Revised Texas permitting process complicates eminent domain

Aaron Roffwarg Aaron Carpenter

Bracewell & Giuliani

Houston

Whenever condemning land for a Texas pipeline, operators have renewed cause to review the state's constitutional law while filling out the needed permit applications. Whatever one's basis for eminent domain authority is, it must comply with both the United States Constitution and the Texas Constitution. If there is no conceivable public use for a pipeline, any condemnation for its development will violate `this rule. Different legal authorities may vary their thresholds for public use, but the core concern remains the same, and the Texas Railroad Commission (TRC) has revised its permitting process in a manner designed to track that "reasonable proof of a future customer, thus demonstrating that the pipeline will indeed transport 'to or for the public for hire'" is present before any claim of eminent domain authority.1

The revised process responds to a major shift from the Texas courts. In 2011 the Texas Supreme Court surprised the state's legal observers and unsettled the pipeline industry through its interpretation of eminent domain law in the case Texas Rice Land Partners v. Denbury Green Pipeline-Texas LLC. This article examines the primary effects of that opinion: introduction of the "reasonable probability test," which determines whether a pipeline serves the public and, therefore, meets its constitutional requirement of "public use," and the TRC's response to the opinion.

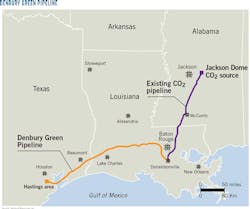

Denbury Resources Inc., a publicly traded pipeline company, wanted to build and operate a carbon dioxide (CO2) pipeline from its CO2 storage in Mississippi to supply enhanced oil recovery operations (EOR) at its Texas wells (see accompanying map).1 Transportation of CO2 not owned by Denbury was a possibility, but most evidence indicated that the portion of the pipeline to be built in Texas would be used solely to transport Denbury's CO2 to Denbury's Texas wells.1 In March 2008 Denbury applied to the TRC for permits to operate the pipeline.

The critical TRC permit Denbury needed was the T-4, which would grant Denbury authority to operate the Texas part of the pipeline. On that form Denbury could define the pipeline as either a "common carrier," "gas utility," or a "private line." Denbury chose common carrier. Denbury also answered, "No" to the question "Will the pipeline carry only the gas and-or liquids produced by the pipeline owner or operation?" Below that, Denbury checked that the gas was "owned by others, but transported for a fee."1

Denbury may have assumed that, since the gas would be owned by one Denbury affiliate and the pipeline by another it was answering the question correctly. They may also have legitimately anticipated carrying third-party gas in the future, or that tertiary oil recovery operations were themselves benefitting the public.

What is most likely, however, is that Denbury didn't think about it too much at all, due to the prior practice of the TRC and the fact that then-current case law held submission to the public regulation of the TRC as sufficient to meet the Texas Constitution's public use requirement. The company submitted the standard letter and completed T-4 to the TRC stating it accepted the provisions of Chapter 111 of the Natural Resources Code. The TRC approved its application 8 days later without a hearing and without notice to landowners along the route, as was common practice.1

But one of the landowners-Texas Rice Land Partners-did not want the pipeline to run through its land. It and its lessee denied entry to Denbury's surveyors attempting to plot the course of the pipeline. Denbury sued for an injunction to provide its surveyors access and was granted summary judgment by Justice Floyd in Jefferson County District Court. Texas Rice appealed, but the Beaumont Court of Appeals affirmed the decision.1

On Texas Rice's subsequent appeal to the Texas Supreme Court, however, the high court issued an opinion that significantly altered this area of state law. The Court held that the mere granting of the T-4 permit by the TRC to Denbury, along with the facts supporting the designated purpose of the pipeline, were insufficient to establish that Denbury was a common carrier with the power of eminent domain, which under the Texas Constitution always requires proof of public use.1 Going further, the court defined this public use as a test (the reasonable probability test) requiring that a "reasonable probability must exist that the pipeline will at some point after construction serve the public by transporting gas for one or more customers who will retain ownership of their gas or sell it to parties other than the carrier."1 The court went on to say that, under the statute, a pipeline owner cannot be considered a common carrier if the pipeline's "only end user is the owner or an affiliate."1 The court did not define affiliate, but simply underscored that they would look at substance over form when applying the test.

