Brazil's Three Natural Gas Systems: Sources, Markets, Regulations, And Business Perspectives

After 50 years of state monopoly on oil and gas activities and of a secondary role for natural gas in the country`s energy mix, Brazil has finally started looking seriously at natural gas as a important alternative source of energy to help match expected rising demand.

Brazilian exploration and production efforts now target natural gas, pipeline projects proliferate throughout the nation`s territory, markets start to become a tangible reality, and regulations are expected to be modern and flexible. Apart from the well-known Bolivia-to-Brazil (BTB) pipeline, other important projects are gaining importance, such as developing the Northeast Brazil market and the Argentina-Brazil gas supply connection-not to forget the old dream of bring viability to the Amazon region gas reserves.

The new scenario for natural gas activities in Brazil is still under construction. However, it already gives positive signs to both investors and consumers. The perspectives are therefore extremely interesting.

This article defines, for the first time, three distinct natural gas systems within Brazil, pointing out the basic characteristics and indicators for each of them. It also outlines the approach that has been taken by the Brazilian government through its National Petroleum Agency (ANP) to regulate the natural gas sector in Brazil aiming at building a competitive market, with sound infrastructure and integrated with the other relevant systems with South America.

Brazil gas industry history

The development of Brazil`s natural gas industry only very recently emerged as a governmental concern of national scope.

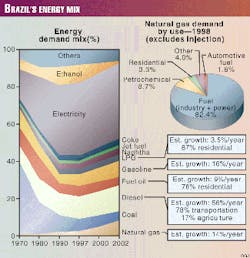

Historically, the share of natural gas in Brazil`s energy mix never has reached more than 3% of the country`s total energy consumption. Although it has become common to say that this was due to the lack of supply in the country, this is only part of the story. The truth is that the national oil company, Petroleo Brasileiro SA (Petrobras), never paid much attention to the country`s natural gas potential. Instead, it concentrated all of its efforts on the development of crude oil and its fuel products. Moreover, before 1986, there was a complete lack of governmental directives concerning the promotion of natural gas use among all the other energy sources available in Brazil.1 Fig. 1 shows a simplified sketch of the historic evolution of Brazil`s energy mix, highlighting natural gas.

The theory and experience of natural gas markets in Brazil are, by consequence, also very recent and yet preliminary. An eloquent example is given by the following fact: Only since 1987 Petrobras has commercially supplied natural gas to Sao Paulo, a market currently touted as the potential heart of natural gas consumption in South America.

In fact, the actual use of natural gas in Brazil-apart from the mere reinjection in conventional oil fields in the Recôncavo, Sergipe-Alagoas, and Potiguar basins of northeastern Brazil-began in 1974 with the major discoveries in the Campos basin off Rio de Janeiro. Also, associated gas started to be used in gas turbines for power generation on the Campos offshore platforms. However, these uses were negligible.

In 1983, Petrobras built its first major gas pipeline. The Nordestao pipeline linking the Guamar´ Terminal in Rio Grande do Norte state to the city of Cabo, near Recife, Pernambuco, with branches to Natal, Rio Grande do Norte; Campina Grande, Pernambuco; and other main cities of the Northeast.

In 1984-85, two other gas pipelines were completed in the state of Rio de Janeiro: the first connects the Cabi&#pound;nas terminal-which receives production from the offshore Campos basin-to Rio de Janeiro, with an extension to the Duque de Caxias Refinery (Reduc); the second takes incoming natural gas from Rio de Janeiro further down to the CSN steel mills in the city of Volta Redonda, Rio de Janeiro state. During 1985-86, various pipeline spurs were also built in the states of Pernambuco and Rio de Janeiro mainly to supply local industries.

In 1986, as a result of the discovery of the Merluza gas field in the Santos basin off Sao Paulo state and the strong environmental concerns regarding the industrial city of Cubatao (an urban area then measured as having the world`s most polluted air), natural gas started to be seen as a viable and cleaner alternative source of energy in the eyes of Sao Paulo`s industrialists.

