Deepwater exploration seeks value over volume in new oil price environment

Tayvis Dunnahoe

Exploration Editor

Before the mid-2014 oil price decline, offshore exploration meant chasing barrels and finding giant fields, but many of them could not be developed due to spiraling costs. After 3 years of constrained budgets and shelving planned deepwater developments, the industry is leaner and more efficient. Today's deepwater exploration is focused more on finding value than volumes. "It's the difference between night and day," said Julie Wilson, research director of global exploration, Wood Mackenzie. "Exploration companies are taking a lean approach."

Cost-curve comparison

For the last few years, some operators have set aside deepwater plans to focus on tight oil plays in the US Lower 48. West Texas's Permian and Oklahoma's Sooner Trend Anadarko basin Canadian and Kingfisher counties (STACK) and South Central Oklahoma's Oil Province (SCOOP) in central Oklahoma are marked by rapid innovation that has quickly expanded production. Companies have reduced learning curves in these plays by applying factory drilling approaches incrementally.

Marathon Oil Corp. and ConocoPhillips both stepped away from deepwater to develop their tight oil positions since 2014. "Companies looking for short cycle times and flexible spending will invest in tight oil where they have good positions in these plays," Wilson said. "The offshore market has fundamentally changed with tight oil."

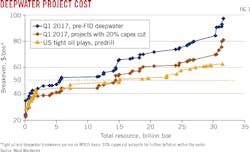

Wilson points out that inflation, especially in the service sector, is returning to tight oil while deepwater costs continue to fall. As the cost curves for tight oil and deepwater come closer together, deepwater projects will become more competitive on a breakeven basis (Fig. 1). But the key difference in capital flexibility remains.

Trendspotting

Operators are making deepwater projects more competitive by advancing a number of fronts. Operators have redesigned projects to be more capital efficient. Some large projects are being phased to reduce upfront outlays and provide flexibility in spend, while smaller fields can use nearby infrastructure to be developed via subsea tie-back. Simple subsea tie-backs that are incremental to an existing field are highly competitive with tight oil. Overall cost reductions in deepwater are achieved through deflation and, more importantly, efficiency improvements involving lessons learned in tight oil plays.

Projects redesigned

Overdesign, a major source of redundancy, has been stripped away from deepwater operations compared with pre-2014. Operators in the US Gulf of Mexico have been at the forefront of cost reductions driven by project optimization: drilling fewer wells and targeting sweet spots. Companies have also changed their facility choices to be more fit-for-purpose.

BP PLC shifted from a spar to semisubmersible in its Mad Dog Phase 2 development in Green Canyon Block 825 in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico (OGJ Online, Mar. 21, 2017). The new oil platform will produce 140,000 bo/d from 14 wells beginning in 2021. BP made its decision in December 2016, when the oil price was about $50/bbl, having previously postponed this project in 2013 when oil prices were around $100/bbl but development costs had increased to $20 billion. BP and its partners, BHP Billiton, and Chevron Corp., cut the costs to $9 billion with the redesign, making the project feasible in the current price climate.

This approach will recover fewer reserves, at least from the initial project, but makes development economically feasible.

Phased development

Phased development is not a new concept. Petrobras Energia SA has done it for many years in Brazil's subsalt plays. Developing one portion of an area provides operators an opportunity to observe reservoir performance, develop a learning curve for well design, and access cashflow that can fund subsequent phases. Recent examples include ExxonMobil's Liza project offshore Guyana, on which the company expects to make a Phase 1 final investment decision (FID) this year.

The flexibility and lower capital allocation required for a phased approach will set a trend for deepwater projects into the next decade, according to Wilson,

Subsea solution

Wood Mackenzie expects a move to subsea tiebacks to be one of many drivers toward a smaller, more efficient profile for the market going forward. In places where infrastructure is plentiful, using available capacity makes sense. "The Gulf of Mexico is marked by high levels of cooperation," Wilson said. Block sizes in the US Gulf place operations in close proximity to one another, which makes collaboration more feasible. Julia and Buckskin are two examples of large fields that were initially envisaged as standalone developments but were redesigned as subsea tie-backs.

Operators of platforms have the opportunity to develop nearby satellite discoveries into their own infrastructure at low cost. Anadarko operates multiple developments across the US Gulf and has a proactive 'hub and spoke' strategy. At a time when capital discipline rules, companies have become more interested in smaller tie-back fields.

Total projects, including subsea, are down compared to 2010-14. Despite the increased use of subsea tie-backs to cut costs, the "size of the subsea sector will not return to historical high levels before the end of the decade," said Wood Mackenzie research manager Caitlin Shaw. Opportunities will be there, but they will look different than before the downturn.

Cost reductions, efficiency

Cost reductions in new developments are due in part to deflation, not least in rig rates. Operators not bound by longer-term rig contracts are picking up deepwater rigs for less than $200,000/day, a third of 2010-14 rates. "Not all operators have that advantage, but as we move forward in time more long-term contracts will roll off," Wilson said. Many operators will manage to renegotiate rig rates or release rigs early.

