Italy's gas sector poised for boom once deregulation hurdles cleared

Deregulation of Italy's natural gas and electricity sectors is setting the stage for a major expansion of that country's gas industry and a transformation of its energy sector as "BTU convergence" continues to spread around the world.

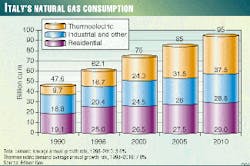

Italy's gas demand is projected to increase from the current level of 62 billion cu m (bcm)/year-making it the third largest market in Europe after Germany and the U.K.-to 80 bcm/ year in 2005 and 100 bcm/year in 2015 (Fig. 1).

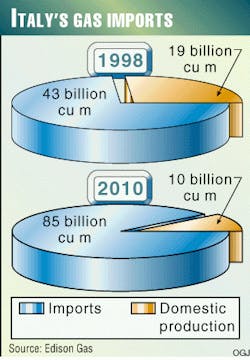

Italian imports of gas are expected to account for 90% of the market in that same time frame (Fig. 2).

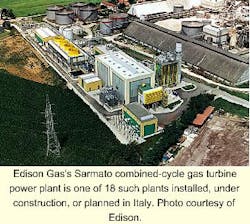

This sizzling projected gas demand growth rate-matched in Europe only by the U.K. and Spain-is spurred mainly by the proliferation of natural gas-fired combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) and cogeneration power plants. In addition, plans are under way to establish natural gas grids on the island of Sardinia and other key areas of the Mediterranean within Italy's sphere of influence.

The deregulation of the electrical sector is also allowing such oil and gas companies as Edison SpA, Sondel SpA, and Isab SpA to evolve into integrated energy companies.

Meanwhile, the former state-owned electric monopoly ENEL will sell 15,000 MW of its power capacity and is making its own plans to enter into the gas distribution business.

Snam SpA, gas market leader and unit of the state energy conglomerate ENI, is fighting hard to keep control of its 27,000-km Italian gas pipeline network while at the same time trying to enter new markets in Turkey and Portugal.

Italian legislation

Italy's current energy industry restructuring began with the 98/30 European Union directive deregulating gas markets, which will take effect Aug. 6, 2000. It is intended to create a competitive European market for natural gas by establishing free markets in each nation. The directive imposes common rules for the natural gas market within the EU.

Most importantly, the directive calls for third-party access to national gas networks by "suitable" customers. It asks for unbundling of prices by the pipeline owner and seeks to define "objective and non-discriminatory criteria" for laying and managing pipelines.

To translate the EU directive into a national law, the Italian parliament issued on May 17 a parliamentary bill that outlines the gas deregulation initiative. The Italian government has 9 months to publish a final decree if effective implementation is to meet the EU deadline.

Meanwhile, companies are lobbying to see their needs reflected in the decree, and the Italian Electricity and Gas Authority (EGA), the industry watchdog together with the Antitrust Authority, has expressed some concerns: "The government has wide margins of decision," EGA said. "However, the monopoly of ENI is very strong. What's more, ENI has become (partly) the property of private shareholders, so the state can't intervene directly, as in the case of the electrical sector."

EGA says that means the state cannot disincorporate ENI for fear of lowering the value of its shares. In the case of electricity, transmission will be entrusted to a separate company; but in the case of gas, the parliamentary bill says "that integrated companies should (create) separate companies... only (when) it contributes to the development of the market," said EGA, which described that rule as "restrictive."

Yet the pressure is mounting for the Italian government to sort out the competing interests on the path to deregulation. According to Pippo Ranci, the chairman of EGA: "Not only is the price of (Italian) gas (including taxes) the highest in Europe, but it is also higher by 5% or more than the average European price, without taxes." This price disparity is also reflected in a loss of competitiveness for energy-intensive Italian industries, EGA noted.

Price unbundling and regulated tariffs for pipeline system access will probably be the main tools of the Italian deregulation approach. The parliamentary bill seeks "to warrant clear prices and non-discriminatory conditions for regulated access to the gas system," EGA noted. "So far, prices have (comprised) the different elements that constitute the cost of supply: primary transportation, storage and modulation, (and) distribution and sale, without the possibility of checking the adequacy of price to cost."

