China's natural gas industry awakening, poised for growth

China`s long-dormant natural gas sector is awakening in response to government initiatives on opening markets and improving air quality.

For many years, natural gas was a relatively unimportant part of China`s energy mix, considered by central planners as too valuable to burn and in short supply.

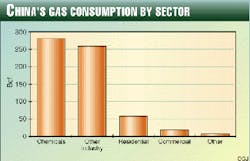

In a country with over 1.2 billion mouths to feed, natural gas was essentially earmarked for fertilizer production. In 1998, over 45% of Sichuan province`s 244 bcf of marketed production was used to produce fertilizer, with much of the remainder used in the petrochemical industry. Only a small fraction, 31 bcf, was used for residential heating and cooking, while no gas was used for power generation.

China`s natural gas industry has suffered from rationing and price ceilings that bear little resemblance to China`s true productive capability and costs. Consequently, gas consumption and production have remained stunted at little more than 500-600 bcf/year for the past 20 years. Meanwhile, China`s proved gas resources are estimated at almost 60 tcf, with recoverable reserves of over 37 tcf, sufficient to last 74-120 years at current consumption rates.

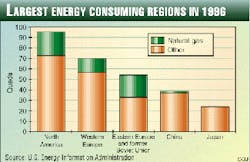

By comparison, North America possesses 10-11 years of gas reserves and produces 26 tcf/year; Western Europe, a major gas importer, has 17 years of reserves and produces 14 tcf/year; and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (FSU) together possess 83 years of reserves, producing 23 tcf/ year.

Signs of an awakening of China`s gas industry are now evident, with the ninth 5-year plan proclaiming that China will consume 6-7 tcf/year by 2010. Much of this is driven by the need for China to reduce its carbon emissions from coal consumption and its desire to follow a more market-oriented economic policy that allows energy choices to be made in the marketplace. However, for the industry to grow in an economically efficient manner, a number of regulatory reforms are needed to ensure that the industry becomes more sensitive to market realities rather than being run by government fiat.

Role of gas in China

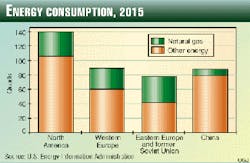

China consumed 37 quad- rillion BTU (quads) of energy in 1996, making it the fourth largest energy-consuming region on the planet. The world`s largest energy consumers are the U.S. (93 quads), Western Europe (68 quads), and the FSU and Eastern Europe (EE) (50 quads). Natural gas plays a significant role, providing 23 quads (24% of primary energy consumption) in the U.S., 13 quads (19%) in Western Europe, and 20 quads (40%) in the FSU-EE region. Yet in China natural gas provides less than 2% of primary energy consumption (Fig. 1).

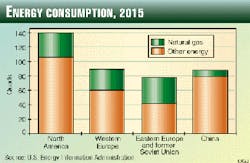

The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that, by 2015, energy consumption in the U.S. will grow to 111 quads, in Western Europe to 84 quads, in FSU-EE to 75 quads, and in China to 83 quads. Natural gas`s share of primary energy is forecast to grow in all countries, including China.

However, whereas natural gas consumption in the top three regions will reach 27-38 quads (27-47% of primary energy consumption), China`s gas consumption is forecast to reach only 3.6 quads, a little more than 4% of total primary energy consumption (Fig. 2).

Gas resources

It is not for want of natural gas resources that China consumes so little gas. Conservative estimates show that the FSU and EE together contain almost 2,000 quads of proved natural gas reserves, Western Europe 238 quads, North America 167 quads, and China 40 quads (Fig. 3).

The reserves estimate for China is undoubtedly very conservative. Compared with the other three regions, China is underexplored, and if coalbed methane and probable reserves are added, China could well have as much as 240 quads or more of natural gas.

China also has a number of options for expanding its natural gas supplies, from both domestic and nearby foreign sources. China`s Natural Resource Commission estimates that China has 57 quads of proved natural gas reserves, broken out as: Southwest China (mainly Sichuan Province), 19 quads; West China (Tarim and Tuha basins), 20 quads; South China Sea (mainly Nanhai basin), 8.5 quads; East China, 6.3 quads; and Northeast China, 4 quads.

Most of these reserves are essentially undeveloped, with reserves-to-production ratios ranging from 30 years in the Northeast to 65 years in Sichuan province and 243 years in West China.

