Kyoto pact deemed threat to U.S. economy-or boon to oil firms

The much-discussed U.S. federal budget surplus could be endangered by an economic slowdown stemming from efforts to comply with the Kyoto Protocol on climate change.

That concern may be rendered moot, however, as the odds continue to stack up against any effective implementation, in its current form, of the global climate change treaty. If the treaty is implemented as envisioned, it could represent a significant business opportunity for petroleum companies in the renewable energy sector.

Those are the key points of talks by participants in a panel on the challenges that the petroleum industry faces with global warming and the Kyoto Protocol, part of a conference on oil price challenges into the next century co-sponsored by London's Centre for Global Energy Studies and Oil & Gas Journal (see related stories, pp. 23 and 25).

Budget crunch

Reducing U.S. emissions of greenhouse gases to meet the Kyoto goals would, in effect, ration the use of energy in the U.S. and require large taxes-imposed directly or indirectly, in the form of required permit purchases-noted Margo Thorning, senior vice-president and director of research at the American Council for Capital Formation's Center for Policy Research, Washington, D.C.

Thorning contends that full compliance with Kyoto-or a backdoor approach via regulatory policy-could have serious economic implications for Americans and that these implications are not fully understood.

She cited a wide range of models predicting that cutting U.S. CO2 emissions to meet the Kyoto target (7% below 1990 emission levels), or even trimming them to 1990 levels, would reduce U.S. gross domestic product growth significantly. Meeting Kyoto goals would cut U.S. GDP by 1-4%/year, or $100-400 billion/year, in inflation-adjusted dollars.

ACCF's research found that just reducing U.S. emissions to 1990 levels would slash wage growth by 5-10%/year, and the lowest-income quintile of the population would see its share of the economy shrink by about 10%. Another study Thorning cited found that U.S. living standards would fall by 15% under the Kyoto Protocol vs. the base case energy forecast. Furthermore, the competitiveness of energy-intensive industries in the U.S. would be eroded significantly by efforts to comply with Kyoto targets. Studies show that U.S. output of autos, steel, paper, and chemicals could be 15% less than the reference case by 2020.

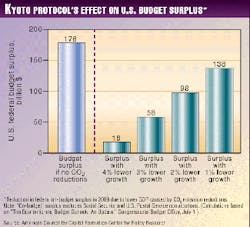

"In light of the current debate about how to use the projected federal budget surpluses, policy-makers need to consider the potentially large negative impact on GDP growth and federal budget receipts of proposals that address the potential threat of global warming by requiring sharp, near-term cutbacks in CO2 emissions," Thorning said. "A report by the Congressional Budget Office shows that, if (U.S.) economic growth slows relative to the baseline forecast and GDP were 4% lower in 2009, the projected on-budget surplus (excluding Social Security contributions) virtually disappears (see chart).

"Therefore, implementation of the Kyoto Protocol would make it much more difficult to sustain tax cuts, 'save' Social Security, promote the retirement security of the 'baby-boom' generation, or achieve other public policy goals and could require sharp changes in fiscal policy in order to avoid deficit spending."

Thorning contends that even meeting Kyoto goals is a virtual impossibility, citing the massive economic contraction in the U.S. that followed the energy crises of the 1970s, which resulted in only a 1% decline in CO2 emissions from baseline projections, compared with a 2% decline from the baseline called for under Kyoto.

She cited other, less economically destructive options available to Kyoto participants, given the extremely long time scale for global climate change:

- Step up research into carbon sequestration technology, which holds the promise of reducing costs of meeting Kyoto goals by as much as 75%.

- Increase spending for research and development of new energy technologies for the next 25 years.

- Begin to enforce carbon emissions caps around 2025, if the best available science shows such caps are needed.

- Phase out the venting of carbon around 2050, if necessary.

- Reform the tax code to encourage the adoption of energy-efficient equipment and new technologies.

Treaty outlook

Clement Malin, a retired Texaco Inc. vice-president of international relations, outlined a status update on the Kyoto initiatives while calling on the petroleum industry to recognize that it must play a critical role in the debate.

According to Malin, there remain huge hurdles for the treaty to be adopted-not the least of which are the many commitments and constraining features that require detailed elaboration. Such open issues are not trivial, he contends, noting that how they are resolved will have enormous economic and social significance.

To implement the treaty calls for domestic legislation and policy initiatives by the individual governments involved, because there is no specific requirement for common policies, Malin pointed out.

"Until some further elaboration of other elements in the protocol has been agreed upon, however, governments will not be able to make determination of the potential economic impact of the protocol on their economies-thereby, it would seem, delaying consideration of a ratification strategy," he said. Malin also said that "the U.S. Senate resolved (unanimously) to not sign any treaty that excludes efforts by developing countries or that would harm the U.S. economy."

He noted that neither of these issues will be resolved quickly or easily, and certainly not by the next meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP-6) in fall 2000-a presidential election year in the U.S.

Other issues looming large for Kyoto implementation include:

- Compliance, especially the consequences of noncompliance. There is no mechanism for enforcing compliance and there won't be one until the protocol is ratified, leaving open the question of how readily parties will ratify it with a key provision left open to a future amendment process that calls for a second ratification.

- Credit for emissions cuts resulting from management of forest sinks and land use changes.

- Provision of funds and technology to developing countries by developed countries.

- Compensation to developing countries for damage to their economies from policies adopted by developed countries-notably the petroleum exporting countries.

- Constraints on the observer status of industry and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) at meetings of negotiating bodies.

Malin believes that the issue of potential climate change is a long-term challenge that should not be seen as an imminent crisis requiring immediate and dramatic action.

And, he contends, the treaty in its current form "has no meaning" because of the inevitable growth in projected CO2 emissions in developing countries.

"But industry must recognize society's concern over the issue and respond positively, including proactive participation in the public policy-making process," he said. "That, too, is our business."

Business opportunity

Seth Dunn, research associate with the Washington, D.C., NGO Worldwatch Institute, holds a view opposing those of Thorning and Malin regarding the immediacy of the climate change threat and the projections of the treaty's economic effects.

He noted that the U.S. managed to post economic growth of 2.5% in 1998 while effecting a 0.5% decline in carbon emissions, citing it as "evidence that there has been a start to the de-linking of carbon-based energy and economic growth." But he focused on the opportunities that lie ahead for oil companies that might emanate from Kyoto, seeing climate change initiatives as a major driver for oil companies' strategic and operational planning.

"Kyoto is an economic opportunity designed as an environmental agreement," he said.

Dunn estimated that new energy technologies would represent a $10 trillion market in 20 years. "Not surprisingly, the firms most proactive on the climate issue are those positioned to take advantage of the far-reaching energy transition-from a hydrocarbon economy to a renewable-hydrogen economy-that is getting under way."

Dunn contends that, regardless of near-term Kyoto Protocol ratification prospects, some governments and companies are likely to use the protocol and growing public concern over climate change as a wedge to further open up markets in carbon-free energy.

"As several key players are seeking to demonstrate, the post-Kyoto era presents major business opportunities for energy companies that are predominantly oil-based at present but that have the financial resources, foresight, and commitment to diversify into sources that will be increasingly important to the energy economy in the 21st century."