Optimized logistics ease burdens of unconventional growth

Asuquo Edem

Shell Oil Co.

Houston

The US energy sector is experiencing unprecedented growth from the accelerated development of unconventional resources like shale oil and gas.

According to the US Energy Information Administration's Annual Energy Outlook 2014 Early Release Overview, domestic crude oil production will level off and then slowly decline after 2020. Natural gas production will grow steadily, with a 56% increase during 2012-40, when production reaches 37.6 tcf.

The main catalyst for growth has been technological innovation. Technical advancement has progressed to a degree that, in the unconventional shale subsector of the oil and gas industry, some major operators are treating the oilfield as a manufacturing process.

One of the side effects of unconventional energy growth is the simultaneous growth in transportation volume. In addition to the benefits of more jobs, stronger economies, and greater energy security, the increased drilling activity has contributed to a flood of traffic that has, in turn, contributed to increased serious accidents and vehicular deaths.

As a critical component of the supply chain, well-managed logistics can mitigate the impact of this risk. Operators, however, may not have the right logistics model to control and manage the growing transportation activities.3

This article builds on the work of Deloitte consultants Rick Carr, David Wedemeyer, and Sam Pearson, who have summarized the state of logistics in the unconventional sector (OGJ, July 2, 2012, p. 65).

They found that oil and gas operators lack a central focus on transportation and logistics for onshore operations, often pushing the coordination of logistics to service providers or personnel in the field.

Given the increase in operational demands due to unconventionals, the authors recommended operators consider a more focused approach to wellsite logistics. This approach would address safety, cost, and productivity by formalizing the management of transportation and logistics associated with their wellsites.

The authors outlined six steps for wellsite logistics: establishing stronger relations with fewer carriers, implementing focused safety standards, establishing field logistics management, setting performance standards and reporting progress, centralizing transportation coordination, and introducing technology-enabled logistics management.

This article uses work by Shell Upstream Americas' logistics division to validate the central argument of the Deloitte study. It also extends the focus beyond wellsite drilling to account for other triggers of transportation activities in unconventional development.

Furthermore, using insights from Shell's experience, we will argue that the need to improve safety performance is key to professionalizing logistics in the unconventional business. Health, safety, and environment (HSE) considerations should feature prominently in the decision on what logistics-delivery model operators choose to adopt.

License to operate

Unconventional development can alter public sentiment regarding oil and gas activities, threatening the social license to operate.

Recognizing the need responsibly to develop abundant unconventional shale and gas resource, the International Energy Agency in its 2013 report proposed a set of golden rules to guide unconventional oil prospecting with one area of concern being unacceptable environmental and social damage.

This concern with environment and the social impact of oil and gas prospecting activities is a major component of many operators' operating philosophy and corporate responsibility. But the public is not always aware of that commitment companies make, and the companies themselves can sometimes fall short of their stated goals.

The growth of unconventionals means development affects more people and communities.

Road-transport impact

In addition to the potential environmental and health risks of fracking itself, heavy truck traffic imposes substantial external costs on nearby residents. These include damaged roads, noise pollution, and a correlated increase in road-traffic accidents.1

Road-transport impact goes beyond inbound and outbound flows for goods and services. Drilling, completions, and construction require a large number of crews. Most of the crew members commute individually, adding to the traffic congestion and risk exposure.

Some operators are trying to mitigate this impact by better managing work shifts, moving fabrication off site, and modularizing work, reducing the number of site workers and the road traffic associated with them. They are also encouraging bussing and carpooling for worker commutes.

Community-budget impacts

In addition to the potential impact on public safety, unconventional oil activities could have cost and budgetary implications for communities. Local roads are generally designed to support passenger vehicles, not heavy trucks. The useful life of a roadway is directly related to the frequency and weight of its truck traffic.2

While it is true that some operators work out compensation with local authorities to redress infrastructure damages, the point remains that better logistics management can help reduce the potential for, and magnitude of, this impact.

Field logistics coordination

It is against this backdrop that Shell has approached managing unconventional logistics in North America with a view to reducing overall road exposure and, thereby, potential for actual incidents.

The Shell experience in this regard will be discussed in the context of centralizing field-logistics coordination, introducing and monitoring road-transport standards, and implementing a 4PL logistics model.

The 4PL model further professionalizes logistics management and introduces the necessary technology and expertise to enhance transportation efficiencies and safety.

Phased implementation

As argued in the Deloitte study, introduction of a field-logistics-coordination model for the wellsite is a major change in the drive towards effective transportation management.

A typical unconventional asset has more going on than just wellsite activities. The major functional components include: wells-both drilling and completions, and projects-such as facilities and civil construction, and production operations.

All these functions generate significant logistics and transportation needs. When coordinating logistics, companies should look at all of their assets and find areas in which synergies exist, such as common carriers, and can be grouped together to reduce costs and risk exposure.

For example, a flatbed truck deployed to deliver equipment for a project can in turn be used to haul back a piece of rental equipment from a wellsite without the need to deadhead an empty truck for this purpose.