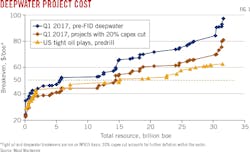

With fewer wells drilled, more rigs are out of service (Fig. 2). More than 75 floating rigs have been permanently retired since the end of 2014. The majority (75%) were retired in 2015. "There are still more than 80 floating rigs that are 20-45 years old and nearly 70% of those rigs are not currently working," said Leslie Cook, senior research manager, Wood Mackenzie. "More than 50 additional rigs will be retired within the next 2 years."

Drilling speed and rates of penetration have risen in the last couple of years, after several years of slower drilling. Transferring lessons learned from tight oil, operators have streamlined logistics and eliminated redundancies. They are also designing simpler wells with fewer casing strings. Dual-gradient drilling is reducing drilling time and blowout preventers (BOP) are changing out at faster rates. Overall drilling operations are much more efficient than they were.

"Even with rates at $500,000/day or more on some rigs, we're seeing well costs come down," Wilson said. With more rigs retiring, drilling companies have retained only the most experienced crews to operate those that remain. Automation has also helped reduce manpower (and costs) on rigs, and speed up operations.

Operators are seeking to lock in the drilling efficiencies gained through the downturn to mitigate natural cost inflation should oil prices recover.

Seismic companies have struggled financially. In some cases, the price tag for a seismic shoot is 20% of the pre-2014 price.

Operators are taking advantage of low prices by buying multiclient seismic data, but consolidation remains a concern as less competition is not favorable for the industry. "Operators are interested in keeping costs low, but they also want seismic contractors to survive this downturn," Wilson said.

One bright spot is that operators are increasing use of 4D seismic using ocean-bottom nodes to maximize recovery from existing fields. In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, 4D has illuminated smaller deposits left behind during early development of Shell's Mars field. These can be accessed through new infill wells. "These opportunities have very low breakevens because infrastructure is already in place and [the operators] understand the geology," Wilson said.

Some of the areas that have previously seen high levels of deepwater activity, particularly Angola and Nigeria, have stagnated since the oil price collapse. "Looking back to 2014, when oil prices were still high, there were a lot of potential projects in Angola and Nigeria," Wilson said. However, deflation and cost savings have been more difficult to achieve in West Africa, leaving many developments on the drawing board.

Development projects

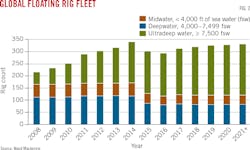

Royal Dutch Shell PLC subsidiary, Shell Offshore Inc., in February 2017 made an FID on Phase 1 of the Kaikias deepwater discovery. This project is a phased subsea tie-back, bringing two trends together.

The near-field opportunity will produce oil and gas through a tie-back to Shell's Ursa production hub. Shell said Kaikias carries a breakeven price of below $40/bbl. The operator cut total cost by about 50% by simplifying development design (Fig. 3). Shell will develop Kaikias in two phases. Phase 1, which includes three wells designed to produce up to 40,000 boe/d, will start production in 2019. Kaikias is in the prolific Mars-Ursa basin about 130 miles from the Louisiana coast and is estimated to contain more than 100 MMboe of recoverable resources.

Mad Dog and Kaikias are two of three deepwater projects moving forward in 2017.

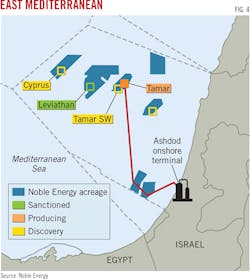

Noble Energy Inc. has begun first-phase construction on its giant Leviathan natural gas field offshore Israel in the Mediterranean Sea (Fig. 4). Noble has drilled four wells, which will be completed subsea in about 5,200 ft of water (OGJ Online, Mar. 2, 2017). Noble estimates gross capital costs for Phase 1 development at $3.75 billion and gross reserves related to the investment at 9.4 tcf of gas. Leviathan holds gross recoverable resources of 22 tcf.

Production from the first phase is to start by end-2019 at 1 bcfd. A second development phase would add 900 MMcfd from four new wells, two processing trains, four compression trains of 300 MMcfd each, and a third tie-back flowline.

Exploration

Senegal and Guyana have recently yielded giant deepwater discoveries in frontier basins and these projects will move forward. Frontier and emerging provinces will continue to attract activity but at a slower pace than pre-2014. Deepwater exploration and development are long-term and require commitment from senior management to stay the course.

Deepwater exploration will remain lower than before 2014 (Fig. 5). "We are also likely to see smaller discovery volumes," Wilson said. Companies will apply greater commercial focus to exploration. Most wells will target prospects that can be produced quickly upon discovery.

Well risk is also increasingly a factor in prospect decisions. High pressure-high temperature reservoirs involved more drilling risk, and took longer to drill at a higher cost. Operators have sought to simplify well designs and are now more risk-averse, both in well design and in selecting geologic targets.

Beginning in 2014, exploration started to shift towards a focus on value rather than adding volume. Most operators in 2017 seek prospects that can be developed at $50/bbl in the event of success. Exploration likely will take on a smaller role in reserves replacement as companies look to other mechanisms to deliver reserve and resource growth.