East Mediterranean Development-2 Narrowing opportunities require cooperation

Shaul Zemach

Independent consultant

Tel-Aviv

Neighboring East Mediterranean states hold a mutual interest in economic developments resulting from new hydrocarbon resources. These interests should be harnessed to enhance security, increase stability, and accelerate political dispute resolution within the eastern Mediterranean.

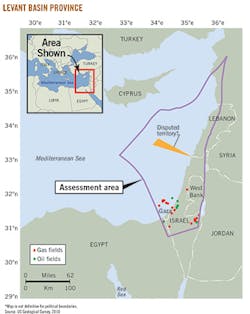

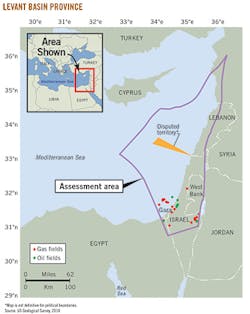

The extent of the Levant basin and the distribution of its fields require substantial investment to reach full economic potential. Limited regional demand also calls for integrating exports into field development plans if the Levant is to reach full potential. The region's many conflicts, however, have removed basin-wide hydrocarbon development as a possibility.

The second best alternative is to explore various degrees of interstate cooperation regarding joint pipeline and processing infrastructure to increase the efficiency of developing these resources. Although this alternative is less desirable, neighboring East Mediterranean states must reach a certain level of cooperation to benefit from their domestic hydrocarbon resources.

Opportunity narrows

Decision-making regarding Israeli export infrastructure defines the time frame for this second-best alternative. Israel's window of opportunity for finding a viable strategy to export its resources is closing and soon may be sealed.

Potential reserves in the Levant basin exceed eastern Mediterranean demand. The required investment is not justified by domestic demand in Cyprus and Lebanon. Liquefaction technology, either floating or onshore, would have allowed development in Israel. This option, however, is off the table after the country's disengagement from Woodside Petroleum Ltd., Australia's largest LNG producer.

In May 2014, Woodside advised Noble Energy Mediterranean Ltd., Delek Drilling LP, Avner Oil Exploration LP, and Ratio Oil Exploration (1992) LP that negotiations between the parties in the Leviathan joint venture failed to reach the commercially acceptable outcome necessary to have executed fully termed agreements (OGJ Online, May 21, 2014).

Each regional state needs the cooperation of at least one other to develop alternatives for gas export. The combination of low domestic demand, small-scale future expected natural gas deposits (Leviathan and Tamar fields being exceptions), the dispersal of resources throughout the region, required heavy investments, and weak economies create the need for cooperation to gain efficiency. In some cases solving this puzzle is a precondition to developing exploration and production in national exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

Developing export infrastructures in the eastern Mediterranean is part of a wider perspective and requires more cooperation between neighboring states.

Current initial pipeline plans from Israeli discoveries to Turkey would cross the Cypriot EEZ to avoid Syria's and Lebanon's EEZs. It is unlikely Cyprus would allow such a scheme without substantial progress in its reconciliation process with Turkey and a clear vision of its share in the gains.

Cyprus Pres. Nicos Anastasiades, said that after a solution, in parallel with the targeted construction of a liquefaction plant near Limassol, Turkey could be supplied with Cypriot and Israeli natural gas either via a pipeline through Cyprus's EEZ or across the island.1 A number of Turkish companies have already visited Cyprus and met with the foreign ministry and energy ministry to explore these options.

The president of the Republic of Cyprus clarified the country's position that Turkey could become a client for the region's natural gas but not a strategic partner. Cyprus is willing to export gas to Turkey but not to partner with it on reserve development.1

The Aspen Institute suggested in 2012 that an investment environment for developing natural gas in Lebanon would require both a clear maritime boundary based on established international law and agreements and a profitable export framework not blind to the challenges of regional cooperation. The theoretically attractive idea of a joint Israeli-Lebanese LNG liquefaction plant and export terminal is, for example, out of reach.2

Given these impediments, it is reasonable that Noble Energy and its partners sought a self-sustained floating LNG plant. This alternative, however, is no longer technologically or commercially feasible.

Regional obstacles

Impediments imposed by regional disputes among several neighboring states in the Levant basin complicated its successful development. Geopolitics in the eastern Mediterranean compound infrastructure problems associated with resource development.

