East Mediterranean Development-1: Levant basin presents narrowing resource opportunities

Shaul Zemach

Independent consultant

Tel-Aviv

Discovery of the Levant basin province in the easternmost Mediterranean has provided an opportunity to modifify traditional political structures in the region. Renewed interest in recoverable resources has enhanced existing alliances, provided incentive for collaboration between political adversaries, and caused the emergence of new sources of conflict.

The first part of this Levant basin series focuses on specific regions, their resource potential, their associated challenges, and the most recent status on development.

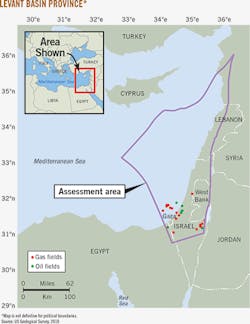

The US Geological Survey (USGS) assessed the province for the first time in 2010 and estimated mean undiscovered, technically recoverable reserves at 122 tcf of natural gas and 1.7 billion bbl of oil and natural gas liquids (OGJ Online, Apr. 8, 2010).

The Levant basin province encompasses 83,000 sq km of the eastern Mediterranean, which is bounded in the east by the Levant transform zone, in the north by the Tartus fault, in the northwest by the Eratosthenes Seamount, in the west and southwest by the Nile Delta Cone Province boundary, and in the south by the limit of compressional structures in the Sinai. In geopolitical terms, the Levant basin province extends from Egypt in the south to Turkey in the north. The basin also is exposed in Israel, Cyprus, Lebanon, and Syria (Fig. 1).

Due to this wide-ranging geographical expanse, many believe the discovery of Levant basin could transform the dynamics in the eastern Mediterranean region, with new political and economic consequences playing out among the various countries within its boundaries.

Geopolitical puzzle

To exploit fully the region's resource potential, new hydrocarbon discoveries in the Levant basin will inevitably require some form of collaboration between neighboring countries in the East Mediterranean. The "Levant basin puzzle" is defined by the interdependence of these states. Without mutual assistance, these countries may find it difficult fully to develop resources within their respective borders or exclusive economic zones.

The USGS's distributed mean of 1.7 billion bbl of undiscovered oil in the Levant basin is within a range of 483-3,759 million bbl. For undiscovered gas, the total mean volume 122 tcf, is within a range of 50-227 tcf. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that USGS estimates of an additional 1.7 billion bbl of oil, if realized, would meet regional demand for roughly 20 years at current levels of consumption, while 122 tcf of natural gas could meet current demand almost indefinitely.1

These basin-wide estimates assume full development of technically recoverable resources; however, geopolitics in the region have eliminated single-unit development. Cooperation is needed to improve field development and operational efficiency. The current status of Levant basin exploration is a narrowing opportunity for its neighboring states, their allies, and their economies.

Country assessments

Potential and proved resources are not equally distributed in the East Mediterranean. Israel's Ministry of Energy estimates volumes of natural gas within the Israeli exclusive economic zone (EEZ) to be 50 tcf.

In a Dec. 19, 2013, interview with Natural Gas Europe, former Lebanese Minister of Energy & Water Gebran Bassil said the country's offshore province could contain up to 96 tcf of natural gas, with 850 million bbl of oil onshore.2

In its analysis of Lebanon, the EIA said that Lebanon's government estimates potential natural gas reserves of 25 tcf or more in its offshore territory. This figure remains speculative until further exploration provides additional data.3

Cypriot officials have estimated that the 13 blocks in the country's EEZ could hold as much as 60 tcf. Other less optimistic estimates hold a 40 tcf reserves basis for the six blocks tendered, including Aphrodite (OGJ Online, Apr. 7, 2014).4

Turkey's recoverable natural gas reserves were close to 211 bcf in 2009, with domestic gas production of about 35.3 bcf/year.5 As of Jan. 1, 2014, Tukey's natural gas reserves rose to 241 bcf (OGJ Online, Jan. 6, 2014). Turkey produced 22 bcf of natural gas in 2012, and the country relied almost exclusively on imports to meet domestic demand.

Despite efforts by state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corp. (TPAO) to intensify gas exploration, Turkey is not expected to take an active supply role in the East Mediterranean. Being a dominant power in the region, however, Turkey's influence will impact future natural-gas-related development in the Levant basin.

The basin's two remaining littoral states, Egypt and Syria, have been too consumed by domestic unrest to generate a coherent response to offshore gas discoveries.6 Yet it would be reasonable to assume that interested parties within those states are planning for future post-crisis arrangements.

