The price of oil and OPEC-history repeating?

Manouchehr Takin

International oil and energy consultant

London

Ramin Takin

Parkway Logic Ltd.

London

The world oil market today is characterized by a standoff between the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers amid excess supply. Financial markets, speculators, and conspiracy, however, may have played a role in creating this standoff. In the currently weaker oil-price environment, market players are waiting to see who will blink first.

In this article we seek to draw some lessons from the past in order to shed light on nuances in oil market fundamentals, as well as present some views on OPEC's response patterns.

Lessons from the past

While there are other occasions when OPEC either has decreased or increased its production levels in response to changing conditions in the world oil market, we will examine three cases of drastic drops in the price of oil: 2008, 1998, and 1986.

Oil prices fell in late 2008 amid a drop in world demand following the global financial crisis and economic contraction. Oil prices fell from nearly $150/bbl in July to about $40/bbl by late 2008-early 2009.

Another case, in 1998-99, was due to both excess supply and weaker demand. The excess supply followed OPEC's decision to increase its production quotas at a Nov.26 - Dec. 1, 1997, meeting in Jakarta.

The decision to raise production rates was attributed to a standoff between Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. The latter had been producing above its OPEC quota for about 4 years, while Saudi Arabia and other members generally had curtailed their production over that period.

While the Jakarta decision to raise production quotas remedied that situation, higher OPEC output coincided with economic crises in the Far East and Russia, as well as a drop in oil demand. Oil prices, consequently, fell to less than $10/bbl from about $20/bbl.

A third case of a major decline in the price of oil occurred in 1986, when increased supply coincided with weaker demand. Much like current market conditions, a sustained period of high oil prices created competitors for OPEC, with non-OPEC producers increasing production levels.

Preceding this period, the price of oil rose to $11/bbl from $3/bbl in 1974, and to more than $35/bbl by about 1980. Bumper oil and gas industry revenues helped expand field operations around the world and subsidized the development of new technology, resulting in a rapid increase in global oil production.

By the early 1980s, however, the aftereffects of the 1974 and 1980 price spikes contributed to a sharp decline in demand for oil, with demand particularly weaker for OPEC oil.

OPEC defended high oil prices by cutting its production at different intervals during 1980-85, reducing output from OPEC-member countries to less than 15 million b/d from about 30 million b/d.

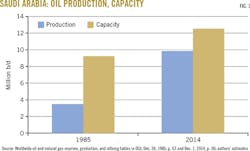

Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia incurred the greatest production losses. By 1985, about 60% of its production capacity was idled (Fig. 1).

After setting the price of oil since late 1973, in late 1985, OPEC announced that it would no longer reduce its production in support of prices and that it would start netback pricing, i.e., letting the market decide the price of oil. Oil prices, as a consequence, fell to less than $10/bbl from nearly $30/bbl.

Some observers described OPEC's action as a price war with non-OPEC producers.

Industry stress, political pressures

In the 1986 and 1998-99 cases, OPEC called on non-OPEC producers to cooperate in helping stabilize the market by reducing their production. Meetings took place between the two groups of producers, as did a flurry of discreet and open lobbying of OPEC by world politicians. Actual significant cooperation by non-OPEC producers, however, did not materialize, despite statements and promises by various non-OPEC-member governments.

The lower oil-price environment eventually made high-cost production areas unprofitable, reducing cash flows for oil companies and forcing them to scale back activities. Service companies, manufacturers, suppliers, and subcontractors suffered from the loss of major contracts and were forced to downsize. Many oil and service companies went bankrupt, and there were extensive layoffs across the global oil industry.

Surviving companies had to lower their exploration and capital expenditures, delay developing new fields, and even reduce investments in maintenance for existing production fields.

Notable lessons

Although measures by the industry to scale back spending resulted in a slowdown in the growth of-or sometimes an actual decrease in-oil production, it took several months, and sometimes more than a year, to establish a new supply-demand balance.

Expensive offshore platforms and major onshore production installations, for example, continued to operate because owning companies treated their capital outlay as a sunk cost and because their operating cash outflow was still below the price of oil.

The impact to production occurred more quickly in cases where operating costs were too high or required more frequent capital expenditure. Many stripper wells, for example, were closed when they became due for costly maintenance work.

The massive redundancies, recession, and crises in almost all world oil provinces also forced politicians to act. In 1986, for example, US Vice-Pres. George Bush visited Saudi Arabia to meet with King Fahd bin Abdulaziz al Saud. Again, in 1998-99, US Secretary of Energy Bill Richardson openly lobbied OPEC, including visits to some of its countries to meet with oil ministers.

In order to restore balance to the world market, OPEC eventually deemed it necessary to reduce its own production, choosing a lower production ceiling and allocating smaller quotas to its members.

The combination of OPEC's decision to curtail production and the fall in oil prices resulted in some actual reduction to both OPEC and non-OPEC output.