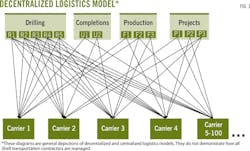

Shell implementation of centralized logistics in the unconventional oilfield began with a pilot in 2009. Before setting up the coordination cell, a field survey conducted to assess transportation flows revealed that less than 10% of field logistics were being coordinated. There was a higher volume of transportation movements than was necessary (Fig. 1).

In this figure, there are five drilling rigs in the unconventional asset, two ongoing frac packages, three producing wells, and three ongoing construction and civil works projects.

In the then-decentralized model, each drilling foreman and other on site workers were making separate and independent calls to different carriers with limited or no coordination.

As the Deloitte study highlighted, when hiring transportation carriers, the drilling foremen obtained the delivery of equipment and services through recommendations or personal preferences. The result was that there could be as many preferred carriers as there were foremen, superintendents, and other crew workers authorized to call for trucks.

Apart from the obvious cost implication of this approach, the result is poor utilization of trucking capacity. There is a higher than necessary volume of truck transportation and, consequently, higher risk of accidents and increased environmental damage and pollution.

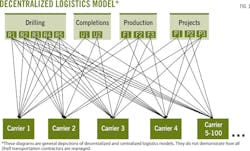

To develop an acceptable model, the review team, site-level operations personnel, and carriers and vendors that supply equipment to the site met to consider several options. The most viable solution was the introduction of a field-based logistics coordinator who served as a middle man between the various businesses with trucking requirements and the carrier base (Fig. 2).

The field-coordination model adopts a dual approach in collating transportation requirements: reactive and active.

From the reactive standpoint, coordinators receive calls, emails, or work plans requesting trucking services. Transactional problems can occur when the volume of calls becomes overwhelming.

To mitigate these problems, coordinators adopt a more active approach. They reach out to key customers and participate in morning operations calls. In this way, they determine trucking needs earlier and position themselves to plan ahead.

With foreknowledge of operational activities, the coordinators predict transportation needs based on the work stage. Eventually, as demand patterns stabilize, regular schedules are built for predictable requirements.

Logistics coordination cells

After the pilot, Shell adopted the field-logistics-coordination model and spread it to other assets in Canada and the US. By the end of 2011, most of Shell's unconventional operating assets had a field-based logistics coordination cell.

During implementation of these cells, it became obvious that, with so many carriers, there had to be a heightened focus on road-transport standards and the overall driving-safety culture in the oilfield.

Road-transport-safety specialists were deployed to the field in 2010. They assessed each carrier to identify gaps in safety standards and protocols then worked with the carrier to close the gaps as specified by government regulations and Shell standards.

Training sessions were arranged to address load security, driver qualification and competence, site-orientation expectations, short-service employee policies, and use of personal protective equipment.

Road-transport forums re-emphasized safety expectations and had carriers take the lead in presenting best practices gleaned from incidents or near misses. The goal of these forums is to develop the mindset that safety is a collective benefit and not just a competitive advantage.

Professionalized logistics

The centralization of logistics and renewed focus on road-transport safety were a success, but there were additional steps needed to professionalize fully the logistics operation.

In the Deloitte study, the authors highlighted the need for technology-enabled logistics management. This is especially true for larger organizations with an extensive carrier base for which carrier-performance management is needed.

One option is to outsource logistics support to a fourth-party logistics (4PL) organization.

According to Accenture PLC, the company that coined the term, a 4PL is an entity outside an organization that assembles and integrates capabilities from other third-parties to achieve efficiencies unattainable by the organization on its own.

The 4PL model is broad and has been used successfully in a number of industries. It touches on cost improvement, operational and service reliability through the use of systems resources, and application of lean principles in logistics optimization. We will focus on the impact 4PL has had in the management of transportation-related HSE risk in unconventional logistics.

Shell worked with its 4PL partners to tailor what had worked in other industries to fit the more unpredictable unconventional supply chain.

Shell's first implemented 4PL in Oman in 2004. It has since spread to other parts of Shell, including its unconventional business in North America.

The first North American 4PL model was implemented in late 2011 and currently the company has three 4PL partners in its Canada and US operations: Menlo Worldwide Logistics, Ryder Logistics, and Schneider Logistics.

Benefits of professionalization

The professionalization of logistics has helped Shell optimize costs and allowed personnel the time to focus on core wellsite and production activities, improving productivity and HSE focus. The greatest impact has been on transportation risk.

From January 2011 to June 2014, the logistics coordination team in the US and Canada trucked more than 75 million miles that included more than 850,000 truck trips.

Through optimization that included scheduling efficiencies, load consolidation, and the effective use of backhaul strategy, Shell eliminated more than 50,000 truck trips and avoided an estimated 8 million truck miles.

With these reductions, there is less impact on the communities in which Shell does business and, what is thought to be, a smaller carbon footprint associated with truck driving.

Similar improvements have been seen in the rate of Shell road-traffic incidents, which have declined each of the last 3 years and are on track to be reduced by more than 50% by yearend 2014.

The most dramatic improvements have been in lowering the number of trucks running off the road and trucks rolling over. Each has been reduced by about 65% during 2012-14, according to internal Shell metrics.