The Supreme Court then returned the case to Jefferson County District Court to decide whether the facts met that threshold, but not without first voicing its displeasure regarding the TRC's T-4 process: "Given this scant legislative and administrative scheme, we cannot conceive that the Legislature intended the granting of a T-4 permit alone to prohibit a landowner-who was not a party to the Commission permitting process and had no notice of it-from challenging in court the eminent-domain power of a permit holder."1

This holding brought uncertainty to a previously clear eminent domain legal framework, introducing three particular unknowns:

• To what sorts of pipelines the reasonable probability test would apply.

• How the TRC would alter its permit process.

• What factual circumstances would satisfy reasonable probability.

Eminent domain and two constitutions

For an exercise of eminent domain to be constitutional, both the statute granting the exercise of eminent domain and the application of the statute by the specific facts must be compliant with the relevant portions of the US and Texas Constitutions.

The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution limits the exercise of eminent domain by federal and state governmental entities (and private entities specifically granted the authority to exercise eminent domain) to takings that are for a public use and pay the property owner just compensation.2

Litigation has broadened the public use requirement's definition to a point that its relevance to this discussion is limited. Most recognizable of these cases is the 2005 United States Supreme Court case Kelo v. City of New London.3 The Supreme Court held that a taking from one private owner to give to another for the purpose of economic development constituted a public use under the US Constitution. This holding was regarded as a significant loosening of the public use requirement and alarmed property rights activists.4 The holding, however, did not prevent state constitutions and legislatures from enacting more significant protections for property owners, which soon occurred in Texas.4

The Texas Constitution also limits governmental takings to those that are both for a public use and accomplished by state action, the public at large, or an entity granted the power of eminent domain.5 The Texas public's concern over the Kelo decision led to an emergency legislative action in which both houses of the legislature passed Texas Senate Bill 18, which changed various provisions of various Texas codes that grant the power of eminent domain.6 This bill emphasized that government agencies could only exercise eminent domain powers to bring about a public use.6 While the statue did not define public use, commentators saw it as attempting to ensure that eminent domain was actually being used to accomplish a public function as opposed to achieving private gain.6 These protections displayed the growing awareness of the ability of a plain reading of public use to protect private property rights.

No governmental taking-from any state statutory source-will be valid if these provisions are violated, even if it seemingly complies with the statute. The Denbury opinion addressed this head-on: "The Texas Constitution safeguards private property by declaring that eminent domain can only be exercised for 'public use.' Even when the Legislature grants certain private entities 'the right and power of eminent domain,' the overarching constitutional rule controls: no taking of property for private use."1

Texas courts ultimately decide the extent of the public-use requirement. But statutes implementing eminent domain power are binding on courts "unless it is manifestly wrong or unreasonable, or the purpose for which the declaration is enacted is 'clearly and probably private.'"7

Texas statutes

Pipeline operators are granted eminent domain authority under Texas law from four different sources:

• Texas Natural Resources Code.

• Texas Utilities Code.

• Texas Business Organizations Code.

• Common law.

The most commonly claimed statutory source for pipeline eminent domain takings is Texas Natural Resources Code §111.019(a), which grants the power of eminent domain to pipelines designated as "common carriers."8

The code provides seven possibilities for this "common carrier" designation. Four of these provisions give rules for crude oil, with others providing guidelines for coal, carbon dioxide or hydrogen, and feedstock or other products. The accompanying box shows excerpts related to crude and certain gases. The language "to or for public for hire" ensures that any takings according to this statute are accomplished for a public use and therefore constitutional.

These statutes were at issue in the Denbury decision, yet that court expressly limited its opinion to CO2 pipelines, as stated in Texas Natural Resources Code §111.02(6).1 This provided little comfort for those claiming eminent domain authority under other provisions of Tex. Nat. Res. Code §111.02, as it did not provide a rationale for such confinement. It is possible the Court displayed caution on the issue because it was not raised by the parties or extensively briefed.

Two Texas Courts of Appeals have already disregarded the initial court's limitation. In Crawford Family Partnership v. Transcanada Keystone Pipeline, the Texarkana Court of Appeals said it was "not persuaded by the Court's reasoning that the process of obtaining a T-4 permit applies only to carbon dioxide lines."9

The Beaumont Court of Appeals, in Crosstex NGL Pipeline L.P. v. Reins Road Farm-1, Ltd., then cited the TransCanada case and agreed that the reasonable probability test should apply to additional sections in the Natural Resources Code.10 The Beaumont court also noted in Rhinoceros Ventures Group Inc. v. TransCanada Keystone Pipeline that the Denbury court only addressed the issue of CO2 pipelines.11 Despite this possible inconsistency, these holdings, along with the scant rationale in the original opinion for the pigeonholing, make it likely the reasonable probability test will apply to those provisions of the Natural Resources Code designated "to or for public for hire."