Although by this time natural gas coming from Brazilian fields was already being used as fuel (methane) or in the production of ammonium, urea, methanol, and fertilizers, the announcement in 1996 of a final agreement for the construction of the BTB pipeline accelerated interest in the development of natural gas in Brazil. However, there were still some roadblocks. Although the pipeline idea had already consumed 40 years of strategic essays, technical studies, and official negotiations between the two governments, the privatization of the Bolivian state oil company YPFB and Brazil`s constitutional reforms led to many debates and uncertainties regarding the future of natural gas in Brazil. Today, now that the pipeline has reached Sao Paulo, major changes in the region`s configuration are expected, and integration among the Southern Cone countries tends to be consolidated faster in relation to natural gas logistics than probably in any other commercial field. Therefore, natural gas may soon become a backbone of this regional integration process.

Nevertheless, major natural gas initiatives expected to result from the start-up of the BTB pipeline could be dampened by Brazil`s lack of tradition in regulating natural gas markets and its inexperience in establishing contracts for transportation, purchase, and distribution. This area has proven to be a sensitive one for the main current players.

Although in Brazil, natural gas consumption is still in its infancy at 10.6 million cu m/day, estimates are that it is likely to grow to above 35 million cu m day over the next 10 years.2 Demand is expected to be driven mainly by the industrial sector and by the new gas-fired thermal power plants. Given that the country`s electricity demand is expected to increase at an annual rate of 5% and that there is a lack of sufficient hydroelectric projects to meet this demand, these plants would provide a viable alternative. Apart from the aforementioned uses, new processing capacity coming on stream will allow third-generation industries to use natural gas by-products as feedstocks for petrochemical plants producing plastic packaging materials, etc. New ethylene and polyethylene plants in Rio de Janeiro and a glass and chemical complex in Natal will use natural gas coming from the Campos and Potiguar basins, respectively.

After having neglected the possibility of employing natural gas as a significant, cheap, and clean source of energy for so many years, Brazil finally expects to quickly see the results of its major efforts to expand the share of natural gas in its energy mix. The BTB pipeline is expected to transform the energy mix of Brazil. Today, natural gas is the 12th largest energy source in Brazil, less than half the level of wood on an energy-equivalent basis. The future direction of Brazil`s energy consumption should raise the gas market share from the current 2% to almost 8% by 2000 and more than 14% by 20103 . Electricity generation and industrial use will certainly drive the demand growth, as Brazil does not have the infrastructure for residential gas demand. The temperate climate in the great majority of the national territory restricts residential use for natural gas to cooking and boilers, which also does not creates significant scale for installing distribution networks in the concentrated, urban coastal cities. This reality could change with the introduction of new technologies for other residential uses of natural gas.

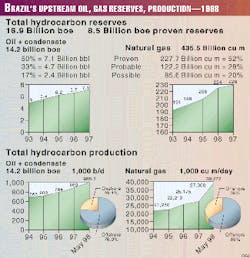

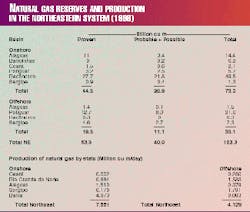

As it is well known, the monopoly gas supplier and transporter in Brazil until 1996 was Petrobras. Following the progressive opening up of the petroleum industry in Brazil, Petrobras is expected to share the market with private investors. Brazil`s current reserves and production figures are shown in Fig. 2.

Current production of natural gas in Brazil is about 40 million cu m/day, about 41% of which is sold commercially. In certain areas where transportation is a limiting factor, such as in the Amazon, the majority of the gas produced is reinjected (about 1 million cu m/day).

To better understand the current operational framework and its future developments both strategically and physically, one must look at Brazil`s three major natural gas systems, which are detailed in the following sections.

Southeast-South system

The Southeast-South system can be defined as the natural gas reserves and pipelines designed to supply and interconnect the major and secondary consuming centers of the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso do Sul, Sao Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. A possible expanded version of this system could be considered by adding the Rio de Janeiro, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais subsystem, mainly supplied by the gas coming from the Campos, Santos, and Espírito Santo offshore basins. To the northwest of this same major system, three other main states may be soon incorporated: Mato Grosso, Goiás, and the Federal District (DF), home to the nation`s capital, Brasília.

