Unocal goes to extremes to remediate two California petroleum spills

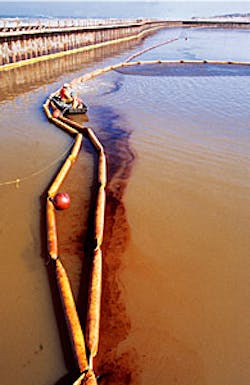

Unocal Corp. is using a number of remediation methods to clean up the Guadalupe diluent spill in California's San Luis Obispo County. Shown here is a skimming operation in a contaminated area that has been isolated with sheetpiles and excavated. The excavated soil is treated to remove contaminants, but residual contamination often remains at the original site, necessitating additional cleanup measures such as the skimming shown here. Photo courtesy of Unocal Corp.

- History of the Guadalupe-Avila Beach spills [387,703 bytes]

- Guadalupe diluent spill extent [242,214 bytes]

- Unocal Corp.'s project manager for the Guadalupe diluent cleanup, Gonzalo Garcia, inspects a beachfront area that contains sensitive plants and wildlife. [12,932 bytes]

- Photo shows the installation of a high-density polyethylene wall to isolate a contaminated area. [35,363 bytes]

- Although most of the leaked diluent is underground, this photo shows where some of it has percolated to the surface due to a high water table.[23,692 bytes]

- Unocal's on-site "living laboratory," shown in the photo, is designed to find ways to enhance bioremediation at Guadalupe Dunes. The oil company and California Polytechnic Institute are conducting the research, which they hope will ultimately lead to the development of "superbug" microorganisms for improved bioremediation. [18,381 bytes]

Estimates of the volume lost at Guadalupe oil field vary between 202,000 bbl and 476,000 bbl, making the spill comparable to the Exxon Valdez, Burmah Agate, Corinthos, and Argo Merchant tanker spills. It is at least twice as large as the infamous blowout at Union Oil Co. of California's Platform A in the Santa Barbara Channel in 1969, which released 100,000 bbl and is often touted as a key event leading to the environmental movement. (Union Oil Co. of California was the precursor of Unocal Corp.)

Despite their size, Unocal's Guadalupe diluent leaks never garnered the national publicity and attention of any of the events mentioned, because it happened slowly over decades, is mostly underground on leased private land, and apparently posed no widespread, immediate threat to human health or the natural world. But the ante was increased when bad weather, erosion, and migration sent the diluent into the ocean in 1988, and contamination was measured in groundwater, although not in sources used for drinking.

A second site in nearby Avila Beach, Calif., later became a problem for Unocal, despite its smaller size. In contrast to Guadalupe's diluent, the Avila spill consists of crude oil, gasoline, and diesel fuel that leaked under the downtown area and the beach over many years. Getting it out meant intruding upon the routine lives and infrastructure of a small town; razing commercial buildings such as stores, a local bar and yacht club, apartments, and houses and rebuilding it all.

Unocal has gone to extreme measures to clean up the Guadalupe and Avila Beach spills, using a variety of techniques to remediate these environmentally sensitive areas. But, just as the spills occurred over a long period of time, cleanup is proving to be a long-term project.

Cleanup

A few months ago-and after years of litigation, hearings, debates, emergency excavations, and recovery-Unocal began an 18-month excavation in the town of Avila Beach and is tackling a more widespread contamination at the 2,700-acre Guadalupe Dunes area.The Guadalupe problem is massive in scope, and cleanup is expected to be very expensive. It is estimated that extracting or breaking down most of the contaminant will take at least a decade.

Although the cleanups pose difficult technical and regulatory challenges, they may lead to new or more efficient remediation methods. In fact, Unocal could end up with a proprietary bacterial soup garnered from an on-site "living laboratory" that has already increased the efficiency of bioremediation by about 20% (see photo at right on p. 36). The not-so-secret ingredient is corn steep, added to traditional mixtures.

Even if the cost of cleanup is excluded, this has been one of the most expensive ordeals ever encountered by an oil company for release of a petroleum substance. Damages, penalties, and government agency reimbursements have piled up. These include: a state record penalty of $43.8 million for the Guadalupe Dunes contamination, under a settlement reached in 1998; $18 million for Avila Beach the same year (OGJ, July 27, 1998, Newsletter); and another $1.5 million in 1994, to settle criminal charges (OGJ, Mar. 21, 1994, Newsletter).

