Iran seeks large volume of capital investment to boost upstream action

This article is adapted from the author's comments during a June 14-15, 1999, petroleum investment conference in Dubai, U.A.E. The views are his and do not necessarily represent the official position of CGES.

Objective commentary about Iran's oil and gas industry is difficult. One could get too enthusiastic about the achievements of the Islamic revolution since 1979 or be influenced by national pride.

Conversely, one could overemphasize the industry's setbacks caused by the disruptions from the revolution and by the war with Iraq during the 1980s. As an Iranian and a former National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC) employee, this task is even more difficult for me, but I will try my best.

To be fair, one has to acknowledge the setbacks-in particular, the severe physical damage from Iraq's air, missile, and artillery fire-as well as the departure of expatriate and some Iranian staff. More importantly, however, it should be noted that the industry also suffered from a shortage of investment, because the war efforts were naturally given greater priority.

For example, there was a need to procure weapons and ammunition for defending the country against Iraqi attacks, yet international sanctions made this task very complicated and, more importantly, extremely costly.

With the fall in the price of oil since the early 1980s and the country's much lower foreign exchange earnings, underinvestment in the oil industry could not be avoided. Currently, however, the investment requirements of the other sectors of Iran's economy are significant, and the oil sector always faces competition for scarce capital.

On the other hand, it is also fair to say that the underinvestment phenomenon is not limited to the Iranian oil industry but has been observed in many other countries that nationalized their oil industries a few decades ago and have not suffered from wars.

In these countries, the need for investment in the oil industry was not easily accepted in the years following nationalization. This was because, for decades before that, the oil sector had provided the country's treasury with revenues.

The oil sector was expected to continue acting as the cash cow. It was not always appreciated that the sector itself was in need of capital investment to maintain the level of oil production, let alone increase it.

Without sufficient investment, oil production declines. Following many years of underinvestment in these countries, the oil sector needs even greater capital to compensate for the years of neglect.

Similarly, one can generally criticize the nationalized oil industries in these countries for insufficient recruitment of technically qualified staff and poor personnel development over the years. However, such criticism would be unfair if stated out of context; in any case, it is not necessarily valid for all these countries. The oil sector has to compete with the other sectors of the domestic economy for absorbing a limited number of qualified people, many of whom leave the oil industry and follow careers in the country's private sector.

Salaries and benefits cannot be easily improved in a national company restricted by government regulations and remuneration ceilings.

Postwar output

It is fair to say that, in spite of all the difficulties, Iranian production did not cease after the revolution.

On the contrary, industry operations continued, and oil production averaged about 2 million b/d during the 8-year war with Iraq.

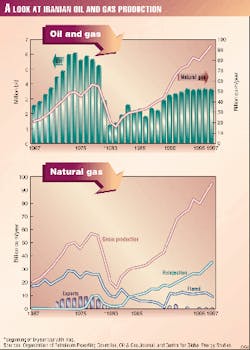

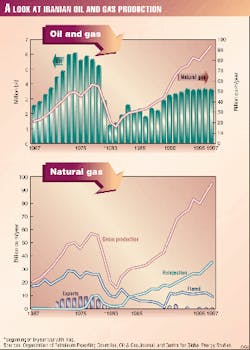

Iran's oil and gas production history is are shown in Fig. 1. There has been strong growth in gas production and injection and a reduction in of flaring in the last few years.

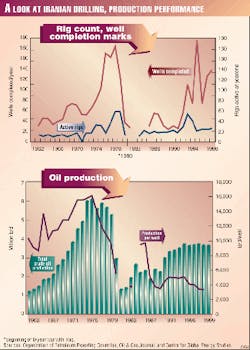

The drilling picture and oil production per well performance are shown in Fig 2. This figure demonstrates my comments on field activity requirements and also indicates the decline in production per well that had begun already in 1975. The latter underlines the need for an even more massive drilling program if the 6 million b/d production were to continue.

Nevertheless, the very impressive postrevolutionary performance record demonstrates Iran's many decades of oil industry experience.

In spite of the loss of staff caused by the revolution and the war, sufficient technical know-how still remained. With personal commitment of those who remained and worked under the dangerous conditions of the war, the industry survived, and one could even say that parts of it flourished.

A tremendous amount of experience was gained by the younger staff operating under these conditions over the war years, repeatedly carrying out speedy repairs of the facilities damaged by Iraqi attacks. Those who had retired or left the national company continued working as consultants and contractors. Iran came out of the war with a strong "private sector" serving the oil and gas industry-an invaluable asset for the country. At present, conventional oil-field operations can be competently carried out with domestic resources.

