New Russian export regime will spur ULSD exports

Andrew Reed

ESAI Energy LLC

Wakefield, Mass.

Russia is introducing a new regime of oil export duties that is changing the type of products refiners produce and export to global markets. These reforms, which are prompting refiners to upgrade their plants to produce cleaner products, will reduce margins to their lowest levels in years for many Russian refiners opting not to add to their processing complexity (OGJ Online, Jan. 24, 2014).

The profitability of Russian refining under the new oil export duty regime will trigger a wave of Russian 10-ppm ultralow-sulfur diesel (ULSD) exports and will enable Russia to outcompete most other foreign suppliers to Europe, according to a recent study by ESAI Energy LLC. As a result, Russia will expand its market share in Europe at the expense of European refiners as well as competing foreign suppliers.

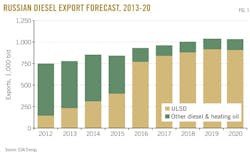

ESAI Energy forecasts Russian exports of 10-ppm diesel will skyrocket to more than 900,000 b/d in 2020 (Fig. 1), with large volumes of 10-ppm exports to strengthen the link between Russian diesel and Rotterdam 10-ppm diesel prices. New Russian supply combined with the availability of clean diesel from other suppliers outside Europe will prevent the price spread of Rotterdam 10-ppm diesel to Brent from recovering to the averages of $17-$20/bbl/year that occurred during 2011-13.

Refining profitability

Oil export netback price—the international price less the export duty—is the basis of Russian refining profitability. Until now, Russia's oil export duty regime discouraged upgrading fuel oil into clean products such as diesel. Under various structures over the last decade, export duties on products have ranged 40-90% of the crude export duty.

Until early 2011, the fuel oil export duty was equal to 40% of the crude oil export duty. In 2010-11, the small duty on fuel oil relative to crude increased the export netback price of fuel oil vs. pricing for Urals.

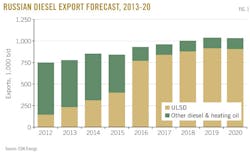

While high-sulfur fuel oil was priced at a $9/bbl discount to Urals in the Mediterranean, in Russia, the export netback price of high-sulfur fuel oil was $12/bbl higher than the Urals export netback price (Fig. 2). Essentially, the low export duty on fuel oil was a boon to simple refineries in Russia.

The fuel oil yield of a Russian refinery equipped only with a crude distillation unit is typically 40-50%, with some of Russia's biggest refineries fitting into this category. The profits on fuel oil underpinned high refining margins for these plants.

Fig. 2 shows the gross refining margin of a Russian simple refinery producing 44% fuel oil, with naphtha and middle distillates accounting for the remaining output. These margins exceeded $15/bbl in 2010-11, creating profits that discouraged refiners from installing deep conversion. Refiners with vacuum units were in no rush to add units to process vacuum gas oil into clean products. This combination of expanding crude distillation capacity and lack of upgrading capacity caused refinery yields of diesel to fall.

Despite a dramatic expansion of refinery throughputs, Russian refineries do not produce much more diesel today than they did a decade ago. Marginal increases in throughputs have resulted from:

• Existing refineries maximizing utilization rates and sometimes making incremental increases to capacity.

• Construction of new simple refineries that are not very big, but as a group, contributed considerably to throughput growth.

• Two key refinery expansions, both of which are still under way. These include the 2011 commissioning of Tatneft's Taneco refinery in Kazan, Tatarstan (OGJ Online, Aug. 6, 2008), which has since reached a capacity of 160,000 b/d, and a 2012 project designed to more than double distillation capacity at Rosneft's Tuapse refinery to 240,000 b/d (OGJ Online, June 25, 2013).

By 2013, Russian refinery throughputs increased 1.7 million b/d from 2003, but the average diesel yield fell 2.3% to less than 27%. As a result, refiners produced 1.47 million b/d of diesel in 2013, only 365,000 b/d more from a decade earlier.

But with reforms to export duties now imminent, Russia's government is about to upend things in a way that shifts refiners' priority to middle distillate output.

Tax reforms

The objective of Russia's old export duty regime was to make simple refineries profitable so they could generate the revenue necessary to invest in deep conversion.

Over the past few years, however, the government became frustrated with the slow pace of refinery modernization. To increase pressure on oil companies to accelerate investment, the government decided to set the fuel oil export duty equal to the crude export duty beginning in 2015.

The transition to a higher export duty began in late 2011, when Russia increased the fuel oil export duty to 66% of the duty on crude. But simple refineries' gross refining margins remained relatively high during 2012-13.

