ARCO's Villano project: Improvised solutions in Ecuador's rainforest

ARCO Oriente Inc. has just raised the bar in the evolving new paradigm of oil industry sustainable development in the rainforest.

The Ecuadorian unit of ARCO recently started up commercial operations in its Villano oil field development project in the Oriente jungle region of eastern Ecuador.

While at first glance a conventional oil field development, Villano in fact represents a new standard in the way oil and gas companies can work in an area with extremely sensitive environmental and indigenous cultural issues.

This is not unprecedented; oil and gas companies have in recent years pushed the envelope on how to effectively explore for, develop, and produce hydrocarbons in South America`s rainforest while preserving environmental and cultural values.

Among the other watersheds of this evolving paradigm are projects operated by Occidental Petroleum Corp. in Ecuador, Royal Dutch/Shell in Peru, and BP Amoco plc in Colombia (OGJ, Dec. 14, 1998, p. 24).

What makes Villano the new standard-bearer are two things: 1) the singularly novel way in which the project was literally improvised, essentially on the fly, to accommodate a roadless development in the rainforest; and 2) the way the project is serving as a prism for reflecting the increasingly complex web of environmental, social, economic, and political issues that has grown up around industry operations in the rainforest.

Background

ARCO, as operator with a 60% interest, and its partner Agip Petroleum (Ecuador) Ltd., 40%, in 1988 signed a service contract with the Ecuadorian government covering exploration and development on Block 10 in Pastaza province. In 1992, ARCO disclosed the Villano discovery, estimating reserves at 175-200 million bbl of oil. Under the 20-year production phase of the contract, ARCO and Agip are to recover 125 million bbl in compensation for exploration and development costs, plus a service fee.

The original plan called for production to start up in April 1999, with output expected to reach 30,000-40,000 b/d, depending upon capacity available in the Trans-Ecuadorian Pipeline (SOTE), the 330,000 b/d capacity trunk line that carries crude oil from oil fields in the Oriente to the refinery and export terminal as Esmeraldas. Capacity limitations on SOTE have long been a sore point for Oriente operators, which collectively can produce a great deal more oil-some say perhaps twice as much-as SOTE is currently capable of handling (see story, p. 25). The field started up production in late May and began shipments to SOTE last month.

Roadless mandate

The area around Villano, on Block 10, offers significant additional hydrocarbon potential (see map). As such, the project was conceived as a core for future development, said ARCO Oriente Pres. Herb Vickers, adding, "...As an opportunity for other prospects, it would make a lot more sense economically."

But, said Vickers, "We also wanted to present a model to government, to other companies, and to other South American countries that you can eat your cake and have it, too-that you can develop oil and gas safely in sensitive areas. We wanted to demonstrate to a larger audience a tool for showing that you can do development in a sensitive place and do things that haven`t been done before and go places that you haven`t gone before."

What made this initiative especially tricky is that Vickers`s mandate was to undertake development without building a new road in the area. Building roads in the Amazon rainforest has become a flashpoint for the oil industry, inviting growing criticism from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) around the world. The roads are considered by outside NGOs to be a pathway for rapid settlement in the rain forest, especially by nonindigenous groups, which in turn has a far greater impact on the environment and on the indigenous culture than the oil industry operations alone.

Complicating this situation is the irony that many of the indigenous groups want to see the roads built. In many instances, the natives see roads as an opportunity to expand output of their crops and timber harvests, often their sole source of income, as well as an opportunity to gain greater access to the outside world-precisely the sort of thing some NGOs want to prevent, ostensibly in the name of preserving cultural and environmental values.

But the NGOs are adept at using the internet and international media to bring great pressure to bear on governments, and Ecuador`s joined others in the region in committing to the ideal of minimizing new settlement in rainforest areas. The Oriente rainforests in particular rank among the world`s most biologically diverse regions.

Vickers`s mandate then became: Develop the Villano resource with minimal impact to the environment, and most important, without allowing new vehicle access in the rainforest. Just as important a part of that mandate was maintaining a good relationship with the indigenous communities by providing social and economic opportunities while minimizing or eliminating potential disruption.

Development model

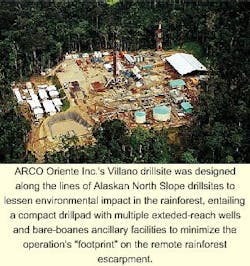

Because the field and proposed drillsite lay in a pristine area of rainforest, ARCO turned to a development model it has used successfully in another sensitive environment where it has pioneered low-impact development: Alaska`s North Slope.