To better illustrate the importance of Brazil`s Southeast and South regions within the country`s economy and demographics, Table 1 provides the most relevant regional indicators and their proportion compared with the national figures.

The primary sources for this system are the natural gas reserves of central and southern Bolivia and northern Argentina to the west and the offshore reserves of the Campos, Santos, and Espírito Santo producing basins. The main consuming centers are the cities of Corumbá, Campo Grande (thermal plants), Campinas, Sao Paulo, Curitiba, Joinville, Itajaí, Florianopolis, Criciúma and Porto Alegre (industries and thermal plants) alongside the BTB pipeline. Vitória, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte (industries, residential, and thermal plants) are already connected by an efficient network of pipelines. Alegrete and Uruguaiana (thermal plants), expected to receive Argentine gas through new pipelines yet to be built, are also important centers to be considered. An incredibly fast expansion of local distribution networks is under implementation within such states as Sao Paulo, Mato Grosso do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Rio Grande do Sul. These states have formed natural gas distribution companies from scratch during the last 2 years.

The greatest increase in Brazil`s natural gas use is expected to come from this region as a result of increasing gas production in Brazilian basins, combined with the new sources of supply coming from Bolivia and Argentina.

Campos, Santos basins

The major and primary domestic producing region for natural gas in Brazil is the Campos basin, supplying around 7 million cu m/day to markets in Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo, which also receive gas from Merluza field in the Santos basin.

Campos gas reaches the shore at the Cabiónas terminal, connected to the Reduc refinery (Rio de Janeiro) by a 16-in., 178-km gas pipeline. A relatively simple system of two main gas pipelines are then responsible for the transportation to the other regional markets: 425-km Gaspal, linking Reduc refinery to Volta Redonda in Rio de Janeiro state (18 in., 100 km) and farther to Sao Paulo (22 in., 325 km). Along the Rio-Sao Paulo axis, many industrial and commercial consumers started proliferating, spurring the installation of city gates and distribution subsystems in intermediate cities such as Caçapava, Sao José, dos Campos, and Jacareí. Today, Gaspal supplies more than 4 million cu m/day of gas to the state of Sao Paulo (Comgás) and the Paraíba River Valley in Rio de Janeiro state. This line is soon expected to attain its maximum capacity of 5.2 million cu m/day. Consequently, either a loop in the Rio-Volta Redonda line or two compression stations at Volta Redonda and Lorena, Sao Paulo, could be built as a solution for this capacity problem.

Gasbel is the second main arm of the Southeast system, connecting the Reduc refinery to Belo Horizonte in Minas Gerais state. This 16-in., 360-km pipeline has an intermediate city gate at Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, and capacity to transport only 400,000 cu m/day of gas.

In March 1999, with the start-up of the BTB pipeline, the state of Sao Paulo was receiving a total of 8 million cu m/day of natural gas via pipeline, of which 4 million cu m/day is Bolivian natural gas.

According to the head of Petrobras`s natural gas division, Paulo Roberto Costa, the future configuration of the industrial and power generation demands for natural gas in the region will be decisive in shaping the future logistics for the sector in Southeast Brazil. As both BTB and Gasbel are reversible, there is great flexibility for future switches in flow direction. Even Gaspal may be reversed in case demand in Rio, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais states increases and the Santos basin becomes a second major gas domestic source. Today, nonassociated gas produced from Merluza field supplies mainly the Santos and Cubatao industrial areas with 1.5 million cu m/day and occasionally functions as a backup for Sao Paulo and other cities in the state. On these occasions, Merluza`s overall supplies may reach 2.3 million cu m/day.

Espírito Santo subsystem

Apart from the Brazilian reserves in the Campos and Santos basins, it is also relevant to mention the subsystem of Espírito Santo, within the Southeast-South system.

Today, natural gas markets in the state of Espírito Santo (mainly the cities of Vitória, Vila Velha, and Tubarao) are supplied by reserves located in the onshore and offshore Espírito Santo basin. A gas pipeline connects the producing region of Lagoa Parda and the offshore fields with Vitória. This subsystem is projected to be connected to the Campos-Santos subsystem through a new 20-in., 325-km gas pipeline linking the Cabiúnas terminal to Vitória, which will thereby receive 4 million cu m/day of natural gas.