While the government planned to raise the rate to 75% in 2014, a resolution passed over the New Year holiday left the rate unchanged at 66%. The same resolution, however, confirmed plans to raise the rate of the fuel oil duty to 100% of the crude duty in 2015.

Fig. 2 shows the impact of this change on the fuel oil discount to Urals in Russia and the gross refining margin of a simple refinery.

Given a gross refining margin that shrinks to zero, refining expenses, and the costs of transporting product to export markets, it is clear that Russian refineries that do not upgrade fuel oil into clean products will no longer be viable. ESAI Energy projections show refining profits will not disappear, however; they will simply shift to the middle of the barrel.

Unlike the duty on fuel oil, the government is lowering the duty on diesel. During 2013-16, the rate at which this duty is set against the crude duty will fall to 61% from 66%. The small decrease of the diesel export duty will preserve the profitability of diesel.

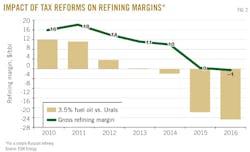

The difference between the export netback prices of ULSD and Urals was $36/bbl in 2013 (Fig. 3). While ESAI Energy forecasts weaker ULSD spreads to Urals in Europe, ULSD export netback prices relative to Urals are projected by ESAI Energy to remain at about the same $36/bbl spread.

Under the new oil tax reform, the export duty for gasoline will be kept at 90% of the export duty for crude oil, making gasoline less profitable for Russian refiners than ULSD. The government has no plans to change the gasoline export duty through 2016.

The shift of profits from the bottom to the middle of the barrel resulting from the impending changes to Russia's oil export duties is substantial when viewed in the context of the incentive to upgrade fuel oil into diesel.

The difference between the export netback prices of diesel and fuel oil will be $55/bbl or more after the increase of the fuel oil export duty to parity with crude (Fig. 3). By comparison, the difference between ULSD and high-sulfur fuel oil prices in Europe over the last few years has been about $32/bbl, according to data collected by ESAI Energy.

Planned upgrades

In anticipation of this transfer of refining profits to the middle of the barrel, ESAI Energy's analysis of 32 Russian refineries that account for 95% of Russian capacity indicates refiners are racing to add hydrocrackers and other upgrading units to process fuel oil into middle distillate and other clean products.

Surgutneftegaz's Kirishi refinery and Tatneft's Taneco refinery in Nizhnekamsk are commissioning 56,000-b/d hydrocrackers at each plant in first-quarter 2014. But these projects are just the tip of the iceberg.

The biggest expansion in overall hydrocracking capacity will take place from 2014 through 2016, during which period nine of Russia's refineries will commission hydrocrackers. TAIF Group's 7 million tonnes/year Nizhnekamsk refinery will add a 77,000-b/d hydrocracker in early 2016 (OGJ Online, Feb. 11, 2014).

Lukoil plans to complete a number of projects in 2015-16, including the commissioning of a 67,000-b/d hydrocracker at its Volgograd refinery (OGJ Online, Feb. 19, 2013), which alongside a dedicated ULSD export pipeline being built from Volgograd to the Black Sea, will lead development of ULSD exports to the Mediterranean. Smaller projects by Rosneft and other operators also are planned for start-up by 2016.

But some refining investments will not be completed until after the planned tax changes, including work at Rosneft's Tuapse refinery. While crude distillation capacity at the plant increased in 2013, the refinery still lacks the secondary units it will need to be profitable under the new tax regime. Currently, Rosneft only plans to commission secondary units, which will include an 86,000 b/d hydrocracker, in 2017.

Other refiners, however, are waiting for the Russian government to follow through with implementing the tax changes before making these expensive investments. While ESAI Energy forecasts some smaller independent refineries will close, a handful of them will add upgrading units.

According to ESAI Energy's review of Russia's refining industry, hydrocracking capacity will rise by more than 700,000 b/d between 2013 and 2020, with the ratio of hydrocracking and catalytic cracking capacity to crude distillation to expand to 25% from about 10%. Increased coking capacity also will contribute to a more complex Russian refining sector.

In addition to climbing diesel output, however, Russian investments in hydrocracking and other refining expansions have implications for product quality as well. Given changing domestic fuel quality requirements and Europe's use of 10-ppm diesel for road transport, producing cleaner transport fuels has become a high priority for both the government and refiners.

Between 2013 and 2016, Russia will cut the sulfur cap on diesel used for domestic road transport to 10 ppm from 1,000 ppm.

