Oil piracy poses growing menace to tanker traffic in South China Sea

Oil piracy carried out by sophisticated and well-connected syndicates is a growing menace to petroleum tankers in the greater South China Sea area.

The modern-day pirates, often armed with assault rifles, use cellular phones to coordinate attacks and speedboats to board ships. They are then able to organize ship-to-ship transfers of fuel.

Sophisticated networks of black-market crude oil dealers throughout the region enable them to dispose of oil products worth millions of dollars relatively quickly. According to oil traders, diesel fuel is the preferred loot.

Aside from the potential damage done to petroleum and shipping companies' bottom lines, a major threat of environmental or human disaster looms with this worsening trend.

Recent incidents

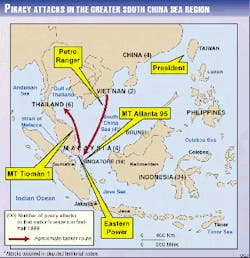

The pirates' growing sophistication was displayed by a seizure earlier this year: that of the Singapore-owned tanker Petro Ranger. The vessel was carrying 11,000 tonnes of diesel and kerosine when it was attacked on Apr. 17. While sailing from Ho Chi Minh City to Singapore, 12 pirates wearing balaclava hoods came alongside in speedboats and climbed aboard. They dragged the terrified Australian captain and the 21-person crew to the bridge, strapped the captain to a chair, and held a machete to his throat and groin. Shortly thereafter, a lightering vessel pulled up and began unloading the tanker's cargo.

Two other tankers, both carrying diesel fuel, have also been hijacked and their cargo stolen recently. The MT Atlanta 95, laden with 3,000 tonnes of diesel fuel, was hijacked as it sailed through the Riau Straits off Sumatra. The pirates manned the Indonesian-flagged tanker and took it to the Gulf of Thailand, where the entire cargo was transferred to another, unregistered tanker. The pirates sailed the Atlanta tanker for 3 days before abandoning the vessel. The crew forced their way out of a locked cabin and were later rescued unharmed. The pirates had destroyed all of the tanker's communications equipment and the navigational charts.

A Honduran-flagged tanker, the MT 1, was hijacked off Pulau Aur along the eastern coast of peninsula Malaysia as it was heading towards the Gulf of Thailand. Pirates boarded the tanker armed with knives, pistols, and rifles. The pirates took 800 tonnes of the tanker's 2,500-tonne diesel cargo and left on the same day.

Growing crisis

Simply put, piracy is rife on many of Asia's sea lanes. Maritime officials are expressing serious concern that growing violence on ships in the region could lead to an environmental catastrophe, either a major oil spill or-even worse-an explosion on an LNG tanker.

The concern emanates from continued reports of crews being tied up during pirate attacks, leaving the ships-including very large crude carriers and LNG carriers-in danger of groundings or collisions. "This tying up of crews is not fiction, this really happens," said Ove Tvedt, deputy secretary general of the Baltic and International Maritime Council.

There is plenty to be worried about. According to Tvedt, even though the number of attacks is going down, the violence is becoming more pronounced, and, more frequently, guns are involved. In one attack against a fully laden tanker, six men armed with machetes boarded the ship, slashed one seaman and the captain-the only ones on the bridge at the time-and left the ship to drift on its own. The tanker steamed out of control less than a kilometer off the eastern coast of Indonesia before the attack was thwarted.

An attack last year on the Panamanian-registered tanker President in the South China Sea just west of Taiwan also illustrates the concern. As the President steamed northward in the densely foggy night, suddenly a high-powered speedboat appeared out of the fog on the port side, and its occupants directed a searchlight at the vessel and opened fire with M-16 automatic weapons. The speedboat then attempted to draw alongside to board, and the President's captain began zigzagging in response, at times ramming against the pirate boat.

The attack lasted 15 min before the marauders gave up. There were no injuries, and the President, which was carrying 50,000 tonnes of naphtha, did not receive any hull damage or lose any of its cargo.

The attack, which occurred recently, was hardly an anomaly. In late May, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) issued a global warning about pirate attacks on ships passing through the Singapore Strait. Pirates attacked 18 ships in the Singapore Strait in the first 6 months of the year, according to IMB. A total of 72 attacks took place in the Southeast Asia region during that period. Indonesia's waters were the most dangerous in the region, with 34 piracy attacks. Singapore was second with 18, followed by Thailand with 6. Malaysia, China, and South China Sea (assigned to no one nation because of disputed territories) each had four reported attacks, and Viet Nam had two.

"Piracy and sea robberies present a serious threat to safety of life at sea and the marine environment," said Lee Seng Kong, director of shipping at the Maritime & Port Authority of Singapore. "Imagine what would happen if a loaded very large crude carrier was attacked by pirates and left without a navigator while transiting busy waterways, such as the Malacca and Singapore straits. Not only would this result in a major ecological disaster to the detriment of the coastal states, it could disrupt the passage through one of the world's busiest waterways."

