CLARIFYING GOM DECOM COSTS-1: Settled-liability data provide insight for cost estimates

Mark J. Kaiser

Center for Energy Studies

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge

Cost data in the oil and gas industry are proprietary and obtaining them is difficult. Unless collected across a large and diverse sample, summary statistics are unlikely to be representative of the activity or process these data are trying to specify.

This article applies settled-liability data to imply private information on the cost of decommissioning in the Gulf of Mexico. Decommissioning activities are important to several stakeholders in the region-including the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) and Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)-that regulate the sector, the operators that hold liability for their assets, and the service companies that provide labor, equipment, and vessels to the market.

In 2002, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued requirements that companies account for their long-lived assets in the period acquired.1

Companies record the fair value of a liability for an asset-retirement obligation (ARO) when there is a legal obligation associated with retirement of a tangible fixed asset and the liability can be reasonably estimated.

This first of a two-part series describes the disclosure requirements of asset retirement obligations. Settled liabilities and adjusted settled liabilities are identified, and their application in decommissioning cost estimation outlined. A description of the methodology concludes the discussion. The second part next month describes model results and a new market index.

Disclosure requirements

US oil and gas companies have a legal obligation to plug, abandon, and dismantle wells and facilities they have acquired and constructed.2 The legal obligation to perform asset-retirement is unconditional, but uncertainty may exist about the magnitude, timing, and method of settlement.

AROs are those for which there is a legal obligation to settle under existing or enacted law, statute, written or oral contract. Uncertainty about the timing and method of settlement is factored into the measurement of the liability when sufficient information reasonably exists to estimate fair value.

For many oil and gas companies, most asset retirement costs consist of well abandonment and structure-decommissioning costs for their offshore properties, even if most of their wells or production are onshore.

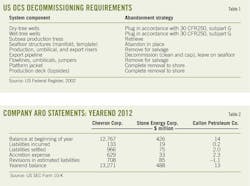

Offshore well abandonment costs are at least one or two orders of magnitude higher than onshore well abandonments for which there is no comparable activity for structure removals and subsea infrastructure (Table 1). The objective of decommissioning is to return the site to its predevelopment conditions.

Offshore decommissioning is much more expensive than onshore due to logistical issues associated with working in water at various depths and in difficult weather, and the need for specialized heavy-lift vessels. Diving requirements and additional regulatory scrutiny add to the cost of the operation.

For unconventional operations, cost differences are amplified, since hurricane-related activities often cost between two to five times normal operations and, in exceptional cases, may exceed conventional costs by ten times or more.

Asset-retirement costs are capitalized as part of the carrying amount of the long-lived asset. The amount of decommissioning liabilities recorded is reduced by amounts allocable to joint-interest owners, anticipated insurance recoveries, and any contractual amount to be paid by the previous owner of the property when the liabilities are settled.

Companies are required to disclose the beginning and ending aggregate carrying amount of AROs showing separately the changes attributable to:

1. Liabilities incurred in the current period.

2. Liabilities settled in the current period.

3. Accretion expense.

4. Revisions in estimated cash flows.

ARO: beginning of year

ARO liability reflects the estimated present value of the total amount of future well abandonment, dismantlement, removal, site reclamation, and similar activities associated with the company. AROs represent consolidated values across all of a company's subsidiaries for all properties worldwide.

Companies estimate the ultimate productive life of individual properties and utilize current retirement costs, a credit-adjusted discount rate, and an inflation factor to estimate the expected cash outflows for retirement obligations.

Liabilities incurred

Liabilities incurred during the period relate to AROs from new wells drilled and infrastructure installed, property acquisitions, and increased working interest in leases with infrastructure. The cash outflow necessary to extinguish decommissioning liability occurs at the end of each property's productive life.

The amount and timing of these cash outflows is based on expected costs, as well as the timing of oil and gas production, and the depletion of reserves. All estimates are uncertain and subject to change due to changing cost estimates, commodity prices, regulatory requirements, revisions of reserves estimates, and other factors.

Liabilities incurred are recorded at fair value and represent an estimate based on current conditions and technologies related to the expected timing of the obligation. Some companies break out liabilities incurred from construction separately from increased working interest or property acquisitions in which the liabilities are sometimes referred to as "assumed liabilities."