Additional reserves are also available to China from surrounding countries. To China`s north, the Eastern Siberia basins of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Sakha contain perhaps as much as 50 to 60 quads of reserves within feasible transmission distance of China. To China`s west, Kazakhstan`s giant Karachaganak gas field and Turkmenistan`s Dauletabad field are also within potential transmission distance, with over 90 quads between them. Farther west and north of China, the Western Siberian gas fields contain over 2,000 quads of mainly untapped gas resources. Over the next 10 years, most imports of foreign gas are likely to come from Turkmenistan and Russia`s giant Kovyktinskoye field in the Irkutsk basin.

Gas production, use

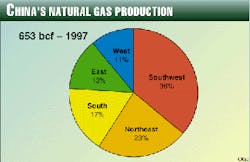

China currently produces approximately 653 bcf/year of natural gas from four established regions: Sichuan province, Shan-Gan-Ning (Ordos basin), Xinjiang Uy- gur autonomous region (Ta- rim, Chungeer, and Caid- amu basins), and Nanhai West in the South China Sea.

Sichuan province is the largest gas producing area, providing 303 bcf/year of natural gas. The South China Sea is the second largest gas producing region, providing about 113 bcf/year to Hong Kong and Hainan province (Fig. 4).

China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) forecasts domestic annual production of 1.0 tcf by 2000, 2.5-2.8 tcf by 2010, and 3.5-3.8 tcf by 2020. This forecast would appear reasonable, given China`s proved gas reserves of 46 tcf. Under this production forecast, cumulative production would amount to about 51 tcf over the next 20 years.

There is reason to be much more optimistic about China`s natural gas potential, given China`s underexplored status. The current estimate of reserves is quite conservative, and China could potentially double production from CNPC`s forecast, to perhaps 6-8 tcf/ year.

Adding to domestic production, China will probably import natural gas from Russia and the Caspian states, as well as some liquefied natural gas into its southern coastal region. There are plans to build a 4,600-km pipeline from Turkmenistan to West China that could also serve as the basis of a main artery for China`s domestic pipeline system. The pipeline would most likely have a capacity of 2 bcfd and carry about 600 bcf/year. Another pipeline on the drawing board, with a capacity of 2 bcfd, would bring natural gas from Russia`s Irkutsk basin south to Beijing.1

However, all this lies in the future. Presently, China`s gas transmission sector is in its infancy, providing supplies only to consumers that are near the producing fields. The exception is an 860-km pipeline that runs east from the Ordos basin to Beijing. However, even this pipeline runs well below capacity due to the lack of a viable gas market in Beijing.2 Before the gas industry can expand efficiently, China must restructure its national companies and liberalize the current pricing and gas allocation system.

Industry, market

The Chinese gas industry is vertically integrated and exhibits monopolistic and monopsonistic characteristics.

For example, Sichuan Petroleum Administration (SPA), a subsidiary of CNPC and the largest gas producer in China, explores for, produces, transports, and sells 244 bcf/year of natural gas. SPA`s natural gas is allocated to customers by central and provincial government mandate, with about 60% slated for fertilizer production. SPA`s remaining gas production is allocated to other industries-mainly petrochemicals-and the residential sector (13%). Therein lies the monopsonistic tendencies, with well over half the natural gas supply allocated to a single industry (Fig. 5).

China`s gas industry, as is the case with many other major industries in China, is not solely focused on producing and selling natural gas. It also has many "obligations" to provide schooling, health care, and other social services, more akin to a local government than a corporation. These services are paid for by cross-subsidies from profitable parts of the business and direct transfers from central and provincial government funds. These obligations will become increasingly onerous as industry is exposed to greater competitive forces.3

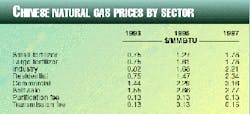

The government regulates the monopolistic and monopsonistic characteristics of the industry by establishing ceilings on wellhead prices, transmission tariffs, and consumer prices. However, as with the natural gas industry in the U.S. during the 1960s and 1970s, low price ceilings have acted as inhibitors of exploration and infrastructure upgrades, as well as strong incentives for the consumption of gas.4 This has had a deleterious effect on the industry, resulting in infrastructure decay and stagnant production. Recently, the provincial and national pricing bureaus have increased price ceilings in response to rising costs, but complete price and allocation liberalization awaits major economic reform.

