Pipeline, CNG top Cyprus gas export options

Ali Pourbozorgi

APR Co.

North Cyprus

Tahir Celik

Cyprus International University

North Cyprus

Pipeline and CNG are the best options for exporting natural gas production from Cyprus to relatively close markets in terms of both initial cost and probable benefits. LNG, meanwhile, would only be cost-effective if exported to higher priced Asian markets.

Preliminary exploration drilling indicates estimated natural gas reserves in Block 13 of the Aphrodite basin of 3.1 tcf.1 Aphrodite basin is adjacent to the estimated 122-tcf Levant basin (Fig. 1).2 The other 12 Aphrodite blocks inside Cyprus's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) require further exploration but offer the potential of still more reserve growth.

Reserve size will play an important role in determining the type and amount of investment made both upstream and downstream to optimize gas resources. Evaluating alternatives to develop the 3.1 tcf currently on hand, however, should be occurring now.

This article will evaluate four midstream alternatives for bringing Cypriot gas to market with life-cycle cost benefit analysis (LCCBA). The alternatives evaluated are:

• CNG.

• LNG.

• Pipeline (to Turkey via Cyprus).

• Gas-to-wire (GtW), electricity.

Assumptions, criteria

LCCBA considered the following assumptions:

• Life cycle from start of construction, 20 years.

• Discount rate, 12% nominal.

• Interest rate, 7% (commercial lending rate).

• Inflation, 2.59%.

• Distances to markets; CNG, 2,000 km (about 1,100 nautical miles); LNG, 6,000 km (UK, Belgium); 7,500 km (China, Korea).

• Loan payback period, 12 years (principal and interest).

• Wellhead price, $3.50/MMbtu.

• Price at destination; Europe $11.98/MMbtu, Asia $16.53/MMbtu.

• Natural gas price increase, 2%/year.

• Plant efficiency ratio, fuel loss; 92% and 8%, respectively.

CNG

CNG is pipeline-quality natural gas compressed to 15-25 MPa (2,000-3,600 psi) or chilled to -40° C. and compressed at lower pressures. No operational bulk CNG transport project has been commissioned. One major obstacle is the weight of CNG vessels. A typical 140,000-cu m LNG carrier has a dry weight of about 35,000 tons, while a CNG vessel of similar capacity would weigh more than 200,000 tons. CNG vessels would therefore carry smaller volumes.

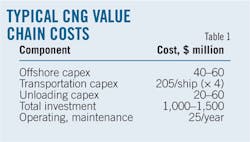

Table 1 shows a cost breakdown for CNG supply proposed by the Centre for Marine CNG Inc. Table 2 shows CNG's life cycle costs and benefits.3-6 These results pertain to exporting natural gas in the form of CNG to other Mediterranean countries within a haul distance of 2,000 km.

Life-cycle costs include inflation, discount rate, and annual natural gas price increases. For a 20-year study life, the first 3 years will be dedicated to construction of the plant, vessels, and any other relevant operations. Net present value (NPV) is $4.03 billion and internal rate of return (IRR) 81.49%

LNG

LNG is pipeline-quality natural gas that is condensed into liquid by reducing its temperature to -161° C. (-256° F.) at atmospheric pressure. An LNG value chain is a capital-intensive investment. Ernst & Young estimates a newly sanctioned LNG liquefaction plant would cost $2,600/million tonnes/year (tpy) capacity, compared with historical prices of $1,200/million tpy.7 Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank suggested in the same report the the estimated new-build price for North American and East African LNG projects would be less than $2,000/million tpy and Australian LNG projects more than $3,000/million tpy.