Instead, the parliamentary bill requires that "Gas companies must keep separate internal accounts for their import, transportation, distribution, and storage activities...in order to avoid discrimination or distortion of competition."

Monopoly status

It remains to be seen if such approaches to deregulation will work in a market as heavily monopoly-oriented as Italy's.

According to EGA, "The Italian market is very concentrated in supply and transportation and very fragmented in distribution, where local monopoly conditions prevail...In all stages, service is dominated by ENI and its subsidiaries: 90% of domestic production is (operated) by Agip SpA, while 91% of (Italy's gas) imports are made by Snam, which also owns 96% of the high and low-pressure (pipeline) networks. Through Agip, ENI also owns almost all the storage capacity (in Italy)...Even in distribution, ENI owns 41% of the stock of the biggest retailer, Italgas, and owns substantial shares of 10 distribution companies that (account for) 30% of Italian sales."

The distribution market is extremely fragmented: of a total of 735 Italian distribution companies, 30 supply over 100 million cu m/year and 100 supply at least 50 million cu m/year. EGA said, "The directive could help start a process of consolidation for the small municipal concerns that can form combines to become 'suitable customers' (for third-party access) and thus become more efficient and cost-effective."

But this will happen only if "distributors will open their networks to third parties, wanting to sell to 'suitable customers' through their urban networks." According to the EU directive, the initial 20% share of a country's gas market that is free in 2000 must increase to 28% by 2005 and 33% by 2010.

Among those defined as "suitable customers" are electricity producers, including cogenerators, and all customers with gas demand averaging more than 25 million cu m/year. They will be able to choose their gas supplier and have free access to transmission and distribution networks. The threshold for suitability is to be lowered to 15 million cu m/year by 2005 and 5 million cu m/year by 2010.

However, in Italy, 70% of industrial- sector gas demand comes from mid-sized to small concerns that don't use even as much as 5 million cu m/year each. EGA proposes to lower the national threshold below the European one and to recognize aggregated buying of gas by industrial consortiums.

EGA wants to take the process a step further in order to allow fair access to the national grid by such entities. Pippo Ranci, at a parliamentary hearing on Mar. 24, said, "Price unbundling is necessary to see clearly if there are no subsidies that could damage a customer or an operator to the advantage of another...Unbundling of companies is stronger: It erects a higher barrier against these types of distortions and manipulations and therefore can be useful when fear of these distortions is great."

Competition concerns

While awaiting the new rules of the game, the Antitrust Authority has already waged its own campaign for a freer market.

According to Ranci, Snam was fined by the Antitrust Authority 3.5 billion lira for abuse of dominant market position to the detriment of Edison Gas. However, in another such case, the Antitrust Authority was overruled by the Regional Court of Lazio on May 26.

On the domestic production side, competition has been almost nonexistent. Domestic production of natural gas in 1998 at 19.8 bcm/year covered one third of domestic demand. Agip, with 16.8 bcm/year, is the main producer with a 90% market share, followed by Edison Gas at 1.5 bcm/year, while the remainder, 0.6 bcm/year, is produced by Elf Aquitaine SA, TotalFina SA, and others.

Italy's imports of natural gas totaled 39 bcm/year in 1998, or 67% of total demand, and are expected to increase as domestic production continues to decline. The top suppliers are Algeria (19.8 bcm/year), Russia (16.7 bcm/ year), and the Netherlands (3 bcm/ year), soon to be joined by Norway and Libya.

According to EGA, imports could almost double in 10 years. To meet the explosive growth in demand, Snam signed a series of long-term contracts during 1995-98. Dutch supplies under contract have jumped to 10 bcm/year from 5 bcm/year, while another 8 bcm/year from Russia has been booked, and negotiations are under way with Libya for 8 bcm/year and Norway for 6 bcm/year, all via pipe- line.

