Turkmenistan positions itself as Eurasian natural gas power

Qaya Mammadov

Baku, Azerbaijan

Natural gas's share of global energy demand is set to increase from 21% in 2011 to 25% by 2035. But most proven gas reserves are concentrated in a few countries far from the main consuming markets. Even when pipeline transportation might be geographically possible, there are often economic and political interests working against it.

Turkmenistan is an example of how geopolitical considerations and narrowly defined interests can prevent huge natural gas potential from being realized. Difficulties in using Russia's pipeline network for exporting gas produced in Turkmenistan precipitated a dramatic decline in production, to 12 billion cu m (bcm) in 1998 from 81.1 bcm in 1989, recovering only after exports began to Iran and later China.

This article will examine Turkmenistan as a key natural gas holder in the center of Eurasia, an area which has so far been prevented from realizing its huge potential due to geopolitical considerations and unhealthy economic practices.

Background

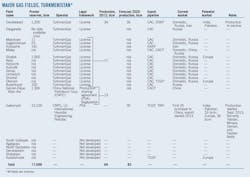

Turkmenistan has 17.5 trillion cu m (tcm) of proven natural gas reserves, 9.3% of global proven reserves and fourth largest after Iran, Russia, and Qatar. Gas reserves in Turkmenistan are concentrated in giant fields. Galkynysh field, close to the Afghan border in the country's southeast, has proven reserves of 13.1 tcm, 74% of total proven gas reserves in Turkmenistan.

With 244,000 b/d of oil production and proven reserves of 600 million bbl in 2012, Turkmenistan's role in that market is rather modest. Most of Turkmenistan's proven gas resources are in the Amu-Darya basin. Most of its proven oil reserves are in the Caspian basin.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimates that the Amu-Darya basin, 90% of which is in Turkmen territory, has technically recoverable undiscovered reserves of 6.9 tcm natural gas and 9.3 billion bbl NGL. According to USGS estimates, the Caspian basin may have undiscovered technically recoverable reserves of 1.4 tcm natural gas and 682 million bbl NGL. Most of those resources-81% of gas and an unspecified portion of NGL-are in the Southern Caspian basin, corresponding with the national maritime boundaries of Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan in the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1).

Galkynysh field (formerly Osman-South Yolöten) is the world's second biggest gas field, after South Pars-North field in the Persian Gulf. Other important fields are Yashlar, 1.4 tcm (sometimes shown as part of Galkynysh); Dauletabad, 1.2 tcm; and Shatlyk, 1 tcm (see accompanying table).

Legal framework

According to Turkmen law, all hydrocarbon resources in their untouched form belong to the state. The State Agency for the Management and Use of Hydrocarbons under the President of Turkmenistan (the Agency) creates agreements with foreign companies and implements them on behalf the Turkmen Government.

The Petroleum Law (2008) allows foreign companies to enter into production sharing agreements, concession agreements on the terms of royalty and tax, joint activity agreements, and risk service contracts. The Turkmen government has concluded nine production sharing agreements (PSA) and an unspecified number of service contracts with foreign companies. Disputes regarding contract areas in the Caspian Sea have prevented implementation of some of these contracts. Bagtyyarlyk, a generic name for the PSA with China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), is the only onshore gas PSA. Between Bagtyyarlyk and Galkynysh service contracts, CNPC controls 82% (14.4 tcm) of Turkmenistan's proven gas reserves.

Gas production

Turkmenistan's national gas company, TurkmenGaz, is still the largest producer of gas in the country. In 2012 it produced 80% (51 bcm) of the country's total. The remaining 13 bcm was produced by CNPC within Bagtyyarlyk. The share of the gas produced by foreign companies, however, is likely to increase due to the growth of their output in absolute numbers and production decline at TurkmenGaz' maturing Dauletabad field.

Bagtyyarlyk's contract area includes two large fields, Saman-Tepe and Altyn Asyr, with total proven reserves of 1.3 tcm. CNPC will carry out full-scale exploration, development, and production of natural gas under Bagtyyarlik for 30 years. All output, with an average volume of 20 bcm/year, is for export to China.