But the effects of reduced production were not immediate. It took more than a year before the world market stabilized. This was particularly the case when the decision to cut production had been delayed and excess supply had gone into inventories around the world, filling both onshore and offshore oil storage. The price of oil remained low until these inventories shrank to more normal levels, when it finally settled lower compared with prices before the crisis.

Recent conditions

The oil price collapse in late 2014 appears to be broadly similar to previous price downturns. An imbalance appeared in the oil market, principally due to excess supply, and the price of oil fell sharply.

Underinvestment in the global industry occurred from 1998 until about 2004 because industry decision-makers took years to gain confidence that the price of oil would not again fall back to $10/bbl or lower, as it did during the 1998-99 price collapse. Given the several-year lead times of upstream operations, when the industry did finally start to increase investments in the mid-2000s, supply could not catch up with years of strong growth in world oil demand (e.g., China's economy).. Fear of a peak-oil crisis and new developments in financial markets accentuated these factors, helping prices rise to nearly $150/bbl by July 2008.

Excess supply, weak demand

In recent years the reverse has been happening, as the industry's field activities began to result in higher production, prompting the current oversupply and thus a reduced need for production from OPEC, the residual supplier. The accompanying table shows annual changes in world oil demand and supply met by non-OPEC producers during 2011-14.

Sustained prices of more than $100/bbl since the late 2000s encouraged major investments in high-cost areas and the application of new technology around the world, including US shale and tight rock plays, offshore West Africa, and onshore-offshore East Africa.

Another important but often unrecognized reason for surplus oil supplies is improved performance of many older producing fields around the world due to the application of new technology. Production declines at these aging fields have slowed, and in some cases, actually been reversed.

Social unrest, wars, lack of security, and the imposition of sanctions (e.g., Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, and Iran) kept some notable oil producers out of the world market over the past few years, but not enough to compensate for the surplus. And as conditions in some of these areas have improved, more oil has reentered the world market.

Global oil demand has been growing more slowly than supply due to weak economies in Europe, North America, Japan, China, and other regions. The global economy also has improved its energy efficiency and is using less oil by substituting other energies.

These factors put downward pressure on oil prices. Producers hoped OPEC would follow precedent and cut production to defend the price of oil.

In an echo of the past, OPEC called on non-OPEC producers to cooperate with it. In late 2014, oil ministers of Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Mexico, and Russia met to discuss market conditions and the need for cutting production. Mexico and Russia, however, did not agree to cuts.

A few days later, on Nov. 27, 2014, OPEC ministers decided not to cut production quotas for member countries, either.

Reflecting on the experience from the first half of the 1980s, Saudi Arabia feared it would be forced to leave much more than the current 2.7 million b/d of its production capacity unused (Fig. 1).

Saudi Arabia's oil minister has stated that OPEC does not want to keep losing market share and that he is not concerned with falling prices, even if they reach $20/bbl.

UAE's oil minister, meanwhile, said that producers of shale oil and other non-OPEC production were acting irresponsibly. OPEC's strategy is to gain, or at least preserve, market share, setting up a price war similar to one that occurred in 1986.

Moving ahead

There has to be a political solution with pressure on Saudi Arabia and the other wealthy OPEC members, both from within OPEC (Venezuela, Nigeria, Iran, Algeria, and others) and from outside. Outside pressure, however, so far has not been very effective.

The fall in oil prices should improve the trade balance of net oil-importing countries, and cheaper fuels should strengthen their economies. These countries, however, will face difficulties in the short-term.

The banking sector could face problems due to high exposure to some parts of the oil sector and a concern that many producers need $100+/bbl prices to sustain their large debts. This is particularly true of many medium and small exploration and production companies, as well as service companies, suppliers, and manufacturers exposed to high-cost operations.

The fracking companies may be under the greatest financial stress. Their breakeven costs range from $30-70/bbl, but their heavy gearing (e.g., using a high proportion of bank debt to finance asset acquisitions) makes even the lower-cost operators vulnerable.

International trade also is suffering because of the drastic cut in revenues of oil-exporting countries and the subsequent sharp reduction of their imports from Europe, North America, Japan, and other OECD countries. Countries heavily exposed to the oil and banking sectors could experience further recessionary pressure, unemployment, and social stress.

As on previous occasions, almost all major and independent oil companies around the world have announced notable reductions of their exploration and field development budgets for 2015, as well as redundancies and other cost cutting measures.

These will result in lower oil production later in 2015 and, more noticeably, in the following years. Oil production declines could occur sooner where operating costs are high or where relatively heavy investment is required for production maintenance or for drilling new wells to maintain rates of production. Fracing operations for shale and tight formations fall into this group, as do stripper wells.