There is still more work to be done. Shell's efforts in this area will continue and we hope to see even more improvement.

Industry-level focus

A uniform approach to managing logistics in unconventionals is unlikely because different operators have different circumstances and preferences. There are some common areas, however, in which a coordinated industry approach could benefit all.

The increase of road traffic accidents is a source of concern, and there are steps we can take as an industry to reduce them.

One is to devise operational-logistics execution models that reduce trucking exposure. This could be done through more effective coordination as was outlined in the Deloitte study. Also, useful insights could be drawn from the Shell field-coordination model.

At a strategic level, operators could look to transfer water by pipeline rather than trucks. An intermodal logistics approach could be taken as well, in which there is a combination of rail, transloaders, and water barges for bulk materials such as sand, water, chemicals, and tubulars.

A drawback to the intermodal approach is the large capital outlay some ownership models require. This is an area in which industry collaboration could occur and costs could be shared.

Focusing on industry-level minimum standards for oilfield trucking companies, is another step. There are already statutory regulations from the government such as those issued by the US Department of Transportation and Canadian authorities. The industry, however, can consider reinforcing these with a stronger focus on compliance.

In addition, operators should consider focusing on changing safety behaviors in the field. A concerted emphasis by all operators on compliance with existing statutory standards on use of safety belts, use of personal protective equipment, maintenance protocols, drivers' duty hours, and load security will go a long way toward achieving a strong safety culture.

The risk of not having an industry-wide compliance approach is that some carriers will simply find a more lenient operator that fits their own lax safety standards. Some carriers simply refuse to work for some operators because compliance expectations are perceived to be too strict.

Industry forums like those in the Marcellus in Pennsylvania and the Permian basin in Texas are particularly effective for collaboration. In the Marcellus, the Appalachian Shale Transportation Safety Group, which was initiated by one of the major oil companies, is working on standardizing road-transportation safety and sharing safety best practices aimed at reducing safety incidents.

In the Permian basin, the Road Transport and Oil and Gas specialty segments of the American Society of Safety Engineers also focus on improving overall road transport safety.

What is currently missing from these forums is committed involvement from operators and the willingness to be accountable to each other.

Industry-wide 4PL

The final area of focus is the potential shared use of 4PL. This could begin with individual operators working independently to select their own preferred 4PL partners. Over time, and through the process of natural selection, the 4PL landscape could see only a handful of capable 4PLs operating.

This would offer an opening to implement industry-level support, as legally permitted, where trucking synergies exist. In this model, a few 4PL operators could manage the trucking needs of multiple operators in a common geographic area, increasing benefits and reducing costs. This could be through the use of common cross-docking facilities or distribution centers, a common practice in other industries with multi-customer bases.

In downstream, where trucking demand-flows bear some similarity with the broader retail industry, logistics and supply-chain management are much more advanced. They use more modern logistics processes.

The upstream, with a more complicated, less-defined, and less-predictable demand chain, does not yet have mature 4PL culture embedded. Only a handful of the more sophisticated oil-services companies that support the industry feature some version of the 4PL model.

As the 4PL model gains further traction and popularity in the upstream sector, including unconventionals, an industry-level model could evolve. Some leading 4PL organizations are developing strategies for this sector, which could affect common industry-safety standards and provide a collective reduction in safety and environmental risk exposure.

There are barriers to implementation of an industry-level model. With the different sizes of operators and operations in unconventionals, smaller independents could have different approaches to logistics than the larger companies. Even operators of similar scale could have fundamentally different approaches to logistics management.

At a minimum, emphasizing compliance with existing statutory standards aimed at promoting a common industry trucking safety culture must be considered. This could be reinforced by strong messaging on safety values and creating enforcement mechanisms, as leagally permitted, to hold noncomplying carriers accountable.

Troubling non-compliance

Data show that standards compliance is still an issue. A January 2013 survey report by the US Department of Transportation's National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (DOT 811 875) shows that, in 2013, overall use of seat belts across the country was 87% and for commercial motor vehicles s, including oil-field trucks, it was 83%.

Shell has developed driving-related rules to focus on this basic level of non-compliance. These rules include mandatory use of seat belts, not using cell phones or other devices during driving, and observing speed limits. Noncompliance can result in termination from Shell. Broadly, compliance with standards can be a springboard for industry-level collaboration. Operators can formalize, centralize, and coordinate transportation activities by setting standard operating procedures that will force coordination efforts.

References

1. Begos, K., "Traffic Accidents Are a Deadly Side Effect of Fracking Boom," Associated Press, May 5, 2014.

2. Abramzon, S., Samaras, C., Curtright, A., Litovitz, A., Burger, N., "Estimating the Consumptive Use Cost of Shale Natural Gas Extraction on Pennsylvania Roadways," Journal of Infrastructure Systems, Vol. 20, No. 3, September 2014.

The author

Asuquo Edem ([email protected]) is the manager, unconventional logistics, for Shell Oil Co. He holds a PhD in industrial relations and an MBA in supply chain management from Leicester University, UK. Edem is certified with the UK Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply, the Supply Chain Association of Canada and the Institute of Supply Management, US.