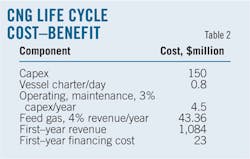

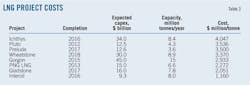

A single liquefaction train's capacity for an economic LNG plant typically is 4-4.5 million tpy, equivalent to at least 195 bcf/year or 534 MMcfd of natural gas and therefore roughly 4.5 tcf of reserves to operate for 20 years.8 Inter Oil published information regarding ongoing projects and their costs in September 2012 (Table 3).9 Vessel charter rates in early 2014 were roughly $70,000/day.10

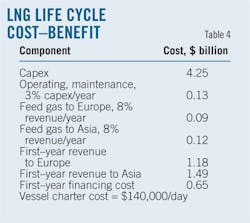

Table 4 shows the costs and benefits calculated for shipping LNG to either Europe or Asia. These results and the data from Table 2 yield LNG's NPV and IRR (Table 5).

Pipeline to Turkey

Pipelines to transport natural gas from Cyprus to European markets could follow one of two routes: through Turkey or through Crete to Greece. The latter option would require complex subsea engineering and has an estimated cost of $5 billion.6 This article will concentrate instead on the more straightforward pipeline to Turkey.

A pipeline to Turkey via Cyprus would include three segments (Fig. 3):11

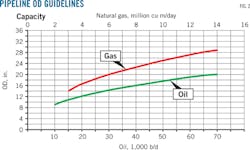

• Segment 1: from the wellhead to Cyprus landfall (currently agreed for Vassilikos), a ~130 km offshore pipeline at an average depth of 1,700 m with an assumed 28-in. OD.

• Segment 2: from Vassilikos to Kyrenia, ~75 km of onshore pipeline without complicating topography and an assumed 40-in. OD.

• Segment 3: from Kyrenia to Turkey, a ~90 km offshore pipeline at a maximum depth of roughly 1,300 m with an assumed 24-in. OD.

The pipeline's initial capacity would be 420 MMcfd, an estimated 120 MMcfd of which would be for domestic consumption in Cyprus. The 120 MMcfd is based on displacement of an estimated 25% (60,000 b/d) of Cyprus's oil imports2 and the country's expected population growth over 20 years. The amount is consistent with the last tender for natural gas supplies, 0.9 billion cu m (bcm)/year12 (roughly 87 MMcfd), and a 35% increase in the Turkish Cypriot population. Combined these two factors would require about 118 MMcfd of gas, excluding any industry conversion from other fuels to natural gas.

Estimated capital expenditure (capex) for the three segments of the pipeline combined is $1.27 billion, with operating and maintenance costs estimated at 5% of this. NPV is $5.21 billion and IRR 53%. NPV at 12% discount rate (weighted average cost of capital) and the IRR assume initial capital was provided by a third party and the only project obligation is to pay back the loan within 12 years.

Gas-to-wire

Natural gas could be converted to electricity at a power plant in Cyprus, with the electricity exported to Europe on the 2,000-Mw Eurasia interconnector. The export price of electricity in the EU from the European Commission website based on average wholesale electricity prices in Europe13 is €55/Mw. CO2 pollution allowances are not included in these calculations.

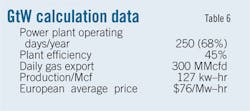

1 MMbtu of natural gas produces 127 kw-hr based on 45% plant efficiency.14 Efficiency typically measures 40-60%15-17 and operating hours 6,000/year.18

Table 6 shows the raw input data for production calculations of a 1-Gw plant. Capital cost is an estimated €650/kw and operating costs 3% of capital,19 yielding €650 million and €19.5 million, respectively.

Comparison

A pipeline to Turkey has the highest NPV, $5.2 billion. This option's limited flexibility, however, at least partially undermines its financial benefits.

CNG had a $4.03-billion NPV. Although uncertainties surround the technology, this option offers good flexibility of supply and delivery within a geographic range suited to currently available reserves.

LNG to Asian markets is the option with the third best NPV, $3.5 billion, supported by higher natural gas prices in Asia. This choice's NPV would be higher-high enough to move it ahead of CNG-if the number of vessels estimated to be available, 2.3, had been used as estimated instead of rounded down to 2. LNG projects, however, remain capital intensive and typically require a minimum reserve base of 4-4.5 tcf.