Israel-Lebanon

Lebanon and Cyprus in 2007 signed an agreement on the delimitation of their respective EEZs. Cyprus ratified the agreement but the Lebanese parliament did not.3

A Cyprus-Israel maritime agreement followed the Lebanon-Cyprus maritime agreement.

Cyprus and Israel finalized their agreement in December 2010 and submitted it to the United Nations (UN) on July 12, 2011, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

As part of this process, Lebanon deposited with the UN Secretary General charts and a list of geographic coordinates of its southern boundary with Israel and its southwestern boundary with Cyprus. These unilaterally declared maritime boundaries, however, differed from those in Lebanon's 2007 agreement with Cyprus.

The so-called "Point 1" on the map set as a shared dividing point between Lebanon and Cyprus in 2007 differs from Lebanon's 2010 maritime boundary submission which used a different coordinate, "Point 23," 17 km southwest of Point 1 and overlapping an area claimed by Israel (Fig. 1).4

Lebanon's government claimed that, based on its interpretation of the Cyprus-Lebanon delimitation agreement from 2007, the Israeli geographical coordinates violate the sovereign and economic rights of Lebanon by cutting 860 sq km from its territorial waters and EEZ.5

Head of Lebanon's Public Works and Energy Committee Mohammad Kabbani told NOW Lebanon that using Point 1 was a mistake and that the agreement was supposed to have left Lebanon's southern boundary open for negotiation.6 Lebanon's parliament never ratified the agreement for fear of angering Turkey, which occupies part of Cyprus and does not think the Cypriot government has the right to negotiate such deals, Kabbani added.

The competing claims over maritime territories are a source of instability and an obstacle that must be lifted to promote exploration in the disputed areas. Most international oil companies would be hesitant to operate without a maritime border treaty.

Israel has not approved any operational activities in the disputed area. Lebanon, however, included Blocks 5 and 9, containing some of the disputed zone, in its latest bid round. The country did not place formal claims regarding Tamar and Leviathan reserves.

The US has worked on resolving the competition. In September 2013, Frederick Hoff, US special coordinator to the Middle East, and Amos Hochstein, deputy undersecretary for energy diplomacy, acted as mediators between Israel and Lebanon on the issue, drawing suggested lines based on established international law and precedent cases.

Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, meanwhile, has called natural gas platforms in the Mediterranean legitimate targets. The Israeli working assumption is that Hezbollah has the ability to cause extensive damage to platforms and to Israeli vessels, as well as to ports and other vital installations, and the country is increasing its naval power better to secure its hydrocarbon assets.7 The Israeli navy is paying particular attention to Hezbollah threats to use Russian Yakhont shore-to-sea missiles in its attacks.

Domestic politics will determine future progress.

Turkey-Cyprus

Turkey refuses to recognize the agreements on maritime borders Cyprus has concluded with other neighboring countries and has gone as far as to threaten to deploy warships to prevent drilling for gas in the Cypriot EEZ. On July 31, 2013, a Turkish naval vessel fired a warning missile at Odin Finder, a cargo ship flying the Italian flag, managed on behalf of the Cyprus Telecommunications Authority.8

On Feb. 13, 2014, the permanent representative of Cyprus sent a letter to the UN Secretary-General, claiming that "the Republic of Turkey continues provocative and unlawful actions in the eastern Mediterranean towards the republic of Cyprus." The claim was based on what Cyprus called an illegal seismic survey conducted Dec. 12, 2013-Jan. 14, 2014, by the vessel Barbaros Hayreddin Pasha, operated by Turkish state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corp. (TPAO).9

As a European Union (EU) member state, Cyprus has the support of the EU Commission, which reiterates that Turkey needs to commit itself unequivocally to good relations and to the peaceful settlement of disputes in accordance with the UN Charter, having recourse, if necessary, to the International Court of Justice. The commission also urged Turkey to avoid any kind of threat or action directed against a member state that could damage relations and the peaceful settlement of disputes.

The commission also re-emphasized the sovereign rights of EU member states that include entering into bilateral agreements and exploring natural resources in accordance with the EU and international law, including UNCLOS. The UN agreed with the appropriateness of this message.7

Turkey, however, despite making no formal claim regarding the maritime areas subject to the Israel-Cyprus EEZ delimitation agreement, included it as part of its ongoing Cypriot sovereignty issue. By ignoring Turkish Cypriots' rights, Turkey believes, Greek Cypriots' efforts for concluding such agreements raise questions as to their sincerity regarding the settlement process.