"Forty-four million (dollars) is just the front door," said one state official, who noted that the 1998 settlement does not preclude future litigation.

In 1994, Unocal pledged an open-ended budget to clean up the spill (OGJ, Mar. 14, 1994, p. 36).

No one at Unocal is comfortable in releasing cost figures-partly because work is driven by regulatory agencies. But it's known that Unocal has so far spent about $70 million on studies and emergency cleanup at Guadalupe oil field alone.

Unocal official Barry Lane says nobody knows the ultimate cost of cleanup, but that insurance will help defray costs.

Unocal has also given a $1.3 million grant to California Polytechnic Institute (Cal Poly) to establish the living laboratory site at which to study enhanced bioremediation techniques. And the company donated $200,000 to the city of Guadalupe, Calif., and spent millions more settling property claims at Avila, which are confidential.

Unocal intends to buy the entire 2,700-acre Guadalupe Dunes property from a trust that includes foreign owners who have held up the purchase because of lawsuits among themselves. If Unocal finally buys, it won't be selling it for profit but, instead, marking it with "conservation easements" so that it can never be developed. If a purchase proves impossible, Unocal will exchange some other property for the same purpose.

These problems also present a litigation nightmare for Unocal, as the company has confronted various suits brought by state, regional, and local agencies and public groups such as the Surfrider Foundation and the Sierra Club. Some were settled by agreeing to damages and penalties, but others continue to this day.

The company originally kept the leaks under wraps and denied it was responsible, according to court records. But after the diluent was noticed on a beach in 1988-Guadalupe field's peak production year-Unocal started a process of discovery that continues, and even widens to other areas, still today.

The two spills

Although pipeline leaks are the common thread in both locations, the two spills couldn't be more different.At the beachside town of Avila Beach, Unocal faces angry residents because their beloved downtown is being razed and rebuilt, displacing businesses and homes until at least 2000. In addition, some residents are claiming that various health problems are tied to the pollution.

Guadalupe Dunes, on the other hand, is a wild area on private property. It is off-limits to the public but part of an expansive National Natural Landmark system that includes rare and endangered plants and animals.

Deer roam freely there, and workers have also seen bears and bobcats, along with scores of smaller creatures that are accustomed to the small band of workers at the site.

Guadalupe Dunes

Unocal and its Union Oil predecessor have operated in the Guadalupe Dunes since 1951, when the company acquired the field from Continental Oil Co., which had drilled the first commercial well there in 1948 but shut it down the next year. The company used a kerosine-like diluent from a nearby refinery at Santa Maria, Calif., to thin the thick crude oil (8-10° gravity) produced in the area and transport it through 170 miles of pipeline.Located 15 miles south of the city of San Luis Obispo, the 2,700-acre Guadalupe Dunes area lies within the Nipomo Dunes system and is bounded by the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Maria River, dipping slightly into Santa Barbara County (see map, p. 35).

The diluent has leaked almost everywhere in the area. There are about 90 known plumes, and some are visible at the surface (see photo at left, above).

"(The Guadalupe remediation project) is an incredible task and probably the most highly scrutinized (environmental cleanup) site in the world," said Gonzalo Garcia, Unocal's project manager for the Guadalupe site.

A survey of the dunes area found 14 habitats that include some rare and endangered animals and 250 plant communities.

Garcia is not an engineer but a self-described "environmental guy" who started out as a roustabout, then studied environmental sciences, and who views his job as a steward for the land, plants, and animals.

That's important, to make amends for what Garcia calls "public outrage" over the leakage. But he is equally adamant that "our whole team is committed," from the officers in the corporate boardroom to the field workers.

Proof of that came in 1994, when Unocal pleaded "no contest" to three criminal charges that it leaked thousands of barrels of diluent and failed to report it. Unocal Vice-Pres. John Imle Jr. came to the area and faced the public, saying, "I personally...owe this community an apology for what's happened. I further want to state (that) we fully accept responsibility for that diluent being there."

Imle also vowed that Unocal would spend "whatever it takes" to clean up the spill.

That doesn't mean there hasn't been disputes over how to do it, however. Unocal would rather use more in situ bioremediation than excavation, on the grounds that it is less destructive. But bioremediation takes more time than the agencies and public have patience.