The fourth option is LNG to Europe with a $2.1-billion NPV. The lower value stems from a combination of lower volumes and lower prices to Europe compared with Asia. This option would strengthen ties between Cyprus and Europe but would not maximize Cyprus's profit.

The final option is GtW at $1.8 billion NPV. This option would maintain Cypriot control of its natural gas, but the Eurasia Interconnector's uncertain costs and growing use in Europe of electricity from renewable sources would pose ongoing threats. The option would also increase Cyprus's CO2 emissions without delivering a high rate of return

References

1. Hazou, E., "Noble Exploring Floating LNG Option," Cyprus Mail, Jan. 3, 2014.

2. US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Country Analysis Note: Cyprus, 2014.

3. Economides, M.,Wang, X., and Marongiu Porcu, M. "The Economics of Compressed Natural Gas Sea Transport," SPE Russian Oil and Gas Technical Conference and Exhibition, Moscow, Oct. 28-30, 2008.

4. Economides, M., and Mokhatab, S.,"Compressed Natural Gas: Monetizing Stranded Gas," Energy Tribune, Oct. 18, 2007.

5. Center for Marine CNG Inc., "Marine CNG Viability of Supply," presentation to Canada's National Energy Board, Apr. 25, 2006.

6. Paltsev, S., O'Sullivan, F., Lee, N., Agarwal, A., Li, M., Li, X., and Fylaktos, N., "Natural Gas Monetization Pathways for Cyprus: Interim Report - Economics of Project Development Options," MIT Energy Initiative, Oct. 21, 2013.

7. Ernst & Young, "Global LNG: Will New Demand and New Supply Mean New Pricing?", March 2013.

8. Durr, C., Coyle, D., Hill, D., and Smith, S., "LNG Technology for the Commercially Minded," Gastech, Bilbao, Mar. 14-17, 2005.

9. Visaggio, C., "Economics and Financing of Integrated Gulf LNG Project," InterOil, September 2012.

10. Saul, J., and Vukmanovic, O., "Ship glut burdens LNG tanker markets, slashes profits," Reuters, Mar. 11, 2014.

11. University of Zagreb, "Assessing Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Value Chains," (course), 2012.

12. Hazou, E., "Emergency meeting' called on interim gas," Cyprus Mail, Dec. 24, 2013.

13. Eurostat, "Energy price statistics," European Comission, accessed Mar. 20, 2014.

14. EIA, "How much coal, natural gas, or petroleum is used to generate a kilowatthour of electricity?," June 13, 2014.

15. Tweed, K., "Siemens Claims World's Most Efficient Gas Turbine," greentechmedia, Nov. 16, 2011.

16. Nyberg, M., "Thermal Efficiency of Gas-Fired Generation in California, 2012 Update," California Energy Commission, March 2013.

17. Salvadore, M.S., and Keppler, J.H., "Projected Costs of Generating Electricity: 2010 Edition," Paris Dauphine University, July 2010.

18. VGB PowerTech eV, "Investment and Operation Cost Figures-Generation Portfolio," August 2012.

The authors

Ali Pourbozorgi ([email protected]) is an engineer in North Cyprus for the Tehran-based Arian Pasargrad Rad (APR) Co. He was previously managing director at APR in charge of energy efficient building methods and before that commercial director of Saman Petrochemicals. Pourbozorgi holds a BS (2013) in civil engineering from Eastern Mediterranean University, Cyprus, and an MS (2014) in engineering business management from University of Warwick, UK.

Tahir Celik ([email protected]) is professor and dean of engineering faculty at Cyprus International University, North Cyprus. He previously founded the construction engineering and management program in civil engineering at Eastern Mediterranean University. Celik earned a BS (1978) in civil engineering from Middle East Technical University, Ankara. He holds both an MS (1985) and PhD (1989) in civil enginnering from Loughborough University, UK. Celik's research interests include quality management, life cycle costing, and construction methods.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com