The Turkish ministry of foreign affairs said "Turkish Cypriots also have rights and jurisdiction over the maritime areas of Cyprus Island. The Greek Cypriot Administration does not represent in law or in fact the Turkish Cypriots and Cyprus as a whole. Therefore, agreements signed by the Greek Cypriots with countries of the region are null and void for Turkey."10

A Feb. 11, 2014, joint declaration by leaders of the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, Nicos Anastasiades and Dervis Eroglu, called the status quo unacceptable, higlighting the impact of new natural gas discoveries.

The Turkish scientific ship Barbaros Hayreddin Pasa, however, accompanied by two support vessels, carried out an additional seismic survey Oct. 20-Dec. 30, 2014, in Blocks 1, 2, 3, 8, and 9 of the EEZ of the Republic of Cyprus. The Barbaros on Oct. 21 came within 33 nautical miles of Cyprus's south coast and 29 nautical miles of the Saipem 10000, drilling Block 9 for Eni-Kogas.9

Turkey issued a navigational directive designating certain areas of Cyprus's EEZ as reserved.

Republic of Cyprus Minister of Energy, Commerce, Industry and Tourism Yiorgos Lakkotrypis responded that Eni-Kogas was continuing its drilling work on schedule in Block 9.

Turkey's action prompted Cyprus Pres. Nicos Anastasiades to pull out of reunification talks.11

Israel-Turkey

As the major holder of hydrocarbon resources in the eastern Mediterranean, Israel has a mutual interest in cooperating with Turkey, the region's largest consumer.

This relationship was strained in May 2010, when a Turkish organization, Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), attempted to break the Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip using the MV Mavi Mamara. The US State Department has officially expressed its concerns about the organization's ties with the Hamas terrorist group. The cruise ship was raided by the Israeli military. The raid resulted in the death of nine activists; eight Turkish nationals and one Turkish American.

Despite the Mavi Mamara crisis, Turkey has stated publicly that it sees Israel, along with Iraq, as viable sources of gas in its strategic plan to develop new supply routes.12

Turkey intends not only to obtain gas to meet its own demand from Israel but also to draw revenues as a transit hub for gas travelling via the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to Europe.

In April 2014, Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu (now prime minister) said, "The gap between the expectations of the two sides is closing" and that there was "positive momentum." He stressed that Turkey is interested in ending the crisis. "Progress has been made to a great extent, but the two sides need to meet again for a final agreement."13

Then-Turkish Prime Minister Racep Tayyip Erdogan (now president) next said the two countries had reached an understanding on the compensation amount Israel would pay the families of the victims of the 2010 Mavi Marmara raid and that once Turkey was allowed to send humanitarian aid to Palestinians in Gaza, relations could be normalized."13

Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman also said that relations between Israel and Turkey would soon be normalized.13

This progress was undone by the Israeli army's July 2014 ground operation into Gaza. Prime Minister Erdogan said that relations between the two countries would not improve while he remained in post.14

On Aug. 4, 2014, Turkish Energy Minister Taner Yildiz said that a natural gas project with Israel amid the ongoing violence in the Gaza Strip was out of the question. In the short term, the country has shut the door to an energy alliance with Israel, but the Turkish energy minister has said a partnership "could be discussed after everything has stabilized and calmed down."15

Both Jerusalem and Ankara have an incentive to overcome obstacles to bilateral cooperation.

Roles for US, EU

The Levant basin's complicated regional political, technical, and financial considerations lend themselves to potential mediation by an external party such as the US or EU.

United States

On Dec. 5, 2012, during the fourth US-EU Energy Council meeting, chaired by EU Vice-Pres. Catherin Ashton, Commissioner for Energy Gunther Ottinger, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and Deputy Secretary of Energy Daniel Poneman, the EU and the US formally linked eastern Mediterranean gas discoveries and energy security.

Under the title of "Energy Security," the council noted that "the significant current and future eastern Mediterranean gas discoveries could enhance the energy security of countries in the region. The US and EU are ready to assist interested countries in using their energy resources to best serve their national and regional economic interests."16

The US is suited for the role of regional mediator as an ally to most of the parties, a position which also allows it to address its three principal interests in the region:

• Upholding its allies' economic and physical security.