Given the need to produce cleaner fuel for both the domestic and European markets, more than 300,000 b/d of new diesel hydrotreating will be added in Russia during 2013-20. Recent and current investment projects at eight of Russia's refineries range from rebuilding and replacing older units to adding hydrogen capacity.

While upgrades to existing units account for more than 300,000 b/d of capacity, altogether improvements and additions of new capacity effectively add up to more than 600,000 b/d of diesel hydrotreating capacity.

Expanding infrastructure

This wave of investment projects means clean-diesel supply will outpace domestic demand, causing ULSD exports to soar. Two planned pipeline projects by Transnefteproduct, in particular, will support rising diesel exports.

Expansion of the Sever (North) product pipeline would make Northwest Europe the primary market for this diesel. Built in 2008 with a capacity of 170,000 b/d to facilitate ULSD exports from the Baltic Sea, the pipeline already operates above the nominal capacity. In late 2013, average diesel exports were 200,000 b/d, which rose to a record 235,000 b/d in January 2014.

Given rapidly growing demand, there are short-term plans to increase Sever's capacity by 80,000 b/d by expanding two sections of the pipeline. These expansions would support exports from Bashneft's three refineries in Ufa, Gazprom's Salavat refinery, GazpromNeft's Omsk refinery, Lukoil's Perm refinery, and the Antipino refinery in Tyumen, as well as link other ports to the pipeline.

By 2016, the Sever pipeline should be able to transport about 300,000 b/d of diesel, roughly 100,000 b/d more than the volume transported during second-half 2013. Given growing export volumes, Transnefteproduct could pursue a third phase of expansion, boosting the pipeline's capacity to 500,000 b/d.

The first leg of the Yug (South) pipeline to the Black Sea will also be built, but ESAI Energy projects ULSD exports from the Black Sea will develop more slowly and be limited.

Transnefteproduct initially planned the Yug pipeline in 2008 as the Black Sea counterpart to Sever, with hopes to begin construction in 2011. At the time, planned capacity was 180,000 b/d. If fully implemented, the 1,500-km pipeline will run Syzran-Saratov-Volgograd-Novorossiysk and link to 10 refineries. The Volgograd-Novorossiysk section, the first leg of the pipeline to be built, could be completed in 2016 or soon afterwards. Lukoil's Volgograd refinery, which already produces 10-ppm diesel, is ready to commit product to the pipeline.

ESAI Energy considers it unlikely that any additional legs of Yug will be built before 2020.

Global competition

The consequences of Russian ULSD exports are far-reaching. Until now, quality issues limited Russian market share in Europe.

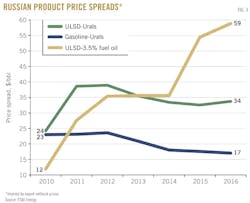

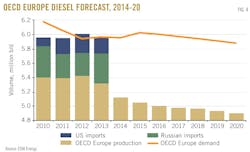

In recent years, Russia exported about 750,000 b/d of diesel to markets outside the former Soviet Union. But OECD Europe absorbs only a little more than one half, roughly 400,000 b/d, of Russia's exports (Fig. 4). Exports of clean diesel will enable Russian exporters increasingly to penetrate Europe's road transport fuel market.

Increased Russian supply to Northwest Europe puts Russia on a collision course with US Gulf Coast refiners. Latin America is the primary export market for US exports, but refining investment in Latin America eventually will enable that market to cut diesel imports. When that happens, US Gulf Coast refiners will seek to compensate by exporting more diesel to Europe, where they will meet stiff competition from Russia.

Similar to Northwest Europe, Russian ULSD exports to Mediterranean destinations pose a competitive threat to clean-diesel exporters from East of Suez markets. Russian deliveries to Europe also have implications for long-haul tanker transport.

More generally, Russia is contributing to a mismatch of supply and demand. Globally, there is much new and planned refining capacity oriented towards diesel production. There has been, however, a slowdown of diesel demand growth in many key countries, including but not limited to China and India. Developments in Russia will worsen the glut.

The author

Andrew Reed ([email protected]) is a principal of ESAI Energy LLC and has been with the company for 7 years. A specialist in Russian and Caspian energy with experience living and working in the regions, Reed speaks fluent Russian. He heads ESAI Energy's coverage of the Russian/Caspian region and middle distillate market, serving as editor for Global Fuels Outlook, a monthly outlook on petroleum product markets. He holds an MA (2000) in international economics and Russian studies from John Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.