The Texas Utilities Code grants natural gas pipeline operators eminent domain. Tex. Util. Code §181.004 grants a "gas corporation" the power to condemn for an easement. It defines a gas corporation by looking at the definition of "gas utility" in Tex. Util. Code §121.001(a)(2), since the term "gas corporation" isn't specifically defined, as an entity that "owns, operates, or manages a pipeline for the purpose of carrying natural gas for public hire or not, and the right-of-way is acquired by exercising the right of eminent domain."12

Some commentators maintain that the "for public hire or not" clause in the relevant sections of the code distinguishes this authority from its counterpart in the Natural Resources Code.13 Texas Utility Code §121.001(a)(2) is explicit in granting broader eminent domain power. But notwithstanding the text of Tex. Util. Code §121.001(a)(2), the law is always subject to the "public use" requirement of the Texas Constitution.

Texas courts may hold, as they did in Coastal States Gas Producing Co. v. Pate, that the constitutional "public use" requirement is met because of the "direct, tangible, and substantial interest and right in the undertaking" of certain natural gas lines.14 In addition, deference will be given to the legislature: "a legislative declaration that a use is public...is to be given great weight by the court in determining whether a particular use is public or private."15

Nevertheless, this deference does not foreclose the possibility that the reasonable probability test or a derivative thereof will apply to gas pipelines. If a gas corporation was merely moving its commodity via a pipeline from one affiliate to another, it is hard to discern a distinguishing principle that would allow it more protection than, say, crude pipelines exercising authority under the Natural Resources Code. Explanations for the constitutionality of condemnations under the Utilities Code, in fact, are very similar to the pre-Denbury framework under the Natural Resources Code; namely that submitting oneself to the authority of the TRC is sufficient.16

The most recent case on the issue is Mercier v. MidTexas Pipeline Co., where the Corpus Christi Court of Appeals allowed a partnership, operating as a "gas corporation" under the statute, to condemn land between two partners.17 The court's rationale for a public purpose in the case included the fact that no previous challenges to an entity's power of eminent domain under the Utilities Code had been successful.17 The Texas Supreme Court in Denbury had similar precedent.1 Mercier's final citation was Coastal States Gas Producing v. Pate, which stated that "this court has adopted a rather liberal view as to what is or is not a public use."17

That does not hold true after Denbury: the view from the bench at the Texas Supreme Court has changed, and pipeline operators condemning under the authority of the Utilities Code would be unwise to ignore the possibility that the reasonable probability test or a similar construct could apply.

The Texas Business Organizations Code is another potential source of eminent domain authority. In somewhat confusing fashion, Texas Business Organizations Code §2.105 states: "In addition to the powers provided by the other sections of this subchapter, a corporation, general partnership, limited partnership, limited liability company, or other combination of those entities engaged as a common carrier in the pipeline business for the purpose of transporting oil, oil products, gas, carbon dioxide, salt brine, fuller's earth, sand, clay, liquefied minerals, or other mineral solutions has all the rights and powers conferred on a common carrier by Sections 111.019-111.022, Natural Resources Code."18

While the inclusion of materials such as salt brine and fuller's earth distinguish this provision from those in the Natural Resources Code, it remains uncertain whether this should be considered a separate grant of power or merely the same grant as the alternate statute. The Texas Business Organizations Code also does not specifically define "common carrier." Its provisions incorporate a limited portion of the Natural Resources Code, effectively eliminating guidelines for rates, abandonment, and other features of that statute.19

Until more cases citing this source are tried, its role remains uncertain. On remand, the Beaumont Court of Appeals held that an entity must be a common carrier to use Texas Business Organizations Code authority, but this approach has not been ordained statewide.17

Texas common law also provides that "a common carrier is one who holds himself [sic] out to the general public as engaged in the business of transporting persons or property from one place to another" and must owe those being transported a high duty of care and a lack of unjust discrimination.19 This is rarely relevant in the pipeline context.