ARCO has installed a "small-footprint" drillsite at Villano with a single drillpad and extended-reach wells. The total area of the Villano drillsite is only about 6.2 acres.

Production is remotely controlled from a central processing facility (CPF) about 40 km away-adjacent to an existing road in a previously "intervened" area-and electric power for the drillsite is generated at the CPF and supplied to the drillsite via cable.

Initial development calls for nine production wells and two injection wells for produced water. The only facilities at the drillsite are the wells, primary water separation equipment, pumps for oil transportation and water reinjection, a control room, emergency shelter, and a helipad.

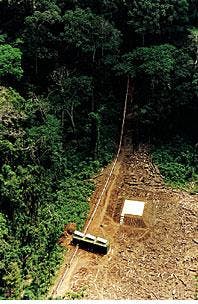

Even with the low-profile drillsite, ARCO still faced the challenge of bringing the crude to the CPF from the drillsite location atop a 500-ft high escarpment in primary rainforest via a 12-in. flowline that traverses a 4-km section of the Antisana Reserve, a sensitive habitat. >From the CPF, which also serves as the project`s operations center, the crude would have to be transported via a 16-in. secondary pipeline, the route for which would follow existing roads as much as possible. The secondary pipeline ties into SOTE near Baeza, 140 km north of the CPF.

Flow-line dilemma

ARCO`s main dilemma rested with the flowline: how to lay the line in a roadless area without heavy equipment and with minimal impact to the rainforest ecosystem-specifically without a typical 15-30 m wide right-of-way (ROW) and the usual heavy pipelaying equipment. Also, the flowline was not to be buried, in order to minimize excavation that would damage mature tree roots and cause erosion.

With that mandate in mind, Villano`s project managers largely had a free hand in how to go about designing the project.

Accordingly, the unusual structure of the project organization was, like much of the project`s engineering design approach, largely improvised.

Because of the environmental sensitivity of the Villano project area, ARCO Villano Project Director Ken Lathrop was apprehensive about turning the project over to the usual engineering, procurement, and construction conglomerate.

"We did some benchmarking and found that the EPC companies cost more," he said. So ARCO maintained management oversight of the project but hired Fluor Daniel Williams Bros., Tulsa, to serve as an engineering, procurement, and support services contractor. Fluor Daniel`s Robin Draper was named project engineer and given a charge to "think outside the box" in resolving the dilemma, while ARCO instituted an unconventional project management team structure and approach.

"Basically, we used (Fluor Daniel) as a body shop for ARCOellipse(and) used just three ARCO people to oversee the project. It wasn`t just ARCO people looking over a contractor`s shoulder; it was ARCO people really managing the project under an integrated team management approach."

Because ARCO`s contract calls for using local contractors where feasible, the company used local contractors almost exclusively. About 96% of the field labor was Ecuadorian.

For foreign contractors, Lathrop said, "We used leads from Fluor in the U.S., trying to get Spanish-speaking contractors. We took a look at their capabilities and figured out what they could provide for us; we didn`t leave much engineering in the contractors` hands. The organizational structure evolved as we came to understand the capabilities of the people available."

It was not always easy, Lathrop demurs, to convince ARCO and Fluor Daniel senior management of the wisdom of this approach.

Using local contractors-or the local offices of international contractors-not only helped ARCO in its dealings with the government, it often helped ARCO in terms of cost savings and in terms of logistics. "Local contractors know how to `live off the land,`ellipsealthough that puts a bigger burden on the operator."

ARCO undertook on its own many services, such as pipeline ROW acquisition, that usually go out to EPC companies. "We often outsourced certain functions to individuals outside the company but still maintained overall responsibility for those functions, said Lathrop. "We designed the structure of the PMT (project management team) around those people`s capabilities-there were not a lot of real strict lines there."

The flowline project was a big exception to the usual project management approach. "As owner, we retained control of the job. With an EPC company, you line out what you want to do then turn it over to the contractor. We couldn`t do that here because of the environmental sensitivity, so we retained control.

"We tried to figure out the best way to build the flowline, throwing out a lot of ideas in Fluor`s offices in Tulsa-but nothing worked out. We had meetings with local contractors in Ecuador, and they were pretty open and pretty willing to talk and to work with each other. We got a bunch of ideas, then tried to bid this as a design criteria and award it to whichever one best meets the environmental standards at the lowest cost."