A liability for an ARO may be incurred over more than one reporting period if the events that create the obligation occur over more than one reporting period (e.g., multiyear drilling campaign, deepwater development).

Liabilities settled

Settled liabilities represent the total cost of all decommissioning performed during the reporting period of a company and all its subsidiaries for all properties worldwide, as well as any liabilities associated with property sales, prorata to its working interests.

Some companies report settled liabilities from decommissioning separate from settled liabilities from property dispositions. This is a useful distinction since property dispositions may be large and are not directly related to decommissioning performed during the period. If a company had no property divestments or working interest reductions during the period, then settled liability represents total decommissioning expenditures during the period.

Adjusted settled liabilities account for reductions in liability due to property sales and reduced working interest and represent a proxy for decommissioning expenditures.

Adjusted settled liability

Liabilities settled during year t, LSt, are represented by the sum of decommissioning expenditures DECt, liabilities associated with sales transactions SALESt, and reduced working interest positions WIt (Equation 1 in accompanying box).

Settled liabilities denote the total cost of all onshore and offshore decommissioning performed during the reporting period prorata to a company's working interest. Adjusted settled liability LSt* isolates the decommissioning expenditures during the year by adjusting for liabilities through sales and reductions in working interest (Equation 2).

Property sales and reduction in working interest represent estimates of the present value of the cost to perform future retirement obligations.

Accretion expense

Accretion expense measures changes due to the passage of time in the carrying amount of the ARO liability. As a special type of interest expense, accretion expense is computed at the company's credit-adjusted risk-free rate multiplied by the amount of the ARO liability at the beginning of the reporting period.

Revisions in estimated liabilities

Inherent in all present-value calculations are numerous assumptions and judgments regarding the estimation procedures and the parameters employed in the assessment, including the magnitude and timing of the retirement obligations, inflation factors, discount rates, and changes in the regulatory, environmental and political environments.

All these factors overlap and occur simultaneously, and to the extent revisions to these assumptions affect the present value of the ARO liability, a corresponding adjustment is made in the property balance. Revisions can be positive or negative and are estimated quantities based on the model assumptions.

Some companies break out the change due to discount rates, foreign exchange rates, divestments, etc., but many companies do not and only report a consolidated revision.

ARO: yearend

AROs represent stock at a point in time, whereas all the other terms represent flows between the reporting dates.

If AROs are compared to a bath tub in which water is fed by incurred liabilities and accretion expense and drained by liabilities settled through decommissioning, property divestments, and reduced working interests, then the level of water represents the ARO at a point in time adjusted for revisions (Fig. 1).

Formally, the end-of-year ARO liability is determined from the ARO liability at the beginning of the year plus liabilities incurred and accretion expense, minus liabilities settled and the change in revisions, which may be positive or negative (Equation 3).

In Equation 3, AROt = asset retirement obligations at the beginning of year t, LIt = liabilities incurred in year t, LSt = liabilities settled in year t, AEt = accretion expense in year t, and REVt = revisions in estimated liabilities in year t. This is referred to as the ARO accounting or balance equation.

ARO and settled liability examples

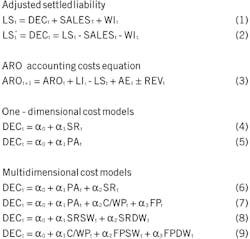

Chevron Corp. is an international and integrated oil and gas company with offshore operations across several basins worldwide, including Alaska, Brazil, Canada, China, North Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, North Sea, Southeast Asia, and West Africa. At the beginning of 2012, Chevron reported $12.8 billion in AROs worldwide and settled $966 million in liabilities during the year (Table 2).

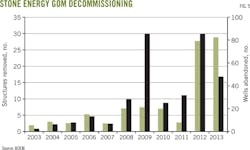

Stone Energy Corp., an independent that operates primarily in the Gulf of Mexico, reported $426 million in AROs and settled $75 million in liabilities in 2012, $68 million identified with decommissioning activity (Fig. 2).

Callon Petroleum Co., a small independent with operations onshore and in the Gulf of Mexico, reported $14 million ARO liability at the end of 2012 and settled $1 million in liability during the year.