"I call it the DNA approach-or Do Nothing Approach-which doesn't call for any intervention," said Dr. Raul Cuno of Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, referring to in situ bioremediation.

Cuno, a recognized expert worldwide in microbiology, is working closely under a Unocal grant at the dunes' living laboratory, trying to find a "superbug." If they can pull it off, public agencies just might allow more bioremediation.

"To dig up a site destroys the site," Garcia maintains. "There is no magic cure today."

So agencies, after scrutinizing, criticizing, and modifying Unocal's cleanup plan, have finally agreed on a variety of methods to be used. Not all of them are to Unocal's liking.

They include:

- Drilling vertical extraction wells.

- Installing vacuum drop tubes, which draw vapor and liquids up and oxygen down to enhance biodegradation.

- Excavating about 790,000 cu yd of of soil (426,000 cu yd of contaminated soil and 364,000 cu yd of overlying clean soil) from 17 sites.

- Embedding steel sheetpile walls to 40-ft depths to prevent slides and minimize surface area disturbance during excavations, notably on the beach and near the Santa Maria River.

- Biosparging (introducing air into the subsurface to promote growth of aerobic microorganisms).

- Applying pump-and-treat technology (groundwater extraction and cleanup).

- Using hot-water flooding to loosen any thick crude oil (to be used on a trial basis at some sites).

- Allowing natural attenuation (letting nature take its course, but only at sites with less than 1,000 ppm of diluent).

Unocal has already excavated 220,000 tons of sand at the beach area in 1994 as the result of an emergency abatement order. It used thermal de sorption, or baking the oil off contaminated sand at 700? F. in large, revolving kilns. The desorption units used were the largest in the U.S. at that time.

Problems continued to crop up, however, when the Santa Maria River changed course during inclement weather, prompting more emergency actions. From that experience, Unocal knows the cleanup may continue to bring surprises and anomalies.

In any case, Garcia said he doesn't expect full cleanup "in my lifetime."

Avila Beach

The Avila Beach contamination is primarily from underground pipelines carrying crude oil, gasoline, and diesel fuel to the Unocal pier from an adjacent tank farm and fuel to the storage area from tankers. In operation since 1910, the terminal is only about 15 miles from the Guadalupe Dunes spill at the northern end of San Luis Bay.Five of ten pipelines were active until 1996, when terminal operations ceased and Unocal filed a cleanup and abandonment plan. Two years prior to that, Unocal started a major beach excavation, removing and cleaning 7,500 cu yd of sand over a 2-year period.

Earlier this year, Unocal officials handed out earplugs to visitors and residents as they pounded in a 2,700-ft sheetpile wall at the beach prior to excavating even more contaminated soil.

The difference between this spill and the Guadalupe leak is that Unocal must raze 23 buildings downtown, some of which are homes and apartments, in order to excavate below them.

The total spill volume is estimated at nearly 10,000 bbl and will take about 18 months to clean up. The project began in November and affects 9 acres of the 58-acre town. Altogether, 400 residents will be displaced.

Overall, Unocal will excavate an estimated 100,000 cu yd of soil, or nearly 7,000 truckloads.

As might be expected, the townspeople are angry at the contamination, noise, and construction traffic, and at being displaced-so much so that Unocal's Project Avila manager, Denny Lamb, retired in September, after a 35-year career, with the comment: "This has been one of the ugliest experiences I've ever had."

Lamb was replaced by Bill Sharrer, who has worked as a Unocal environmental supervisor and holds a degree in hydrology.

"I can't think of any other situation like this," Sharrer said, referring to contamination of downtown and beach areas. Unocal had to acquire at least 30 permits from 10 governmental agencies to do the work.

To improve public relations, Unocal has set up a web site (http://www.projectavila.com) that not only gives updates on the project but helps residents apply for compensation.

Unocal is using a number of techniques besides excavation at Avila Beach. These include biosparging, addition of soil nutrients to speed bacterial breakdown, vapor recovery, and soil venting.

Gonzalo Garcia Guadalupe project manager for Unocal Corp says,

"The Guadalupe remediation project is an incredible task and probably the most highly scrutinized environmental cleanup site in the world."

Copyright 1999 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.