Discipline, simplicity crucial for project execution overhaul

Matt Zborowski

Staff Writer

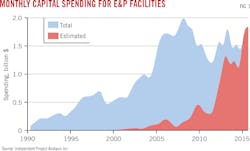

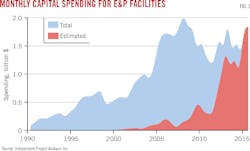

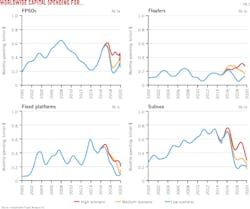

Aided by a plunge in crude oil prices from $100/bbl in summer 2014 to less than half that level at this writing, the oil and gas capital project market-particularly in the exploration and production space-has dropped off dramatically since a peak in activity during 2012-13. Both project owners and contractors have responded to the distressed market with large cuts in capital spending and personnel, leading to the slowing, delaying, or outright cancellation of projects that are needed to sustain the industry.

The primary difference between now and the industry's more prosperous times is that the margin for error is so much smaller and mistakes are far more visible. What companies could afford to overlook when oil prices topped $100/bbl has become a barrier to success at $40/bbl. Owners and contractors have therefore been forced to fundamentally change the way they do business, but only time will tell if they are changing for the better.

In their quest to improve project efficiency and execution, owners and contactors have taken to enlisting the services of advisory firms such as Independent Project Analysis Inc. (IPA), whose portfolio of more than 20,000 projects from more than 50 operators has given its leaders unique insight into the project market.

How we got into this mess

Speaking with Oil & Gas Journal, leaders of IPA explained that the issues plaguing the current project market were years in the making. During 1985-2003, when crude prices ranged $11-36/bbl, project activity was low, and, like today, owners sought to cut costs.

This involved downsizing their in-house project organization, with the reduction or removal of core competencies such as estimating and engineering.

When it came to working with contractors, owners started to forgo strong working relationships, forged by positive project results and repeat contracts, by instead awarding contracts merely to the lowest bidder. Many engineering, procurement, and construction firms were driven out of business during this time period.

As crude prices rose, firms fell into the habit of chasing volume over value, focusing on maximizing production from the outset, or "chasing barrels" and net present value (NPV). At the same time, project costs shot up, reserves depleted quicker, and projects lost profitability down the road.

In the ensuing decade to 2013-14, capital expenditure per barrel increased well beyond inflation, with asset cost per barrel multiplying by four, according to IPA data. The firm notes that well costs tripled, pipelay costs shot up 60%, detailed engineering costs doubled, and subsea kit costs tripled.

Koen Vermeltfoort, partner at McKinsey & Co., a global management consulting firm that advises oil and gas clients throughout the supply chain, told OGJ that costs for large projects doubled-to-quadrupled on a per ton basis from the early 2000s to 2014. "A significant part of that increase can be explained by higher-cost locations," he explained.

The overall lack of discipline has given way to increasing project complexity, worsened by additional issues such as logistical constraints and the challenges presented by the unique political and social climates of different regions.

Trimming the 'bloat'

"Portfolios are pruning projects in these [higher-cost] locations, resulting in portfolio cost reductions," Vermeltfoort said. "On individual projects, we see that project teams [that] are systematically revisiting project scopes and specifications are reducing cost [15-30%] on average."

Scopes have been "very bloated" for a while for upstream projects, said Neeraj Nandurdikar, IPA director of oil and gas practice. He explained that, in particular, Western companies for a long time have been conditioned to pursue NPV and volume. This requires more complex facilities and systems, bringing in more fabricators, for example, which in turn introduces more cost into the process.

"Firms that [merely] focus on 'cost-savings' go for the short-term, low-hanging fruit," he said. It's difficult for those companies to forgo extra barrels, but "now producing expensive barrels is more difficult," he said. Asked Nandurdikar, "How do you reframe the way you operate when you've never experienced such a downturn?"

He said smart firms are now looking at "lean-scoping" whereby they examine whether they want to develop for the peak of the project or for the long term. While such a focus on sustainability varies by company and project type, it requires that all companies take a simple, more-measured approach in developing their projects. He added, "Why produce everything at once?"

Ed Merrow, IPA president and chief executive officer, cited as examples two owners that have had success executing large-scale projects. "Anadarko [Petroleum Corp.] has been an excellent projects company for a long time," he said. "They have developed a strong supply chain for deepwater spar facilities that is genuinely unique and excellent."