Brazilian major mining company CVRD plans to use natural gas for power generation in its facilities in Vitória. CVRD`s subsidiary, Vale Energia, plans to install a 250-MW thermal power plant to start operations in 2003, consuming 1.05 million cu m/day. Also, another CVRD project in the same city could use an additional 5 million cu m/day to produce hot briquetted iron.

Southern Cone integration

One of the most positive primary trends in the Latin American hydrocarbon industry today is the integration of natural gas and electricity in the Southern Cone.

Such integration refers to a series of isolated projects potentially linking giant reserves in Bolivia, Argentina, eastern Peru, and Brazil`s Upper Amazon-Solimoes, Campos, and Santos basins to prospective gas consumers in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.

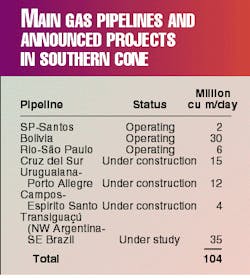

These projects are summarized in Table 2.

Bolivia-Brazil pipeline

The 3,000-km BTB pipeline from gas fields in the Santa Cruz area of Bolivia to Sao Paulo and PortoAlegre, was built for an estimated cost of $1.8 billion. The pipeline crosses the Bolivia-Brazil border through the states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Sao Paulo, then the southern states of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul.

The construction of the northern BTB segment, with 2,046 km of pipeline connecting Santa Cruz to Sao Paulo, took 13 months and $1.3 billion. The southern segment, with 1,170 km linking Campinas, Sao Paulo, to Porto Alegre, started construction last September and should be inaugurated this summer.

The pipeline started supplying about 4 million cu m/day as of March 1999 to Sao Paulo, increasing to 8 million cu m/day when the southern connection is completed. Supply is scheduled to increase to 16.2 million cu m/day by 2006. The pipeline capacity, however, is 30 million cu m/day, and it is very probable that the supply timetable will not only be met but also could be accelerated to reach total capacity by 2006 (Table 3).

Two separate companies have been formed to own the Brazilian and Bolivian portions of the pipeline. Petrobras (through its Gaspetro gas pipeline subsidiary) owns 51% of the Brazilian company TBG and 9% of the Bolivian side of the project, making it by far the largest owner. The second largest owner is the Enron Corp.-Royal Dutch/Shell-Transredes consortium, which owns 85% of the Bolivian side and 20% of the Brazilian side. The BTB consortium of BHP Petroleum Pty. Ltd., BG plc, and El Paso Energy Corp. is the owner of a 6% share on the Bolivian side and 29% on the Brazilian side.

Uruguaiana connection

One very possible channel will be through the Uruguaiana connection. This consists of two complementary projects: the connection between Argentina`s northwestern and Neuquén basin reserves and the Brazilian city of Uruguaiana, Rio Grande do Sul, and the Uruguaiana-Porto Alegre pipeline within Brazil.

The first segment is designed to carry 8-14 million cu m/day of natural gas into Brazil and has already obtained ANP`s authorization to import 12 million cu m/day, effective January 2001. The pipeline would connect the TGN system in northern Argentina to Uruguaiana on the Argentine border.

The Uruguaiana-Porto Alegre pipeline connection has been proposed by a joint venture of Gaspetro, with a 26% interest; YPF SA, Total Fina SA, TransCanada, Brazilian group Ipiranga, and Argentine companies Techint and Cia. General de Combustibles will share the remaining interests. YPF has guaranteed a 70% share of all volumes of gas will be supplied from its reserves in the Neuquén basin. The 24-in., 615-km pipeline will cost about $265 million and is scheduled to start operations on December 2000. ANP has already granted authorization for imports of 12 million cu m/day for this group.