The Turkmen government in 2009 concluded a $10-billion service contract for Galkynysh with a consortium headed by CNPC and including LG International, Hyundai Engineering, and Petrofac. Galkynysh production started Sept. 4, 2013. Turkmenistan will export 30 bcm/year to China for 30 years under agreements reached at the time. The two countries, however, have set a target of bringing annual gas deliveries up to 65 bcm/year, 30 bcm from Galkynysh and the rest from the Bagtyyarlyk PSA and Turkmengaz' own production.

Turkmenistan can openly market any additional Galkynysh volumes beyond the 30 bcm/year committed to China. The Turkmen government maintains that the field can produce as much as 100 bcm/year, enough to simultaneously feed projected pipelines to Europe (30 bcm/year), India-Pakistan (33 bcm/year), and China.

Export infrastructure

There are four major export pipelines in Turkmenistan. One more is being built and two are under consideration. Combined total design capacity of existing export pipelines is 153 bcm/year. Actual transmission, however, is much lower, due to political and technical problems.

Turkmenistan does not border directly with Europe, China, or India, and depends on transiting gas through other countries. The Turkmen government's preference is to route transportation through those countries with which it has no or the lowest possible degree of conflict.

Turkmenistan has been making slow, but steady progress in diversification away from Russia. With the Korpezhe-Kurt Kui (KKKP) pipeline to Iran, inaugurated in 1997, Turkmenistan became the first energy-producing former Soviet republic (FSR) to build an export pipeline, albeit modest in size-13.5 bcm/year, 200 km long-bypassing Russia. Inauguration of the 30-bcm/year Central-Asia China pipeline in 2009 marked another large step in Turkmenistan diversifying its energy markets.

Existing pipelines

The Soviet-built Central Asia Center Pipeline (CAC), is Turkmenistan's oldest, most expanded system of pipelines, with outlets connected to almost all key deposits. It has 90-bcm/year design capacity, but due to a lack of proper maintenance and limited Russian gas purchases, only 10% of its capacity is used.

The second Soviet-era pipeline taking Turkmen gas to Russia, the Bukhara-Urals Pipeline (BUP), also functions below its design capacity (20 bcm/year) due to poor maintenance and low demand. Both pipelines are connected to the Russian export pipeline network to Europe. Total volume of gas exported in 2012 via CAC and BUP was 9.9 bcm, less than 10% of their combined design capacity of 110 bcm/year.

There are also two operating pipelines through which Turkmen gas is exported to Iran: KKKP and the Dauletabad-Khangiran Pipeline (DTP), operational since 2010 with a design capacity of 12 bcm/year.

Both pipelines feed local consumption in northeast Iran. In 2012 total exports to Iran via KKKP and DTP were 9 bcm, 35% of their combined design capacity (25.5 bcm/year). This underutilization may be due to lower Iranian demand, not maintenance problems.

The latest major export pipeline system built in Turkmenistan is the Central-Asia China Pipeline system (CACP). It is designed to use four lines (A, B, C and D) starting in Turkmenistan and passing through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan before reaching China. A, B, and C are parallel pipelines. Line A and B became operational in 2009 and 2010 respectively. Line C followed in 2014 (OGJ Online, June 3, 2014). Line D will follow a different route-through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan-and become operational in 2018.

The different path for Line D is probably associated with a Chinese preference to avoid having all its lines run through Kazakhstan and, more importantly, to be able to import gas from Tajikistan, where CNPC is already negotiating exploration and production contracts. The four lines' combined capacity will be 80 bcm/year.

China is currently building a third West-East pipeline from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to Shanghai. Line I (17 bcm/year) ships domestic production Line II (30 bcm/year) is an extension of CACP Lines A and B. Line III's design capacity is also 30 bcm/year and it will serve as an extension of Line C inside China. CNPC expects Line III to be commissioned this year (OGJ Online, Jan. 17, 2013).

Future pipelines

Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) is a proposed 300-km, 30-bcm/year subsea pipeline with a total cost of up to $5 billion that would start on the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea and connect to existing and future export gas pipeline in Azerbaijan heading to Europe.

Construction of the TCGP is far from guaranteed, but the Turkmen government has taken some practical actions towards its realization. It started building the 766-km, 30-bcm/year East-West Pipeline in 2012. This pipeline starts in the country's southeast, where its largest gas fields are, and will run to the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea near the port of Türkmenbasy. From there, it will either continue to Baku, Azerbaijan, via the TCGP or to Russia, along the coast, in parallel with one of the existing CAC lines.

