This article is adapted from the author's comments during a joint conference of CGES and Oil & Gas Journal on the oil price challenges of the next century, held Sept. 9-10, 1999, in Houston.

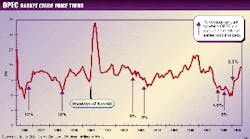

A year and a half ago, oil prices looked as if they were heading for a crash. Well, they certainly did just that, reaching a 12-year low in December last year, despite two rounds of output cuts by the member-states of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Since then, however, the price of West Texas Intermediate has almost doubled, thanks to OPEC's third round of cuts. At first sight, this might suggest that all the oil industry's problems have suddenly evaporated and that there is nothing more to worry about. Why talk about oil price challenges when oil company cash flows are strong once more and OPEC's oil revenues are expected to rise this year by $24 billion?

I am of the opinion that the oil industry still faces serious challenges, notwithstanding the high oil prices we are seeing at the present. OPEC's actions have not really solved any of the deep-seated and long-standing problems that plague the industry. Indeed, I would argue that the OPEC-engineered oil price rises of 1999 have added to the industry's catalogue of worries.

Worse than it seems

For a start, one must bear in mind that the oil price rebound of 1999 has clawed back only a portion of the dramatic oil export revenue losses experienced by OPEC countries in 1998. OPEC's oil revenues dropped by $51 billion (43%) last year as a result of the 42% crash in oil prices.

CGES estimates that OPEC will have recouped only half of this loss in 1999, leaving a lot more to be done in 2000. In fact, the center estimates that OPEC's oil export revenues in 2000 will barely equal the $148 billion it earned in 1997, implying that OPEC will almost certainly be worse off, in real terms, than it was only 3 years ago.

What I am really trying to say is that OPEC has hardly achieved a resounding success-it has merely averted disaster.

Furthermore, OPEC has achieved a 43% increase in the prices since April 1998 by shutting in almost 4 million b/d of oil production. Its excess capacity right now is no less than 7.5 million b/d, representing 10% of world consumption.

A staggering 43% of this excess production capacity is held by Saudi Arabia, with another 40% attributed to Iran, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela. Such a massive amount of oil-ready to be produced at almost a moment's notice-will keep hanging like Damocles's sword over the oil market, with one country seemingly carrying the entire burden.

Restraint needed

Not since 1988 has the market had to contend with spare capacity in excess of 9% of world demand. Obviously, enormous self-discipline will need to be exercised by all the OPEC member-states to keep this oil from entering the market.

So far, discipline has not been a problem for OPEC, but as the oil price gets ever higher, the centrifugal forces within OPEC will get ever greater-as standard cartel theory predicts. With the OPEC basket price at $20/bbl and likely to head towards $25/bbl during the coming winter, the temptation by each OPEC country to produce an extra barrel (provided no other member-country does the same) will surely grow.

Apart from placing great strains on OPEC itself, the recent burst of oil price rises is also bound to tease out, in due course, more supplies from many non-OPEC producers. Already, Canadian upstreamers are revving up their capital expenditures in the second half of 1999, having slashed expenditures by around 20% last year. The upward spending charge in Canada is led by the heavy oil producers, who account for almost 40% of the country's output.

As you well know, oil production in the U.S. is in long-term decline because of the age of onshore fields in the Lower 48 states. However, the 400,000 b/d drop in U.S. production seen this year is unlikely to be repeated in 2000 if oil prices stay above $20/bbl.

As for the North Sea, I would simply like to cite Royal Dutch/Shell's claim that its operating costs there are no higher than $4/bbl. With oil prices above $20/bbl, earnings from Shell's and other companies' North Sea operations will be greatly increased and should lead to much higher spending on upstream activities.

Production rebound

You will have gathered from these remarks that non-OPEC output should rebound in 2000, after the 150,000 b/d drop recorded this year, for there is little doubt that higher oil prices encourage greater supplies.

Following the price explosions of the 1970s, non-OPEC countries' share of global oil production rose rapidly, from 44% in 1973 to a peak of 71% in 1985. Thereafter, as a result of the price crash of 1986, non-OPEC states' share of output dropped once again, stabilizing at around the 59% level we have at present.

The sensitivity of non-OPEC oil supplies to changes in the oil price is significant, and history has shown that OPEC disregards this fact at its peril. These predicted changes in output take time, however, which is why non-OPEC production's lack of immediate response is often misunderstood.

Let us also not forget that most OPEC countries are planning to increase their own capacity, and a number of them are trying to encourage foreign companies to help them do so. Iran, Kuwait, U.A.E., Libya, Algeria, Nigeria, and Venezuela all hope to expand capacity, expecting to add a combined 3.2 million b/d by 2005.

Of these, the U.A.E., Algeria, Libya, and Nigeria already have a considerable foreign presence in their oil sectors, and Iran and Kuwait are seeking foreign involvement (OGJ, Sept. 13, 1999, p. 27; Sept. 6, 1999, p. 24).