• Keeping the area integrated with global markets.

• Ensuring the safety of US citizens and energy employees.

Recognizing the advantage of a strategic approach to region-wide hydrocarbon development and coupling it with the interest from the US, Israel's Ministry of Energy and Water Resources submitted a letter to the US Department of Energy urging the US to assist in recruiting a major oil firm that could provide a strategic perspective on a basin-wide development plan.

The Interministerial Committee to Examine the Government's Policy Regarding Natural Gas in Israel concluded that the effective and complete development of the natural gas industry and export infrastructures in particular would be more likely executed if a major international operating company was present in Israel, one with knowledge and experience in developing natural gas.

To promote the entry of such entities to Israel's natural gas market, the director general of the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources was authorized to act in coordination with other relevant entities in the Israeli government.

A partial outcome of that recommendation was Australia-based Woodside Petroleum's ultimately unsuccessful attempt to acquire 25% of Leviathan field.

With the chance of incorporating a major oil firm to advance development removed, the burden of generating the level of cooperation needed for a full development of the Levant Basin returned to the states of the eastern Mediterranean.

European Union

With concerns in the EU regarding the future supply of hydrocarbons and threats to its supply security, the EU cannot ignore the opportunity that has arisen in the eastern Mediterranean.

The EU depends heavily on imports, which account for 53% of its consumption at a cost of more than €1 billion/day. This includes 88% of its crude oil, 66% of its natural gas, 42% of its solid fuels such as coal, and 40% of its nuclear fuel. In 2013, 39% of EU gas imports by volume came from Russia, 33% from Norway, and 22% from North Africa (Algeria, Libya). In terms of its natural gas market, two-thirds of the EU's imported gas comes from countries outside of the European Economic Area.17

These figures show the EU to be vulnerable to external energy shocks. Many member states rely heavily on a single supplier. Six depend entirely on Russia for their natural gas. The Baltic states, Finland, Slovakia, and Bulgaria depend on a single supplier of gas imports. The Czech Republic and Austria also have very concentrated imported gas supplies.

Three member states-Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania-rely on a single external operator for the operation and balancing of their electricity network and for a large share of their electricity supply. The seriousness of these dependencies became clear during the winter gas shortages in 2006 and 2009 and more recently the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

A European Commission's Stress Test Communication analysis published Oct. 16, 2014, presented the results of a modeling exercise conducted by 38 European countries, including EU member states and neighboring countries. The test analyzed different scenarios, in particular a complete halt of Russian gas imports into the EU for a period of 6 months.

The tests showed that a prolonged supply disruption would substantially impact the EU. Particularly affected would be eastern EU countries and other nearby countries. If all countries cooperated with each other, however, protected consumers would remain supplied even in the event of a 6-month gas disruption.

The Stress Test Report was the first concrete action regarding short-term energy security measures, following adoption by the European Commission of the European Energy Security Strategy on May 28, 2014. The report recommended completing the internal energy market, increasing energy efficiency, diversifying external supply sources, and exploiting indigenous sources (hydrocarbon and renewable).18

An internal EU report from July 2014 showed that development of markets and gas infrastructure (interconnectors, reverse flows, and storage) was improving supply resilience, but a short-term winter supply disruption through Ukraine transit routes would still threaten, especially, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Greece.

The flexibility of transport infrastructure in terms of location, number, and available capacity of pipelines and LNG terminals, underground storage, and how infrastructure is operated plays an important role in shaping the efficiency of the region's gas sector. The potential to operate pipelines in two directions increases supply resilience in case of a disruption.17

Current projections see Europe's dependence on imports increasing in the future, and the EU has no alternative but to increase LNG supplies and try to diversify suppliers and routes to include nearby, reliable sources. Possibilities include Caspian basin sources via further expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor, as well as Middle Eastern, and North African gas (with careful consideration of long-term stability issues), or eastern Mediterranean gas.

The Mediterranean approach is consistent with the EU policy of enhancing its partnership with the countries in the region, especially the energy partnership, following the Euro-Mediterranean Policy and the Barcelona Declaration from 1995. Eastern Mediterranean countries with potential gas resources enjoy close relations with the member states of the EU molded by geographic proximity and historical ties. And, as stated, Republic of Cyprus is also an EU member state.