Kazakhstan has also expressed an interest in connecting to TCGP for exporting associated gas from the Tengiz field, which it uses now for reinjection or simply flares. Political problems have so far prevented construction of the TCGP.

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline (TAPI) would allow Turkmenistan to export 33 bcm/year gas to Pakistan and India. At an estimated cost of $7.6-10 billion it would start in the Dauletabad or Galkynysh field, both of which are close to the Afghan border, and run through Afghanistan to Multan, Pakistan, and Fazilika, India. Security problems in Afghanistan and India's unwillingness to depend on Pakistan for transit are the main obstacles to this project.

Key markets

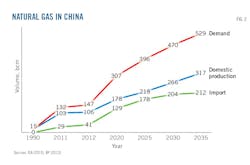

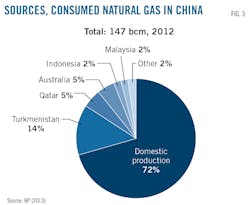

China is and will remain in the mid-term the most important export market for Turkmen gas. It is also a rapidly growing market. According to the IEA, China's demand for natural gas, 132 bcm/year in 2012, will increase 6% annually and reach 529 bcm/year by 2035. Its domestic production, 103 bcm in 2012, will not keep pace, averaging 4.8% growth/year to reach 317 bcm/year in 2035. China's consumption of imported gas will increase from 21% (41 bcm) of demand in 2012 to 40% (212 bcm) in 2035 (Figs. 2-3). Its need for Turkmen gas will increase accordingly.

China is committed under current contracts to buy at least 50 bcm/year from Turkmenistan by 2020. In 2012 Turkmenistan provided more than half (21 bcm) of China's 41 bcm/year gas imports. CNPC estimates Turkmenistan will provide at least 50% (65 bcm) of China's expected 129 bcm/year gas imports by 2020.

These volumes will still be well below the amount of gas (250 bcm/year) called for in the Turkmen government's mid-term export plans. Possible gas exports from Russia to China from the Siberian Kovykta field and prospective shale gas production in China also challenge Turkmenistan's role in its only viable big market.

China has the largest volume (31.5 tcm) of technically recoverable shale gas reserves in the world, giving it additional leverage in dealing with Turkmenistan and prompting continued Turkmen efforts to diversify export markets.

India, Pakistan

Energy demand is growing in both India and Pakistan, which have proven natural gas reserves of 1.3 tcm and 0.7 tcm, respectively. The IEA predicts demand for natural gas in India will increase to 172 bcm/year in 2035 from 61 bcm/year in 2011, an annual increase of 4.4% on average. The increase in its domestic production (46 bcm in 2011) will be 3.3%/year and will reach only 98 bcm/year in 2035. The share of imported gas in domestic consumption will accordingly increase to 43% (74 bcm) in 2035 from 25% (15 bcm/year) in 2011.

In the absence of an import pipeline and with only one LNG terminal (OGJ Online, July 22, 2015), Pakistan's economy relies heavily on domestic gas production. Production peaked in 2012 at 41 bcm and is expected to grow, but not enough to meet demand. The Pakistani government says the country already needs an additional 20 bcm/year of gas imports and expects the need for imports to rise to 40 bcm/year by 2023.

India and Pakistan for nearly 20 years have been considering building a pipeline to import as much as 33 bcm/year from Turkmenistan. Because neither country shares a common border with Turkmenistan, however, the pipeline must be built either through Afghanistan or Iran.

The Iranian option is problematic for two reasons. With its vast gas reserves and export plans, Iran is a competitor to Turkmenistan. Iran seeks to export its gas to India and Pakistan through an envisaged 40-bcm/year Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline. Turkmenistan might be concerned that Iran would be tempted to take advantage of its transit position to control Turkmen export volumes for the benefit of its own gas exports. US sanctions on Iran, which are still in place, also discourage companies from investing in such projects.

The US government supports TAPI, which bypasses Russia and Iran and targets a market other than China, apparently as a means of decreasing all three countries' influence in Central Asia. The main obstacle to this route is the unstable security situation in Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan, where uncontrolled armed groups have regularly sabotaged gas pipelines.