Immediately evident from the table on historical prices by sector is the extraordinarily low price that fertilizer manufacturers pay for natural gas compared with other sectors. This pricing complied with China`s policy of promoting fertilizer production to feed a burgeoning population; however, it also means that fertilizer manufacturers account for 55% of the gas industry`s gross revenue from gas sales, while other industry provides 28%, and the residential sector provides only 15%. The gas transmission fee, fixed at 15?/MMBTU, is insufficient to cover the cost of upgrading and building additional pipeline capacity to secure new markets.

The table also shows a category of natural gas called "self-sale" gas, which currently has a ceiling price of $2.77/MMBTU. Self-sale gas was established in 1993 and is defined as any gas produced above the official quota. With the lifting of natural gas use restrictions, self-sale gas has the potential to become a major source of revenue for China`s gas companies. The price ceiling on self-sale gas presents a problem for the development of a free market in natural gas, but since it is the highest-priced gas, it also provides an incentive for producers to supply more gas and find new markets.

Despite low price ceilings, and even though China produces little gas compared with other fuels, the natural gas market is paradoxically in oversupply. This situation has resulted from a combination of government rationing that has kept consumption artificially low, the recent drying up of demand in some areas, and the failure of a market to develop as anticipated in other areas.

For example, the bankruptcy of a number of small fertilizer plants in Sichuan province has resulted in a market glut and falling prices. This glut is actually providing some motivation for SPA to find new markets to the East (Hubei province and Shanghai), where they could probably receive the self-sale price. However, much of the impetus for eastward expansion is as much a function of central government planning as it is the working of any market forces.

Infrastructure development

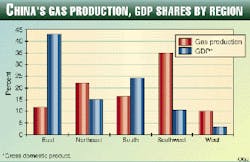

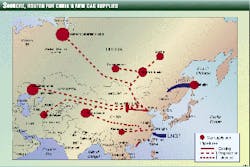

Most of China`s current natural gas production is located in the Southwest (Sichuan province) and the West. Meanwhile, the areas that are experiencing-and are expected to continue to enjoy-the most economic growth are in the East and Southeast (Fig. 6). A top priority for China`s planners is to construct long-haul natural gas pipe- lines to serve the energy needs of these growing areas (see map, below).

Currently, China`s pipeline system is regionally segmented, only connecting producing fields to nearby consumers. The first pipeline was built in Sichuan province in 1958, followed by two trunk lines (a southern section in 1966 and a northern section in 1988) that form a Sichuan annular trunk line, with a total length of 5,000 km. This is China`s longest pipeline. The second longest pipeline is the 860-km pipeline that ships gas from the Ordos basin to Beijing.

The development of China`s gas industry-both producing and consuming sectors-is predicated on building of an interprovincial and an international pipeline system capable of shipping gas from the western producing regions to the eastern consuming regions. China`s small regional system also needs to be upgraded. China has an ambitious three-stage program to build such a system, announced in its ninth 5-year plan:

Long-haul pipelines

CNPC plans to build a domestic pipeline system in three stages that would connect China`s major producing provinces to major inland and East Coast commercial and industrial centers.

Under Stage I, CNPC would construct a pipeline to ship natural gas east, from the Sichuan basin to Wuhan in Hubei province and then on to Shanghai. A pipeline would also be constructed to ship gas from North China (the Ordos basin), south to Xian, from where it would travel southeast to Xinyang in Henan province. A spur would also be constructed that links Xinyang to the main Sichuan-Shanghai east-west trunkline. Natural gas from Sichuan and the Ordos basin would provide Shanghai with 141 bcf/year by 2002.

A pipeline segment would also be constructed in western China to ship gas from the Qinghai basin to Lanzhou in Guangsu province.

Stage II would entail the construction of a pipeline from Lanzhou to Xian, which means that producing fields in western China can join northern producing fields and the natural gas fields of Sichuan to provide gas to areas in the middle and lower Yangtze River Valley.

Stage III would see the completion of a pipeline to link fields in the Tarim basin in far western China to the Stage I pipeline in Qinghai province. By 2010, the entire system should be capable of shipping 670 bcf/year of natural gas to eastern China.

For the moment, China plans two international pipelines, one to ship gas 4,600 km from Turkmenistan and a 1,300-km pipeline from Russia. Both pipelines would serve the eastern coastal region.

The pipelines would have the capacity to ship 700 bcf/year each to Jiangsu province and Shandong province on the East Coast.

Developing market demand

A major obstacle to the development of a gas system in China is the development of market demand. Recognizing this, the Chinese government is lifting restrictions that have limited natural gas use mainly to fertilizer production.