Hot spot

A glance at a map or a short boat ride through the maze of about 180 islands at the southern end of the Strait of Malacca shows how easy it is for pirates to operate. About 700 commercial ships pass through the strait and its network of surrounding waterways every week. A number of small boats also ply these waters, ferrying passengers and goods and darting between passing cargo ships. The boatmen are experienced, and their little vessels are fast and maneuverable.

The Phillip Channel is the most perilous waterway in the strait. Located just 16 km from Singapore, the 8-km long channel narrows to a mere 0.5 km, forcing vessels to slow to less than 10 knots and to move closer to uninhabited islands where pirates lurk. Malaysia and Singapore are both less than an hour away, and the opportunities for smuggling and other illegal activities are numerous.

"In the beginning, most pirates were probably fisherman looking for an easy grab," said one shipping official. "Now they are much more ambitious and sophisticated. Maybe they've got more money." Indeed, the sophistication level of the pirates' organization and planning-attacks often take just minutes to transpire-suggest to some that there is some military involvement in many cases.

In recent years, there have been numerous attacks in or near Chinese waters. The pirates, usually on speedboats that come from larger ships, wear military fatigues, and shipowners suspect rogue military elements in some of the incidents.

Pirate methodology

Fears of an environmental disaster top the list of concerns as large tankers or LNG carriers emerge as the vessels of preference. They are prime targets when loaded because the freeboard-the space between the waterline and deck-is shortest at that time. Such large vessels are also the most vulnerable to attack because they carry a crew of only 20, and with a length as great as 480 m, they can be easily boarded undetected.

Armed with Uzis and M-16s, pirates draw alongside in high-powered speedboats, then clamber up the stern with grappling hooks and slings and usually head for the captain's cabin. Commonly operating in groups of five or six, they seldom spend more than an hour on board and move with military precision. Attacks are often patterned after commando raids. Under the cover of darkness, pirates converge on a ship, usually between 1:00 and 4:00 a.m., when most crew members are asleep. Pirates often carry sophisticated radar equipment to monitor nearby traffic and police activity, as well as to jam communications equipment.

But not all attacks are swiftly executed, and that is where the main environmental danger lies. The possibility that an LNG carrier or tanker could slam into another ship or ground ashore with disastrous ecological consequences during an extended attack is real. Several years ago, the supertanker Eastern Power, carrying 240,000 tonnes of crude oil, was raided in the Phillip Channel. Its crew members were tied up, and the mammoth tanker was left cruising completely unpiloted for over 10 min.

Even worse, IMB Deputy Director Capt. Jayant Abyankar told a piracy conference in Singapore earlier this year of an incident when thieves boarded a tanker in the Strait of Malacca off Malaysia, tied up the crew, and left the vessel steaming on automatic pilot through the world's most congested shipping lane. It took 11/2 hr for the crew to wriggle loose and return to the bridge.

"Had this incident taken place in the Phillip Channel, a disaster would have been virtually inevitable," Captain Abyankar said.

Spill threat

If a spill of the magnitude of the Exxon Valdez had occurred in the Phillip Channel, oil pollution would extend well into the narrow Malacca Strait straddling Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore, according to Capt. Abyankar.

"Given the necessary combination of wind and tide, the oil would completely surround Singapore Island and the multitude of islands that form this part of Indonesia," he said. "Apart from pollution consequences, there is every possibility that the seaway would have to be closed to shipping, and the fishing in the area would be ruined for years, if not permanently."

Worries over such a contingency have spawned a new company dealing exclusively with quick responses to oil spills. Six of the most active operators in Asia-Royal Dutch/Shell, Exxon Corp., BP Amoco PLC, Mobil Corp., BHP Petroleum Pty. Ltd., and Caltex Corp.-several years ago formed East Asia Response Ltd. (EARL) as a nonprofit venture that provides equipment, expertise, and training facilities for fighting oil spills. Capable of responding anywhere in the Asia-Pacific region, EARL can provide both airborne and waterborne equipment to deal with a full-blown oil spill crisis.

The majority of EARL's resources are located in Singapore, with another, smaller base at Port Dickson, Malaysia. The JV company spent about $20 million for capital equipment and start-up costs. It has planned annual operating costs of $7 million and is currently seeking as many other members as possible.

There are a few other things that can be done to alleviate the environmental dangers posed by piracy. According to IMB officials, shipowners and oil and gas companies can cut back on automation, a trend that has vastly reduced crew sizes, making vessels more vulnerable. Increasing the number of security personnel on board, and training and arming them sufficiently, is clearly another option. Although politically touchy, cooperation between local authorities would also help. A successful new patrol policy that has recently been implemented by Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia could be expanded to include other countries as well as coordinated intelligence of known pirate vessels and lairs.

Shippers and governmental authorities can also cooperate. Shipping associations made proposals at the recent piracy conference to put regional security forces aboard tankers in certain areas to form a 24-hr piracy center, where all sides could share information.

While it may have its roots in ancient times, piracy is a modern, complex problem more prevalent now and with the potential of having a greater environmental impact than at any time in its history. And it seems only a matter of time before a piracy-connected environmental disaster brings that to the front pages.