Cruz del Sur

Another strong bet for the supply of Argentine gas to Porto Alegre is the Cruz del Sur pipeline project, led by BG and Pan American Energy (a consortium of BP Amoco plc and Bridas Sapic). It entails building a 24-in., 970-km pipeline linking Punta Lara, near Buenos Aires, with Porto Alegre, crossing 50 km below the Plata River through Colonia, Uruguay, and Jaguarao, Rio Grande do Sul. A complementary pipeline will also connect Colonia to Montevideo. Expected total volumes for the projects are estimated at 20 million cu m/day, of which 17 million (85%) would be dedicated to Brazilian markets and the remaining 3 million to Uruguay.4

The estimated investment for the Cruz del Sur pipeline is $420 million, of which $150 million is to be allocated to the Plata River crossing. Although the price for the gas is not yet defined, the pipeline tariff is set at $0.15/MMBTU. Pan American assures that its Argentine gas will reach Porto Alegre at much more competitive prices than Bolivian gas coming via Sao Paulo. Pan American has gas reserves in Argentina`s Austral, Noroeste, and Neuquén provinces totaling 350.6 billion cu m, of which 58 billion are proven.

Mega project

The Loma La Lata-Bahia Blanca pipeline also has Brazilian participation, as the so-called Mega project consists of a petrochemical feedstocks complex situated at Bahia Blanca, Buenos Aires province, to be operated by a partnership of YPF, Petrobras, and Dow Chemical Co.

It will use natural gas to produce ethane for Argentina and propane, butane, and natural gasoline for Brazilian markets.

Initial investment is expected to total $670 million. The Mega project will use 5 million cu m/day of natural gas to be supplied 50-50 by YPF and Perez Companc.

BTB-Cuiabá pipeline

Enron`s Bolivia-Cuiabá gas pipeline is another dedicated project in the region.

This 618-km pipeline will connect the BTB pipeline to the city of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso do Sul, to supply Enron`s 480-MW thermal power plant.

Enron also received ANP`s authorization to import 2.8 million cu m/day of gas into Brazil as of August 1999.

It is expected that, after slowing down during the last 2 years, the process of energy integration in the Southern Cone is gaining impetus again as the BTB pipeline starts full operations. As investors start to be able to fully grasp how the Brazilian markets actually develop, this will probably translate into another round of pipeline building during 1999-2003.

Northeast system

Brazil`s Northeast system is defined by the regional natural gas reserves located onshore in and off the states of Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Sergipe, Alagoas, and Bahia; the interregional connection provided by the Nordestao pipeline; and the consuming markets of the coastal capitals and other main cities.

Although this system has the characteristics of actual self-sufficiency, there has been speculation about future connections southwards, through a 600-km line between Salvador, Bahia; and Sao Mateus, Espirito Santo. However, this alternative is very unlikely to be viable within the next 5 years.

On the supply side, Bahia and Sergipe have reasonably stable production, while Rio Grande do Norte and Alagoas production has been steadily increasing. Total regional estimated reserves are currently 103.1 billion cu m, of which 63.3 billion are proven. Distribution among the states and basins is shown in Table 4.

On the demand side, existing contracts between Petrobras and the state distribution companies have already established volumes of 5 million cu m/day.5 This figure does not include the required volumes for the development of the numerous thermal power generation projects proposed for the region. The main projects are enivisioned for Macau, Rio Grande do Norte, a 330-MW plant to consume 1.4 million cu m/day; two plants at Suape, Pernambuco, each for generating 480 MW and consuming 2 million cu m/day-one led by Shell, probably relying on LNG imports from Nigeria, the other led by state electric utility Celpa, recently privatized; and at Pecém, Ceará, a 240-MW plant to be built by a joint venture of Petrobras, Gaspetro, Texaco Inc., and CSN Group, to consume 1 million cu m/day.

The backbone of the Northeast system is the Nordestao (Gasoduto do Nordeste) system, a 12-in., 424-km gas pipeline linking the Guamaré terminal in the producing state of Rio Grande do Norte to the city of Cabo near Recife, Pernambuco, with branches to Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Campina Grande, Pernambuco, and other main cities of the Northeast region. This gas pipeline is currently being expanded from both ends: from Guamaré, a new 10 and 12-in., 380-km line will carry natural gas up to Fortaleza, Ceará, and the neighboring new port of Pecém, with capacity of 3.2 million cu m/day. From Cabo, another new 12-in., 207-km line, with capacity of 2 million cu m/day will reach the city of Pilar, Alagoas, this summer. Thus, the whole Nordestao complex will, in the near future, connect the whole coastal region. It will encompass the area surrounding Fortaleza down to Salvador, Bahia, with a total length of more than 800 km, linking all the main cities and markets of the Northeast region.