Solutions

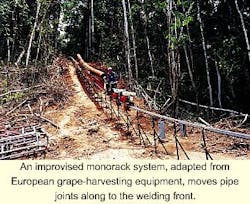

One Ecuadorian support-service contractor, Azul, came up with an idea for an overhead monorail crane system. Draper went over to Europe looking for a monorail but at first didn`t find one that suited the project`s needs.

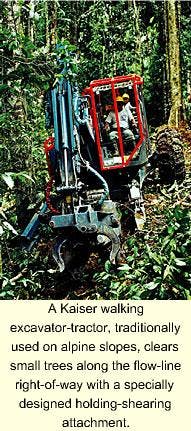

What Draper did find on that trip, however, was a piece of equipment that would be an all-purpose solution to solving some key flowline construction hurdles: a lightweight, helitransportable walking tractor-excavator, developed to work in areas where land is extremely expensive-such as Japan, Europe, and California-and capable of working on 45? angle slopes. The three Kaiser tractors used for the Villano flowline together cost $1.4 million.

Draper said the Kaiser tractors were initially designed for used in alpine excavation; he pressed the manufacturer, Kaiser Fahrzeugwek AG, of Liechtenstein, to develop modifications for the tractors-specially designed attachments for holding and shearing small trees, for grading slopes, and for pile-driving H-beam supports for the flowline.

The Kaiser tractors cleared, at a rate of 200 m/day, a ROW designed for a maximum width of 4 m, with the resulting average put at 3.5-3.8 m. The route`s design criteria entailed coping with slopes that were no more than a 45? angle. The steepest slopes encountered during construction were 38-40?.

The monorail prototype the project managers eventually settled on had been developed for transporting harvest loads in vineyards and orchards. It was a top-running, cogwheel-based monorack system from Habbeger AG, manufactured by Nikkari Ltd., for transporting wine grapes in hilly terrain. The monorack system was upgraded with a heavier chassis and increased horsepower and braking capability to accommodate a 1,000-kg joint of line pipe vs. the usual harvest-load capacity of 250 kg. As the pipe joints were transported along the monorack to be welded into place, the monorack was then dismantled behind the strung pipe and reconstructed ahead of the welding front. Draper noted that the jury-rigged monorack supports had to be reinforced every 3 m or so: "It fell apart at the very end, but it did what it was supposed to do." The monorack cost $1.3 million.

Cable trays containing power and fiber optic cables from the CPF to the drillsite were installed in a steel tray underneath the pipeline for protection against treefalls, and the cables were pulled manually through the tray, 500 m at a time.

Brazilian contractor Conduto won the contract for pipelaying, which also focused on indigenous labor and a minimal footprint by installing 13 small construction camps along the ROW. Each campsite consisted of eight five-building camps on a 4,000 sq m area, including the camp, material laydown area, and helipad. ARCO deployed a big Boeing 234 Chinook helicopter to transport the prefabricated camps.

Six of the campsites were left intact with helipad, to serve as permanent check-valve and shutdown sites. At each of these sites, a large steel shipping container was converted into a protective enclosure for the six shutoff-control valves, topped by solar power panels to power the programmable logic controllers for the pipeline valve actuator.

Pipebending was done at the campsites, and the pipe was strung one joint at a time, with each one transported via monorack to the welding front.

"We developed jib cranes to lay down the pipe, and the first few days, it took 45 min to get a joint down; we eventually got that down to 10 min," Lathrop said.

That effort boosted productivity to more than 20 joints/day from an initial 5-7 joints/day.

Flowline construction lasted 8 months, following a delay in getting started of 51/2 months-not because of technical hurdles or a lagging pace in construction work, but because of some trouble with indigenous groups that were demanding installation of a road, despite the fact that ARCO had a mandate to not put in a road.

With the flowline construction completed, ARCO began reforestation efforts with plants collected from the area and placed in nurseries near the camps. And it is reclaiming an area of the escarpment, where the flowline emerges from the forest, that has already seen intrusion by local companies extracting gravel and cutting timber. ARCO is developing a buffer zone in this area, in consultation with environmental and native groups.

CPF, drillsite

There is little that is extraordinary or complicated at the Villano CPF.