The other is BP PLC, which he said "learned the right lessons from their disaster at Macondo and started the process of strengthening and simplifying their projects before oil prices started to dip. That has given them a head start over their peers."

Moves by contractors

Providing a contractor's perspective, Graham Hill, KBR Inc. executive vice-president, global business development and strategy, noted that recent cost-saving measures from his space have included the usual "rate reductions, salary reductions, personnel benefits suspensions, staff severance, reorganizations, and early retirements-to name a few."

However, he also mentioned low-cost engineering centers, low-cost sourcing, and modularization as "tangible steps for global contractors to generate value for customers in these challenging times." Low-cost engineering centers include India, Thailand, Philippines, Mexico, and Eastern Europe.

"This has become part of the global commercial fabric, and is built into every global contractor's capability," Hill said. "It has become standard for the business, and has now been mandated by owners, who are pushing for 'best-cost solutions.'"

He said, "In more recent years-say, the past 5 or so-low-cost sourcing [such as equipment, materials, and fabrication] has ramped up globally to provide cost-effective solutions for world-class projects. Examples would be LNG and unconventional gas plants in Australia, which have been masterminded by the global contractors, with the majority of the fabrication and a good deal of equipment and materials sourcing coming from China." In particular, he added, "China has improved its delivery reputation over the period to become equivalent to the best in the world-equivalent in quality to Korea-and at a much lower overall cost."

Shoddy engineering

The performance of EPC firms is "very much a function of how warm the market is," said Merrow. In addition to recent layoffs, EPC firms are losing experience to retirement "at a catastrophic rate." That lack of experience is manifesting through engineering error, which Merrow said has doubled since 2007.

IPA says that every measure of engineering quality has fallen since 2008, including error rate, productivity, and engineering slip, the latter of which is approaching an average of 40%. "The most serious problem facing capital projects is in timely and accurate engineering," IPA asserts, and "large-project EPC contractors are struggling to perform."

The firm believes "the supply chain has too many weak links" resulting in an all-time low in work quality. Large project contractors also are struggling with engineering deliverables, making procurement systematically late or out of sequence; and home office-value center interfaces that are often slow and inflexible.

Exacerbating the problem is the rush for EPC firms to begin field work, regardless of their actual level of readiness. Mistakes early in the process lead to even more mistake further in the project, killing NPV.

IPA says owners need to understand what constitutes reasonable engineering hours, learn to measure engineering progress, and know when the work is being done inadequately; discuss with fabrication yards how owners and EPC firms can boost productivity; move to open thin vendor markets; and discuss local content expectations with governments.

Brace yourself: 'standardization'

An often-mentioned solution to poor engineering is simplification and thus standardization. The oil and gas industry has long paid lip service to the virtues of standardization, but actual action to standardize engineering practices has been rare given the unique complexity of each project and the inability of many engineers to come to a consensus on the best standardized procedures.

IPA notes that standardization requires long-term planning and discipline, and should cover the entire supply chain from owner functions to contractors to vendors. Early and continuing operations input is essential to successful standardization, and earlier well planning involvement is necessary to balance the adverse effects of standardization on well difficulty.

Luke Wallace, IPA associate director, PRD cost analysis, said, "The idea of standardization in upstream projects has been talked about for years," but hasn't been fully realized by the upstream segment. "The reality is that industry has no choice" but to standardize if they want to improve efficiency. When done right, companies will beat the market by 20-25%, he said.

In an IPA survey of 35 owners and suppliers, more than half of owners and more than 90% of all contractors agree that contractors are ready for standardization, but owners are unwilling. Owners have long focused on each project as a "unit," to ensure-with its specific challenges in geology, environment, and scope-it's optimized for the present.

One oil and gas industry chief executive officer expressed his frustration to IPA on talk of standardization, "I think if I hear the word standardization [again] I am probably going to go nuts…we have been talking about this for 3 decades…yet it's eluded us until maybe now." An industry vice-president said, "There will be standardization in oil field developments the day there are standardized oil fields…ergo…never."

Jeff Reilly, group president of strategy and business development of Amec Foster Wheeler PLC, noted that standardization has been effectively implemented in the US midstream market, "where technical standards are less-stringent than in some other oil and gas sectors." He explained that as output of liquid and gas hydrocarbons increased in recent years, infrastructure had to be built quickly to get it to market. Helping the cause has been standardization of compressor stations in new pipeline builds.

