Supply-demand disparity tops 1998 oil trends

Global oil markets were characterized by oversupply and falling prices in 1998. This trend marked a turnaround from recent years, when supply and demand were relatively balanced.

Demand growth began to slow in late 1997, as the effects of the Asian economic crisis began to take hold. But markets did a turnaround in 1998, and demand growth for the year was at its lowest level since 1985.

These are the conclusions of the latest annual analysis of world oil trends by Arthur Andersen and Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA). The firms revealed the results of their joint analysis in Houston last month (OGJ, Feb. 15, 1999, Newsletter).

"Over the last several years, there has been a degree of balance in world oil supply and demand," said Arthur Andersen and CERA. "Supply increased as technology lowered the cost of oil exploration and production and extended the reach of oil production into previously inaccessible areas. At the same time, a changing international political scene led more countries to open their doors, often at attractive terms, to international oil companies. Demand also increased, pushed higher by what at one time seemed to be an unquenchable thirst for oil in Asia, and by strong growth in Latin America and North America.

"Asellipsethe 1998 World Oil Trends (report) warned, however, the element of surprise is an omnipresent feature of the oil business," said the firms. "The balance that began to unravel in 1997ellipsecame completely undone in 1998 and marked a turning point in the convergence between rising oil supply and demand.

"The combination of improving technology and liberalizing investment regimes continued to boost oil supplies, but faltering economies in Asia led to a severe slowdown in world oil demand growth. The result was a 33% decline in the average annual price of crude oil (in 1998 vs. 1997)."

Supply-demand imbalance

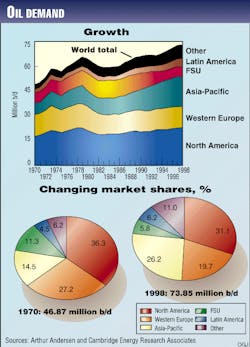

Global oil demand grew by only 230,000 b/d in 1998, a mere 0.3%. In Asia, where demand had been expected to increase by 1 million b/d last year, it instead declined by almost 500,000 b/d (see chart, p. 36).Regional demand changes were: Latin America +3.6%, Middle East-Africa +2.1%, Europe +1.3%, North America +1.0%, former Soviet Union -1.7%, and Asia-Pacific -2.1%.

Regional shares of world oil consumption changed little in 1998 vs. the previous year. The demand shares of the FSU and Asia-Pacific regions declined slightly, while those of North America and Europe increased.

World oil consumption rose by 680,000 b/d in 1998, an increase that surpassed demand growth by almost 200% Table 1 [136,247 bytes]. Regional changes were: Middle East +4.1%, FSU +0.9%, Latin America +0.6%, North America +0.4%, and Asia-Pacific -0.3%, with European output remaining unchanged.

The supply-demand imbalance created a "substantial build of oil inventories" throughout 1998, said Arthur Andersen and CERA: "The build was also encouraged by contango in oil futures marketsellipseThe higher value of oil in the future compared with the present encourages companies to buy oil and put it into storage."

Crude oil stocks in the U.S. rose to their highest level since 1993 and remained high for most of the year. And stocks in Europe last year were 7% higher than in previous years.

"Rising inventories in the United States and Europe, however, provided only one clue as to where excess crude oil was being stored. The question of the 'missing barrels' became a feature of the oil market for much of the year," said the firms.

"Missing barrels" is the term used to describe an unaccounted-for discrepancy between the supply and demand figures reported by the International Energy Agency (OGJ, Nov. 23, 1998, p. 36).

High inventories keep downward pressure on oil prices throughout the year. The average annual crude price fell 33% from 1997 to 1998. The West Texas intermediate average spot price fell from $15.92/bbl in the first quarter to $12.78 for the fourth quarter. Quarterly average Brent spot prices fell from $14.01 in the first quarter to $11.08 in the fourth.

Arabian light averaged $12.62/bbl on the spot market in the first quarter and $11.39 in the fourth. And the U.S. average wellhead price of crude fell from $12.39/bbl in the first quarter to $9.21 in the fourth.

OPEC vs. non-OPEC oil

Oil production from Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries members rose 380,000 b/d to 27.46 million b/d in 1998. But this belies the fact that output in 7 of the 11 member states was down for the year. Iraq's production, which grew 960,000 b/d for the year, was clearly responsible for the increase in OPEC output.Arthur Andersen and CERA called 1998 "a very difficult, if not disastrous, year for OPEC member countries." The key development, in addition to the increase in Iraq's production, was the signing in April of watershed production-cut agreements by OPEC and a few non-OPEC countries.

"The OPEC cut agreement has defied all expectations," said CERA Pres. Jo- seph A. Stanislaw. "It has lasted almost a year."

But its effects are far-reaching. According to the joint report, "To a certain degree, the OPEC agreements of 1998 sounded the closing bell on the era of production quotas that OPEC first established in 1973.

"The production levels from which OPEC member countries agreed to cut back in 1998 were those at which production was actually taking place, not the levels in the quota. In so doing, OPEC acknowledged and accepted the reality that it was no longer the production quotas but production itself that mattered. This was something of a victory for countries such as Venezuela, Qatar, and Algeria, which were reaping the rewards of plans put into place to encourage the participation of the international oil companies in their oil industries."

Non-OPEC output in 1998 averaged 38.23 million b/d last year, an increase of just 300,000 b/d from 1997. Arthur Andersen and CERA say this is the weakest increase in non-OPEC production since 1993.

"It was not one particular factor that caused non-OPEC production to increase so little," said the firms, "but rather a series of unrelated events in different parts of the world, including: low oil prices, technological difficulties, accidents, guerilla action, and reduced investment. In addition, several non-OPEC countries joined with OPEC in making voluntary production cuts to lend support to (oil) prices."

Refining

Refineries benefited little from the low oil prices, because capacities grew while demand weakened. Distillation capacity at the end of the year was 420,000 b/d higher than at the start, as a result of capacity increases in many regions. Even in Asia-Pacific countries, refining capacity grew 460,000 b/d during 1998, despite declining demand.Refiners around the world also increased their conversion capability, enabling them to produce more light transportation fuels from heavier feedstocks. Thermal operations increased by 5.2%, or 400,000 b/d, worldwide, and catalytic cracking grew by 2.9% (also 400,000 b/d). Most of the increased cat cracking capacity was in the Asia-Pacific region, according to the report.

Implications

Oil's dismal year has had a number of consequences for oil companies and the workers they employ.Victor A. Burk, Arthur Andersen's managing director for energy industry services, listed the obvious results of depressed demand and prices. Among them are layoffs, reduced investments, and "an unprecedented level of mergers and acquisitions," said Burk.

Another issue of concern to him is that the petroleum industry is no longer viewed as an attractive place to work. This will make it increasingly difficult to replace lost talent with new workers when business fundamentals improve.

Despite all these negative indicators, however, Burk sees what he hesitantly calls "an underlying sense of optimism" in the industry. Companies are fighting hard to stay afloat by refocusing their strategies, he says.

Stanislaw believes the changes taking place in the industry are more than just a response to low oil prices. "This is a structural change in the industry," he said. But the important issue is not how companies react to the present crisis but rather how they respond when prices rebound and conditions improve: "The successful companies of tomorrow will incorporate the lessons of the low oil price environment into their corporate strategies and remember them even when prices recover."

Copyright 1999 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.