Power is supplied by three Wartsila crude-burning engines driving 5.3- MW generating sets, and an on-site topping plant produces diesel for local use.

ARCO has drilled two water injection wells at the wellpad, each rated to 17,000-18,000 b/d; free water-treater units are not in operation because the oil producing wells are not yet producing water, said Luis Paredes, ARCO Oriente production supervisor: "We figured on 3% water, but absolutely no water treating has occurred so farellipseThat`s probably 2-3 years away."

Plans call for drilling seven producers and one more injector this year and five more wells next year under the initial development program. The program calls for drilling the wells then pulling out the drilling rig and bringing in a workover rig to complete the wells.

The 21.5° gravity oil has a gas-to-oil ratio of 40-50:1, says Paredes: "So far, we`re not producing enough gas to light the safety flare."

ARCO is currently producing the V-2 and V-3 wells and soon will start up the V-4 well.

Although the contract with Petro-ecuador calls for an initial rate of 25,000 b/d, SOTE pipeline capacity is crimping output.

"We are currently producing 14,500 b/d, but we are going to have to shut in the best producer, V-2, because it is producing 8,500 b/d vs. the 5,600-5,800 b/d from V-3, and the allowable rate into SOTE now is only 5,600 b/d," Paredes said.

Injection into SOTE will rise to 40,000 b/d capacity after ARCO completes what it calls the "mini-SOTE expansion," which was initially set for September and now is set for January (see related story, p. 25). Delays were incurred in securing government approvals for the project.

Stakeholder relations

ARCO put relationships with indigenous groups in the Block 10 area at the top of its priority list in implementing the Villano project.

Since 1990, it has built two schoolhouses, teachers quarters, a community building, sanitation facilities, and medical facilities at the village of Moretecocha and similar projects in other settlements nearby.

ARCO is careful to point out the need to avoid limiting its assistance to what it deems "patrimonial" efforts: "ellipseWe will collaborate with our neighbors to draft a long-term plan for sustainable development and search for new ways to generate income and employment. We also hope to help them achieve a broader and better use of renewable resources, emphasizing conservation of the area`s biodiversity. And, finally, we will continue to improve community access to basic services such as education and health care."

One of the problems for ARCO`s neighbors on Block 10 is that the population there has increased dramatically since the company began providing health services-infant mortality is down, life expectancy is up. The growing population in itself is creating greater environmental pressure on the area.

There is the problem of widespread tree-cutting in the rain forest by the indigenous population. That`s a big part of the reason the locals were adamant about getting a road in the area. They cut the timber in a circular pattern around where they live; they want to use the road to get more timber to market, because they have more babies to feed; as a result, they run out of trees nearby to cut and then expand the circle broader.

This pattern is being repeated all across the Amazon.

Even with the dramatic success seen in stakeholder relations on Block 10, ARCO faces a fresh challenge with stakeholder relations on Block 24, to the south.

ARCO signed a production-sharing contract with Petroecuador for exploration on Block 24 last year (OGJ, May 11, 1998, p. 47). Initially, ARCO`s contract calls for it to conduct an environmental impact statement, invest about $6 million for seismic surveys on the block, and drill some exploratory wells.

But Block 24 has been targeted by NGOs seeking to halt further exploration in the region, and indigenous organizations are sharply at odds among themselves regarding support for or opposition to ARCO`s work plans. Lurid tabloid headlines tell of death threats and a "native war" against ARCO.

In fact, the company has secured agreements with most of the key indigenous groups but still faces opposition by some other organizations that claim to speak for all the natives in the region.

Vickers tells of the company`s difficulty in dealing with myriad communities and indigenous federations "with responsibilities that are all over the map."

He said, "We have been working closely with the Ministry of Environment and a development commission of locals, industry, and the military in meetings, discussions, etc. There is lots of pressure by outside people. A big concern is that the indigenous people want a road, but the environmental groups come unglued at that."

He added, "It`s a long, slow process just to come up with a way to shoot seismic. It`s just a process; you just have to work through it. We`ll be successful."

In fact, Vickers considers Block 10 to be more pristine; much more of Block 24 has been farmed and otherwise "intervened," he said. "But from the environmental groups` perspective, it`s a last holdout. We`re looking at setting up preserves and trying to reestablish the forest there; looking at establishing joint ventures with environmental groups and indigenous people. This is going to be a national problem and one that we will see all across South America."