New TRC regulations

The TRC addressed the Denbury decision 3 years later when it responded to the Texas Supreme Court with rule amendments to the relevant Texas Administrative Code section: 16 Tex. Admin. Code §3.70. In the memorandum accompanying those amendments, the agency underscored its limited duties in the T-4 permitting process: "The Commission has neither the power to require, approve, or deny the building of a pipeline along a particular route nor the power to determine what rights the landowners along that route might or might not have. The Commission's duty is to determine the proper classification of a pipeline and thereafter to apply its rules and regulations to that pipeline. Litigation over the rights of a property owner or a pipeline's easement is not a Commission matter; it is a courthouse matter."25 The TRC, therefore, would function like a clerk, ensuring the process around filing the permits is proper, but refusing to conclude that the evidence attached to the application is enough to constitute public use.

Amendments to 16 Tex. Admin. Code §3.70 altering this process, however, were significant. Pipeline operators must still file a T-4 form to operate a pipeline and also submit a sworn statement providing the operator's factual basis supporting the classification and purpose being sought for the pipeline, including supporting contact information and documentation.22

While it is unclear whether the TRC's initial review of these applications will be more stringent, the new process burdens the pipeline operator to provide documentation supporting the proposed classification. Should the T-4 permit then be put under more significant review by the TRC (in an unprecedented revocation proceeding, for example) or a court, sworn statements made by the applicants would be on record and damaging if incorrect or fraudulent. These changes took effect Mar. 1.

The most critical and confusing requirement set forth in the amendments relates to the 3.70(b)(3) requirement ((b)(3) Requirement) to provide "the factual basis supporting the requested classification and purpose of the pipeline system as a common carrier, gas utility, or private line." This requirement will likely change in substance depending on the classification desired.

It is safe to assume that if a pipeline applicant classifies itself as a common carrier pursuant to its T-4 permit, the (b)(3) Requirement requires the applicant to satisfy the Denbury court's reasonable probability test,1 including a declaration that the pipeline will serve the public by transporting the applicable product for unaffiliated customers who will either retain ownership of such product or sell it to parties other than the carrier. Operators may consider attaching transaction descriptions, redacted contracts, evidence of open seasons, and proof of long-range planning supporting the fact that there is a reasonable probability of third-party product transport.

What is less clear is what information should be provided to support a gas utility classification under the (b)(3) Requirement. Documentation supporting the fact that the applicant meets the definition of a gas utility ("an entity that owns, operates, or manages a gas pipeline for hire or not") pursuant to Tex. Util. Code §121.002(a)(2) clearly is required. A prudent gas utility pipeline applicant, anticipating it may want to exercise eminent domain powers, might also consider providing documentation demonstrating how the pipeline will serve the public, since the public-use constitutional requirement applicable to the common carrier could apply to a gas utility.

Unchanged by these amendments is the fact that property owners may only act to prevent condemnation through the courts; there is no specific administrative mechanism by which third parties can challenge common carrier or gas utility status within the TRC.28 Also, as of the date of this article, there are no specific safe harbors or guidelines under the new TRC regulations. Pipeline companies will simply need to find documents and affidavits that best support their chosen pipeline classification,26 creating uncharted territory for both lawyers and operators. Approaches will likely vary widely until best practices are established.

Among the denied commenter recommendations from this rulemaking were:

• Adversarial testing.

• Standards of proof for common carrier status.

• Standards for revoking common carrier status.

• Public notice and hearing requirements.

• Staffing fees.

• An extended timeline.26

These recommendations were not unusual, as other areas of condemnation law in the state-relating to power lines, for instance-require similar protections. The refusal to provide such protection to landowners reflects both a concern that the TRC's enabling statute does not permit it to take certain actions and knowledge of the agency's institutional capability.26

Reasonable probability test

A trio of Texas Court of Appeals cases, including the remand of Denbury itself, provide guidance to operators regarding which facts meet the reasonable probability test.

In the Texarkana Court of Appeals, Crawford Family Partnership v. TransCanada Keystone Pipeline had facts similar to the Denbury case: TransCanada was attempting to condemn the property, the landowner refused, and litigation ensued. The court held that TransCanada met the reasonable probability test as it filed an affidavit with the court that described the relevant project, which would "transport crude petroleum owned by third-party shippers unaffiliated with Keystone or Keystone's parent companies or affiliates." The court also noted that there was an open season at an Oklahoma connection point where various third parties had transportation and throughput agreements. Third parties shipping their crude in the pipeline also would retain ownership of the crude. As no evidence was provided to dispute this affidavit, the reasonable probability test was met.13

In contrast, the Beaumont Court of Appeals in Crosstex NGL Pipeline v. Reins Road Farm-1 upheld the trial court's finding that the reasonable probability test was not satisfied.12 To support this holding, the court noted that:

• Crosstex could use the entire capacity of the pipeline (in this case transporting NGLs).