ENEL is the other big importer. Since 1996, it has been buying 4 bcm/year of gas from Algeria via the Transmed pipeline under a contract due to expire in 2017. Beginning this year, ENEL started receiving shipments of LNG from Nigeria at a volume of 3.5 bcm/year for the next 22.5 years. ENEL had planned to build its own new LNG regasification infrastructure at Monfalcone but, after environmental disputes, decided to ask Gaz de France to use its Montoir terminal in southern France.

All these are take-or-pay contracts that tend to saturate the capacity of the Italian infrastructure, thus acting as de facto barriers to market entry. At the March parliamentary session, EGA's Ranci said, "It seems that other contracts signed by ENEL, Edison, and other operators (than ENI) will cover 15% of the market in 2003. Probably the room for competition will be limited by the saturation of the (present) network of gas pipelines...(or expanded) by new investments in regasification terminals and eventually in pipelines." Ranci also voiced concern that gas pipeline operators being tied to take-or-pay contracts might crowd out other entrants into the pipeline sector.

ENI claims that its pipelines are already open to the competition, citing Snam's transportation in 1997 of 8.1 bcm for third parties, including ENEL's gas from Algeria (2.4 bcm), Edison, and Slovenia's state gas company. In the present public debate about deregulation, ENI has kept a very low profile. In a comment on the EU gas directive, the company insisted that its past investments in the national gas network must be protected: "The transportation structures are imposing and costly; they are dedicated and not reconvertible." It has also publicly argued that its negotiating powers have so far assured competitive prices, but it warns that prices could be affected by too-sudden deregulation: "The implicit risk is that the rise in efficiency, determined by competition, would be offset by the strengthening of the dominant position of producing countries (that are not subjected to European legislation), therefore increasing gas import prices. Moreover, a deregulated system could induce in dominant producers strategies that would limit, instead of stimulate, the diversification of supply sources.ellipse"

Snam also insists that reciprocity clauses in the European directive "...must ensure a balance, not so much among operators in the same country but among European operators."

Edison Gas plans

Meanwhile, Edison Gas has quickly seized upon the new opportunities that deregulation offers.

It aims to increase its share of the Italian market to 10% from 3% and to build new infrastructure in Italy (Fig. 3a). Edison has stepped up significantly its exploration investments in Egypt, which have led to a sharp increase in the company's gas reserves. Edison's reserves jumped from 49 bcm at the start of 1998 (24.9 bcm in Egypt, 23 bcm in Italy, and 0.3 bcm in the U.K. North Sea) to 70-80 bcm, thanks to a string of huge discoveries in Egypt.

Giulio Paini, managing director of Edison Gas, said, "We think that global demand in Italy in 2010 will be 95 bcm/year. Edison is set to supply 10 bcm/year...by 2010 vs. our present 2 bcm in 1999. Of these, 5 bcm are our own additional needs for thermoelectric power, (so) another 5 is a rather conservative target. To this purpose, we have a series of projects. We are buying spot LNG from Abu Dhabi, Qatar, and Algeria and carrying it to Snam's Panigaglia terminal in northern Italy. We also have a project to build an LNG offshore terminal in the North Adriatic near Rovigo with a capacity of 4 bcm/year (Fig. 3b). The technical committee of the region gave its green light, and we believe it will become operative by 2003."

On Apr. 23, 1999, Edison signed a contract with In Salah Gas, a joint venture of Algerian state petroleum company Sonatrach and BP Amoco plc, for supply of 4 bcm/year for 15 years beginning in 2003: "The imports from In Salah at the moment would be carried by the residual capacity of Transmed, which has already been doubled and has a capacity of 24 bcm/year, which is not totally used. Additional capacity can be obtained, by adding a compression station, of 6 bcm/year," Paini said.

Alternatively, if for some reason the Snam-operated Transmed line could not be accessed, Edison could build a pipeline from Algeria to Sardinia, Corsica, and Italy. "It would have the double advantage of being a new transportation axis from North Africa, which wants to increase its exports, and supplying Sardinia, which ardently desires natural gas," Paini said. "A 1.5 bcm/year demand would be a likely figure for supplying both Sardinia and Corsica."