Close cooperation between the EU and the countries in the region will play a key role in developing its gas. The choice of routes, the means of transportation, and the selling price will determine the viability of EU gas imports from the eastern Mediterranean. In addition to the options under assessment, such as an LNG terminal in Cyprus and a pipeline from offshore Cyprus to Greece via Crete, all potential routes should be considered and assessed from an energy security point of view.

In July 2013 the EU opened an energy dialogue with Israel to promote cooperation on issues related to access, pricing, and infrastructure for Israel's gas market. The meeting also discussed cooperation in research, promotion of renewable energy development, deployment of smart grids, and demand response management. The EU's increasing dependence on gas imports has increased the risks to security of supply. A reliable, transparent, and interconnected market has the potential to mitigate these risks.

To avoid missing the opportunity of developing Levant basin's gas resources to their full potential, the EU (and the US) must adopt proactive policies and accelerate dialogues with the relevant parties toward a new formal mechanism of coordination and cooperation.

The subjects on an East Mediterranean EU-US initial regional hydrocarbon agenda should include environmental, geological and geophysical, and other science and safety-related issues. With that approach, the EU would be able to share its knowledge and capabilities with the eastern Mediterranean neighboring states, and in return, gain improved security of supply.

Future development

The window of opportunity is closing for successful development of Levant basin resources. The responsibility for steering the relevant powers to that aim relies on regional governments, the US, and the EU.

The EU and the US could contribute to the regional process by bringing the relevant parties under the umbrella of the US-EU Energy Council or similar framework. The process would also benefit from the participation of professional and commercial regional partnerships, including public and private sector experts from the US, the EU, and regional parties.

References

1. Natural Gas Europe, "Cyprus Gas in the Spotlight," Apr. 22, 2014.

2. The Aspen Institute, "US Mediating Lebanon's Maritime Border Dispute," Dec. 6, 2012.

3. "US proposal for Lebanon Israel maritime boundary," Menas Borders, Dec. 6, 2013.

4. Wahlisch, M., "Israel-Lebanon Offshore Oil & Gas Dispute-Rules of International Maritime Law," American Society of International Law, Vol. 15, No. 31, Dec. 5, 2011.

5. Mansour, A., Minister for Foreign Affairs & Emigrants, Republic of Lebanon, Open Letter to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, UN Doc. 3372.11D (translated from Arabic), Sept. 3, 2011.

6. Nash, M., "Points of Contention," NOW Lebanon, July 13, 2011.

7. Azulai, Y., "Israel Navy has good answer to Hezbollah threats," Globes Online, Jan. 19, 2015.

8. Bizzotto, M., Question posed on EU parliamentary website, Aug. 7, 2013. Responded to by Mr. Fule on behalf of EU Commission, Sept. 17, 2013, www.europarl.europa.eu.

9. Emiliou, N., "Letter dated 13 February 2014 from the Permanent Representative of Cyprus to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General," Agenda Item 76, UN General Assembly, 68th Session, Doc. A/68/759, Feb. 18, 2014.

10. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey, "No: 288, Regarding the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Delimitation Agreement Signed Between Greek Cypriot Administration and Israel," Dec. 21, 2010.

11. Psyllides, G., "Total unlikely to stay," Cyprus Mail, Jan. 22, 2015.

12. Matalucci, S., "An Interview with Hasan Mercan, Turkish Deputy Minister of Energy," Natural Gas Europe, Apr. 28, 2014.

13. Ravid, B., "Lieberman: Israel-Turkey relations will soon normalize," HAARETZ, May 3, 2014.

14. "Turkey, US in row over Erdogan's remarks on Israel," Hurriyet Daily News, July 24, 2014.

15. "Turkey rules out energy alliance with Israel until Gaza peace: Minister," Hurriyet Daily News, Aug. 4, 2014.

16. "Joint statement on the U.S. - EU Energy Council," US Department of State, Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, Washington DC, Dec. 5, 2012.

17. "Imports and Secure Supply," European Commission, European energy security strategy meeting, Brussels, July 2, 2014.

18. "Gas stress test: Cooperation is key to cope with supply interruption," European Commission, Oct. 16, 2014.