Oil-prospective Spratlys still a flashpoint

The South China Sea's Spratly Islands continue to be a potential flash point as China persists in following a long-term strategy of gradually extending its control over the entire South China Sea.

That poses a major concern for oil and gas companies that see the waters surrounding the islands as holding significant hydrocarbon potential. Exploration licenses awarded by both China and Viet Nam in disputed waters there have contributed to rising tensions in the region. Exacerbating the problem has been the recent round of saber-rattling between China and Taiwan over Taiwan's status.

China's opportunism

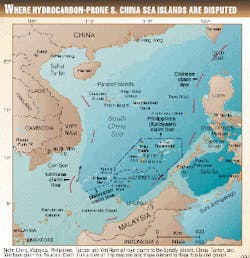

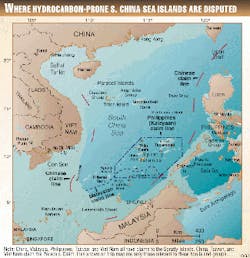

China's bolstering last December and January of military facilities on the Spratlys' Mischief Reef-that it first occupied in 1995, just 135 nautical miles off the Philippines (Fig. 1)-and its dispatching of two naval vessels to oversee the work has been remarkable for the lack of response it has engendered.

Although Beijing pays lip service to the notion that the structures are being constructed by and for fishermen, none of the claimants to the Spratlys doubts their military function. Moreover, the accompanying naval presence (frigates and supply vessels) lies well within the Philippines' 200-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ)-the area off the Philippines coast falling under Manila's sovereignty as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

It is difficult not to admire China's ability to follow through on a regionally provocative policy. China has taken advantage of the Association of South East Asian Nations' (ASEAN) preoccupation with the recent Asian economic crisis and is moving steadily towards realizing its goal of controlling all of the South China Sea. The Mischief Reef fortifications have been conducted with virtually no protest from ASEAN, or even from major powers-particularly the US and Japan, which have a vital strategic interest in the sea lanes.

Moreover, Beijing has spurned an offer by Manila to jointly develop the reef, something that it was previously pushing as a possible solution. Even worse, it has politely told the Philippines that it would be best if the country kept its air force planes flying above 1,500 m and that its ships maintain a 5-mile exclusion zone around the reef.

China's intentions

Regional specialists warn that the Spratly Islands remain a potential flash point and that oil and gas operators considering entering into contracts covering acreage in the region need to seriously assess the potential ramifications.

"While we have entered a period of preoccupation due to the (Asian) economic crisis, there is absolutely no indication that either the Chinese or the Vietnamese, the two principal claimants, view their claims to the area any less seriously," said one legal expert on regional territorial disputes. Fig. 2 (at right)

For its part, China does not mince words about its intention to follow through on its Spratlys claims: "The Spratly (Nansha) Islands have been an integral part of the territory of the People's Republic of China since ancient times, as international historians and archaeologists have proven," says a statement to the Asia and Pacific Council issued by the Central Committee in 1991. "Regional powers, initially taking advantage of China's previously turbulent domestic politics and our preoccupation with superpower threats, have occupied China's islands and reefs, carved up our sea areas, and looted our marine resources. Past and current foreign occupation of these islands does not change the fact that these islands are an integral part of China, though. Foreign reluctance to recognize the revival of Chinese power and to relinquish Chinese territory is the only obstacle to peace in this region. It must be overcome."

Such comments mirror the Beijing party line for more than 2 decades, as China has persisted in its claims that it owns all the island groups in the South China Sea and waters extending for 200 miles in all directions around them (OGJ, Nov. 26, 1979, p. 19).

In the light of China's size, economic vigor, military upgrading-particularly its air force and navy-and its past conflicts with other nations in Southeast Asia, it is not surprising that China's moves in the Spratlys in the past have reinforced fears about its intentions in the region. The lack of transparency of Beijing's approach, especially in the military area, has produced different assessments of China's security policy towards Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific region in general. Given China's limited naval capability at present to take and hold the islands, some see a pattern of hot-and-cold tactics by China that is intended to throw the other claimants off balance until it is able to enforce its claim through intimidation or force.

"China's pattern could best be described as 'thrust and reassure,'" said one diplomat. "It is a steady sequence of small encroachments, each followed by protestations of peaceful intentions."