The Italian government has already approved capital investment, and construction of the Sardinian network is to begin in 2001. Edison is in early talks with the government and soon will be with the regional authorities.

Edison realizes that it would cost less to tie Sardinia to the existing Snam network on the continent. However, Paini pointed out, "It's not only Sardinia. The line we have in mind could carry 8.5 bcm. We think of it as an axis comparable to Transmed that could carry gas from Algeria to Italy and possibly to the south of France.

There is a third alternative: a pipeline from Libya to Italy that ENI has proposed.

"These three projects should be sorted out," Paini said. "Expansion of Transmed has the advantage of low costs. Our project, instead, solves the problem of Sardinia and creates a new market."

Edison's concerns

But effective deregulation is important for Edison's plans. "According to the parliamentary bill, the transportation tariffs must be defined by the authority (EGA) and must be made public," Paini said. "We understand that the government has accepted this. This is important to establish a climate of competition, so that new operators won't be discriminated against. But it is also important that the management of the Italian transportation network be given to a new company that controls some segments of foreign pipelines. The real problem is that Snam is controlling all the supply lines of the market: the pipeline from Austria, carrying Russian gas; the pipeline via Switzerland, carrying Dutch gas and Norwegian gas in the future; and the Transmed to Sicily, carrying Algerian gas. Now it is useless to create a plurality of 'suitable' customers, as the European directive does, if there is no plurality of suppliers.

"We would rather see a separate company that not only manages the domestic infrastructure but also controls the big import lines and provides access under non-discriminatory conditions. Otherwise, the possibilities for a market to develop are extremely small. Instead, a separate company that has an aim to sell services will be interested in having the maximum number of customers."

Control of storage facilities is also a strategic issue, Paini noted: "Storage is important insofar that export-import volumes travel in fixed quantites. Storage is used to match a constant supply with enormously varying seasonal demand. If you don't have storage, you cannot reach customers with suitable services. We have two storage units, and we are enlarging the second (Conegliano). Yet we think that the storage capacity in Italy should be made available to new entrants at non-discriminatory conditions." At present, ENI, through Agip, owns 28 bcm of storage capacity vs. 0.1 bcm for Edison.

Another fact that has bogged down competition is the "public utility" tag that the government has applied to former state-owned company infrastructure. This enabled speedy expropriation of land for laying pipelines. But the question has arisen as to whether this public utility tag should apply to new infrastructure built by new market entrants: "Yes, absolutely," Paini said. "There has always been discrimination in favor of the state company. Now this has to be eliminated, (but) the building of new infrastructure is fundamental for the development of the market."

According to the parliamentary bill, the "public utility" tag should be extended to all gas infrastructure built by any entrant.

Egyptian strategy

While it awaits the outcome of domestic deregulation efforts, Edison has turned its sights to foreign supply sources, notably spectacular exploratory successes off Egypt, where Edison participates in four gas permits.

During recent production tests of the Wddm-5 (West Delta Deep) discovery well off Alexandria, which is owned 50-50 by Edison and BG plc, the companies gauged a flow rate of 1.5 million cu m/day.

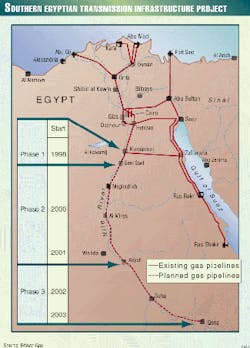

However, Egypt's market won't be able to absorb the level of gas volumes predicted to be produced from the offshore strikes. Indeed, in 1999, Edison, BG, and local partners established the Nile Valley Gas Co. to build a 600-km pipeline from Beni Suef to Quena, with an optional spur to Aswan for another 270 km (Fig. 4). This will enable Egypt to substitute gas for oil for domestic consumption and allow the country to export the oil, says Edison. But even at that, the Egyptian supplies still will outstrip domestic demand and thus must seek export markets.

