TransCanada Transmission. He worked for NOVA Gas Transmission before its merger with Trans Canada. Murray holds a BSc in mechanical engineering and a PhD in civil engineering from the Queen's University, Belfast. He is a registered professional engineer in Alberta.

Nestor Puka recently retired from Trans Canada Pipelines/NOVA after nearly 18 years. He is now a consultant in implementing quality management programs (ISO 9000) and in management of suppliers' performance. Puka's formal education is in Industrial Engineering, and he is a long time member of the American Society of Quality.