High-cost operations with relatively short lead times, some highly leveraged, constitute a relatively larger share of world oil supply today than in 1986. Some operators are finding breathing room by negotiating lower prices with service companies, continuing to improve their operational efficiency, and by virtue of current low-interest rates. Nevertheless, these are not enough to protect them from the realities of the oil market.

Concerns exist that productivity of wells fracked in existing formations may not be as high as the early wells focused on sweet spots. Highly leveraged operators may also find themselves out of favor with the financial sector, leading to a more rapid reduction of non-OPEC oil production than occurred in 1986.

Some OPEC members (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar), however, can tolerate an extended drop in oil export revenues, as they could draw on healthy reserve funds or use their strong credit position to secure finance from the international banking system.

Other OPEC members, however, have smaller financial reserves, larger populations, and already are suffering from budget deficits. These countries cannot withstand the loss of oil revenues for long, creating tensions within OPEC.

Saudi Arabia has the largest oil production capacity in OPEC (12.5 million b/d), with nearly 3 million b/d already unused. While this gives Saudi Arabia the flexibility in principle to increase production and partly compensate for lower prices if world oil prices do not recover to $100/bbl levels, other member countries already are producing near their maximum capacities. Some are above and some are below their theoretical production quotas because of technical problems, imposed sanctions, politics, and lack of security. They cannot compensate for the fall in prices by increasing their oil exports.

These countries are putting increasing pressure on Saudi Arabia to lower its output, raise the price, and provide them with much-needed oil revenue.

These intra-OPEC negotiations will eventually involve heads of state capable of overriding the business decisions of their oil ministers and cutting production. Saudi Arabia may have to incur the greatest cuts.

Pressure on politicians in the non-OPEC world also is building. Non-OPEC producers have reduced output in the past. The Texas Railroad Commission, for example, imposed smaller production quotas on oil companies in 1930-32 in response to the Great Depression (OGJ, July 28, 2003, p. 31).

The current low-price regime will result in some reduction of production in non-OPEC regions, but it will be insufficient to raise the oil price to near its previous levels. Political pressure on OPEC to cut its own production will rise, principally focused on Saudi Arabia and coming from both non-OPEC and OPEC countries. At the time of this writing in January, we estimate this will not occur before autumn 2015 and could occur much later.

If history repeats itself, the price of oil will begin to rise until the market gradually stabilizes at a price lower than before the current crisis. The lower price, then, will encourage higher consumption, prompting increased global oil demand. Higher demand, in turn, will lead to higher prices and more field activity, which will increase supplies, and consequently, add downward pressure on oil prices once again.

OPEC's future

Extending the prognosis further, OPEC ultimately will decide to lower its production ceiling and allocate new quotas to its members. This reversed course, however, will not mean the organization is irrelevant, nor does it spell the end of OPEC.

Similar market conditions have occurred in the past. In spite of its shortcomings, OPEC is the only institution of commodity producers in the developing world that has its leaders meet regularly, its secretariat conduct systematic research and market and policy analysis, and that has been in existence for more than 50 years. It was established to strengthen the bargaining position of the producing countries against the majors' hegemony over the world oil market, the price of oil, and the volume of production from each country.

OPEC may not have been nearly as successful as it was in its early days had it not been for new independent oil companies giving OPEC producers credible partnering alternatives to the majors.

The industry, the world oil market, and the role of OPEC have evolved over the decades. The price of oil is now decided by the market. While OPEC no longer determines the price of oil, it tries to ensure the price is reasonable for its purposes and that the market is stable, even though it may be difficult to define these goals.

Tensions within the organization will not eliminate OPEC's influence on the market in the near term. Member states have but to look at the fate of many other commodity producers, which have a much weaker bargaining position and have needed fair trade activism by consumers to help them receive reasonable revenue, to be reminded of the perils of diminishing their strength.

It is probably with this in mind that OPEC is exercising its influence now, in an echo of its actions from 1986.

The authors

Manouchehr Takin ([email protected]) is a London-based independent global oil and energy consultant. He was with the Centre for Global Energy Studies in London during 1990-2014, where he examined technical and economic aspects of world oil supply and demand, OPEC policy, investments, among other topics. Before joining CGES, he worked for 9 years at the OPEC Secretariat in Vienna after careers with Iran's International Oil Consortium, Amoco, Ultramar, National Iranian Oil Co., and Shell, as well as the Geological Survey of Iran and Anglo-American/Charter Consolidated. Takin holds a BS in geology from Manchester, a PhD in geophysics from Cambridge, and an MBA from Industrial Management Institute, Tehran.

Ramin Takin ([email protected]) is an energy finance professional and start-up co-founder. He was vice-president of corporate finance and development at Unaoil Group after serving as managing director and risk manager at Essdar Capital Ltd. Takin began his career at Citigroup in London. Ramin holds a PhD in quantitative finance from Imperial College, London in 2005, and a masters in engineering, economics, and management from University College, Oxford University, in 2001. He is an associate member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.