The two figures show that Iranian oil production increased to 3.5-4 million b/d soon after the cease-fire with Iraq, and gas production and utilization have also grown impressively.

In spite of this satisfactory performance, the petroleum industry's top management and policy-makers have been aware of Iran's shortcomings and limitations. These limitations are more noticeable when attempting a rapid increase in oil and gas production and a large-scale application of modern techniques.

The need for investment and new technology was widely recognized during the war years. The parliament approved the opening of Iran's industry to foreign investment in the form of the buy-back formula.

Production cutback

A comment is necessary about the new government's decision to reduce the country's oil production from 5.5-6 million b/d achieved in the mid-1970s to about 4 million b/d after the 1979 revolution.

Several reasons had been behind this policy decision, such as the concepts of conservation and keeping oil also for the future generations. These were popular concepts in the world at the time.

For example, the Dutch government had imposed limits on the production of gas from Groningen field.

However, it is worth noting that it would have been difficult to maintain the 6 million b/d production in the postrevolutionary environment.

Iranian production had grown consistently, increasing to 6 million b/d in 1973-74 from about 1 million b/d in 1960. During this period, many super-giant fields had been brought on stream. However, maintaining the 6 million b/d production would have required the continuation of field operations on a massive scale, with heavy annual expenditure and engaging a very large number of Iranian and expatriate professionals either directly employed by NIOC or on secondary assignments from international oil companies under the former oil service agreements.

Similarly, numerous oil service companies would have had to be engaged. The need for gas injection into the oil fields on an enormous and extensive scale is well known.

The drilling requirements would also have been immense. The number of wells drilled had been increased from 50-60/year in the early 1970s to about 160/year in 1976-77. This pace of drilling should have been maintained or even increased.

Buy-backs

Buy-back projects presented in London in July 1998 were not the first to be announced. Another seminar had been held in Tehran in autumn 1995, and an agreement with the U.S. firm Conoco Inc. had been reached before that in March 1995 but was soon canceled by U.S. presidential executive order.

The Conoco agreement had been preceded by a few years of negotiations with NIOC, gradually clarifying the terms of the buy-back agreement and satisfying the requirements of a private U.S. oil company, NIOC, the parliament's oil committee, the country's political organs, and the Islamic republic's constitution.

Progress in awarding buy-back projects has been slow. This is, however, natural and a consequence of the nature of buy-back agreements, the relative unfamiliarity of the international industry with this concept, the large number of buy-back projects to be negotiated at the technical and contractual levels, and the various U.S. sanctions.

Some of the buy-back projects are very large-scale, each requiring billions of dollars. Detailing such a contract cannot be carried out within a short period, irrespective of the international industry and NIOC experience with buy-back agreements.

The investment required for the 42 buy-back projects presented in London in July 1998 are much greater than the $5 billion or $6 billion mentioned during that conference.

For example, the Agha Jari project alone (a total of 20 tcf of gas to be injected into a depleted supergiant oil field) would require several billion dollars. It would also take many years to implement, and any oil production increase would be slow.

Last, it cannot be denied that the U.S. sanctions have contributed to the relatively slow pace of the buy-back deals announced so far. The sanctions have not only barred U.S. companies and reduced the competition among the applicants for buy-back projects but also made non-U.S. companies reconsider their positions, or, so to speak, drag their feet in spite of the questionable extraterritorial validity of the U.S. Congress's threat of imposing secondary sanctions on non-U.S. companies investing in Iran's oil and gas sector.

However, more and more non-U.S. firms have been ignoring the threat of sanctions and have concluded agreements with NIOC.

Politics, NIOC

The Iranian oil sector has always been under political influence.

The chief executives of NIOC were political personalities. NIOC's major national and international policy decisions were approved by the Shah, and matters relating to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries were under the minister of finance, again under the close guidance of the Shah.

However, it is worth remembering that two major events took place in Iran almost 20 years ago-the Islamic revolution in February 1979 and Iraq's military attack in September 1980, starting the Iran-Iraq war, which lasted until July 1988. These events made the 1980s a turning point for the country, its politics, social structure, ideology, and value system, and the population's awareness of and willingness to participate in public affairs.

Naturally, these events had profound influence on the management of the country's hydrocarbon industry. The point to be emphasized here is the growing importance of political considerations.

The revolution was preceded by turmoil, disturbances, street protests, demonstrations, and rapid government changes. The strike by oil industry workers was a major factor in these developments.

Also, it should not be forgotten that the hydrocarbon sector has been providing a major part of the country's foreign exchange earnings. About 74% of Iran's foreign exchange revenues in 1997 were derived from petroleum exports. It was thus expected that, following the success of the revolution, the industry would not remain immune from political interference.