The recent encroachment is a continuation of a goal set several centuries ago to dominate the South China Sea, and it follows a pattern dating to 1992: Be willing to talk about the area and offer the prospect of joint development with other claimants while proclaiming total sovereignty and creating realities when opportunities arise. It has been an effective strategy.

In 1974, China grabbed the Paracel Islands from a divided Viet Nam; it then employed naked military force against a diplomatically isolated Viet Nam in 1979 and 1988 to wrest control of Vietnamese positions on Fiery Cross Reef.

Conflicting interpretations

The South China Sea is an area of 648,000 sq miles dotted with hundreds of reefs, islets, rocks, and shoals, all of which are the subject of conflicting territorial claims. Like many islands, distant from the mainlands, that are claimed by different powers, the Spratly Islands group has been the subject of recurrent and sometimes concurrent assertion of ownership by different countries, often without the knowledge of other existing claims.

Located in the southern reaches of the South China Sea, the Spratly Islands are spread across the world's busiest sea lanes and are claimed by China, Taiwan, Viet Nam, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Brunei. Although their claims overlap, all six maintain that their titles are fully supported by UNCLOS, according to Mak Joon Num, director of research of the Maritime Institute of Malaysia.

"Differing interpretations of the Law of the Sea by each country involved merely enable each to claim legality," Mak said at a recent conference. "Unfortunately, international law may just make the entire situation more complicated."

Although unproven with regard to hydrocarbon potential, the Spratlys are thought by many analysts to contain significant potential for commercial reserves of natural gas and oil. Just how much is in the Spratly Islands region has yet to be determined. Chinese geoscientists have postulated the Spratlys-area hydrocarbon resource potential at 70 billion boe, although little seismic or drilling activity has been undertaken on the southern portion of the Shunta continental shelf where the islands are located. Both Chinese and foreign operators have discovered a number of large oil and gas fields in South China Sea waters closer to the mainlands but still theoretically on trend with prospects in the Spratlys-notably near China and Viet Nam.

Since 1974, Chinese maps include an EEZ of 371 km around the Spratly Islands. This, in turn, cuts into part of Indonesia's vast Natuna Sea gas field near Natuna Island. Although on the back burner, Exxon Corp. has outlined a $40 billion project to develop the high carbon dioxide-content Natuna gas reserves (OGJ, Feb. 8, 1999, p. 23).

With several notable exceptions on the part of China, both China and Viet Nam have mainly engaged in a deliberate strategy of using non-military means-chiefly oil exploration contracts-to reinforce their positions and probe opponents' weaknesses.

Over the past year, Viet Nam has also used its prospective undisputed offshore blocks as bait. Government officials have told operators unofficially in negotiations that their applications for attractive undisputed blocks would be viewed more favorably if they were willing to sign contracts for disputed acreage in and around the Spratly Islands, industry sources say.

Overlapping claims

The question of who owns the 400-odd rocks and islands that comprise the Spratlys was largely ignored until the mid-1970s. Factors that have brought the issue forward for the various countries involved are the rise of nationalist political pressures and the maintenance of political legitimacy.

"The tangled web of overlapping claims in the Spratlys defies any attempt at disentanglement," said Lee Lai To, chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs. "Nationalistic fervor based on history and domestic political priorities renders any compromise-at least over sovereignty-difficult, if not impossible."

During the 1980s and 1990s, most of the disputing states have attempted to bolster their claims by gaining occupation of the islands that can support a physical presence or by establishing markers where physical occupation is not possible.

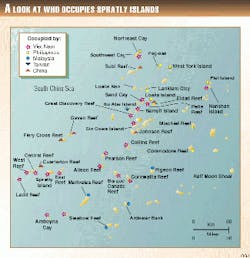

Some countries have gone so far as to set up markers that are actually under water during high tide. Currently Viet Nam occupies over 20 islets or rocks, China 8, the Philippines 8, Malaysia 3-6, and Taiwan 1 (Fig. 2).

The race to reinforce the validity of the various claims has increased the likelihood of diplomatic discord and even resulted in three cases of military intimidation over the past 11 years, the first of which led to armed conflict. This confrontation occurred between China and Viet Nam in the late spring of 1988 when Beijing sank three Vietnamese naval vessels, killing 72 people, and took over Fiery Cross Reef.