• Efforts to obtain unaffiliated customers for the pipeline were unsuccessful.

• Crosstex's contracts with third parties each required Crosstex to purchase the NGL liquids before they entered the pipeline.

Sufficient evidence was therefore available for the trial court to determine that Crosstex was not a common carrier.12

The eventual result of Denbury on remand in the Beaumont Court of Appeals added another layer of complexity. The court held that the reasonable probability test applied to an operator intending to build a pipeline, emphasizing that courts should ignore (or downplay, as applicable) both potential contracts and customers that approached the operator after the construction of the pipeline had begun. The court also hinted that insignificant potential third-party customer contracts may not meet the necessary substantiality threshold, underscoring that certain Texas courts will not shy away from a fact-intensive scrutiny of an operator's underlying public-purpose rationale.

Adding to this uncertainty is the fact that "affiliate" is not defined in the Texas Natural Resources Code and was only given cursory treatment in the original Denbury opinion. On Denbury's motion for a rehearing, Justice Dale Wainwright wrote a concurrence opinion summarizing Texas law on the issue.26 He mentioned that "just one share" is not sufficient, referring to the following statutes as potential models:

• The definition of a "common purchaser" in Natural Resources Code §111.081 as "affiliated through stock ownership, common control, contract, or in any other manner" (there are also regulations defining "affiliate" as "effectively controlled by another").

• Provisions in the Texas Administrative Code that prescribe triggers at various ownership percentages.

• The Texas Utilities Code, which focuses on "operational control" in §111.004.

Operators should review those provisions before claiming their operations with affiliates conform to any safe harbor regarding public use.

Trends, context

The shift in Denbury is part of a broader trend, with property rights advocates having significant sway in the Texas political arena. Both the state's voters and their representatives have been explicit in their defense of private property rights in recent decades. The Republican Party, especially, has gained popularity by addressing these concerns, gaining majorities in the legislature and the Texas Supreme Court, which hasn't had a Democratic justice since 1998.20

Even with this representation in place, however, the public sometimes displays grassroots opposition, pointing towards the possibility that further protections may be enacted to protect Texas landowners.

The administration of Gov. Rick Perry (R) proposed the Trans-Texas Corridor-4,000 miles of toll roads, railroads, and utility lines built over 50 years at a projected cost of $175 billion21-to promote economic development, provide public transit, enable trade routes, and increase development in ignored parts of the state.22 The project ended up limited and divided in response to concerns about property rights, foreign control, and what was viewed as an attack on rural Texas, and "by 2011, the legislature had erased every mention of the Trans-Texas Corridor from Texas statutes and nearly every word of the original legislation authorizing the project."22 While elements of the plan may still be developed, lawmakers are careful to frame any such projects in a manner less overtly threatening to landowners.

Statewide attention returned to common carriers in spring 2015, when Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) filed a T-4 permit with the TRC to build the Trans-Pecos pipeline from Pecos County, Tex., to the border at Presidio, Tex., from where it would ship natural gas into Mexico.23 ETP's local informational meetings addressed the concerns of more than 200 attendees regarding the sanctity of their property rights, the pipeline's safety, and the impact of the development on the area's ecosystem and tourist appeal.24 While ETP's T-4 was in place before the new rules took effect, the outcry surrounding the proposal highlights that concerns over property rights and common carriers remain prevalent. Activist groups also understand they can seriously delay pipeline approval, creating short-term leverage even if the operators ultimately are granted authority to condemn the land.

References

1. "Texas Rice Land Partners, Ltd. v Denbury Green Pipeline-Tex., LLC," 363 S.W.3d (Tex. 2012), Mar. 2, 2012.

2. United States Constitution, Amendment V.

3. Kelo v. City of New London," 545 US 468 (2005), June 23, 2005.

4. Woodward, W. and Boggs, G., "Public Outcry: Kelo v. City of New London -A Proposed Solution," Vol. 39, No. 2, Lewis & Clark Environmental Law Journal, Spring 2009.