"Also, standardized designs have been used for rapid building of new liquefied petroleum gas fractionation plant capacity on the Texas Gulf Coast," Reilly added. "We believe these trends will continue and we are working with our customers to effectively find ways to standardize more."

Axel Preiss, Ernst & Young global oil and gas advisory leader, had a more optimistic outlook on the topic while speaking with OGJ. Noting that "an enormous number of projects are not delivering on their promise," he believes "standardization absolutely will happen" in the oil field with the help of software tools and big data. This should also come with a reduction of costs on the procurement side, he said.

Regarding the experience and knowledge gap arising from mass layoffs and retirements, Preiss has a different perspective, mostly seeing it as a nonissue for the long term. "Digital trends seen in other industries are impacting oil and gas," he said. Advancements in areas such as data capture and automation will result in the permanent elimination of many of those lost jobs. "The job descriptions of the next generation will be very different from this one's," Preiss predicts.

Vermeltfoort said he's observed "EPC firms using a number of digital applications, ranging from spatial scanning (LIDAR), virtual reality sequence, and logistics simulations to real-time progress tracking versus schedules." He added that the infrastructure space is ahead of oil and gas in this regard, which he believes is driven by the difference in push and demands from the owners.

Owner-contractor relations

When it comes to executing projects at the owner level, what companies routinely don't do, Merrow said, is clarify project objectives, have adequate representation in project teams, and complete front-end work. That's when the project unravels. Most problems created by the project owners are transferred to EPC firms.

Vermeltfoort said, "There are operators who are actively working with suppliers to effectively design out cost and waste by running lean construction programs with their EPCs and by building a supply ecosystem that can capture cross-project benefits and learning curve."

Reilly emphasized "a continued need for capital efficiency beyond mere cost-cutting to ensure that the industry is sustainable moving forward." Even as "capex and financing constraints are driving a more cost-focused contractor selection," owners "still want to know that when they start up their facility, it will perform as expected and deliver the anticipated revenue stream when they expect it," he said.

Many owners are "revisiting the overall concept or configuration for their planned investments, either to reduce the overall cost, or to establish a phased development plan," he said. This is particularly true for the upstream segment, where "there has been a shift from 'schedule-driven' to cost-cashflow-driven," he said.

"This is an activity in which our consultancy teams often play a key role," Reilly said. "Where we can establish a relationship with a customer at the earliest phase of the development of a planned investment, we are able to understand their business drivers and objectives and help them shape their investment having looked at many different solutions."

He said owners and contractors in the industry are examining alternative execution, such as "modularization vs. stick build, industry vs. customized standards, standardization vs. everything custom, reducing overdesign." He added that both sides are "really questioning what activities add value or are required for compliance."

Reilly said, "Increased openness and information-sharing between customer and contractor is one of the key success factors for our industry going forward, and ultimately pays dividends in what can be achieved to meet business objectives with constrained capex budgets."

Contract trends

As for the contracts themselves, Hill noted that "there is definitely a shift towards EPC contracts-lump-sum, fixed-price-and moving of risk from owner to contractor." He said, "Owners are also downsizing, understandably, and outsourcing with more onerous terms, taking advantage of the depressed services sector."

Reilly said owners are "looking to shift additional contractual risk onto the supply chain and increasing the amount of fixed-priced scopes of work." He added, "Centrally led procurement initiatives are looking to capture the deflation across the value chain."

Merrow has observed that EPC firms "are very reluctant to take on EPC lump-sum contracts because they are-probably rightly-concerned about their ability to deliver on them." When those contracts go bad, EPC firms become subject to "mortal danger," he said.

"There are advantages to operators that know how to manage contracts divided between engineering and procurement on one hand and construction on the other," Merrow explained. "Owners can use reimbursable contracts for engineering, which is a smaller part of the job and difficult to lump-sum anyway and then get better lump-sum bids for construction."

He said, "Construction-only lump-sum contracts are not viewed as being nearly as risky by contractors as EPC lump-sums. Instead of the performance period being 3½-5 years for EPC, it is usually more like 2-2½ years for construction. Time is viewed as the riskiest of all variables by contractors because predicting the future is a fool's game."