TurkmenGaz earlier this year at a meeting in Ashgabat agreed to lead the consortium planning to build, own, and operate TAPI, ending the search for international company to play that role (OGJ Online, Aug. 6, 2015). The countries, however, have yet to reach a final investment decision and, apart from commercial and security problems with regard to instability in Afghanistan, India seems unenthusiastic about making its energy supply dependent on transit through Pakistan. India's continued reliance on domestic coal, as well as large scale-investments in expanding LNG import capacity and nuclear power, highlight its skepticism on the prospect of gas imports via Pakistan.

Turkmenistan, however, seems determined to take practical action toward completing the project. On Nov. 7 the Turkmen Government ordered state-owned companies Turkmengaz and Turkmennebitgazgurlushyk to start building the 200 km section of TAPI running through Turkmenistan. A groundbreaking ceremony is planned for Dec. 13.

Western markets

For purposes of this article Western markets include Turkey, Europe, and European FSR which are net gas importers: Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova. Although the market situation in each is unique, they share one important feature; any imports of Turkmen gas there would compete directly with Russia.

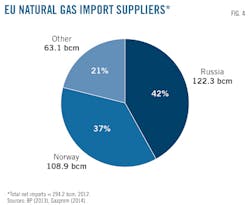

The most lucrative part of these markets is of course the European Union (EU). In 2012 total European gas demand was 443.9 bcm. The EU imported 294.2 bcm, or 66% of its consumption. Norway provided 108.9 bcm of total European imports, 24.5% of total EU consumption and 37% of total imports. According to Gazprom and BP, Russia sold 122 bcm of natural gas into the EU in 2012, 27.5% of total EU consumption and 41.4% of total imports (Fig. 4). Russia also provided 26 bcm of Turkey's annual consumption of 46.1 bcm natural gas in 2012.

Total Russian exports to Europe (EU, Turkey, and other non-EU countries) were around 150 bcm in 2012. Russia also imported 37.2 bcm of gas from Central Asia, including 9.9 bcm from Turkmenistan, which according to Gazprom was diverted to domestic Russian or Commonwealth of Independent States markets.

Infrastructure exists with a design capacity of 110 bcm/year to move Turkmen gas to Western markets, but it requires use of a pipeline network in the Russian Federation which Russia is unwilling to grant for these purposes. Russia prefers to regard Turkmen gas as part of the "common resource basis of OAO Gazprom," and to use it to provide cheap gas to other post-Soviet states while exporting its own volumes to Europe.

There are two theoretical routes that would allow Turkmenistan to transmit its gas to Turkey and further into Europe while bypassing Russia. One would go through Iran. The second would cross the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

Building pipelines to export Turkmen gas to Europe through Iran has similar problems to those faced in using it as a route to India and Pakistan. Iran is a significant gas producer, and thus a competitor, and US sanctions until recently discouraged foreign oil companies from participating in any activity involving Iran.

Building a subsea pipeline from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan remains the only commercial option. The idea of building a pipeline from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan is at least 30 years old. When Iran stopped providing gas to the southern republics of the USSR after the turmoil accompanying the Islamic revolution of 1979, the Soviet Government ordered a feasibility study in 1980 on building the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline. The collapse of the Soviet Union prevented building this pipeline.

The idea was revitalized in 1997 after it became clear that Russia would not allow Turkmenistan to use its network to export gas to Europe. This project is resisted by the Russian Federation, which fears erosion of its market share.

Russia refers to the lack of agreement on the legal status of the Caspian Sea and environmental concerns as its official reasons for opposing the pipeline. But lack of agreement on the legal status of the Caspian Sea has not prevented Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Russia itself from building dozens of kilometers of subsea oil and gas pipelines serving offshore production. And Gazprom's environmental impact study on the similarly situated Nord Stream gas pipeline across the Baltic Sea, as well as other studies, found the environmental impact of gas pipelines and incidents involving subsea gas pipelines to be minimal.

The recent deterioration of relations between the Russian Federation and the West over the crisis in Ukraine, which started in November 2013, has raised concerns in Europe regarding dependence on Russian gas imports and accordingly increased the importance of alternative sources, including Turkmenistan. This deterioration of regional security, however, might further discourage Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan from pursuing this project. Azerbaijan made a statement indirectly distancing itself from the TCGP idea and criticized the EU for exposing Azerbaijan to unnecessary risk by speculating on this project without investing enough to get it built.