In December 2013, Syria signed an agreement with Russian oil and gas company SoyuzNefteGaz Ltd. to prospect jointly for oil off Syria's Mediterranean coast. According to Syrian, Russian, and Iranian state news agencies, the contract is for oil exploration and production in Block 2 of Syria's territorial waters, which stretch from the shore of the coastal city of Tartous to the city of Banyas and covers 2,190 sq km.

SoyuzNefteGaz will reportedly finance the $90 million project in Syria. If test drilling confirms commercial scale reserves of oil and gas, SoyuzNefteGaz will build the necessary infrastructure for development and extraction.

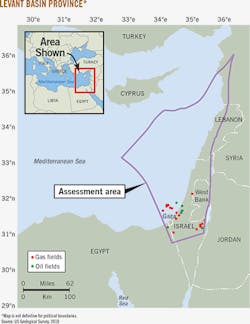

Regional estimates do not adhere to those of the USGS for the Levant basin (Table 1). It is important to note, each of the region's countries' estimates of available resources in their respective EEZs accounts for supply-side parameters as well as future domestic demand, technical export options, target export markets, and pricing.

The character of the relatively small domestic gas markets and the numerous geopolitical, commercial, and regulatory hurdles facing available export options converge as challenges to develop fully East Mediterranean discoveries. This combination also reveals diverging priorities among the region's neighboring states. Potential export markets entail decision making that will include the combination of destinations, technologies, and infrastructure.

Israel

With more than 31 tcf of estimated natural gas and a stable flow of domestic supply, the state of Israel plays a leading role in future developments of the Levant basin.

Israel has two large offshore hydrocarbon structures. Tamar field, discovered at the end of 2009 and holding an estimated 10.59 tcf in place, began producing commercially in March 2013. The second, Leviathan field, was discovered at the end of 2010. Assessments of the Leviathan field indicate there could be as much as 22 tcf of recoverable natural gas in place (OGJ Online, Sept. 4, 2014). Exploration over the past several years uncovered additional, smaller fields.

Partners in Tamar field include Noble Energy Inc. (36%), Isramco Ltd. (28.75%), Delek Group Ltd. units Delek Drilling LP and Avner Oil and Gas LP (15.625% each), and Alon Natural Gas Exploration Ltd. (4%).

Partners for Leviathan field include Noble Energy Inc. (39.66%), Delek Drilling LP and Avner Oil and Gas LP (22.67% each), and Ratio Oil Exploration (1992) LP (15%).

Recently, the Israeli Anti-Trust Commissioner announced interest in taking regulatory action against Noble Energy and Delek group due to their perceived dominance of Israel's energy market. After an initial period of uncertainty, the government of Israel has approved its natural gas export policy. The plan gives the priority to domestic supplies of natural gas and imposes limitations on petroleum rights holders' market flexibility while providing some natural gas for export.7 Stakeholders are examining potential export destinations.

Primary technological approaches include LNG (floating or land-based) and large-scale, regional offshore pipelines. Some consideration has been given to an onshore LNG plant in Israel; however, the government continues to question the viability of this option. Floating LNG (FLNG) and compressed natural gas (CNG) transport are also under consideration for Israeli exports to small, nearby markets, but the commercial viability of CNG technology for this region is uncertain.

Levant basin development may be assisted through large-scale pipelines to Turkey, Greece (via Cyprus), and possibly to Egypt's existing, under-utilized facilities. In some cases, these two approaches could be merged.

In the case of an offshore pipeline to Egypt, the flow of Israeli gas would offset Egypt's former export volumes to Europe that were redirected for domestic supply. This alternative would use unused liquefaction trains in Egypt. Negotiations with BG Group and Union Fenosa Gas SA are ongoing.

Partners for Israel's Tamar field have signed a letter of intent with Union Fenosa to export 159 bcf of gas over 15 years to the Damietta LNG plants in Egypt. Leviathan field partners have agreed to supply BG Egypt with 247.2 bcf/year of natural gas over 15 years at its Idku LNG plants.

Smaller volumes of exports are planned for Jordan-based customers Arab Potash Co. and Jordan Bromine Co. Under terms of the agreement, Noble Energy's subsidiary will supply 63.6 bcf of natural gas from the Tamar field off Israel to both companies for use in their plants near the Dead Sea. Natural gas sales will start in 2016 following completion of minimal pipeline installations.