5. Texas Constitution, Article I, Section 17.

6. Brown, R.F., "Eminent Domain after Senate Bill 19," Texas City Attorneys Association Summer Conference, South Padre Island, Tex., June 6-8. 2012.

7. "Tenngasco Gas Gathering Co. v. Fischer," 635 S.W. 2d (Tex.Civ.App.--Corpus Christi 1983, writ ref'd n.r.e.).

8. Texas Natural Resources Code Annotated, §111.019(a)(West 2011).

9. "Crawford Family Farm Partnership v. TransCanada Keystone Pipeline," 409 S.W.3d (Tex..App.-Texarkana 2013), Aug. 27, 2013.

10. "Crosstex NGL Pipeline L.P. v. Reins Road Farm-1, Ltd.," 404 S.W.3d (Tex..App.-Beaumont 2013), May 23, 2013.

11. "Rhinoceros Ventures Group Inc. v. TransCanada Keystone Pipeline," 388 S.W.3d (Tex..App.-Beaumont 2012), Nov. 29, 2012.

12. Texas Utility Code Annotated, §181.004 (West 2011), Texas Utility Code Annotated, §121.001(a)(West 2011).

13. Freeman, J.A. and Zabel, T.A., "Supreme Court Landowner Condemnation-Industry Perspective after Denbury," CLE, 2013.

14. Coastal States Gas Prod. Co. v. Pate," 309 S.W. 2d (Tex. 1958).

15. "Tenngasco Gas Gathering Co. v. Fischer," 653 S.W.2d (Tex. App.-Corpus Christi 1983, writ ref'd n.r.e.).

16. "Mercier v. MidTexas Pipeline Co.," 28 S.W.3d (Tex. App.-Corpus Christi 2000, pet. denied), Sept. 28 and Oct. 5, 2000.

17. "Denbury," 2015 Tex. App. LEXIS 1377 (Tex.App.-Beaumont 2015), Feb. 12, 2015.

18. Texas Business Organization Code Annotated, Section 2.105(West 2011).

19. "Bennett Truck Transport v. Williams Bros.," 256 S.W.3d (Tex. App.-Houston [14th Dist.] 2008), May 22, 2008.

20. Robbins, M.A., "Gonzalez to step down from the Texas Supreme Court," Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, Oct. 1, 1998.

21. Batheja, A., "Tolling Texans: Impact of Trans-Texas Corridor Lingers," Texas Tribune, December 3, 2012.

22. Texas Administrative Code, Title 16, Part 1, Chapter 1, Rule §3.70.

23. Malewitz, J.,"In Pristine Big Bend, a Pipeline Could Run Through It," Texas Tribune, July 14, 2015.

24. Jervey, B., "Showdown in Trans Pecos: Texas Ranchers Stand Up to Billionaires' Export Pipeline," Desmog, May 31, 2015.

25. "Memorandum of Adoption of Amendments to 16 TAC §3.70, relating to Pipeline Permits Required," Texas Railroad Commission, Gas Utilities Docket No. 10366, July 25, 2014.

26. "Denbury" concurrence, No. 09-0901, (Wainwright, J., concurring) (Tex. 2012), Aug. 17, 2012.

COMMON CARRIER

A pipeline is a common carrier subject to the provisions of Texas Natural Resources Code §111.019(a) if it:

(1) owns, operates, or manages a pipeline or any part of a pipeline in the State of Texas for the transportation of crude petroleum to or for the public for hire, or engages in the business of transporting crude petroleum by pipeline;

or

(6) owns, operates, or manages, wholly or partially, pipelines for the transportation of carbon dioxide or hydrogen in whatever form to or for the public for hire, but only if such person files with the commission a written acceptance of the provisions of this chapter expressly agreeing that, in consideration of the rights acquired, it becomes a common carrier subject to the duties and obligations conferred or imposed by this chapter.

The authors

Aaron Roffwarg ([email protected]) is a partner at Bracewell & Giuliani LLP in the Houston office. He holds a bachelor's degree from The University of Texas at Austin, and a JD from The University of Texas School of Law. He is a member of the State Bar of Texas and the Houston Bar Association.

Aaron Carpenter ([email protected]) is an associate at Bracewell & Giuliani LLP in the Houston office. He holds a bachelor's degree from Duke University, Durham, NC, and a JD from University of Virginia School of Law.