Edison is considering an LNG regasification terminal in the northern Adriatic. Another alternative is to feed the burgeoning Turkish market. Paini said, "We are analyzing the possibility of building a liquefaction plant in Egypt, which should export gas from the southern Mediterranean area. Turkey is the closest and most likely customer. Izmir (Turkey) is a good candidate for an LNG project because they are far away from the main pipelines. As for quantities to ship from Egypt, we are thinking about beginning with 4 bcm/year, which might later be doubled."

Integrated energy companies

The privatization of the electrical sector in Italy is spurring gas producers such as Edison to carve themselves a big slice of the electrical market by way of CCGT and cogeneration projects.

Industrial consumption of gas in Italy totals 21.9 bcm (three-fourths of which is supplied by Snam); of this total, thermoelectric power demand accounts for 15.5 bcm (of which 10.5 bcm is supplied by Snam, 4 bcm by ENEL, and 1.0 bcm by Edison and other private companies).

Paini said, "Originally, we were an exploration and production company, but now that we are also producing electricity, we have integrated the two activities through CCGT technology. We have 12 CCGT plants installed, 3 being built, and another 3 projected. We have 3,500 MW (of capacity) installed, another 600 MW being built, and a further 300 MW projected, all CCGT."

With this strategy, Edison is both a competitor and an ally of Snam. It recently announced it will build a 340-MW gas turbine power plant in partnership with ENI at Foggia, in southern Italy, although Edison will be the majority partner. On June 3, it launched a joint venture with Milan's public utilities distributor AEM to build at Settimo Torinese (Turin) a 100-MW CCGT unit that is upgradable to 250 MW.

In the Colleferro industrial area of Rome, Edison has signed an agreement with Italcementi to provide its two cement plants at Vibo Valentia and Sarno in southern Italy with 100 million kw-hr/year of power. Edison will also provide about 36 million kw-hr/year to Consorzio Elettra, grouping seven enterprises in northern Italy.

On July 6, Edison unveiled plans for a new 140-MW CCGT power station near Piacenza that will serve an industrial consortium. Edison also is expanding capacity at its Marghera Levante power plant by 180 MW while building new cogeneration and combined cycle plants at Piombino (180 MW) and Terni (100 MW), respectively.

Edison is also interested in buying some of the 15,000 MW of power capacity that ENEL must relinquish.

Edison is not the only company interested in the sale of ENEL's 15,000 MW of capacity. Anonima Petroli Italiana SpA Chairman Aldo Brachetti Peretti said that his group is also interested in some of the power plants that ENEL will sell. Sondel Chairman Achille Colombo, whose company produces 600 MW of cogeneration power, also expressed an interest in buying capacity from ENEL and ACEA, Rome's public electric utility.

Edison also plans to increase its 6% stake in AEM, a big public utility company that distributes electricity to Milan and Turin and that could offer gas as well. Edison also bought Societa Adriatica Gas and will buy interests in ACEA, which is beginning to undergo privatization.

"We have a 'fuel-to-market strategy,'" said Edison's Paini. "Our strategy is to get as close as possible to the end user, and we are very interested in public utilities." Edison's target is to boost its customer base to 300,000 from the current level of 60,000. "Since Edison has control on the main cost factor, which is gas, it will have the best margins, both as an electricity and a gas distributor," he said.

So far, each public utility company has been allowed to decide how to privatize and what percentage of shares it will offer. For instance, AEM has begun offering interests for sale totaling 6%, but that is due to increase next year. It could also buy ENEL's share of the Milan market. ACEA, in which shares are being floated now, said it will offer up to 49%.

There is no danger, however, that entire cities will be held at ransom by private companies under the new regime-a concern that led the parliament to debate the 40/14 bill, which would establish operating standards for licenses and would impose cyclical renewals, possibly every 10 years. Any license, public or private, will be submitted to a tender.

The next challenge for Italian energy utilities is the prospect faced by utilities in the U.S. and elsewhere in Europe that are already in the midst of the BTU convergence trend: how to operate different types of utility services in a market rapidly becoming more deregulated.

Nerio Negrini of Federgasacqua, one of the two main public utilities associations, noted, "Network services have common mechanisms: how you relate to customers, how you bill them. You can obtain appreciable synergies from the integration of services, as Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands discovered long ago."