The Leviathan partners also signed an agreement with Palestine Power Generation Co. PLC (PPGC). Plans call for construction of a power plant at the north end of the West Bank to supply electricity to the Palestinian authority. Leviathan's operators will supply PPCG with as much as 167.7 bcf (total) of natural gas for up to 20 years.

On Sept. 3, 2014, Noble Energy Mediterranean Ltd. signed a letter of intent with the Jordanian National Electric Power Co. Ltd. to negotiate a 15-year gas supply contract from Leviathan for up to 1,589 bcf.

Cyprus

Appraisals of Noble Energy's Aphrodite discovery in Cyprus in late 2011 in deepwater Block 12 indicate gross mean reserves of 5 tcf, with a range of 3.6-6.0 tcf. Cyprus's domestic market will consume some of this gas, particularly for power generation for which it will replace expensive fuel oil and gas oil, but the bulk will need to be sold in international markets to justify the expense of developing the field and building a gas pipeline to shore.

Block 12 was awarded to Noble Energy during the first licensing round in 2007. Blocks 2, 3, and 9 were awarded to partners Eni SPA and Korea Gas Corp. (KOGAS), and Blocks 10 and 11 were awarded to Total SA in the second round. All blocks were awarded as production sharing contracts.

Cyprus intends to export natural gas from the Aphrodite field by 2020, with a planned LNG plant near Vasilikos on Cyprus's southern coast about 25 km east of Limassol. Noble Energy and its partner in Block 12, Israel's Delek Group, signed an agreement with the Cyprus government in June 2012 to develop the Vasilikos liquefaction plant. Its first phase includes three 5-million tonne/year (tpy) liquefaction trains to be fed by natural gas from Israel's Leviathan field. Cypriot Natural Gas Public Co. (DEFA) estimates the plant will cost $10 billion.8

On Dec. 19, 2014, Cyprus's Energy Ministry reported that the Onasagoras prospect in Block 9 was drilled to 19,000 ft (Eni-KOGAS consortium) and failed to find commercial quantities of natural gas.

Eni is moving 55 km to its next Block 9 target, Amathusa field, where preliminary data suggest the geological probability for natural gas is lower than for Onasagoras.

Total recently completed geological surveys of Blocks 10 and 11 without finding any potential drilling targets. According to Cyprus media, the Ministry of Energy defined the possibility of coming to an arrangement with French operator Total as "remote."9

In September 2012, DEFA announced interest in finding an intermediate solution for the supply of natural gas to its Vasilikos power station. A delegation from Cyprus, led by Minister of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism Yiorgos Lakkotrypis, who is in charge of energy affairs, visited Israel to discuss the possibility of a bilateral agreement on natural gas supply. Both Israel and Cyprus expressed their willingness to find a solution. Discussion centered on economies of scale, joint development of export facilities, and finding an interim solution for Cyprus's demand.

DEFA continued to seek a commercial agreement for the urgent supply of 3-5 years of natural gas. The power company's supply options included CNG and LNG via floating storage and regasification.

DEFA announced in 2014 an invitation for an open competition to supply natural gas to Vasilikos for up to 10 years commencing Jan. 1, 2016. Interested parties submitted proposals substantially to reduce electric generation costs through yearend 2018, providing a complete solution covering all commercial and infrastructure needs, including sourcing, transportation-shipping, and processing.

Cyprus's strategic plan is to become the East Mediterranean hub for hydrocarbon resources by incorporating domestic gas from Aphrodite with resources produced off Israel as feedstock for the Vasilikos liquefaction plant.10

The country's Aphrodite field contains an estimated 141 bcf of gas, which includes additional sites within the Aphrodite license. It is currently facing difficulties due to an imbalance with Israeli gas quantities. Israel is also determined to keep exports under its own control.

As a consequence, Cypriot officials and Noble Energy have made export lines to Egypt a priority, with FLNG and CNG under consideration as close alternatives.

Cyprus took further steps Nov. 28, 2014, when it signed a joint declaration with Egypt and the Hellenic Republic. Ministers from these three governments established a framework for tripartite talks on cooperation in hydrocarbon resource development. The trilateral partnership is examining ways and means for the optimal development of regional resources.11

Turkey

EIA has estimated that Turkey's energy consumption will double in the next decade. In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast Turkey will likely see the fastest medium to long-term growth in energy demand among its member countries.

Turkey holds a strategic role in natural gas transit because of its geographical placement between continental Europe, the world's second-largest gas market, and the vast natural gas reserves of the Caspian basin and the Middle East.