Other challenges for Turkmen gas exports to Europe include competition from prospective shale gas production in Europe, possible imports from the US, increasing gas imports from Northern Africa and recently discovered Eastern Mediterranean fields off Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Cyprus, estimated to contain 736 bcm.

Interdependence

All proposed solutions to tap the huge potential of Turkmenistan's gas exports look like a zero-sum game, with irreconcilable interests between Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran. A solution will require understanding the root cause of this confrontation: the lack of an integrated global natural gas market.

Eurasia has two distinct advantages regarding natural gas:

• Vast resources; 80% of globally proven reserves are there.

• A single landmass, allowing transmission of produced gas through relatively inexpensive overland pipelines.

A large share of the internationally gas traded in Eurasia, however, still is transported as LNG, despite the lower cost of transmission through overland pipelines for distances up to 4,000 km. In 2012 alone, 36% or 301.1 bcm of the total 826.1 bcm cross-border traded gas in Eurasia was LNG, and 70% (210.9 bcm) of traded LNG originated inside Eurasia. The same year, 130 bcm (90 bcm as LNG, the rest as pipelines from North Africa), or 6% of total Eurasian consumption was imported from non-Eurasian sources.

According to IEA estimates, however, under current policies the share of gas from non-Eurasian sources in Eurasian consumption will rise to 23.3% (551 bcm) by 2035, most of which will be transported as LNG. Eurasia's share of world production will at the same time decline to 36% in 2035 from 60% in 2012. Underutilization of Turkmen reserves will play a large role in this decline, the country having the highest reserves-to-production ratio (250 years) among itself, Iran, Russia, and Qatar.

This decline in production share-from a region holding 80% of globally proven reserves-attests to serious flaws in the existing Eurasian overland gas pipeline system. Eurasia has enough gas to meet its entire demand provided it had sufficient pipeline capacity.

Cases will remain, such as imports to Japan or exports from Indonesia, where LNG will remain the most logical solution. Technological advances likely will also contribute to declining capital costs for LNG production. But there is no economic reason to not build sufficient pipeline capacity.

Access to gas pipelines and their routing, however, are interlinked impediments to development of a global gas market. The cost of building a pipeline forces producers to make certain gas will flow to a specific buyer at an agreed price. The Eurasian gas pipeline network might look vast, but it remains a sum of isolated sub-systems. Networking, liberalization of access, and diversification of routes are required to create an integrated global market.

Networking

Networking of the various Eurasian natural gas pipeline systems is already underway, but there is no concerted action among producers and consumers to build pipeline infrastructure according to economic logic. This is the case despite producers and consumers sharing the common goal of diversification.

The seasonality of gas demand and production impasses also point toward the need for an optimized network. The EU's creation of an integrated gas pipeline network using interconnectors is a promising development. Bidirectional pipelines are another promising innovation.

Access liberalization

A legally binding agreement on pipeline networks between all countries of Eurasia needs to be enacted. The treaty could address the following points:

• Elimination of obstacles to access to gas infrastructure for both suppliers and consumers.

• Issuance of tariffs for gas transmission.

• Liberalization and standardization of procedures required to change supplier or customer.

• Allowing entry of new market participants.

Pipeline ownership, or at least operation, should also be decoupled from production. The new treaty could draw upon the European Energy Charter, which provides the basis for the integrated European market.

Diversification

Regulation of any such treaty will be the biggest problem. Open access to infrastructure can only be assured by eliminating the potential for any state or entity to have a monopoly regarding supply, consumption, or transit. Abundant infrastructure, providing all market participants with alternatives, would address this issue.

Varying degrees of support for diversification already exist among key Eurasian players. The potential to cover at least part of the 551 bcm Eurasian countries expect to import from non-Eurasian sources in 2035 is a strong incentive toward creating a stable, integrated gas transmission infrastructure.

The Russian Federation's position is key. While the Russian government recognizes the goal of creating an integrated gas infrastructure, it does not yet seem willing to consider open access to it, as evidenced by its delaying ratification of the European Energy Charter.

But with the European market stagnating, and consistent efforts by the EU to lessen dependence on Russian imports, the benefits of diversification for Russia, including allowing it to export through Central Asia to growing South Asian markets, will gradually become more evident.