The politicization of the petroleum industry was probably inevitable, though not desirable from the industry's point of view.

The war with Iraq made the politicization process even more widespread. It is worth remembering that some refineries and oil and gas fields became occupied by Iraqi military and the rest of the industry's installations were near the battle front.

Ministry established

The establishment of a ministry of petroleum after the revolution occurred not only to enable a petroleum minister to attend the OPEC ministerial conferences but also to establish a routine and more active presence of the hydrocarbon sector in the cabinet and the country's political scene. This was, and probably still is, justified.

Almost all other oil and gas producing countries in the world have a government department dealing with the overall oil policies at national and international levels.

For instance, the level of investment in the sector has to be compatible with the other sectors of the country's economy. A good example of this is Norway, which, with a small population, tried to avoid major fluctuations in the level of investment in the hydrocarbon sector.

Compared with the U.K., the Norwegian government has exerted much greater control over the activities of the hydrocarbon industry.

One result of this has been that, unlike the U.K., there has been a more or less smooth variation in the level of investment in Norway's oil and gas sector in the last 30 years.

Accordingly, oil production in the U.K. reached a peak of 2.67 million b/d in 1985, followed by a decline to 1.915 million b/d in 1990 and subsequent growth since then. This was in response to the decline in the price of oil in the early 1980s, its collapse in 1986, and its later recovery in 1987.

On the other hand, Norway's oil production growth continued smoothly since its commencement in the early 1970s. Modifying taxation and other government policies compensated for the price decline, securing the continuation of the investments in the oil sector.

The reverse happened in 1997-98, when the Norwegian government imposed a delay on starting a number of major oil and gas development projects in the country's offshore segment, a move designed to avoid overheating the Norwegian economy.

Awarding licenses for oil and gas exploration and development is also part of the government's responsibility of supervising industry activity and ascertaining the conservation and proper use of a country's oil and gas resources.

Postrevolution

After the revolution, most of the top management in Iran's oil, gas, and petrochemical companies were replaced. The new appointees, however, were chosen mostly on the basis of political considerations.

Gradually, however, the politicization process continued down to the lower levels of the organization and into the operational units. It is a trait of human nature to gather around the centers of power, especially during major changes and organizational rearrangement.

Individuals and groups try to fit themselves into the new ideologies or the new management style and corporate culture. Islamic and revolutionary credentials were given greater priority over technical competence and work experience. In this way, some of the industry's staff were promoted to much higher positions. This led to further departure of the technical staff.

As noted, one could argue that this was inevitable and was a natural consequence of the revolution and the 8-year war with Iraq. The country's other institutions and organizations also underwent a similar politicization after the revolution and during the war. Again, these can be explained as a natural consequence of the circumstances.

However, many of these, including the oil sector, have been modified since the cease-fire in 1988, and the country has reverted to peace conditions. Private companies have been established for various activities along the whole chain of exploration to development, production, transportation, and marketing in the domestic and international activities of oil, gas, petrochemicals, and related industries.

Nevertheless, one can argue that there is room for further depoliticization of the hydrocarbon industry to meet the changed requirements in a period of peace and reconstruction and to contribute to the country's development. Otherwise, as political institutions, they become battle grounds, with various political groups competing for power and influence.

The companies should become more efficient organizations, responsive to the needs of the time in a competitive international environment. They should be given greater authority and freedom of decision-making and operations but should also be responsible for achieving preset performance targets.

The ministry should be organizationally separated from NIOC, National Iranian Gas Co., National Iranian Petrochemical Industries Co., and other affiliated companies.

Of course, the overall policies of these companies, such as long-term strategy, growth objectives in the domestic and international arena, and the level of investment, and the decision on allowing foreign participation and its extent, should be approved by the ministry. Similarly, the geographic location of domestic activities should be coordinated with the country's economic and development goals.

The ministry does play such a role for the petroleum industry.

However, this high-level policy guidance and approval should not be extended too far down the organization. Operations and project management should be carried out by professionals and not by politicians.

The Author

Manouchehr Takin is a senior petroleum pstream analyst with London's Centre for Global Energy Studies. Before joining CGES in 1990, he spent 9 years as a senior research officer at the OPEC Secretariat, analyzing global energy and oil markets. He has 18 years of experience in the oil industry and served as acting head of exploration-production research at National Iranian Oil Co. and as exploration manager with the former Ultramar Corp. He has a BS Honors degree in geology from Manchester University, an MBA from the Industrial Management Institute, Tehran, and a PhD in geophysics from Cambridge University.