The nine northeastern states, which account for close to one third of the country`s population, are still relatively poorer than the rest of the country but have been growing economically at a much faster rate. With hyperinflation brought to an end by the Real Plan in 1994, consumption has been on the rise. Industries such as shoes, textiles, and even automobiles have begun moving north to take advantage of this new market and of the area`s abundant natural resources, skilled labor, fiscal incentives, and low-cost industrial sites.

In 1997, GDP in the Northeast grew 5.6%, while in Brazil, overall growth was 3%. This performance was largely credited to the growth of industrial, construction, and service segments, which expanded in the region by 10.2%, 27.2%, and 4.5%, respectively, compared with increases of 5.5%, 1.3% and 3% in Brazil as a whole.

The Northeast region of Brazil presents strong indications of steady energy development in the coming years, especially in the industrial and power generation markets. Governments, planners, and investors within the region know of the advantages of constituting an independent, integrated natural gas system. As it stands today, Nordestao already uses 97% of its total capacity of 2.26 million cu m/day. When all connections are completed, Nordestao will be the region`s integration engine, giving enough flexibility for the consolidation of natural gas as a main energy source for the region. Distribution systems are expected to proliferate in Fortaleza, Natal, Recife, and Salvador.

In addition, selected industrial complexes will develop by using mainly natural gas-fired thermal power (Suape and Pecém). The start-up of production from the Pescada-Arabaiana areas this past spring immediately boosted supply of natural gas in the region by an additional 1.5 million cu m/day.6 New discoveries onshore and offshore are expected to happen as a result of new exploration in areas to be tendered by the ANP in the next three rounds.

Amazonian system

The northern region of Brazil is situated very far from the major consuming centers and presents well-known operating obstacles for both upstream and midstream activities. The Amazon jungle, vast distances, environmental sensitivity, and a complex political structure comprise a difficult scenario for any newcomer interested in participating in this isolated, almost autonomous system.

The Amazonian system is current formed by the gas reserves of Solimoes, to the west, and Mid-Amazonas, to the east, combined with consuming markets at Manaus and Porto Velho, with future possible connection to other smaller centers in the mid-to-long term. There are very tiny possibilities for this system to be soon connected to the systems of Argentina and southern Brazil.

Pipeline projects under study today consist of the following: a 16-in., 150-km line connecting Juruá and Urucu reserves, followed by spurs to both Manaus (18-20 in., 700 km) and Porto Velho (12 in., 500 km).

Apart from the evident difficulties to link such distant reserves and markets, another important setback is seen in the region: Local administrations do not seem to have visions similar to those of the federal authorities regarding the concepts of transportation and distribution of natural gas. Disputes on the relevant jurisdiction of each are still a regular component of local business analysis and a driver for political agreements that never prove to be realistic in terms of the established tariffs, prices, and volumes negotiated.

Another main concern is the confirmation of market growth expectations. Projections used by the federal and local governments to establish price and volume protocols in the past have to be taken with caution and realism. Although it is true that Porto Velho may have a more accelerated growth in energy demand than Manaus, the volumes of future natural gas consumption for these two main regional centers have always been seen as figures to proven.

Nevertheless, the good news for natural gas is the fact that hydropower plants in the region cannot any more rely on the government`s and the multilateral agencies` support, due to the higher initial investment required and the environmental and efficiency threats caused by the region`s geography. In addition, it is known that the cost of alternate fuels in the region is extremely high, leaving much room for natural gas to penetrate both power generation and industrial markets.

Recent announcements of new reserves in the Mid-Amazonas basin may reshape the region`s system of supply and demand for natural gas in the region. However, many definitions are yet to be established at regional and federal levels in order to make progress with the insertion of natural gas as an alternative source of energy.

Reforms, deregulation

Constitutional amendments were passed in 1995, after a lot of ideological and political disputes, allowing private investors to participate in exploration, production, refining, and transportation of hydrocarbons; electric power generation and distribution; and other related activities. In all sectors, similar reforms are expected to boost private participation and to generate more than $80 billion in investments to 2002.