This does not include Iraq, which should be able to increase its oil production capability by around 3 million b/d within 5 years of sanctions being lifted. Nor does it include Saudi Arabia's ability to expand its capacity, because it can hardly be thinking of such matters at the moment, in view of its 3.2 million b/d of idle capacity.

By the way, there are no free lunches, even when it comes to spare capacity.

CGES estimates the cost to Saudi Arabia of maintaining its idle capacity at $500 million each year, which adds 17¢ to the cost of every barrel it produces.

Likewise, the cost to Venezuela of keeping 0.8 million b/d of capacity unused is around $240 million/year, or 24¢/bbl of production.

Restraining output obviously pushes prices up and improves the OPEC countries' financial situation in the short term, but it comes with some heavy baggage too.

Demand pitfall

Another consequence of higher oil prices is the adverse effect they have on oil demand.

The collapse in oil consumption in the Far East in 1998 was a prime cause of last year's oil price crash. Recovery is now under way in Asia, led by South Korea, hence Asia's expected 0.5 million b/d (50%) contribution to global incremental demand this year.

However, the doubling of crude prices since February is hardly likely to help oil demand growth in that region, especially because Asian oil product taxes are not as well-insulated from crude price changes as is the case in high-tax countries.

On the question of prices, one must bear in mind the distinct likelihood that the long-run sensitivity of oil demand growth to price changes is not far from unity. Research at the center suggests that this is indeed the case with respect to gasoline, denoting that oil demand responds eventually on a one-to-one basis with oil price movements-it just does not happen straight away.

Outstanding issues

In gazing over the horizon, there looms an even bigger threat to oil demand than higher oil prices: implementation of the Kyoto Protocol.

At least higher oil prices lead, in due course, to lower demand and more non-OPEC oil-feedback effects that do bring about a price correction. By contrast, the Kyoto Protocol requires a substantial worldwide cut in hydrocarbon consumption solely by government fiat.

I am sure such a cut will be implemented, in practice, by raising fuel prices via a tax increase, but this immensely important subject is beyond the scope of this article (see story, p 28).

Neither will I discuss technological developments that have the potential to threaten oil's ascendancy, such as gas-to-liquids plants and fuel-cell applications in transport and power generation.

What I would like to come back to, instead, is what one could describe as OPEC's misguided mindset.

OPEC/non-OPEC battle

Faced with the threats I have mentioned, who needs higher oil prices, or even the latest idea from OPEC's principal players-a managed price band of $18-21/bbl?

Do not get me wrong: There is nothing flawed about aiming to stabilize oil prices within a band. The problem is the band that has been chosen.

In my opinion, $18-21/bbl (which means $19.50-22.50/bbl for WTI) is too high a target, because it will give non-OPEC producers every incentive to explore for and develop new supplies. It will also slow demand growth, for at the upper end, it implies a gasoline price of $1.60/gal in the U.S.

This is a lot higher than the price of gasoline today in the states, and it represents a level that will surely knock back oil consumption growth.

Advice for OPEC

What should OPEC do?

It is not easy to recommend a course of action, for OPEC seems to be damned if it does (raise prices) and damned if it doesn't. As far as the immediate future is concerned, I think that OPEC should announce at its forthcoming meeting in Vienna that it will increase production from next March onwards. This will have the effect of dampening the overheated oil market over the early winter period.

Regarding the longer term, OPEC needs to develop a strategy that keeps oil prices constant, in real terms, at a level low enough to deter non-OPEC producers from adding to their reserves and keep worldwide demand growing at a healthy rate. What this level should be is, of course, open to vigorous debate. But whatever it is, it should ensure that the demand for OPEC oil rises steadily to absorb its huge excess capacity, both at present and in the future.

I would like to add that OPEC's member-states should restructure their economies and fiscal regimes in such a way as to learn to live with whatever level of prices is commensurate with OPEC's longer-term interests. In other words, OPEC countries should not allow the tail (their governments' overspending) to wag the dog (their oil sector's future prosperity).

It is always difficult to advocate lower oil prices, but I honestly believe that we will all benefit in the longer run.

The Author

Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani is chairman of the Centre for Global Energy Studies, London. Before founding CGES in 1990, he was Saudi Arabia's minister of petroleum and mineral resources during 1962-86.

Sheikh Yamani received a masters degree from New York University in 1955 and a master of law from Harvard University in 1956. He opened Saudi Arabia's first law office in 1957 and became legal adviser to the Council of Ministers under Crown Prince Faisal. In 1959, he was appointed a minister of state and a member of the cabinet, and he continued to teach law part-time at King Saud University during 1957-60. In 1963, he established the University of Petroleum and Minerals in Dharan and remained its chairman until 1976.

Today, Sheikh Yamani continues to lecture on Islamic law at Harvard.