In 1992, the Chinese announcement that it had awarded an oil concession to Crestone Co., occupied another reef, and deployed three conventional submarines to patrol the area caused considerable consternation within ASEAN (OGJ, July 13, 1992, p. 20).

The third incident, in February 1995, involved encounters between naval vessels of China and the Philippines at Mischief Reef. The Mischief Reef incident brought high-level attention to the dispute and catalyzed a united ASEAN reaction, to which China eventually responded in a conciliatory manner.

The latest Chinese thrust on Mischief Reef is a continuation of Beijing's strategy. Once regional opinion simmers down and people lose interest, it carefully chooses an appropriate opportunity to extend its presence.

International law

The documentary background of the various claims in the Spratlys is quite thin, and the historical records quite contradictory. None of the countries involved offers completely convincing historical or legal claims. Setting the stage for the current contest to justify titles, the International Court of Justice has designated "effective occupation" as a primary consideration in the evaluation of claims, according to Richard E. Hull of the US Institute of National Strategic Studies.

Separate from the issue of which nation has sovereignty over the rocks and islands is the question of whether the islands can themselves "sustain human habitation or economic life of their own." This is the minimum criterion for an island to generate its own continental shelf or EEZ. Even if human life can be sustained, islands carry less weight than continental borders in generating EEZs under the prevailing interpretations of the Law of the Sea, said Hull.

Artificial islands on which structures have been constructed are entitled to a 500-m safety zone, but they cannot generate a territorial sea, much less a continental shelf or an EEZ. Features that appear only at low tide can generate a partial 12-mile territorial sea if they are within 12 nautical miles of any feature that generates a territorial sea. Features submerged at low tide are not subject to sovereignty claims and generate no maritime zones whatsoever.

US policy

The US is currently viewed by ASEAN as the principal deterrent to any outbreak of military hostilities in the South China Sea. Washington has significant economic and strategic interests in Southeast Asia and a mutual security treaty with the Philippines. The official US policy on the South China Sea and the Spratlys is that it takes no position on the legal merits of the competing claims. However, freedom of navigation is a fundamental interest to the US, and it would view with "serious concern" any maritime claim or restriction on maritime activity in the area not consistent with international law.

"This policy implies that the United States would not tolerate any claimant closing off large, navigable portions of the South China Sea," according to the Institute for Strategic Studies.

Taiwan's claims to Chinese ownership of the Spratlys are similar to those of China, and there has been some evidence of coordination of positions in Indonesian workshops on the South China Sea.

The Philippines claim is based on the discovery of the unclaimed islands of Kalayaan (Freedomland) by an explorer, Tomas Cloma, in 1956. This is one of the most-challenged claims, and Washington has consistently interpreted the US-Philippines security commitment as excluding Kalayaan.

The Malaysian claim is based on its continental-shelf claim, while the Bruneian claim is also based on a straight-line projection of its EEZ as stipulated by UNCLOS.

ASEAN's position on the Spratlys looks increasingly ill-suited to the challenge that the dispute poses. Its talk of diplomatic mechanisms to achieve a solution pales in comparison with China's willingness to create physical encroachments. Moreover, China's unwillingness to discuss the matter in a multilateral forum belies its intentions, the diplomat says, contending that Beijing clearly intends to take on each claimant in turn, using a variety of options, never deviating from its long-term goal.

"They will pick them off one by one," said the diplomat. "Not within any concentrated period of time but over decades."

ASEAN is particularly vulnerable to China's strategy at the moment. Dealing with the economic crisis has reopened old schisms within the group, making it difficult to react in a unified manner as in the past. There is also the possibility that China is feeling emboldened due to its increasingly positive relations with Washington.

The choice of the Philippines as China's latest antagonist in this long saga is hardly surprising. The country is the weakest militarily of any of the claimants-with the exception of Brunei. And from China's perspective, the Philippines' offshore rocks and reefs are by far the most strategically imperative. The region is just miles away from oil fields exploited by Manila but in waters claimed by China. And just to the north are islets where China has put down a marker. The marker lies just west of Subic Bay-now a major refined products regional distribution hub operated by the Philippines.

"China is taking the long view, and it's working," said the diplomat. "All the talk about the Law of the Sea and international or regional forums is whistling in the wind. China is implementing a slow-motion fait accompli."