Activity correlation

AROs and settled liabilities change over time depending on the company's purchase and sales agreements, development projects, decommissioning activity, market conditions, and other factors (Figs. 3 and 4). In 2012, Chevron settled about 7% of its AROs, $966 million on a $12.8 billion balance, whereas Stone Energy settled nearly 20% of its $426 million retirement obligation.

For companies with operations primarily in the gulf, such as Stone Energy, decommissioning expenditures are almost entirely related to their offshore activity (Fig. 5). For international companies, settled liabilities refer to all decommissioning activity performed worldwide, and because international companies combine activity from many different basins, companies with global operations cannot easily be used to extract regional data.

Exogenous events, changing regulations

Normally, property acquisitions and new construction are the main factors increasing ARO, and decommissioning activity and sales are the primary factors decreasing ARO, but the impact of exogenous events and changing regulations can also be significant.

In 2005 and 2008, for example, hurricanes in the gulf caused major damage to infrastructure, which increased AROs of companies affected, in several cases by several hundred million dollars or more, and subsequently led to increased decommissioning spending in the region.

In 2010, the federal government issued the "Idle Iron Guidance," which accelerated the time frame associated with decommissioning nonproducing structures.3 This requirement causes liabilities to be incurred earlier and results in a higher present value of ARO liability.

One-dimensional cost models

The simplest models relate decommissioning cost with the number of structures removed SRt or the number of wells abandoned PAt per year (Equations 4 and 5). One-variable models need to be interpreted carefully, however, since reported cost is all-inclusive, and dumping decommissioning cost into one variable makes it easy to misinterpret the unit cost as representative of the activity being performed, while in fact it is an upper bound on activity cost.

Multidimensional cost models

Decommissioning cost are determined by several different activities, of course, and by enlarging the number of variables and accounting for the spectrum of work tasks that occur, multidimensional models provide more detailed and useful cost statistics provided that the sample sizes are adequate to delineate activity categories.

Structures removed may be described by type as caissons/well protectors, C/WPt, and fixed platforms, FPt, and classified by water depth. Fixed platforms and structures in water less than 200 ft deep are denoted by FPSWt and SRSWt. Fixed platforms and structures in water deeper than 200 ft are denoted by FPDWt and SRDWt.

Many different formulations are possible with these variables (Equations 6, 7, 8, and 9), and provide insight into operational activities. The best representation is strictly an empirical issue. For these models, the coefficients "ai" are interpreted as the average cost to perform the operation described by the variable over the period and aggregation selected.

Model expectations

All model coefficients-except possibly the intercept terms-are expected to be positive because decommissioning cost is positively associated with activity, and as activity increases costs should increase.

In Equations 4 and 5, we expect a1 > 0. In Equation 6, we expect 0 < a1 < a2. In Equation 7, we expect 0 < a1< a2 < a3, since the average cost to plug a well is less than the average cost to remove a structure and the average cost to remove a caisson or well protector should be more than well abandonment but less than platform removal, for all other things equal.

In Equation 8, we expect 0 < a1 < a2 because the cost to decommission structures in deepwater will be more, for all other things equal, than structures in shallow water. Similarly, in Equation 9, we expect 0 < a1 < a2 < a3.

References

1. "Statement of Financial Accounting Standards Accounting for Asset Retirement Obligations," Financial Accounting Standards Board No. 143, Norwalk, Conn., 2001.

2. "Oil and Gas and Sulfur Operations in the Outer Continental Shelf: Decommissioning Activities," Department of Interior, Minerals Management Service, Herndon, Va., Federal Register 67(96), 35398-35412, 2002.

3. "NTL No. 2010-G05: Decommissioning Guidance for Wells and Platforms," Effective Date: Oct. 15, 2010, Expiration date: Oct. 14, 2013, US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf Region.

The author

Mark J. Kaiser ([email protected]) is professor and director, research and development division, at the Center for Energy Studies at Louisiana State University. His primary research interests are related to cost, fiscal, and regulatory studies in the oil and gas industry. Kaiser holds BS, MS, and PhD degrees in engineering from Purdue University.