Turkmenistan would play a central role in an integrated Eurasian gas transmission system: its location allowing it to supply China, India, and Europe, and its reserves allowing it to play a role in stabilizing the gas system.

Bibliography

Abbasov, S., "Russia-Ukraine Crisis Spurring Azerbaijani-Turkmen Gas Export Partnership?," EurasiaNet.org, Apr. 10, 2014.

Amineh, M.P. and Yang, G., "Secure Oil and Alternative Energy: The Geopolitics of Energy Paths of China and the European Union," Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, 2012.

Amineh, M.P. and Yang, G., "The Globalization of Energy: China and the European Union, Brill, 2010.

"An Assessment of Safety, Risks, and Costs Associated with Subsea Pipeline Disposals," Scandpower Risk Management, Sept. 16, 2004.

"An Assessment of the Gas and Oil Pipeline in Europe," The European Parliament, Brussels, 2009.

"Analysis & Projections: World Shale Resource Assessments," US Energy Information Administration (EIA), accessed Apr. 20, 2014.

"Answer to a Written Question - Nabucco and the Trans-Caspian Pipeline," European Parliament, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getAllAnswers.do?reference=E-2013-000279&language=EN, Feb. 27, 2013.

Aslund, A., "Why the European Energy Charter Needs Revision," Telos, Apr. 2, 2006.

"Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Amu Darya Basin and Afghan-Tajik Basin Provinces, Afghanistan, Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan," US Geological Survey, World Petroleum Resources Project, US Department of the Interior, 2012.

"Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the North Caspian Basin, Middle Caspian Basin, North Ustyurt Basin, and South Caspian Basin Provinces, Caspian Sea Area," US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior, 2010.

"Baloch Rebels Blow Up Three Pakistani Gas Pipelines," Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Feb. 10, 2014.

"China to Provide New Loan to Turkmenistan for Galkinish Gas Field," Trend News Agency, Sept. 5, 2013.

Clarke, J., "Petroleum Geology of the Amu-Dar'ya Gas-Oil Province of Soviet Central Asia," US Geological Survey, Department of the Interior, 1988.

Collins, G. and White, B., "Tajikistan's Gas Boom: Prosperity or Conflict?", The Diplomat, June 5, 2013.

Dellecker, A. and Gomart, T., "Russian Energy Security and Foreign Policy," Taylor & Francis, Oxford, 2011.

"Energy Strategy of Russia up to 2030," Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation, Nov. 13, 2009.

"Erdogan's visit to Baku," ANS Press, Apr. 7, 2014.

Ericson, R.E., "Eurasian Natural Gas: Significance and Recent Developments," Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 53, No. 5, Sept.-Oct. 2012, pp. 615-648.

"Excerpts from the Speech Delivered to the Third Caspian Summit," President of Russia, Nov. 18, 2010.

Foster, J., "Afghanistan, the TAPI Pipeline, and Energy Geopolitics," Journal of Energy Security, Mar. 23, 2010.

"Gas Marketing in Europe," Gazprom, http://www.gazprom.com/about/marketing/europe/, accessed Apr. 28, 2014.

"Gas Marketing in the CIS and Baltic Countries," (in Russian), http://www.gazprom.ru/about/marketing/cis-baltia/, accessed Apr. 14, 2014.Guliyev, I.S, Mamedov, P.Z., and Feyzullayev, A.A., "Hydrocarbon Systems of the South Caspian Basin, Nafta-Press, Baku, 2003.

Gurt, M., "China Asserts Clout in Central Asia with Huge Turkmen Gas Project, Reuters, Sept. 4, 2013.

Gurt, M., "Reclusive Turkmenistan Ups 2030 Natural Gas Target," Reuters, Sept. 13, 2012.

Gurt, M., "Turkmenistan Started to Build Gas Pipeline to the Caspian Sea," (in Russian), Internet Gazeta Turkmenistan.Ru, Mar. 31, 2010.

Hasanov, H., "Turkmenistan Increases Raw Materials Sources for Gas Supplies to Iran," Trend News Agency, Mar. 28, 2014.

Iskakbayeva, G., "Legislative and Taxation Framework: Petroleum Operations in Turkmenistan," Deloitte, 2011, p. 51.