The share of natural gas in Turkey's total primary energy supply increased to 32% in 2012. Turkey's gas demand increased to 1,599.8 bcf in 2012, up from 24.7 bcf in 1987. Indigenous natural gas production totaled 22.3 bcf in 2012. The transportation sector was the largest consumer of natural gas in 2011 at about 48% of the country's total gas consumption.12

Turkey's energy demand growth was among the fastest in the world in 2010 and 2011, although slower economic growth in 2012 dampened natural gas consumption growth to some extent. According to the Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (ETKB), between 1990 and 2008 the country's average rate of increase in primary energy demand was 4.3%/year. Among other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, Turkey has had the highest rate of energy demand increase of the past 10 years. Projections by the Ministry show this trend will continue in the medium run.

In 2008, total primary energy consumption was 106.3 million petroleum ton equivalent (TEP), while production was at 29.2 million TEP. Of total energy supply, natural gas was largest (32%), followed by petroleum (29.9%), coal (29.5%), and renewable energy sources including hydraulic (8.6%). The baseline scenario has primary energy consumption increasing 4%/year by 2020. Forecasts for Turkey's natural gas demand by 2030 are 2,698-2,959.4 bcf.13

Secure energy supply remains essential to the Turkish economy. Recent progress includes restructuring the Turkish energy market toward more transparent competition, identifying and using domestic and renewable resource potentials, making nuclear energy a part of electricity production, and pursuing energy efficiency and new energy technologies.

ETKB established Turkey's energy policy with the principal aims of:

• Making energy available for consumers in terms of cost, time, and abundance.

• Exploiting public and private facilities within the framework of free market practices.

• Discouraging import dependency.

• Securing a strong position for Turkey in regional and global trade of energy.

• Ensuring the availability of diversified resources, routes, and technologies.

• Ensuring maximum use of renewable resources.

• Increasing energy efficiency.

Russia was the largest supplier to Turkey, representing 58% of total imports in 2012. Turkey has four international gas pipelines in operation with a total import capacity of 1,645.6 bcf and plans to diversify natural gas imports further with new major cross-border pipelines and LNG terminals.14

Turkey receives imports from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran. Through the TANAP project, the country is set to increase its Azeri intake via a pipeline from Azerbaijan in addition to the South Caucasus pipeline.15

Besides Turkey's being a rapidly growing consumer, its role as an energy transit hub is increasingly important. Turkey is a key part of oil and natural gas supplies movement from Russia, the Caspian region, and the Middle East to Europe. Although the Turkish government formally supports developing the country as a natural gas export hub, Turkey is extremely vulnerable to supply disruptions and may have insufficient pipeline capacity to keep pace with both greater exports and increasing domestic demand.16

Key elements of Turkey's overall gas security policy are to diversify its long-term supply portfolio and to form an energy hub from Central Asia and the Middle East to Europe.14

With a view toward meeting its increasing demand, making sufficient energy-sector investments, and increasing economic efficiency, Turkey launched an initiative after 2000 to increase competition in the energy sector. Within this context, the following legislation was passed:

• Electricity Market Law (2001).

• Natural Gas Market Law (2001).

• Petroleum Market Law (2003).

• LPG Market Law (2005).

• Law on Utilization of Renewable Energy Resources for the Purpose of Generating Electrical Energy (2005).

• Energy Efficiency Law (2007).

• Law on Geothermal Resources and Mineral Waters (2007).

• Law on Construction and Operation of Nuclear Power Plants and Energy Sale (2007). This law also introduced regulations regarding use of domestic coal resources for the purpose of generating electrical energy, encouraging the establishment of domestic coal-fired thermal power plants.

• Law on the Amendment of Electricity Market Law No. 5784 on Supply Security (2008). In its long-term planning work, the Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources expects to achieve the following targets by 2023:

• Make complete use of potential indigenous coal and hydraulic resources.

• Maximize use of renewable resources.

• Incorporate nuclear energy into electricity generation by 2020.

• Secure rapid and continuous improvement in energy efficiency in a way that parallels EU countries.

The Ministry of Energy's working plan consists of three pillars (natural gas, coal, and hydraulic), with renewable resources and nuclear energy also included. Turkey further continues to attach importance to development of its domestic hydrocarbons.