Public utilities' concerns

So far, the deregulation of the electrical sector has led the way, but debate among regulators, producers, and distributors over gas deregulation will heat up this winter.

Federgasacqua is an association of public utilities that aggregates 17 million customers in Milan, Genova, Trieste, Bologna, Reggio Emilia, Bari, Palermo, and Catania-about 40% of the Italian market. The other main utilities association in Italy is Anigas, of which ENI's Italgas-with 33% of the market-is a member.

Federgasacqua's Negrini said, "If distributors will be able to buy their gas directly, there will be more room for reducing the (burnertip) prices of natural gas. But we don't know yet if public utilities will be considered as 'suitable customers' by the government. Basically, there are two problems. One is that Snam has made it known that 96% of its contracts are of the take-or-pay kind. Now, the initial share of the market to be opened to competition by the European directive is 20%. If municipal and other public utilities were to be considered suitable, this 20% will be exceeded in Italy, and the take-or-pay contracts would be endangered."

Indeed, in a public hearing to parliament, Snam testified that its contracts leave 20% of the Italian market open to competition by 2003.

"The other problem is bilateral agreements," Negrini said. "At the moment, France refuses network access to third parties, and this might trigger a clause in the directive that suspends the opening of the market. Big companies such as Gaz de France, Snam, and (Germany's) Ruhrgas AG will step down from their dominant position in their respective countries only if they are given the chance to compete in other European countries."

Nevertheless, Federgasacqua has asked the government to have its members be recognized as "suitable customers."

"We want this, because we think we'll get better prices from the market. But, so far, the EU directive applies only to electricity producers and big industrial users," said Negrini. "Now we represent more than 100 companies that are above the 25 million cu m/year threshold, yet not one can lawfully access the free market. Nor are we allowed to make consortia. What is possible in the electrical sector is not in the gas one. It makes no sense at all. If we compare the Italian market for gas with other European countries, we see that Italy is penalized by a much higher cost of raw material, while the distribution cost is comparable. The price of gas paid to Snam by public utilities companies is 40-50% higher than that paid by industrial customers. It is true that gas demand for households is strongly seasonalized, so that it is more expensive to deliver. But apart from that, the real problem is that we cannot negotiate more than that, because we can't go to another big European operator and ask for their prices."

So far, prices have been negotiated between parties under the auspices of the Ministry of Industry. Now tariffs are delegated to the EGA; but, Snam maintains that the authority has no right to regulate prices, because Snam says that it operates on a free market.

"It's nonsense, of course," said Negrini, referring to Snam's stance. "It would be a free market only if there were other suppliers."

Negrini says the standoff can be ended "ellipseby defining indemnity criteria for take-or-pay contracts and by unbundling costs of transportation and storage, instead of accepting Snam's line that it operates on a free market in order to be able to ask fearful prices. This is the meaning of 'regulated access' that the parliamentary bill asks for. However, the EGA has queried officially the parliament and the government if it is entitled to regulate those prices but without getting an answer so far."

Strategic supplies

According to observers in the gas industry, the main obstacle for deregulation is that the government fears for strategic supplies in a country that depends heavily on imports.

ENI's companies have been able to ensure oil and gas supplies through every energy crisis-lately in Algeria, where a pipeline was attacked by terrorists a few months ago but the outage lasted only 4 days.

So far, ENI's foresight and diplomacy have ensured a measure of calm. But the Ministry of Industry fears that opening Italy's market to new gas importers from unstable countries carries a heavy sociopolitical risk. EGA takes another view: It believes in building more LNG terminals to diversify sources, but after the debacle over the Monfalcone LNG terminal, this stance seems overly optimistic.

Perhaps the success of the new Edison LNG offshore terminal in the Adriatic or the proposal of the Algeria-Sardinia pipeline will allay some of those fears. Public utilities are also ready to invest, Negrini noted: "We have big companies that are available to build new terminals and infrastructure. We are already building some transportation capacity."

In the short term, regulated access to the national network, and, in the long term, the construction of alternative infrastructure might be the tandem key to unleashing the potential of the Italian gas market.