Jervalidze, L., "Georgia: Russian Foreign Energy Policy and Implications for Georgia's Energy Security," GMB Publishing Ltd., London, 2006.

Joseph, I., "Unlocking the Assets: Energy and the Future of the Central Asia and the Caucasus, Caspian Gas Exports: Stranded Reserves in a Unique Predicament," The James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University, 1998.

Krashakov, A., "Analysis of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline from Both Economic and Business Angles," Natural Gas Europe, Apr. 7, 2014.

"Law of Turkmenistan on Hydrocarbon Resources," (in Russian), State Customs Service of Turkmenistan, 2008.

Menon, M., "Pakistan's First LNG Terminal to Be Ready by November," The Hindu, Mar. 19, 2014.

Meyer, H., "Russia May Ship Kovykta Gas to China After Gazprom Acquisition," Bloomberg, Mar. 1, 2011.

"Oil and Gas Industry of Turkmenistan," http://www.oilgas.gov.tm/, accessed Mar. 12, 2014.

"New Trend? Bi-Directional NatGas Pipelines in Marcellus/Utica," Marcellus Drilling News, October 2013.

Nikolaeva, A. and Kashin, V., "Gas Declaration - Russia, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan reached agreement on building a new gas pipe," (in Russian), Internet Gazeta Turkmenistan.Ru, May 14, 2007.

Okimi, H., "Comparative Economy of LNG and Pipelines in Gas Transmission," World Gas Conference, Tokyo, June 1-6, 2003.

Pannier, B., "Pipeline Explosion Raises Tensions Between Turkmenistan, Russia," Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty," Apr. 14, 2009.

Reed, S. and Kanter, J., "A European Energy Executive's Delicate Dance Over Ukraine," New York Times, Apr. 27, 2014.

Rejepova, T., "Turkmenistan Sets Ambitious Production Targets Amidst Bleak Gas Sale Prospects," Central Asis-Caucasus Institute Analyst, Apr. 3, 2013.

Saivetz, C., "Perspective on the Caspian Sea Dilemma: Russian Policies Since the Soviet Demise," Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 44, No. 8, August 2003.

Savin, V. and Ouyang, C.S., "Analysis of Post-Soviet Central Asia's Oil & Gas Pipeline Issues," Geopolitika, Dec. 25, 2013.

Shahbazov, F., "Sardad or Kapaz," Strategic Outlook, July 4, 2012.

Song, Y.L., "CNPC Raises Gas Output from Turkmen Fields to Meet Chinese Winter Demand," Platts, Nov. 12, 2013.

"Statistical Review of World Energy 2013," BP, June 12, 2013.

Suleimanov, O. and Siradze, E., "Legal Status of the Caspian Sea," Colibri Law, Tbilisi, 2010.

"Turkmen, Afghan Leaders Launch Construction of TAPI Pipeline," RFE/RL Online, Nov. 10, 2015.

"Turkmenistan Economy, Politics, and GDP Growth Summary," Economist Intelligence Unit, http://country.eiu.com/Turkmenistan, accessed Apr. 27, 2014.

Ulmishek, G., "Petroleum Geology and Resources of the Amu-Darya Basin, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran," US Geological Survey Bulletin 2201-H, 2004.

Victor, D.G., Jaffe, A., and Hayes, M.H., eds., "Natural Gas and Geopolitics: From 1970 to 2014," Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006.

"World Energy Outlook 2013," International Energy Agency, Nov. 12, 2013.

Wu, J. and Cui, H.P., "China, Turkmenistan Sign Key Gas Agreement," China Daily, Oct. 24, 2011.

Ydreos, M., "Geopolitics and Natural Gas, 2009-2012 Triennium," World Gas Conference, Kuala Lumpur, June 4-8, 2012.

Zhukov, Y.M., "Border Disputes and Gas Fields in the Eastern Mediterranean, Foreign Affairs, Mar. 20, 2013.

The author

Qaya Mammadov ([email protected]) is a member of the diplomatic service of the Republic of Azerbaijan. He holds a BA in international relations from Baku State University, Azerbaijan, and an MA in diplomacy from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, Medford, Mass. Mammadov teaches on foreign policy issues at ADA University and Khazar University, Baku, Azerbaijan.