For more than half a century, the state was the great driving force in all infrastructure sectors in Brazil. For the oil business, Petrobras was created in 1954 and was granted the exclusive right to plan, manage, and to carry out petroleum activities within the country.

On the negative side, the state monopoly resulted in a total ban on direct private investment participation; severe limitations to the development of the sector`s labor market, training and research activities and technology transfer; recurrent financial problems; irremediable direct subordination to governmental policies and rules; and the lack of concern towards creating a sound domestic contingent of private investors apart from the same satellite team of suppliers to the state monopoly. On the positive side-and there is a positive side concerning Brazil, valid at least up to the mid-1980s-the state managed to compensate for the critical lack of interest by private and foreign investors for carrying out petroleum activities in Brazil during the 1950s and 1960s, when other, better options, including the Middle East countries, were still an easier and more lucrative alternative. Also, the country managed to maintain a centralized control and planning of the development of its oil sector, enabling it to quickly redirect objectives or create alternatives, to avoid product shortages, or to absorb price impacts during periods of crisis.

It also succeeded in creating a petroleum operations company that fulfilled the national objectives, developed an international presence, and built a special reputation in technological niches such as deepwater activities, shale oil production, and rainforest development operations.

Of course, all this had certain costs that somehow were paid by Brazilian society, and one could always argue that it could be conducted otherwise. However, it is always important to keep in mind that, in the background of the Brazilian opening, probably unlike other countries, there is no such "failure sentiment." On the contrary, there is a proud feeling that, despite all difficulties, Brazil managed to build a solid and respectable petroleum industry and that this restructuring process just follows as a natural development to insert the country in the new world order`s context.

Background of reforms

The discussions regarding the new petroleum legislation were expected to generate intense debates on the best approach to restructure the sector, and these important factors had to be considered:

With all that as background, the government proposed and Congress approved a new petroleum law for Brazil, which, although not representing an exhaustive code regulating all aspects of our industry in detail, is yet an important first step toward reorganizing the sector in a modern, competitive, and productive manner.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the guidance of Dr. Delio de Oliveira Antunes, an icon in Brazil`s natural gas industry and the developer of many of the pioneering pipeline connections in the country, who assisted not only in this paper but throughout the last 6 years of the author`s dedicated studies on this matter; and to Mrs. Annette Hester, for the useful critiques of the final draft and for the last-hour revision of the text.

References

- Petrobras-"O Gas Natural no Brasil," Rio de Janeiro, September 1993.

- Expetro, 32 million cu m/day in 2006; Merrill Lynch, 37 million cu m/day in 2008.

- Estimates by Expetro. In 1997, the Ministry of Mines and Energy projected 9.8% for 2000 and 11.9% for 2010.

- Source: Mrs. Ieda Correia Gomez, chairman of Pan American Energy Brasil, January 1999.

- As of October 1998.

- Brasil Energia No. 211, June 1998.

The Author

Jean-Paul Terra Prates, a partner in and executive director of Expetro International Oil & Gas Projects Co. Ltd. and has the overall responsibility for the firm`s management and development. The founder of Expetro Group (1991), Prates holds an LLB (1984) from the Law School of the University of Rio de Janeiro, a Masters in economics and management (1992) from the Ecole Nationale Superieure du Petrole et des Moteurs (Institut Francais du etrole, Paris), and an MS (1993) in energy management and environmental policy from the University of Pennsylvania. His professional experience includes legal counsel for Banco Safra SA and Carbocom SA in contracts, corporate-fiscal planning, and debt recovery (1986-88). He received training and experience in international petroleum agreements working in the exploration contracts sector of the legal department of Petrobras Internacional SA (1988-91), and for the last 5 years has worked as a consultant for petroleum companies worldwide. Prates is also a founding partner of Prates & Carneiro Law Firm (Expetro`s affiliated offices for legal counseling), a contributing editor to the Oil & Gas Law and Taxation Review (Rocky Mountain Legal Foundation). He remains deeply involved in the developments of the opening of Brazilian petroleum sector, especially regarding its regulatory and institutional aspects.