For meeting the increasing European demand for natural gas, Turkey attaches strategic importance to ensuring that projects for transferring resources to Europe pass through the Turkish territorial control zones. This preserves the policy of making Turkey a natural gas trade hub in the medium and long term. In its Strategic Plan 2010-14, the Turkish administration emphasized the need to increase energy supply security by diversifying the country's resources, routes, and technologies.15 17

Lebanon

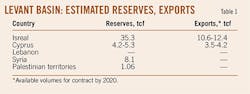

In May 2013, the Lebanese Ministry of Energy and Water launched the first licensing round for offshore oil and gas exploration, opening up bidding for 5 out of 10 offshore blocks. Per the requirements set forth by Lebanon's Peteroleum Administration (PA), interested companies were prequalified, with submissions from 52 operators from 25 countries.

Out of these applicants, 12 were prequalified as rightsholder operators and 34 as rights-holder nonoperators (Table 2). Per Lebanon's Offshore Petroleum Resources Law, companies must form consortia of at least three with one acting as operator. Lebanon's first offshore licensing round was announced with a submission deadline of Apr. 10, 2014, extended to Aug. 14, 2014. The Lebanese cabinet, however, has delayed issuing decrees delineating offshore blocks and has also stalled in providing a model exploration and production agreement.

On Aug. 8, 2014, the Lebanese Minister of Energy and Water announced that the deadline for bid submission was suspended indefinitely to a maximum period of 6 months from the date of the adoption of the two decrees related to block delineation and tender protocol.18

Five of 10 offshore blocks are open for bidding (Blocks 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9). Additional blocks may be opened after Lebanon's government ratifies the necessary decrees.

Future success

As demonstrated by activity within the last 5 years, the Levant basin presents ample opportunities for many countries with access to its resources. While many of these countries are preparing to explore Levant basin's potential, problems surround successful development of the area.

The follow up to this first installment will discuss probable outcomes and potential solutions.

References

1. US Energy Information Administration, "Overview of oil and natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean region," updated Aug. 15, 2013.

2. Ayat, K., "Lebanon: Interview With Lebanese Caretaker Ministry of Energy & Water Gebran Bassil," Natural Gas Europe, Dec. 9, 2013.

3. US Energy Information Administration, "Country Analysis Note, Lebanon," updated March 2014.

4. Tsakiris, T., "The Hydrocarbon Potential of the Republic of Cyprus and Nicosia's Export Options," Journal of Energy Security, Aug. 22, 2013.

5. International Energy Agency, "Energy Policies of IEA Countries - Turkey, 2009 Review," 2010.

6. Zhukov, Y.M., "Trouble in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea-The Coming Dash for Gas," Foreign Affairs, Mar. 20, 2013.

7. "The Recommendation of The Inter-ministerial Committee to Examine the Government's Policy Regarding Natural Gas in Israel," Executive Summary, September 2012.

8. Ioannou, C., Cyprus Natural Gas Public Co. (DEFA), "Cyprus: Exploring the Evaluation of the East Mediterranean new energy hub", East Med and North Africa Gas Forum, Rome, Feb. 26-28, 2013.

9. Psyllides, G., "Total unlikely to stay," Cyprus Daily, Jan. 22, 2015, www.cyprus-mail.com.

10. Lakkotrypis, Y., Address by the Cypriot Minister of Energy, Commerce, Industry, and Tourism, Presented at the 7th International Conference for Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Regional Development, May 6, 2014.

11. Joint Declaration from Minister of Energy, Cyprus, Minister of Petroleum of the Arab Republic of Egypt, and Minister of Environment of the Hellenic Republic, Nov. 11, 2014.

12. "Energy Supply Security 2014," International Energy Agency, p. 451.

13. Melikoglu, M., "Vision 2023: Forecasting Turkey's natural gas demand between 2013 and 2030," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 22, June 2013, pp. 393-400.

14. "Oil and Gas Emergency Policy-Turkey 2013 update," International Energy Agency, pp. 19, www.iea.org.

15. Matalucci. S., "An Interview with Hasan Mercan, Turkish Deputy Minister of Energy," Natural Gas Europe, Apr. 28, 2014.

16. "Countries Analysis, Turkey," US Energy Information Agency, updated Apr. 17, 2014, www.eia.gov.

17. "Strategic plan 2010-14," Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Turkey, www.enerji.gov.tr

18. Ministry of Energy and Water, Petroleum Administration, Lebanon, www.lpa.gov.lb

The author

Shaul Zemach ([email protected]) is the former director-general of the Israeli Ministry of National Infrastructure, Energy, and Water Resources. He also served as the chairman of the (T)Zemach Committee, assigned by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with the task of examining government policies regarding natural gas in Israel. He holds a bachelors in economics and international relations from the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, and a masters in public policy from Tel Aviv University.