In terms of developing residential, commercial, and industrial demand, China would not be starting from scratch. Many cities already have local distribution systems that distribute manufactured town gas. This is similar to the U.K. in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which also had extensive town gas systems. The discovery and development of natural gas in the North Sea meant that all of these systems were gradually converted to accept natural gas.

The power industry is the sector that will likely see the most rapid growth in gas use. China`s ninth 5-year plan calls for China to double its electricity generating capacity in the next 10 years from 290 GW in 2000 to 550 GW by 2010. The plan estimates that 25%, or 65 GW, of incremental capacity will be gas-fired generation. If this is the case, then gas consumption by the power sector could well leap to as much as 3 tcf/year.5

Development barriers

There are many impediments to developing natural gas in China; some of them are applicable to industrial development in general, while others are more specific to the natural gas industry. We assume in this discussion that China will continue on the road of economic liberalization and privatization and that the state will gradually wind down its involvement in the day-to-day running of industry.

In general, the problems center on: the legal-regulatory framework and property rights, restructuring of state- owned enterprises, development of competitive markets, and development of regulatory bodies with clear responsibilities.

China`s government would appear to have recognized and be actively working to resolve many of these issues, although the pace of change is erratic as it struggles to balance the necessary changes with social obligations during the transition from command-and-control to a free-market economy. Impediments specific to the development of the natural gas industry are considered next, broken down into upstream, midstream, and downstream.

Upstream

Midstream

Downstream

Many of the recommended cures for these issues could take many years to implement. One immediate step that could offer relief to China`s natural gas industry would be to lift price ceilings on self-sale gas.

Although much of today`s natural gas market is under price controls and allocation quotas, new consumers need not receive any of these "benefits." To provide an immediate incentive for China`s producers, all new customers could fall under the category of self-sale.

Also, the price ceiling on self-sale gas should be eliminated to provide an incentive for producers to develop gas fields and find new markets.

As the industry develops, price ceilings on other categories of gas should also be lifted.

Conclusions

We have shown that China has access to domestic and foreign resources within transmission distance to develop a strong and vibrant natural gas industry.

The major obstacles are not the physical limitation of natural gas resources but the remnants of the old centrally planned economy that continue to hinder the industry`s growth.

China has already demonstrated a commitment to develop its economy along market lines in other sectors, such as the recently liberalized power industry.

The extension and continuation of this trend to the natural gas industry could spark substantial and rapid growth during the next 5-10 years.

References

- An alliance of British Petroleum Co. plc (BP) and Statoil first looked at exporting gas to China from the Kovyktinskoye field. Russia Petroleum and the Chinese government are studying plans for a pipeline. BP successor BP Amoco plc is still involved in the field`s development.

- Barely 3% of Beijing`s 12.5 million residents currently consume natural gas. There are plans to extend Beijing`s local distribution system into more residential areas; however, the power sector is probably the largest potential customer.

- The central government has already unleashed competitive forces among some state monopolies. For example, CNPC competes with Sinopec in retail gasoline markets; China Star competes with Sichuan Petroleum Administration in the upstream business, unencumbered by "social obligations."

- However, the consumption of natural gas was deliberately rationed.

- Calculated based on a capacity rate of 85% and 8,000 BTU/kw-hr.

- Some have proposed raising capital for the completion of the project on the international markets by issuing bonds or shares. It is doubtful whether the financial community would find shares very attractive, given the uncertainties associated with the project.

The Authors

Chris Ellsworth is the manager of the natural gas practice at Energy Security Analysis Inc. (ESAI) in Washington, D.C. With more than 20 years of industry experience as an economist and exploration geologist, he works with domestic and international clients on strategies for dealing with globally deregulating energy markets. He is editor of ESAI`s North American Natural Gas StockWatch and co-authored a book, Natural Gas Hedging, published in May 1999. Most recently, he contributed a section on China`s natural gas industry to a forthcoming ESAI report on the outlook for China`s oil and gas demand. Ellsworth holds a BS in geology from King`s College, London, and an MA in economics from the University of Houston.

Wang Zhong (Rosey) is a foreign affairs officer, senior interpreter, and procurement officer with the Sichuan Petroleum Administration (SPA) of China National Petroleum Corp. She has 10 years experience working on SPA-World Bank projects and with international oil and gas companies to restructure and develop China`s natural gas industry. Her current focus is a joint SPA-Gaz de France study of gas marketing opportunities in Sichuan, Chongqing, and Hubei. She holds a BA in American & British literature from Nanjing University and an MA in economics from Sichuan University.